Photo by PP Hartnett

In a modest council flat twelve storeys above East London lives a man whose influence on post punk music has been both profound and largely unrewarded.

"I think we were forerunners," Lawrence tells me, bringing a small wooden stool into a bare room that contains little more than a black modernist couch and a single Francois Hardy album, propped up against a turntable. "We were ahead of our time, and we could hardly get arrested then, with this type of music. We were trying to do a new kind of rock that was anti-macho and very dream-like. It was all about mystery and dream states, really."

Lawrence (surname long abandoned) is talking about his first and most revered band Felt, who fulfilled his master plan of making ten singles and ten albums in ten years (1980-89) before disbanding in the final days of the decade. Lawrence was matched in the first half of Felt’s career by prodigal guitarist Maurice Deebank, whose classically-inspired solos perfectly complemented Lawrence’s clean, melodic strumming and half-sung, melancholy vocals; an English Lou Reed or Tom Verlaine formed by the grey drizzle of 70s Birmingham rather than the cosmopolitan atmosphere of downtown New York. When Deebank left, keyboardist Martin Duffy (later of Primal Scream) took over, adding warm Hammond organ to Lawrence’s increasingly personal lyrics.

Throughout the nineties Lawrence fronted Denim, a self-styled cartoon band that laid down a blueprint for Britpop, only to be swept aside as that became a regressive campaign for "real music" at odds with Denim’s knowing celebration of pop’s artifice, tack and transcendent naffness. Railing against the idea of any received canon of worthy music, Denim drew on 70s glitter and novelty pop but sang about the Birmingham pub bombings and the whole confused mess of British popular culture that formed them. When they never achieved the fame that was the whole point of the exercise, Lawrence retreated to form "B-side band" Go-Kart Mozart. And although the current century has found Lawrence bedevilled by mental health problems, poverty and, for a while, homelessness (as movingly revealed in the 2011 documentary Lawrence Of Belgravia), Go-Kart Mozart have just released their fourth album, the brilliant Mozart’s Mini-Mart. Minimalist but brashly melodic electro-vaudeville jars jaggedly with raw, deadpan lyrics about depression, sexual dysfunction, living on £10 a day and watching filmed executions online. The vertiginous combination of the bleakly grim and the joyously hilarious makes it a perfect, meta-modern evocation of British life in early 2018. At the same time, this year sees Felt’s back catalogue being reissued, remastered and in some cases remixed under Lawrence’s personal supervision.

"It’s probably the last time this will happen, in my lifetime," he says. "It’s a chance to do it properly, how I imagined it in my mind. But before that it wasn’t as though I’d put them all in a vault and never listened to them for years. I listen to them for various reasons. Not for pleasure, but I might be doing a Go-Kart record and I might listen to a Felt record for a reference of some kind. So it wasn’t a shock when we started remastering and finding old tapes. When people say, gosh, you released that record 20 or 30 years ago it doesn’t seem like that to me at all. It’s like I released the Felt ones a few years ago, and now I’m doing new stuff."

LAWRENCE (1972-77)

Photo by PP Hartnett

Arguably the eccentric but strictly disciplined persona that Lawrence created for himself ranks as one of his greatest artistic achievements. It’s a project that began in his West Midlands childhood- an era he refers back to constantly in his songs. Profoundly affected by the otherness of glam rock stars like Bowie and Bolan, Lawrence saw seventies pop as an escape route from a working class childhood, in which he felt increasingly alienated from his peers. Leaving school at 15, he educated himself in art, literature, theatre and film, but it was always pop music that was the primary vehicle for his passion, imagination and ambition.

Lawrence: The first record that I ever bought, when I was 12, was ‘Starman’ which made a big impression. A lot of my generation had the same epiphany, seeing Bowie on Lift Off With Ayshea, and it changed everything for me. The way he looked, the short hair; the way he was. And then I really got into Marc Bolan and T-Rex, and then almost immediately Roxy Music came on the scene. I was a pop kid who wore high street clothes, but I was immediately drawn to what I thought was like a secret world. The first time I heard about The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed was through Bowie. And then I liked Cockney Rebel a lot, and then Be-Bop Deluxe, and then the punk thing happened.

