Welcome back to Moviedrone, where we mercilessly dissect the latest film music releases and along the way try to show some actual appreciation as well as critical thinking.

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

With time creeping ever closer to the big four-zero for me, I’m more than aware of how long things are – be them records, movies, or relationships – and this certainly applies to soundtracks. Of course there’s no rule on how long and short soundtrack albums should run, and the production process has obviously changed greatly due to technology. But I get the sense that perhaps something has been lost somewhere – the art of arranging perhaps.

Curating is the word everyone uses now and perhaps that’s the best term to take to heart. The thing is, we’re a long way from the days of fifteen minutes a side, and maybe this is part of a larger debate about the album as a whole and its place in the digital music realm. There’s been pieces previously about the “death of the album” and how consumers can pick or choose tracks independent of the greater context of the record, and perhaps the soundtrack is an even more fascinating case because it’s something that is explicitly composed for another medium, in this case a visual medium. The soundtrack as it exists is a secondary channel for composers to exhibit after being written and arranged to support the needs of the film it’s attached so, so it’s a case of looking at the soundtrack to see how the music is best served away from its primary function.

Record labels and film companies would go further in the days when the LP was king, with some scores fully re-recorded with an orchestra to provide a bespoke arrangement of the music, as well as using overseas musicians to potentially bypass expensive reuse fees. Scores such as Jaws were re-arranged and re-orchestrated by the composer so they could add segues for cues and make everything into a coherent listening experience. In those days, soundtrack albums often had cues appear out of film order instead of a slavish devotion to the chronology of the picture, making for a more interesting listen, especially when you’re a composer who has to arrange for a quarter of an hour of music at a time.

The thing is, we are fairly spoiled, being in an age where more and more reissues of albums – not just soundtracks – are coming out as deluxe editions. In the realm of movie scores, a lot of times this means the soundtrack being reissued in its complete form in chronological order, as in the film. This is often a wonderful thing, as usually these are scores that have just had shorter soundtrack albums for a number of years, so an expansion is nearly always a welcome gift. However, these perhaps feel less special and important when the initial soundtrack album runs the entire length of a CD, or even more (last year, the deluxe edition of Brian Tyler’s The Mummy score ran over two hours). There are of course exceptions and conditions; some film scores do demand a larger canvas as it were, with John Williams’ Star Wars scores a good example of soundtracks that do work as longer listens because of the thematic complexity they rely on, and even something like 2001: A Space Odyssey because of the sheer scale.

But this is certainly not the case for your average Junkie XL thriller score, or even the scratchy modern low-rent Penderecki that makes up a certain degree of today’s horror scoring landscape, and frankly it gets boring pretty quickly. It would be an interesting question to pose to composers themselves, although I briefly spoke to Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury on Twitter about it the other day. They both said they put the scores into film order and it works for them (indeed they produce great soundtracks). What do you think?

NEW SCORES

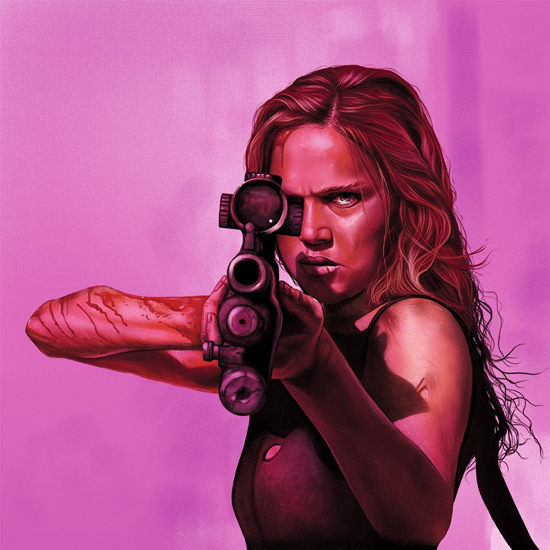

Rape-revenge thriller REVENGE (Death Waltz, out now) has been pulling in plaudits since its Cannes debut, and it comes with a shiny new electronic score from Robin Coudert aka Rob, who previously gave us a classic soundtrack with Maniac. Revenge has a starker aesthetic, less blood-drenched clubland; more desert survival, with a discomforting feel of desolation that’s hard to escape from. Although, to be fair, its opening track is, as they say, “a banger”. The score is genuinely frightening in places, especially one moment in ‘Rape Part 1’ where Rob seems to homage the tense ‘Laurie’s Theme’ from the original Halloween, and like Maniac it’s utterly essential.

