Formed in 1977 by Marc Hollander and Vincent Kenis, the Belgian avant-rock band, Aksak Maboul,

excelled at the playful construction of ersatz yet exciting musical forms and counterfeit cross-cultural soundtracks that seem ever more radical and innovative with the passing of time.

Their first recording, Onze Danses Pour Combattre la Migraine (‘Eleven Dances for Fighting Migraines’), fused early electronica, classical chamber orchestral, improvised jazz, Balkan folk, traditional Turkish music and Satie-esque miniatures with a light and humorous touch that transcended its hybrid nature to anticipate future musical forms, such as its proto-techno opener ‘Saure Gurke.’

Often cited as a high-water mark recording of Rock In Opposition, the band’s second album, Un Peu de L’âme Des Bandits, also foresaw the fluidity of both genre and nationality later exemplified by Hollander’s Crammed Discs, as the label’s inaugural release. Henry Cow drummer and Recommended Records founder, Chris Cutler, who played on the record, recalled: “My abiding recollection of the recording itself is of a series of jaw-dropping moments when, one after another, my fellow band-members whipped out some ridiculous overdub or negotiated a series of hair-raising musical slaloms, as if retying a lace.”

A third phase, with vocalist Véronique Vincent, begun in 1980 but not finalised until 2014 with the release of Ex Futur, brought renewed interest in the band and a series of live dates across Europe – the first in 40 years. tQ spoke to Hollander via Skype.

As a long time fan of the record, it was pleasing to see Un Peu de L’âme Des Bandits, at the top of this site’s albums of the month feature. Why now for the reissue?

Marc Hollander: As you probably know, we reformed the band and played some live shows after the release of Ex-Futur in 2014. We played maybe 35 shows in six or seven countries, over three years. It was really exciting. Then in 2015 we reissued the first record, Onze Danses Pour Combattre la Migraine, and we’re currently working on a new album.

Marc Hollander live with Aksak Maboul in 1979

Ex Futur was recorded between 1980 and 1983, why did it take so long to be released?

MH: Originally it was supposed to be the third album but it turned out to be an electro pop version of Aksak Maboul. We thought it was too pop for part of the audience but too bizarre to be considered a pop record and we just left it. We thought we just needed to produce it better, and then four years ago, I started thinking actually these demos which looked so weird at the time, people could like that.

It anticipates bands like Stereolab and Broadcast to an uncanny extent.

MH: Exactly. That thing was obviously too early. Initially I thought let’s take the demos and see what we can do with them, perhaps just do a digital release. Then the more we worked on it, the more we saw people actually loving it. So we did a proper release and got amazing reactions, from media and audience. Then people started asking, are you going to do shows? I hadn’t been on the stage in 40 years, and for Véronique it was even worse. I at least had been involved in music, producing records and everything, but she had left the musical scene completely. But then the idea made its way in our brains and we thought ok, let’s do one small show with backing tapes and maybe bring in one, or possibly two musicians, and then suddenly we had a proper band that sounded really fat and groovy, which gave a different life to these tracks. So we started touring, which was a really unexpected and exciting experience.

How close is the new material to being finished, and what kind of thing can we expect?

MH: It’s far from being finished, because my main job takes time, but I’m slowly working at it. We have three or four songs, not recorded, but written. Stylistically, my dream would be to combine all three albums and roll them into one. It would be more like what we do live, more electronic, less song orientated, with elements from stuff that was on the other two albums. It’s an interesting challenge.

Bandits is often cited as a pinnacle recording of the Rock In Opposition movement. Can we talk about RIO for a bit?

MH: RIO became kind of a cult, a sect almost. Especially now, there are still fans, and it’s become like a genre of music, which is absurd in a way, because that wasn’t the idea. The idea was to gather like-minded bands, but not musically like-minded, people who worked outside of the mainstream and outside of rock and the Anglo Saxon domination by major companies. If you look at the original series of bands, some of them I didn’t actually quite like their music, but they certainly weren’t in what became known as the RIO style of music later on.

RIO in a way seems to be a bit of a niche genre, but records like Bandits and also Fred Frith’s Gravity, which you also worked on, deserve a much wider appreciation, I feel.

MH: It’s true, I think this album and Gravity, there’s more levity in these records. They are less heavy and serious, with some of the same musical elements. Also the sort of trans-cultural aspects, which were in Gravity were also Bandits. Fred Frith started recording that in between the two Bandits sessions. When you look at our album, on the label, I did all this silly/clever stuff, naming the tracks differently on the label and on the sleeve, and also named the band slightly differently. On the label, which has the working titles, all the songs have dance names, like tango, trio, or whatever, and its subtitle is ‘five dances’ – which is what Gravity is also. A lot of it’s inspired by different styles of folk music, but really twisting them in a personal way.