I went to see T-Rex on my own when I was 13. I went on the Sunday morning and queued up in a massive queue all around the Odeon, and I got a ticket and I went on my own. And then I went to a few gigs, always at the Birmingham Odeon, because I could get in there. I saw Roxy Music, and then I saw Cockney Rebel and nothing until Iggy Pop, because David Bowie was playing keyboards. That was an amazing gig, March 1977, and The Vibrators were supporting, so that was the first punk band I saw. I thought yeah, this punk thing, that’s it for me now. Short fast songs.

Then the day I left school I went to see Television at the Odeon. All my friends were like, are you coming to the pub? No, I’m going to a gig. What? You’re not coming out with us, all your friends? We’re all going to the pub for the first time ever, we’ve left school! Why aren’t you coming? No, I’m going to a gig tonight. And they’d go, what are you doing that for? They just couldn’t understand it. That day was the end of any relationship I had with any of my old friends from school. It was quite an important moment, really.

Felt- ‘Index’ (single, 1979)

Photo by Jane Leonard

Felt’s first single, self-released by Lawrence before the band as such even existed, was completely uncharacteristic of their later work, or indeed of anything else. ‘Index’ is a slow-paced, unsteady two-chord thrash, with no bass or drums and inaudible, mumbled vocals. The B-side, ‘Break It’ is more of the same, only half as long. The most basic thing ever, it’s kind of brilliant in its audacity. Amazingly, ‘Index’ got made single of the week in Sounds, a year after it was released.

L: It was just me on electric guitar. I recorded it on a cassette player in my bedroom. I bought a £7 microphone from an electrical shop called Tandy’s, put it on a stand, played my guitar and pressed play. Whatever comes out, that’s the record: that was the idea. And then I’ll do something else, and that’ll be the B-side. And there was an advert in the back of Melody Maker, ‘make your own record’. All I had to do was send them a tape, and a record will come back. It was £500. It was an art statement. I worked in warehouses just to save up the money. It didn’t matter that I was going to lose the money. I wanted to make a statement, and I wanted to make it so radical that I would get noticed immediately, so I didn’t just want to write a song. I thought this is what I’m going to do: I’m going to make a crazy noise on the guitar.

It was reviewed by Jon Savage in Melody Maker but nothing happened, so I sent it off again to Dave McCullough who was The Fall champion and I said we’ve just released this record- I pretended- we’ve just released this record and we’re playing with The Fall. We’re quite different now but this is how we started. And yeah, he made it single of the week! It was just a dream. So that got Cherry Red interested. Mike Alway was an amazing A&R man, he’d taken over at Cherry Red, and eventually they signed us, and that’s how it started really.

Felt- Crumbling The Antiseptic Beauty (album, 1982)

Felt’s first two albums are cut from the same fine, fragile cloth: both Crumbling The Antiseptic Beauty and 1984’s The Splendour Of Fear feature six songs each and last approximately thirty minutes. Drummer Gary Ainge plays mostly toms- no cymbals or hi-hat- beneath Deebank’s Vini-Reilly-esque guitar figures. Half the pieces are instrumentals, while Lawrence mutters hazy beat poetry on the remainder, sounding forever separated from the world by a rain-smeared window. Listeners were divided: some found Felt’s brittle, brooding sound enticingly mysterious and fragile, while others thought them pretentious and unbearably twee. Unfortunately for the band John Peel, whose Radio 1 show was then virtually the only way for independent bands to get heard, was among the latter.

