As a Chicago native, Honey Dijon had the inside track to house music from a very early age. As a dancer first (like all DJs worthy of the mantle) she was not even 13 when she started going to the city’s primarily black and gay house clubs; using the age-old excuse of sleeping over at a friend’s house, plus a fake ID.

She discovered this underground scene through her friendship with Derrick Carter, her inspiration as a DJ, along with Mark Farina, another Chicago DJ who would become a lifelong friend. But it was her move to New York in the 90s that really pushed her towards her calling behind the decks. This was before “Giuliani Time” and Disney taking over the city, so NYC was still a worldwide centre of off-kilter music – house, techno and punk rock all flourished in a city that was still affordable, even if it wasn’t always safe. Here she met Danny Tenaglia, another DJ she still considers, like Carter, “truly brilliant. I mean so technically gifted that even I wonder, ‘How the fuck are you even doing that?’”

More recently, as house music began to re-evaluate its roots after the minimal techno era took a well-deserved backseat, artists like Dijon, who have the history of house music in their bones as well as their ass-shakingly good DJ sets, have ascended again. Her sets at Panorama Bar have, by her own admission, bought her career to another level. Now she’s more visible than ever before on club and festival line-ups worldwide, which is the reason for our chat. You may have seen her thing on the decks in Smirnoff’s We’re Open ad campaign to promote more understanding of non-binary identity in nightlife. She even remixed disco deity (and LGBT+ hero) Sylvester’s track ’Stars’ for it with vocals by Sam Sparro (an EP of which will be out for Record Store Day). But she will be much more involved in their new Equalising Music project.

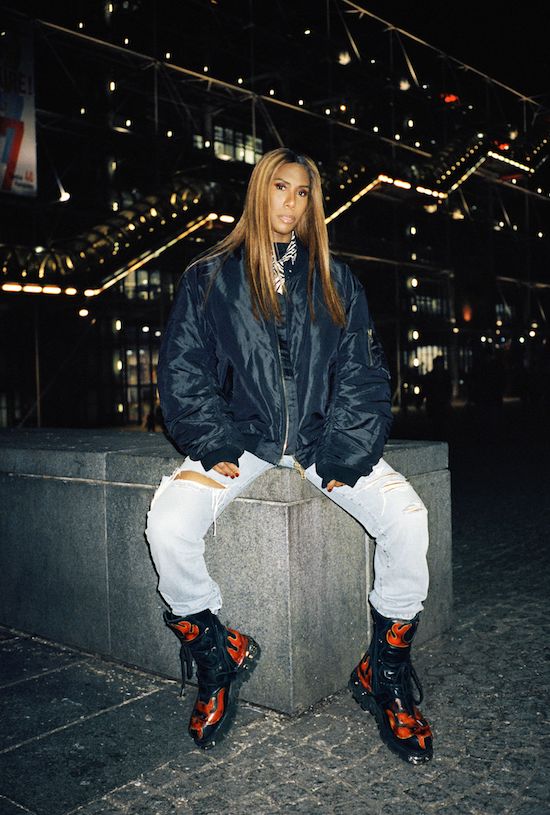

This project will select ten of the best female and non-binary DJs to be mentored by big-time talents like The Black Madonna, Nastia, Peggy Gou, Artwork and of course Dijon herself. They will then perform at either Snowbombing, Lost Village or at Printworks. Dijon is, of course, the perfect choice here: as a trans woman of colour who’s been involved in house music since its beginnings, the contradictions of the scene are her lived experiences. What started as the underground music of black and Latino LGBT+ kids is now more white and middle class than ever. But strong roots never go out of style and with equality now firmly on the agenda, tQ was more than happy to chat with one of electronic music’s most individual and outspoken characters.

So you’re playing at Battle Hymn tonight – Luke Solomon has mentioned that place to me before. Is it like the NYC of old? And can I ask you what it’s like to DJ and party in NYC in these post-Giuliani and Bloomberg days?

Honey Dijon: It is very much like New York was before gentrification, yes.

That must be quite a relief for you, as New York has been so important to you as a DJ – and personally too, of course?

HD: It absolutely is. New York is a very different place now than it was in the 90s and that is mainly because of gentrification; which you also see in all the big capital cities of the world, I mean London especially suffers from it too. But there are still good places to party – and to DJ – in New York if you know where to find them. And I do… [Laughs]

I’m sure you do. But if we can start off by going back to your own beginnings growing up in Chicago, I know your father was a huge Marvin Gaye fan in particular, so would you say that soul music – with its unifying, liberalising message – was the first driver for you musically?

HD: For me to properly answer that you have to understand the period that I was growing up in, the 1970s itself. After the craziness of the 60s culture died out with people like Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin dying, the 70s was more about sexual revolution. A good example of this is what we were just talking about, Marlon Brando hooking up with Marvin Gaye… and Richard Pryor too [as per the revelations in Quincy Jones’ memorable Vulture interview].

