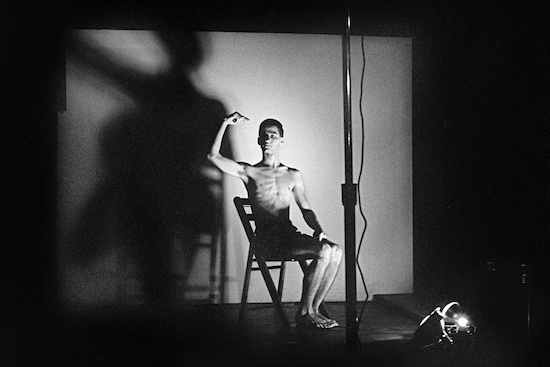

Acts of Live Art at Club 57. Pictured: Larry Ashton. 1980. Photo: Joesph Szkodzinski. Courtesy Joesph Szkodzinski

There’s something decidedly odd about staging a Club 57 exhibit in the basement of the Museum of Modern Art – akin to building a bonfire underneath an igloo. MoMA boasts annual revenues in the hundreds of millions, a two-Michelin Star restaurant and almost unlimited access to the world’s most decorated artists. Club 57, the eclectic, all-embracing performance venue that scorched its way onto the East Village scene from 1978 to 1983, couldn’t even afford a liquor license. Its most devoted patrons were struggling artistic types who sneered at the creative-industrial complex. Forty years later, their art – some of which was never intended to be viewed during the daytime – has made the long trek to midtown.

To be fair, Club 57 was always a fish out of water. Located in the basement of the Holy Cross Polish National Church on 57 St. Mark’s Place, the venue was the brainchild of Stanley Strychacki, an up-and-coming music manager at Irving Plaza a few blocks away. To help run his latest venture, which he called the East Village Student Club, Strychacki recruited a manager, Ann Magnuson, and a gaggle of artists that included Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, John Sex, Susan Hannaford, and Tom Scully, many of them gay and enrolled in Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts. Judging by his website, Strychacki sees himself as something of an unsung hero in New York’s nightlife history, overshadowed by his younger, more charismatic hirees. “On Wednesday, February 8, 1978,” he writes, as if he’s describing October 26 1917, ”four punk bands ‘stormed’ my East Village Student Club and changed its name to Club 57.”

The new name was an obvious dig at Studio 54, the ritzy discotheque that had opened its doors the previous year. Say aloud the names of these two legendary nightclubs, the Yin and Yang of late seventies New York, and you can start to understand what they stood for. “Studio,” with its long vowels and dactylic lilt, evokes luxury, velvet ropes, and the smug superiority of the late “Me” Decade. “Club” is a blunt little noise, a snort in the face of at all that sleek uptown bullshit. Club 57 appealed to punks and New Wavers and DJs because it always seemed to be against something. It welcomed anyone who despised, in Ann Magnuson’s telling, “disco, Diane von Fûrstenberg and The Waltons.”

What, exactly, were Magnuson and her colleagues pushing back against? What do a dance craze, an haute designer and a TV show about a Depression-era family have in common? Hard to say – a certain seriousness, maybe, a kind of self-importance that’s always in danger of curdling into arrogance. The typical East Village club-goer probably couldn’t have defined the attitude she was rebelling against, but she knew it when she saw it. Instead of manifestoes, Club 57 offered mounds of irony, satire, parody, camp, sometimes mocking the idea of a stable identity. Toward the beginning of the MoMA exhibit, you’ll find sardonic ads for the “Ladies Auxiliary first tri-annual slumber party,” complete with garish pink angels and a personality questionnaire (sample questions: “What was your last physical ailment?” “Would you rather be cool or groovy?” “What’s your favorite aphrodisiac?” “What do you think about facial hair?”).

Much of 57’s satire was targeted at the midcentury mores its patrons had grown up with and then fled: TV dinners, debutante balls, Perry Como, the Book of the Month Club, The Andy Griffith Show. After 1980, the club found a suitable nemesis in the persona of Ronald Reagan, the grandfatherly fifties square who refused to go away. “It’s a Reagan World!”, a 1980 photo-collage by Magnuson and Tseng Kwong Chi, features images of smiling suburban families saluting their new leader. Their dopey names and outfits seem to belittle the Reagan Coalition’s would-be utopia, the return to a normalcy that was never that great to begin with.

Collage was, in many ways, Club 57’s quintessential medium. In a collage, nothing is natural, nothing “belongs,” and by the same token everything is welcome as long as it can be cut out and glued in place. The club’s monthly calendars were among its most impressive artworks, featuring hundreds of tiny letters and pictures Magnuson painstakingly removed from postcards and newspapers. Some of 57’s performers read experimental poetry in the tradition of William S. Burroughs (whose cut-up technique was a kind of literary collage), while early DJs like Fab Five Freddy used the club to perfect the art of musical collage. Then there were the managers, scarcely one of whom was a native New Yorker: Magnuson was from West Virginia; Strychacki was from Poland; Haring was from Reading, Pennsylvania. Almost without exception, they’d been cut and pasted into the East Village.

Beneath all the layers of mockery at 57 lay an unlikely warmth that set the club apart from its Dada precursors. It’s there in the exhibit’s recreation of Kenny Scharf’s “cosmic cavern,” a lurid, blacklit funhouse packed with plants and blobs of clay. Passing through, you can begin to understand what it felt like to stumble onto the downtown avant-garde scene in 1978. You’re disoriented but not alienated; you don’t belong here, but neither does anyone else. The same buried sentimentality can be felt in the ads for 57’s Monster Movie Club, not a satire so much as a love letter to the gloriously cheesy black-and-white horror movies of yore; it’s easy to picture Magnuson snipping through old magazines late at night, driven by love for a nightclub that could barely afford to pay her.

Club 57 closed within a few years of the dawn of the AIDS era, and several of its stars went on to become key figures in ACT UP and NEA’s culture wars. As the stakes of resistance grew higher, their art got angrier and more incisive. Seen today, 57’s aesthetic seems gentler than what succeeded it, teasing the authority figures who’d only just begun to endanger innocent lives. (Compare, for instance, the depictions of Reagan in Magnuson’s 1980 photo-collages with those in ACT UP’s “AIDSGATE” series from 1987.)

Is Club 57 worth mourning? It served as the birthplace for some phenomenal art, to be sure, and its radical air seems especially relevant to the current moment. (Thirtysomething Trump was, needless to report, more of a Studio 54 guy.) But it also seems in keeping with the spirit of Magnuson, Scharf, Haring, et al. to question the nostalgia that underlies a milieu-recreating show like MoMA’s, even if the show was guest-curated by Magnuson herself. The shrewdest response may be to celebrate Club 57’s spirit of gleeful defiance while remembering Magnuson’s own words: “We did it for each other, and we enjoyed it, and then we were on to the next thing the next day.”

Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983 is at MoMA, New York,sta until 8 April 2018