L: Maurice Deebank and me were at the same junior school but then we went to separate secondary schools. We saw each other all the time but I never spoke to him until he was 16. And one day this kid I knew said to me oh, you play guitar don’t you? I’ve got an album you’ve got to hear, it’s all guitars. He came round a couple of days later, and that day he happened to be with Maurice Deebank, so he came too. He knocked on my door and said I’ve got that record for you, and it was The Shadows. We went into my living room and I put it down, thinking I’m never going to play that, and Maurice Deebank picked up my guitar and he started tuning it, and in ten seconds he had it all tuned and he started strumming. And I was just, ‘Oh my god, this is incredible.’ He went, ‘It’s just three chords. It’s just ‘Mister Tambourine Man’.’ So I took a mental note of that. And then I made ‘Index’ and I thought this independent world is crap; I want to be in the charts. I’ve got to form a band: a proper band, along the lines of Television, with solos everywhere. I’m going to ask that guy because I know he can play guitar. So I asked him to join. He never really wanted to and I spent the next five years- he kept leaving and I kept going, ‘Please re-join, we can’t do it without you, I need you’, begging him. And he’d come back and then he’d go, ‘Oh, this is rubbish; I don’t want to do it.’ He just wasn’t into doing it. It took hours and hours to coax those solos from him. Tons of encouragement, saying, ‘You’re amazing, you’re a genius.’ He didn’t think he was any good at all.

The disaster of our band was that John Peel didn’t like us. And if John Peel didn’t like you, you couldn’t make a living. All of the bands that he liked were making a living from his show, because you’d do the session and then he’d play you every night, so your PRS was massive, and then people are buying the records because he’s playing them all the time. But John Peel was openly antagonistic towards us on air. He said once, ‘Here’s a band that’s getting loads of press at the moment. I don’t like them. It has the worst album title I’ve ever heard in my life: Crumbling The Antiseptic Beauty.’ And then he played one track. We were never a Peel band. We get asked to be on John Peel compilations, and I say he didn’t like us, he didn’t play us.

Felt- Primitive Painters (single, 1985)

The 1983 single ‘Penelope Tree’ felt like a breakthrough: a genuinely accessible pop single with obvious hooks and Lawrence’s singing clearly audible, but lack of radio support meant it never got the success it deserved. Felt’s third album, The Strange Idols Pattern And Other Stories (1984) was produced by John Leckie and featured classic Felt songs like ‘Sunlight Bathed The Golden Glow’ and ‘Whirlpool Vision Of Shame’ as well as a new clarity and sense of purpose. But it was a six-minute single taken from their fourth LP, Ignite The Seven Cannons, produced by The Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie, that was to be the closest they came to a hit. ‘Primitive Painters’ remains one of the enduring classics of the era, and Felt’s best-known song. Deebank’s chiming guitar filigree spirals magnificently atop the warm organ bed provided by new keyboard player Martin Duffy, while a sour-voiced Lawrence is countered by the soaring, angelic tones of Cocteau Liz Fraser to stunning effect.

L: After the second album I was desperate to be famous and get in the charts, so I thought right, I’m going to have to break my rule of not having pop songs on the albums. It was going to be pop singles but with strange long pieces on the album. So we mixed it all together, the pop songs and the other songs, just to try to get more attention, really."

John Peel had to play it, because his favourite singer was Liz Fraser, and it was number one in the indie charts. I think he played it maybe five or six times. It got to number seven in his Festive Fifty. That’s massive for a band he didn’t like or play.

How did you come to work with Robin Guthrie on that album and single?

L: Robin was a massive Felt fan and they got in touch with us and said we’re doing a tour of England, will you support us? That’s how it began and we became really great friends. But I wish he hadn’t produced it! He did a terrible production on it. He did one song that was really good, which was ‘Primitive Painters’. But that was because when we got back from Scotland where we’d recorded it we remixed it in a big London studio, because it was going to be a single. But on the rest of the album he just applied his Cocteau Twins techniques to Felt, which I didn’t want him to do at all. The mixing was three or four days at this residential Edinburgh studio, and I had to sign this piece of paper before he even got involved, saying I’ll produce the album for Felt as long as Lawrence doesn’t come to the mixing. And he mixed it and I never liked it, ever. You couldn’t hear the songs; it was just a load of effects and reverb. So I knew that one day I was definitely going to remix those six tracks, the ones with singing on them. And what I did was I took the master tapes home from Edinburgh at the end of that session. I stole them and I kept them with me for all of these years. And eventually the time was right. I actually went to [original Felt producer] John Rivers to remix them and said you’ve got to help me. Let’s do them like we would a Felt session, like we would with ‘Penelope Tree’ or whatever. We mustn’t use modern effects; we must do it as we would’ve back in the day. So yeah, we remixed the six tracks for the new version and I’m so happy with them, I love them.