Chris Cutler called working with you on this record “both a pleasure and an education”. What was it like working with Cutler and Fred Frith, with you being such a Henry Cow fan?

MH: I sent them scores – there’s a bit reproduced in the booklet. All the music was basically written, except for the song that Fred wrote during the rehearsal sessions. We did two shows before the recording, and then another show at the RIO festival in Italy. Then after that, we recorded Art Bears and they asked me to play with them for the first (and last) Art Bears tour – which was quite an experience. It was quite tense, exciting, difficult. The music wasn’t easy, but it was great. Then the time came to mix the album and I wasn’t happy with the material, I thought something was missing. Then I came up with the ‘Modern Lesson’ track, which I wrote and demoed on my own. I thought it maybe needed something to wrap it up and maybe announce what would maybe come next, more drum machines again, harder guitars and stuff like that. I’m really happy that I did that, because it really sums up the record and opens up new doors. We included samples of every other song on the album. When I say samples, I mean grabbing the thing on an analogue tape and feeding it back in, because there were no samplers then. It was more like a musique concréte type of manipulation.

Who else would you cite as an influence, going back to your first two records?

MH: My influences are many, this is a function of growing up in Brussels in the 60s. It’s a fractured country, right on the border between northern Europe and the Anglo Saxon Germanic world and the Latin part of Europe, and it’s a strange place. There’s no strong Belgian culture. It’s an accident of history really that this became a country. It has a culture of course, but it’s always open to influences. It belonged to the Spanish and the Austrians, and the French, and maybe as a result of that, or maybe because of other things, there is no strong musical identity. People are just open to stuff that came from everywhere. So I constructed my own musical pantheon by picking up stuff from everywhere, borrowing records from a library, getting interested in music from Africa, the Balkans, Asia, jazz, free jazz and blues.

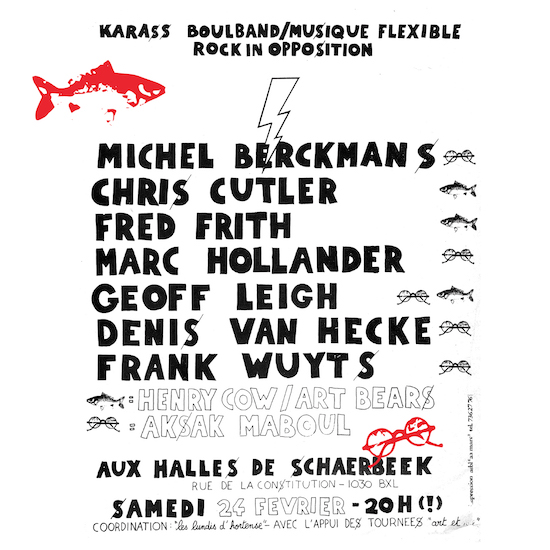

Aksak Maboul live featuring Fred Frith and Chris Cutler

What was your involvement with the Honeymoon Killers?

MH: With Aksak Maboul, I started alone, then I involved my friend Vincent Kenis, who later rediscovered Konono No1 and played a part in the creation of Kasai Allstars. Then we played shows with just four people, featuring material from the first album. We expanded gradually, bringing in more musicians for what I think of as phase two – like Michel Berkmans, the bassoon player from Univers Zero, Denis Van Hecke the cellist, and Geoff Leigh. Then when the time came to do the second album, Vincent had disappeared somewhere in Africa again and I needed a bass player, so I asked Fred Frith if he would come and play bass for us. I had met them through the first album, Chris really liked it and put it in his Recommended Records catalogue. Then when I met them again, I asked if they could both play on the record and they said ‘sure’, which was really exciting, as I was a fan of their band.

After that, I started getting fed up and I wanted to do something more ‘primitive’ – something rockier with these complicated superstructures on top. The Honeymoon Killers were a band from Brussels, who were pretty wild, ranging from free jazz, to brass band, to almost Beefheart sort of stuff. I asked three of them to join the next version of Aksak Maboul. At the same time, they asked me to join Honeymoon Killers, which I accepted. We did one show with just the three of them and Michel the bassoon player, and there are three excerpts from that show on the bonus disc that comes with Bandits. It’s almost like a direction which was never pursued, almost no wave. Then Vincent came back and rejoined the band and for a while we played under two names and tried to live this fiction that we were actually two bands and we were going to do two separate albums. What became Ex Futur was meant to be the Aksak album, but we recorded the Honeymoon Killers album, Les Tueurs de la Lune de Miel, because that was closer to being finished, and that took off immediately, which made us leave the other one to one side. We were pretty famous for ten minutes, including in the UK. We were even on the front cover of the NME.

