This week it was announced that streaming platforms generated $7.1 billion in revenue in 2017, outstripping physical and other digital sales to become "music’s biggest money-maker". Cue articles like this, in The Guardian, which herald the dawn of a glorious new era of musical democracy, a world where bedroom artists and megastars alike are given equal access to a platform with the potential to make them huge, and a world where for the first time in a decade the people at the top have proper financial clout. Streaming, we are told, has apparently "saved the music industry".

It is an attractive prospect to believe that the longstanding wars of grossly unfair artist revenues that have long-dogged Spotify and its ilk are now resolved, but this is wishful thinking. The amounts of money made at the top might be steadily increasing, but this means nothing lest it trickle down, and for many artists on the exciting fringes of music, the kind we cover here at The Quietus, that isn’t happening. Take the artists signed to one of tQ’s favourite labels, Rocket Recordings, for example – home to Goat, Gnod and Josefin Ohrn. For them the idea of streaming platforms as salvation is “A load of bloody nonsense. Yes, streaming income is going up for us,” says founder Chris Reeder, “but it is a minute amount.”

The estimated amount of money that a single stream earns an artist on Spotify is $0.00397. Even though one listener might stream their favourite track hundreds of times, and a stream does not necessarily represent a missed sale, this is a pitiful sum. It requires new listeners to find the music in the first place, and millions upon millions of plays for this to translate to anything approaching a decent revenue. This can be done, of course, by arena-fillers like Ed Sheeran, but those not as popular in the mainstream must almost always bend to the will of the platform and become stream-friendly. “We are told we have to feed the ‘algorithms’ to help us be able make more pennies from it, which we are trying to do, but I can see it being a lot of hard work for very little reward,” continues Reeder.

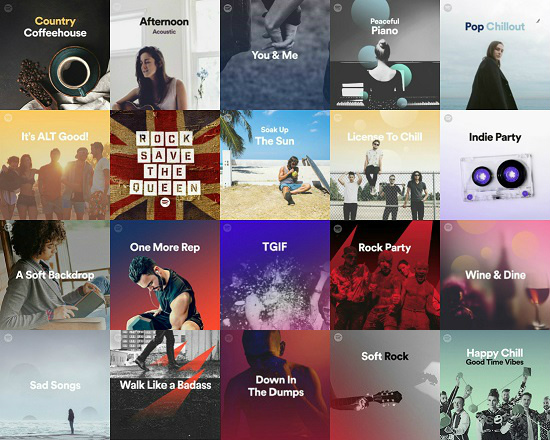

As The Guardian notes, the very nature of popular music is changing as a result of this pandering to fit the Spotify algorithm, getting rid of a long introduction from a song to make it less skippable, for example, or releasing alternate versions of tracks to appeal to curated playlists like ‘Perfect Concentration’ and ‘Peaceful Guitar’. But to submit to this system comes at the cost of artistic integrity. An alternate version of a track created entirely to earn a spot on ‘Infinite Acoustic’ in order to squeeze more streaming money might make commercial sense, but artistically this is pointless, empty and vapid in the extreme. Why should a musician have to compromise their work so drastically in order to make the money they need to survive?

Progressive music that goes against the aesthetics of whatever the mainstream might be at any given point by its very nature does not cater to the whims of a Spotify algorithm. Now that streaming is the industry’s biggest money-maker it has become the overriding force in music consumption. This dominance will only increase as time goes on, and for artists to gain anything as a result requires them to conform or die. There are exceptions, most notably in zeitgeist-seizing movements like grime that are both artistically essential and buoyed by the kind of mass appeal that in effect bypasses the need for a leg-up from the algorithms, but such a lethal combination is rare indeed. Not everything that is great is as popular.

With more money in the music industry, it is hoped this will naturally find its way back into recruiting new artists, but if high streaming figures and a spot on the ‘Walk Like A Badass’ playlist (562,000 followers) of generic rock stompers or the torturously soggy acoustic wash that is ‘Your Coffee Break’ (400,000 followers) are of primary concern, then up-and-coming artists who naturally cater to this will be of primary importance; major labels already have analytics expert to scout the unsigned talent that’s making the most impact within the algorithms. As Sahil Varma of the 37 Adventures label told The Guardian: “If you walked into any major label meeting this week, the thing they’d be talking about is how ‘Spotify-friendly’ an artist is. By that, they mean: can they get on Spotify’s playlists, such as New Pop Revolution or Chilled Pop?”

This is of course, to some extent, how major labels have always worked; they have naturally always signed the acts who are the most marketable. The difference now, however, is that they are not selling directly to the public, but to the streaming platforms and their algorithms in the hope that the product is smooth enough around the edges to fit neatly alongside others of the same type. Both the industry’s direction and the consumer’s tastes are being shaped by playlists that aim for uniformity and bluntness, meaning that music itself will become increasingly uniform and blunt. This is the cost of Spotify ‘saving’ the music industry, and it’s a dear one.

It feels unusual that there is a need to point out that artists should want to rail against homogeneity, but this is an era where if you want to be successful you must do precisely the opposite. For artists on small labels that once would have got by on a few thousand sales, there will be no great new influx of dearly needed cash to pay for equipment, studio time, mastering, manufacture and so on. Cosey Fanni Tutti, who as part of Throbbing Gristle, Chris & Cosey and Carter Tutti was able to make groundbreaking music in a time when underground records did sell, says that she feels that "a lot of musicians are in a ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ position. Access and accessibility

to music is crucial but creativity is being devalued by giving away the work as if it’s ‘disposable’ wallpaper." She adds that established artists like TG and Carter Tutti "have a small advantage. Through their fan base they can to some (lesser) extent mitigate the loss of revenue through some physical sales – vinyl mainly or by performing live gigs (if you’re fit enough and can get bookings). The younger musicians don’t have that. Just how do people expect new music to come through when the value of it’s vital place in our lives is reduced to a ‘giveaway’." And, of course, there is still one area in which people contribute far more than a tenner a month to listen to music on streaming services: "People seem happy to pay the big business players though – buying a device on which they can stream the music they pay nothing for," Cosey says.

Labels we speak to at tQ report selling only 10-20% of what they did before streaming, so where will the money come from to provide decent places to record, mastering, production and getting the music out there? The Spotify crumbs are never going to fill that gap. It might be easier than ever to get your music online, but for many artists it still costs a lot of money to make in the first place.

If streaming platforms keep growing more and more influence over how music is curated and marketed by those in charge, while the revenue for those not mundane enough to fit their algorithms remains so pitifully minute, it is not that impossible to envisage the blandest landscape the industry has ever seen. Great music will continue being made, of course, but getting that music out to people outside of the algorithms will be so much harder. “I hope I am wrong,” says Reeder. “I hope the revenue from streaming does improve, because if it doesn’t, well, who knows how positive the future will be for the majority of music makers and labels out there?”