We played ‘Primitive Painters’ to Robin in the studio, and he said straight away that should be a single. We went really? It’s six minutes long; that’s not a single. He said that’s a single, and he said to Liz, I’ve got a song I want you to sing on. Then a few days passed and once we recorded it she was upstairs in the bedroom, working on lyrics for The Cocteau Twins. He said come down; I want you to sing on this song now. I wrote the lyrics out for her on a piece of paper and she went into the studio and it was very spontaneous. She’s one of the best vocalists of the eighties; she had some spark of genius inside her. I think she did it twice and everybody agreed, straight away, yes, that’s it. There wasn’t any labouring over it or let’s come back tomorrow and take a few lines and redo it, it was: that’s it.

Felt- ‘Ballad Of The Band’ (single, 1986)

Photo by Mick Lloyd

Felt’s first release on Creation, ‘Ballad Of The Band’ was an obvious open letter to the departed Deebank.

L: Maurice had got married just before we went to Scotland. He took me to this café and he put his hand on the table and looked at me, and there was a ring. I went, ‘Oh my god, you’ve got married.’ And when he said in the van on the way back, ‘I’m leaving’, I just thought that’s it now. There’s no point in me going round and begging and all the stuff I used to do. This really had come to an end because he’d gotten married. I’d begun thinking that I’ve got to find a way to do this without him anyway, because it was too much stress. I was constantly worrying about when was he going to leave again, ‘What will I say this time that will drive him up the wall and make him leave?’ So I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve got Martin now anyway. I’ve met this genius and I’m getting into keyboards; maybe keyboards will get us in the charts because they’re softer and not so abrasive. Maybe that’s our new path.’ So I had Martin and I thought I can do this without Maurice now. But I didn’t want to, obviously.

Maurice was on ‘Ballad Of The Band’ when we used to practice that song, and he used to do an amazing guitar part on it, country style, it was beautiful. And I used to sing it in rehearsals, at him, and I thought he cares so little about this band that he doesn’t even know what I’m singing. That was one of the reasons why I did it, so that I could sing it at him, and see if he noticed. And he didn’t. It was only years later that he commented. He wrote in some online thing, ‘He even wrote a song about me once, saying how much he disliked me.’ But I didn’t hate him, I loved that guy. I was in love with him. I didn’t hate him. It was completely the opposite. But it was frustrating. I wanted to practice all the time. I wanted to do this, I wanted to do that, and he was very lacklustre about everything.

‘Ballad Of The Band’ was followed by another great single, ‘Rain Of Crystal Spires’, and one of Felt’s best-loved albums, Forever Breathes The Lonely Word. All have the thin wild mercury sound of 65-66 era Dylan, with Duffy’s Hammond organ right upfront in a dense and heady swirl of sound.

L: It was fortuitous because the studio that John Rivers used had an old Hammond. All we had was a stage copy, with no Leslie speakers, almost like a toy organ; there’s no power. And John Rivers used to be a keyboard player. He loved the Hammond anyway, so he knew how to get that great sound out of it. We were fortunate that it was there waiting for us in the studio, this great monster of an instrument. And Duffy’s so good; he just brought it to life.

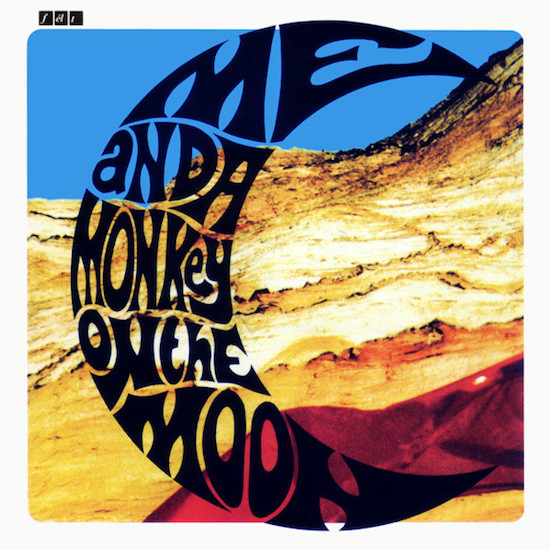

Felt – Me And A Monkey On The Moon (album, 1989)

