Before the 21st century and the invention of the streaming service, you would probably have first come across Dead Can Dance in any number of contexts, from chill-out rooms to Hollywood soundtracks for films like King Arthur and Gladiator. Although originally living in Australia in the early 1980s, Dead Can Dance were consistently drawn to a dark European folk sound because of a strong emotional connection that they felt to the words and emotions conveyed by both voice and music.

Both core members, Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry bring different elements to the picture as songwriters. The former’s vocals push the band out of a conventional setup and into more experimental folk areas, with her vocals reaching out, where Perry’s style becomes more of an atmospheric staging for this.

New age music is seeing a bit of a reappraisal in recent years – perhaps because the internet has become the main context of listening, stripping the genre of its previous associations and presenting it differently. It’s hard to imagine many groups as idiosyncratic and spiritually orientated as Dead Can Dance growing and emerging in the 21st century though, with perhaps some exceptions including the Tibetan music influenced Phurpa and Aisha Devi.

Dead Can Dance too are a band fascinated by multiple strands of spiritual tradition, alongside ancient and medieval European history. It’s quite a heady, complex task bringing all of these inspirations together in a respectful or meaningful way under the banner of one music project, but the band were not looking nostalgically back to certain time periods, instead viewing music as a universal language or poetry that crossed time and culture – it was the emotional quality of music generally which drew Dead Can Dance towards it.

‘Dawn Of The Iconoclast’ from Within The Realm Of The Dying Sun (1987)

Gerrard’s far reaching voice would become the central theme of The Future Sound Of London’s single ‘Papua New Guinea’, where it’s used throughout as a sample. The fact that she used her voice more as an instrument than for communicating discernible lyrics meant that this would work as a hook that would become instantly recognisable. About ‘Dawn Of The Iconoclast’, The Future Sound Of London’s Garry Cobain told Sound On Sound that he found the song indirectly through his girlfriend’s ex-partner: “My girlfriend had gone and been unfaithful to me in Greece because I’d been unfaithful to her in Balham [South London]. She was teaching English and she did it with a student, and once she’d paid me back for my unfaithfulness — it was a one-all draw — we got back together, but she continued to receive these rather puppy-doggish tapes of tracks that were lamenting his lost love. Well, on one of them was the Dead Can Dance song. I’d always loved Dead Can Dance but I didn’t have that particular album, so I sampled it from the cassette."

Frontier from Dead Can Dance (1984)

In 1981, the non-professional, improvisation-focussed nature of Dead Can Dance’s music community in Melbourne meant that the musical project were free to explore a range of ideas that would eventually set them entirely loose from a traditional rock band setup. By the time they moved to England in 1982, their drummer Peter Ulrich said in a 2005 interview that both Gerrard and Perry had both come to writing music in very idiosyncratic ways: “Brendan had learnt to play guitar amongst the Maori community in New Zealand before playing bass and singing with a punk band there, while Lisa had – pretty much by chance I think – discovered and adopted the yang ch’in and piano accordion as her instruments, both of which she played in an untutored and unconventional manner.” The ability to fully explore these unusual musical inclinations would emerge gradually over time, however. Their track ‘Frontier’ shows some evidence that the band were keen on trimming back on some of their more free-form tendencies, where they tried to shorten the track to make it sound more concise – it originally started off as a long improvisation piece fashioned out of banging kerosene cans and a chair leg. Though it’s crucial to note that they didn’t have the backing of a label and so probably had to rely on really basic ‘found’ instruments in order to become less traditional at this point. Still, this is a crucial moment in the band’s development, immediately defining them as musicians with far bigger motives that they’re perhaps slightly reluctant to fully explore.

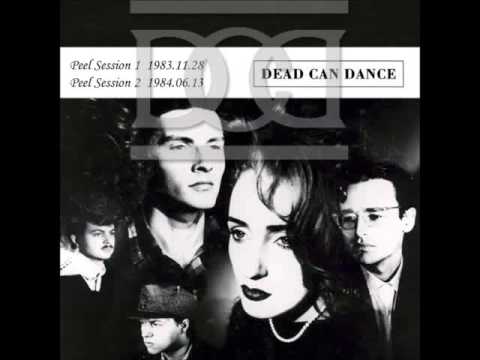

John Peel Sessions (1983)

Around the time of these Sessions, Dead Can Dance were exhibiting a kind of rough, scrappy Joy Division-esque appeal rather than the more minimal, restrained orchestral sound that would eventually come to define their subsequent output. A year before, the band had just moved to London from Australia, and the band would be defined mainly by the sound of Gerrard and Perry’s songwriting, so these recordings mark an early development for Dead Can Dance, just before the release of their self-titled debut and around the time of their EP, The Garden Of Arcane Delights. Here it’s difficult to deny an influence from British alternative music at the time; although not sounding exactly like Siouxsie And The Banshees, the image that they were cultivating wasn’t too far off. Gerrard’s operatic voice seems to be trying to break free from the constraints of it all, however, as alongside the rumble of percussion seems to take over each track with much force.