COBRA KAI (Madison Gate Records, out now) is the name on many people’s lips right now, with the YouTube series being a hit and, to many, a surprising one considering it’s a sequel to a movie from 1984 (The Karate Kid). Composers Zach Robinson and Leo Birenberg embrace the synthesiser/orchestra combo favoured by original composer Bill Conti, albeit with a heavier concentration on electronics, and it’s a successful approach, mimicking the excess of the 1980s through synth colour but also grounding itself with instruments and rhythms that recall the more evocative qualities of the original score. There are some intense cues here that wouldn’t seem out of place in your workout playlist or the latest Street Fighter video game, but the best thing about Cobra Kai is that it still feels like its own thing.

In a similar vein, Rob Simonsen’s score to TULLY (Back Lot Music, out now) opens with the Velvet Underground and closes with a cover of Nancy Sinatra’s ‘You Only Live Twice’, but the brief and minimalist guitar-led score is still able to have influence, with an evocative dreaminess that contrasts with the songs throughout. That Bond cover is really fucking nice, too. Even better is LEAN ON PETE (Varèse Sarabande, out now), James Edward Barker’s score to a kind of 21st century indie War Horse. It’s not necessarily an easy listen but it has an ethereal streak that is hard to ignore, with the blurry emotional melodies hooking right into you. It feels like a horror score at times, and like the best horror finds profundity out of suffering. That’s a good thing.

Similarly disquieting at times is Patrick Jonsson’s score to DOG DAYS (Air-Edel, out now), a “social crime drama” that offers an insight into “the economnic and emotional struggles of China’s poor”. The score is understandably stark and tense with an ambient sensibility, a feel that we’re just moving through this, and there’s a battle between some of the melodies, where textures collide frequently. But there’s some gorgeous music here that really deserves to be appreciated.

Cult movie fans will be well aware of TENEBRAE (Waxwork, out now), the 1982 Dario Argento super-giallo that is once again scored by Goblin, only it’s not the full Goblin – members Claudio Simonetti, Massimo Morante, and Fabio Pignatelli are the ones here, with drummer Agostino Marangolo missing after the band disbanded. The trio produced what can only be described as a gothic prog odyssey, with the iconic Goblin funk breaks fully intact, and it’s presented on double-LP, with the original soundtrack program on one and tons of bonus tracks on the other. Goblin always felt like Pino Donaggio mixed with Rick Wakeman and their spongy synths have never sounded better on what is a beautiful pressing by Waxwork.

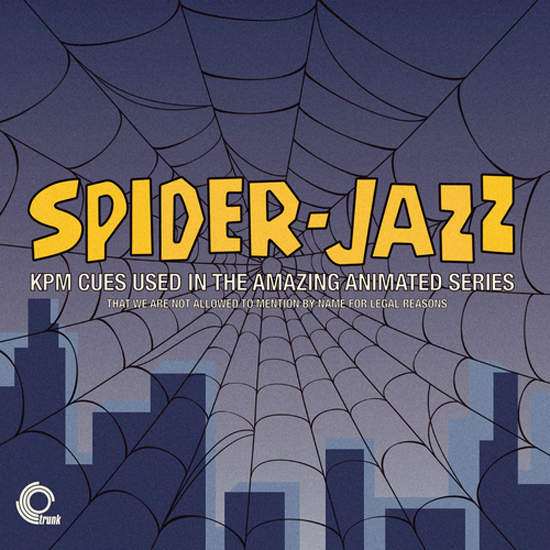

SPIDER-JAZZ (Trunk Records, out now) is maybe what you imagine it is, but I’ll expand by repeating the full title: “KPM Cues Used In The Amazing Animated Series That We Are Not Allowed To Mention By Name For Legal Reasons”. So what we have here is ostensibly the soundtrack to later seasons of a certain 1967 superhero cartoon made up of a bunch of amazing library cuts from composers such as Syd Dale, Johnny Hawksworth, Keith Mansfield, and others, and it’s just an incredible record. I was only able to get a digital copy so I can’t comment on the quality of the pressing, but Trunk’s rep speaks for itself. As for the music itself, you need to track this down, true believers – it’s magical.