Felt’s overlooked final album was a classic Creation record, with guests including Robert ‘Throb’ Young from Primal Scream on bass and Pete Astor from the Weather Prophets on backing vocals. Perversely it found the band back on Cherry Red, via Mike Alway’s él imprint.

L: We got a kind of, ‘Okay, we’ll pay you later’ deal with the studio, but when it came to getting the tapes, Alan [McGee] didn’t have any money again. He said, ‘I won’t have any money till January; we’ll do it in January.’ I said, ‘Are you mad? Don’t you get it? We’re finishing in December. It’s all over. We have to release this record.’ So I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to take it somewhere else.’ And he was fine with that. We were friends. So I phoned Cherry Red and said, ‘Can we put it out on the él label?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, great.’ They were happy to have another Felt record.

The sound on Me And A Monkey is starting to move towards that of Denim, featuring chugging rhythms, analogue synthesisers and personal, direct lyrics looking back to a 70s childhood. These include the troubling ‘Budgie Jacket’ which seems to be about Lawrence as a child being sexually assaulted by an older man.

L: Yeah, it’s an odd thing that happened in the little village where I lived. It’s not a big deal; it never scarred me or anything. The gist of the song was about saying I used to look really good, like a little girl. And this guy mistook me; I think he thought I was a girl. And he took me to his house. But it wasn’t a big deal. It was nothing. We laughed about it afterwards, when I told my friends. Obviously it could’ve been something big, but it wasn’t. He was an old guy and he offered me some money, and I wanted it. And I think I wanted to say, these kinds of things can happen and they can be almost meaningless. It doesn’t always have to be a life-changing thing that scars you forever. And in 1989 when it came out it was kind of a controversial subject, and I always wanted to write controversial bits and pieces, so that somebody might go, ‘God, what about that?!’, and it’d be a talking point. And nobody ever mentioned it. Nobody ever said a word.

Denim – Back In Denim (album, 1992)

For the high-gloss glam-rock sound of Denim’s debut album, Lawrence recruited the original singer and drummer from the Glitter Band, Gerry Shephard and Pete Phipps.

L: I hated that bloody eighties that I’d been through because it hadn’t happened like I wanted it to. We weren’t famous; I hadn’t made any money; I wasn’t even a professional musician. I dreamed about being in the music business when I was a kid, and when I got into it, it was nothing like I expected. I was never in a limo, ever. There was no running to the back of the building to get in because everyone was outside and you couldn’t possibly go through the front entrance. We walked through every front entrance of every gig we ever did.

I didn’t know how to get that Glitter Band drum sound, so we used a sample on our demos. And then I was working in Bark Studio in Walthamstow and there used to be a pub on the corner, the Royal Standard, where they would have bands from the olden days playing. You’d get off the tube on Blackhorse Road and there’d be big posters on the front of the pub saying who’s playing that week. And when I went to the studio one day I went in and said god, guess who’s playing tonight? The Glitter Band are playing at the Standard! Let’s all go! So after we’d finished recording we went down there and they were playing in this dingy little pub, playing all of their hits. And I thought, ‘Oh my god; he’s the greatest drummer I’ve ever seen in my life!’ And the singer, Gerry, was still belting it out like they were at the London Palladium, even though there were only a few people in the audience. But it wasn’t until we got John Leckie involved a few months later that I said to him what I wanted to do, and he said, ‘I know that guy, because when I was working with XTC we used him as a session drummer, so I’ve got his number.’ We phoned him up and he was down within two days. And he was such a great character. He was a beautiful guy; lovely temperament. But we couldn’t afford to take it on the road, because he’d have to be paid a fortune. You couldn’t just offer him £50 or something. When we did the tour with Pulp it cost 22 grand, and that was just paying the band, the hotels, driving; it came to £22,000, for seven dates, so it wasn’t viable to put Denim on the road. It was too much money. That was the end of Denim, really, because we couldn’t play live. I was like if we play live it has to be with these session men, because they’re so good. And I was wrong. But I thought at the time it wouldn’t matter, because DJ culture had taken over so much and I thought live bands were dead. But actually the opposite happened and it was just the beginning of what we now know as indie.