‘Flowers Of The Sea’ from Garden Of The Arcane Delights (1984)

Dead Can Dance were never at any stage concerned with being a conventional rock band, but on ‘Flowers Of The Sea’ it’s Gerrard’s voice that is helping to push their music in a more unusual direction, mainly due to the fact that the looseness of her voice helped to loosen up the structures of the songs. The rest of the band are just starting to explore other forms of instrumentation, but it’s still situated alongside some guitar and bass lines that wouldn’t stick out on an album by The Cure or Siouxsie and the Banshees.

‘Ascension’ from Spleen And Ideal (1985)

Following their debut, Dead Can Dance signed a publishing deal which enabled Perry to purchase a drum machine and a sampler, leading to huge advances in the way that the band were able to produce and arrange their second album, Spleen And Ideal, which takes on board a range of influences that include medieval and classical music. So with these in mind, it’s surprising to find that Dead Can Dance will time and time again insist that they rely mostly on intuition to build a song. When you listen to ‘Ascension’ from their second album Spleen And Ideal, this comment sounds like an understatement; few bands could take this course and pull it off with little more than a shrug of, “That’s just what we felt like doing at the time.” It’s also an album that sounds intensely spiritual, with ‘Ascension’ perhaps having some subdued, autumnal quality to it in the horn section that has the same minimal stateliness of These New Puritans’ Field Of Reeds. In order to write their songs at this point, the band started with the rhythm section first, writing the melody after that.

‘The Wind That Shakes The Barley’ from Toward The Within (1994)

As a result of an increasing interest in Ireland and its history, Gerrard covered ‘The Wind That Shakes The Barley’, a political song written in reply to the country’s 1798 rebellion, when an uprising against the British started in Wexford. The song originally found its way onto Into The Labyrinth, which for them was a time involving “telescoping into European folk history”, but the song would find itself in their live repertoire, featuring on their live album Toward The Within, during which the crowd remain respectfully silent. Gerrard said that she perceives the song’s mood to reflect more of an anti-war rather than rallying sentiment, because of its “intense sadness.” Perry would eventually relocate to Ireland by 1989, meaning that his working relationship with Gerrard became long distance.

‘Yulunga (Spirit Dance)’ from Into The Labyrinth (1993)

Unlike most of their music, this song has more of a foreboding than a melancholy atmosphere to it, thanks to its string section. The song’s title means ‘spirit dance’ in the Gamilaraay language of the Kamilaroi, the indigenous people of Australia. The language itself is now almost lost, rarely spoken except for a handful of people in what is now known as New South Wales in south-east Australia. Gerrard was living back in Australia during the making of Into The Labyrinth, but would visit Perry’s studio Quivvy Church in Ireland for recording sessions. Because of their separation, the album demonstrates an unusual coming together of influences that the duo shared with each other, with their lyrics at this point also drawing from Ancient Greek theatre and Bertolt Brecht’s poem ‘Die Ballade von den Prominenten’.

‘Orbis de Ignis’ from The Serpent’s Egg (1988)

On ‘Orbis de Ignis’ you haven’t just got a strong vocal performance from Gerrard, but Perry as well – both voices chime well together as part of this plainsong chant influenced piece. It’s almost completely an a cappella performance, except for the clanging of a bell during its pauses. Gerrard and Perry recorded this album at the same time as a soundtrack to the science fiction film El Niño de la Luna in Spain, as well as in London. Like the rest of The Serpent’s Egg, ‘Orbis de Ignis’ has a stately, reserved quality to it, and Gerrard is reining in her vocals more for these performances than on some of her earlier songs.

‘The Protagonist’ from the unreleased Music For Films

Dead Can Dance would work on a number of soundtracks, with a collaboration with their label 4AD being one of their earliest, although it seems that this never saw an official release. The band wanted to be involved with the filming process, but 4AD insisted that they would only be involved with its musical direction. The film would involve a ten minute long piece called ‘The Protagonist’, and an improvisational piece that Gerrard wrote before Dead Can Dance. ‘The Protagonist’ would be released on the 4ad compilation ‘Lonely is an Eyesore’, and it’s not clear what became of 4AD’s original film, although there’s an expressionistic music video that accompanies ‘The Protagonist’ on the live video on a compilation released by 4AD, Dead Can Dance – 1981 – 1998.

Song Of Sophia – The Serpent’s Egg (1988)

In the very early days of Dead Can Dance such as on their debut, Gerrard’s voice was strong, but it often sounded as if she wasn’t entirely in control of it. Once she arrived at ‘Song Of Sophia’, however, singing a capella style wouldn’t prove much of a problem to her, in fact her voice is so distinctive that it perhaps suits a lack of instrumentation around it. It’s easy to take her for granted as just being another talented 4AD vocalist, but her voice is actually quite different to that of label-mate Elizabeth Fraser. Gerrard’s vocals do reach out as Fraser’s often does, but can be more restrained, with a distance to it that can make it sound as if it’s emitting from a different room or building to the one you’re listening in.