People were just freer then – sexually, emotionally, in every way. Marvin was spilling his heart on What’s Going On but what people forget is that Berry Gordy didn’t even want to release it! He just wanted Marvin to keep releasing all that smooth shit. But Marvin insisted and so he started that trend for singers baring it all; with people like Jodie Mitchell and Carol King coming later. But this was just a part of being an African American person growing up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1970s. As an African American person…. you know what? I’m just gonna say “black” [LAUGHS]. Being black and from Chicago, which is a very musical place – it had rock, soul, disco – music was constantly on in my house. It was a daily part of life for us. On Fridays we’d get pizza as a family and just dance around to the music we all loved. That was just normal. Music was a huge part of all our lives back then.

So that really set the tone for you as a music-lover? How about as a DJ?

HD: Oh, I was a ‘selector’ [LAUGHS] from the age of three, so I am told. I know it sounds a little crazy, but I swear my mother tells me I was obsessed with these little kiddie records you could get. They call it a damn ‘selector’ these days but I was really just fascinated, I wanted to play that music that everyone was dancing to – because my parents would have parties in our basement – and it just lead on from there.

How much was house music that unifying liberalising force in your own life, then? Like soul was for your parents and their generation?

HD: Well, it certainly was a force, but if you want to look at how it was a force, you have to understand disco first. And the person who introduced me to disco was Lora Branch. I was friends with her younger brother, which is how I met her. And Lora was the person who introduced me to disco; to Salsoul, to Prelude, to those kinds of labels. Because disco is what became house, so I discovered disco first, definitely. Lora was a black, queer DJ who was close to Frankie Knuckles from his days at The Warehouse [the seminal Chicago club from which ‘house’ music got its name, which was open from 1977 – 1987, though Knuckles left in 1982], so she’s someone who was really there at the beginnings of things for me.

I’ve heard you mention her in interviews before, but she’s not someone whose part in the early house scene is well-known at all.

HD: No, that’s certainly true. There are so many people and so many places, so many venues that don’t get a mention in the annals of history.

So can I ask you to mention some of them? As you say, it can’t have all been about the Warehouse and the Music Box?

HD: Oh, it definitely was not. Now, let me see… there was the Rialto Tap which was on the South Side, Club LaRay over on the North Side, the Bistro, there was Normady’s, a Latino gay bar we went to, there was AKA, the Windy City… These places all played amazing music and as they just blew my mind at that very young age.

So would you say that clubs have been a ‘safe space’ for you, to use a very fashionable term, as a Black trans woman?

HD: Yes, absolutely! These spaces are so needed because not everyone is straight, heteronormative and white! In NYC especially, where I was a drag artist – as many trans people are before they are ready to live fully as a trans person – they were places I could go to feel safe, to feel good as myself, but also to earn a living where I didn’t have to sell drugs. Or my body, for that matter.

Do you feel that they are still that way? Or can they be again?

HD: I feel like the tide is turning on that front. After nearly 40 years of house music culture there’s a feeling that we are going to again own our own spaces and feel safe in them. “Safe spaces” is exactly what this comes down to: for people to feel safe, to have a home. That idea also feeds into how I DJ. I play music vibrationally so people can feel good – I don’t care about playing some rare fucking tune so that three guys at the back can nod to themselves at how clever I am. That whole crate-digger persona thing just kills me – I am all about finding new records but I do not pontificate on it and I definitely don’t base my identity as an artist on it. If that’s the only way you can be interesting, well, then maybe you’re not very interesting!

I can only agree on that note. But if we’re talking about clubs as places of safety, do they need to be overtly political, in a time when they’re under threat?

HD: No, they don’t need to be. I just don’t think it’s necessary to do that.

Well then can I ask you how see yourself in a political sense? In terms of gender on trans issues? In these days of President Trump, are you party political?

HD: You know what? I’m just at a point in life where I look at everything subjectively. I just don’t do ‘group think’ on any level at all. If you’re looking for me to point at someone else and say, ‘That’s how I think about things’ then I’m sorry. Not going to happen. I’m sorry but I just can’t answer that any further.

That’s absolutely fine, no need to apologise. On to the reason we’re actually sitting down together, can I ask how did you get involved in Smirnoff’s We’re Open campaign in the first place?

HD: Well like all the best lovers they approached me first! [LAUGHS] No, well, I was asked to do it; it’s as simple as that. And anything I can do to make clubs more accessible, more equal and safer, I will do.

So what does non-binary identity mean to you? Because ‘We’re Open’ is about making clubs places non-binary people especially feel comfortable especially, right?

HD: Not either side, neither or. If binary means just zero or one, there’s a whole hell of a lot of in-between, even in physics there’s more in-between, so I think it’s just a matter of society trying to catch up with that complex reality of life as it is lived.

Ok, that’s actually a very concise definition, thank you. So what about hetronormativity on the dancefloor and socially homogenous clubbing crowds – how do we combat this?