I knew that house thing was exploding, and that culture, but I didn’t really like that and I couldn’t put myself in that situation. What I did wasn’t about dancing; it was about sitting in a living room with a hi-fi. That’s the thread that runs through it all: it’s about being on your own and listening to the music on your own, not being in a club sharing it. So I thought I’ve got to do something completely different to what’s going on at the moment, this Andy Weatherall DJ culture. So that’s when I came up with the whole Denim thing and placed it absolutely in London. I was living in New York and all I could think about was telephone boxes and taxis and all of these beautiful things in London. The railings that go up the street, you know; those glorious townhouses with the railings at the front, and all these great things. I was stuck in New York, thinking this is nowhere. This isn’t happening at all. I’m going to go back and do a London band.

The trouble was it took three years to make. I think if we’d got that album out in January 1991 it would’ve been different. But it was produced by John Leckie and then we had to scrap that and go right back to the beginning and start again with the tapes, because I didn’t like the mix. So it was a real struggle to get it finished. And by then it had cost a fortune, and lots of people didn’t get paid because London Records wouldn’t pay them. I was leaving bills left, right and centre and making enemies. It wasn’t good. But if it’d happened like I wanted it to I think it would’ve been different.

Denim- Novelty Rock (album, 1997)

After being dropped by London Denim signed to Chrysalis subsidiary Echo and released Denim On Ice in 1996, then were dropped again but picked up by EMI in 1997. Their only release on that label was the stop-gap album Novelty Rock. Partly a compilation of previously released B-sides alongside bizarre new tracks like ‘The New Potatoes’ and ‘Tampax Advert’, it’s actually Denim’s second-greatest collection. Much as Felt’s final album had anticipated the direction of Denim, the retro-modernist electro sounds and cartoon voices of Novelty Rock laid out the blueprint for Lawrence’s next band, Go-Kart Mozart.

L: I went from one label to another and I achieved the ambition that I had when I was starting the band in 1980, which was to be on EMI. And it was their hundredth anniversary, so every record that was made had this great ‘100 years of EMI’ stamp on it. And I believe we made the craziest album that EMI have ever released: Novelty Rock. Because it was on a sub-label, EMIDISC, we were allowed to do what we wanted. I was just making the songs crazier and crazier to get attention, and nobody was going you can’t do that. Nobody cared. I released one of the most bizarre records EMI has ever put out, ever.

Charlie Brooker recently chose ‘The New Potatoes’ from Novelty Rock on Desert Island Discs.

L: It’s amazing what can happen. You would never say that’s the song that’s going to get me a bit of attention. It was a song about potatoes that live in a field and end up being tinned and canned and going on a shelf and they quite like it. They like living in a tin. It’s a crazy song, but he liked it and he chose it as the one song he would take to a desert island with him.

It strikes a chord. I think a lot of us feel like we used to live in a field and now we live in a tin. We are the new potatoes.

L: That’s it, yeah! We are like potatoes.

Denim- Summer Smash (withdrawn single, 1997)

L: It was going to be a hit record. EMI said give us a hit record and we’ll sign you. So I did the demo of ‘Summer Smash’ and I took it in two weeks later, and the guy was sat there at his desk like they do on the telly when they show fictitious films about big A&R men, and he put it on and he said, ‘That’s a hit record.’ I said, ‘Well, you asked for one and I gave you one.’ And he went, ‘Right, you’ve got it. Who shall we get to produce it?’ And we got the guy who engineered all the Take That records. I couldn’t stand it, but I just thought I have to let them A&R me, and not stick my oar in. So it was going to be a hit. It was already trailed on Radio 1. It was single of the week on Mark and Lard’s show, which was dinnertime at that time, on daytime Radio 1, and it was going to be a hit record. And then on the Sunday, the day before it was going to be released, Diana died in a car crash. She died on the Sunday and they pulled it on the Monday. They talked about it during the week, destroyed all the records within the week and decided it’s gone, it’s not coming back, it’s finished. They destroyed it and dropped me. And I just couldn’t believe it, because we were literally on the verge of making it. We had an album. I had all the songs, and if that had been a hit they would’ve let me do an album on EMI and it just would’ve gone from there. So that was the end of that.