How did all of these experiences help frame your mindset, when you started doing the label?

MH: At the time, I wasn’t thinking of doing a label, I just came up with the name because I needed a label name for the first Aksak album. Then gradually again, the idea made its way in my brain. I had started a small distribution, like a Recommended Records kind of thing. It was a fun period, sending stuff to musicians who were like-minded in the sense that they were trying to take control of the destiny of their albums. Then a lot of exciting stuff happened that was outside of the RIO sphere. Like, I was quite a fan of This Heat, Scritti Politi, other bands that were on Rough Trade. We started distributing a lot of that stuff around 78, 79. Then basically I wasn’t finding it easy to write music. I have a phobia of repeating myself, so I thought maybe I should do what we are doing with Aksak Maboul on a label level, which is to basically put musicians in touch, do experiments putting people together to record and work with music from all over the place. So basically, Crammed was an expansion of some of the ideas from Aksak Maboul. Looking at the bands, many of them have people from two countries that meet in a third country, and they dream of music of a fourth country, which they think that they are doing, and end up making music of a fifth country that doesn’t exist. That’s the definition of a lot of the bands that we work with.

How has the experience of running a label changed over recent years?

MH: In the past, you could put out a great record and people would just buy it, but now it’s getting harder to do just that. You tend to work more like an incubator for artists and take care of all the aspects of what they do. Try to find them agents, to make the whole thing work and also get income from all the various aspects because just putting out records is difficult. After the 80s, people thought we were an arty, post new wave label with a little bit of a RIO background, but it wasn’t true, because we put out things like Zazou Bikaye, which is totally electronic and African, but people want to pigeonhole you. Then the electronic thing came along and we put out records by 4Hero, Carl Craig, an artist called Juryman. We do a lot of bizarre drum & bass and at the same time we work with Taraf de Haidouks, Kocani Orkestar, Zap Mama. Then in the early 2000s, we started working with Brazilian artists. I like the fact that these things happen with an element of chance. We’re not looking for any one particular thing, things happen and you meet somebody who in turn introduces you to somebody else. This human factor, is valuable. We put out, I think 25 albums by Brazilian artists. It was a good moment to do it but I wouldn’t do it now. Because of that, we had the image of being a world music label, which is what happens as soon as you work with people who don’t sing in English or have strange names. We evolved out of that phase, as I’m so averse to being labelled like that.

Are there any current Crammed releases that you’re particularly excited about?

MH: I really like what we’ve done in the past few years. We’ve had artists like Juana Molina and Aquaserge. It’s a direction I have more affinity with as a musician. Juana Molina’s album is very good. It’s getting more and more complex and more exciting at the same time. We just signed an Anglo Nigerian artist call Ekiti Sound, who does electronic music with a lot of Nigerian influences in it. I’m also working with Matias Aguayo. He’s formed an electro rock band – keyboards, bass and drums. We put out the record a couple of months ago. It’s very 80s but also 70s and now of course. Aquaserge are part of this current wave of bands who are influenced by RIO and the good side of prog. Prog used to be a curse word in the 80s and quite rightly, because a lot of what is classified as prog is, for me, horrendous. For some strange reason, all this post Soft Machine stuff, or early Mothers of Invention, that I like, is also considered as prog. Aquaserge capture some of that spirit but in an original way. They also have elements of some experimental French bands of the 70s, like ZNR – Hector Zazou’s old band. I hope people with the Bandits reissue can see that the three Aksak albums are a continuum. I find that with younger fans, because we have a lot who discovered the band with Ex-Futur and went back to discover the other albums, they’re not so shocked by the differences between the records.

The whole thing of Aksak Maboul is that it keeps changing, because I’m like that, I get bored and need to move on. But there is a thread, even if the genres vary from one project to the other. I find that some people love the first album and find the second one difficult, or the opposite that people love the second one and think the first one is cute, and that the new one is pop or something, but for me I can see the thread. That was the purpose of the booklet. I found it interesting that Mikey Jones, who wrote the liner notes, articulated what I hoped some people would think; that it’s a gamut of different things, scandalously diverse and eclectic, but there is a thread running through it all. So is the label that I started on the footsteps of Aksak, and it was fun to see him elaborate on that.

The LP reissue of Un Peu de L’âme Des Bandits is out now on Crammed Discs and comes with rarities CD, Before And After Bandits (Documents 1977-1980, 2015)