HD: If I knew that I’d be a hell of a rich club owner right now, I’ll say that much. [LAUGHS] But overall I really feel that the internet separated everything: now everyone’s so locked into their own little niche. “I only like techno, I only like dubstep.” Now you even get people who like genres from one place, like, ‘I only like German techno.’ Believe me, I’ve seen it. People used to move around and be more open-minded because the boundaries weren’t so clearly defined. And every kind of person would go out to the clubs, gay, straight, whatever; back in the 80s and 90s when you had to go out in order to hear music, or get laid, or even to get work.

That’s how I ended up DJing for fashion brands; I just got to know the people from being out and from DJing. Gay clubs were known as forward thinking back in the day. That is not the case now, for the most part. There are some exceptions, like the Berghains in Berlin, the Chapter 10s in London, the Battle Hymns in NYC, but they are the exceptions. Mixing is what keeps it vibrant. Post Frankie Knuckles dying, I always think: how many Black, queer producers are there now? Not just making ballroom music, which takes a lot from house culture, but making house itself. I mean, with Derrick [Carter], myself, and K-Hand… there are so few names now. Why? I don’t know. Is the information not being passed down? Or is it the monotonous music that is being played? Just tracks with no vocals, no passion…

I agree with you about the music, to an extent, but I always think marketing is a part of the answer too. Most people of colour are as vulnerable to marketing as most white people, after all. I mean I remember being a teenager in the 90s and being part of what felt like the first generation of POC kids who had hip hop directly marketed to them as ‘their’ music.

HD: Honey, life is marketing.

Wow… that’s one of those worrying realities of life, isn’t it?

HD: Well, it is and it isn’t, if you understand that it doesn’t have to be. Everyone’s identity is marketed to them to some degree: how you should dress, the music you should like, what you should eat and drink and so on. But if you’re strong enough you can move away from it all; you can be that Chinese girl, who loves hip hop, who only fucks trans men! [LAUGHS]

I’ve really thought about this a lot, because as you know I work a lot in the fashion business, so it can be easy to fall into fashion rather than owning your own style. Now I feel that for me, when I stepped away from what was happening – and there was a long time I wasn’t working, what with electro and then minimal blowing up – and just looked to myself, a lot of things started happening for me. And I have to thank Berghain for that, they really took a risk on me and allowed me to just be me. I mean people said to me, “You cannot play vocals there!” But I knew that was bullshit because I played at Ostgut [the Berlin club’s late 90s / early 2000s predecessor] and anyway, I’m not scared of vocals when I play. They let me be me, anyway.

That just shows what a power they have these days.

HD: Oh, absolutely. How many other clubs have female queer residents? Not very many, I can tell you. Not on that level. It just doesn’t happen.

So as we’re talking about Berlin, where I know you’re based when you’re in Europe, I have to ask you about Berghain and its door policy?

HD: It’s there because it’s a gay club. That’s it; it’s there to protect what is inside a place that people take very seriously. It’s there to stop tourists, to stop gawkers, to stop people who are not going to participate. Over time it seems to have become about something else, but that’s what it means to me.

Ok, so to go from Berlin back to NYC again, I was looking on your very eclectic and inspiring Instagram and I saw an amazing picture by a NYC rock promoter, I think his name was Michael Alonzo? That one of the guy flexing his muscles?

HD: Oh, Michael Alago! Now a lot of people don’t get that this is the culture I’m from in NYC; punk rock as well as house. He was this gay Puerto Rican guy from New Utrecht Avenue in Brooklyn booking and managing all these bands –have you seen the Netflix documentary Who The Fuck Is That Guy? about him?

I haven’t, I’m afraid. I just saw you mention him and wanted to ask you about him, as I can see your Instagram is very much focused on people you find culturally interesting, from all the different worlds you inhabit – like fashion, clubs, art etc.

HD: Michael was a huge part of what made NYC vital in that period from the 70s onwards until I was living there in the 90s. It was crazy that this young kid could go from hanging out in these punk rock clubs to booking these huge acts. He signed Metallica, you know? That picture is one of his, he’s a photographer nowadays, but he was huge on the NYC band scene from the 80s until the early 2000s, I think.

I’ll definitely check it out. So as we’re talking about creativity and talent in a wider sense, you’ve said in the past that you’d like to mentor a young DJ. Now it seems that will now happen as part of the Equalising Music campaign. So can I ask you how important that protégé and mentor relationship is to you?

HD: Well, all I can say is that I think I’ve been lucky enough to have some amazing experiences and I am happy to be able to pass them on. I don’t think I’m some big expert, far from it. In fact I’ve fairly recently become friends with Bruce Forest who will tell me about how things were at Better Days [the 1972 – 1990 West Side NYC club where a young inexperienced Frankie Knuckles first started DJing, to cover for resident Tee Scott on the unpopular Monday and Tuesday night slots], so I’m still learning too. I’m just a conduit for my experiences unto the world. That might sound very grand, but it’s true.