But it was life-changing, because I knew I’d actually made it to the top. That’s where I wanted to be. What do I do now? I don’t want to go back and try to get a deal with Virgin or somebody. I probably won’t get another major deal, and if I did it’s never going to be as good as EMI because EMI’s the top. So I thought I’ll just start my own label through Cherry Red. Because then I don’t have to ask anyone for any help, I don’t have to go begging at major’s doors. And it’ll look good, because I was on EMI and then I just did my own little label, and that was the whole Go-Kart thing.

Go-Kart Mozart- On The Hot Dog Streets (album, 2012)

Go-Kart Mozart’s third album is arguably their strongest, their funniest and their most troubling, as well as their best-produced. Musical and lyrically rooted in 70s and early 80s pop culture, it also draws on early noughties pop and UK garage as Lawrence vents his pain and confusion at the life he was then living. Alongside re-worked tracks originally intended for the unfinished fourth Denim LP and brilliant nonsense songs are dangerously ambiguous character pieces that, with hindsight, capture the dark currents in British life that would surface painfully in the lead-up and aftermath of the Brexit referendum.

L: I called Go-Kart Mozart a B-side band. It didn’t mean that they were inferior songs; it simply meant that you would take away the pressure of I’ve got to write a hit single, I’ve got to write an album that’s going to get in the top ten. It was that idea of, ‘Hey, listen to that mad song that’s on the B-side.’ But then in 1999, 2000, the bottom fell out of my life. I think I had a mini-breakdown to be honest. I’d worked so hard and my mind had been so focussed on trying to be famous for twenty years, I think I just collapsed, metaphorically, and I couldn’t function anymore. Even though I wanted to get on with the second Go-Kart record, I was trying to do it but I was doing it in a really haphazard way. That one took around four years to come out and then the next one took around seven. Real life caught up with me. Before that I wasn’t rich or anything, but I’d somehow managed to skate through it all and still been able to buy records and clothes or whatever. But I went from that to looking for money on the floor. On a Sunday I would go to a bench on the King’s Road, because rich people were there and they might give me a cigarette. I went from being okay to being absolutely penniless to being homeless. It was the craziest turnaround. And I went a bit mad. I definitely had a mental breakdown of some kind, and it was purely all to do with music, because I couldn’t do what I wanted to do.

Consequently, although I tried, I couldn’t get those albums finished. I wanted to do one in 99, one a year later and one maybe two years later; three albums within a three-year period. And that took until 2012, when Hot Dog Streets came out. My big regret at the moment is that I didn’t finish Go-Kart quickly, because the name doesn’t ring true anymore. It doesn’t sit right in these times. Go-Kart Mozart was purposely not a very good name because it had to be worse than Felt or Denim, because it had to be a B-side project. It wasn’t meant to turn into this huge bloody great long thing that’s gone on forever. I actually want to change it to Mozart Estate now, and that’s why I put Mozart Estate presents Go-Kart Mozart on the new album, because we’re getting ready to change the name. We’ve got a mini-album coming in September, and when that comes it’ll say on the back, this is the last Go-Kart Mozart record, we’re going away for an enforced holiday, when we come back we will then be known as Mozart Estate.

But time is running out. Mark Smith died last week. I can’t talk in terms of we’ll pick it up again in seven years, like I just said to you. Who knows what’s going to happen then? I might be too decrepit to even play live. So now I’ve got to think about time running out on top of everything else.

Go-Kart Mozart’s Mozart’s Mini Mart is out on Friday via Cherry Red. Felt’s A Decade In Music is out on the same day