The press has been awash with music plagiarism cases recently. From Ed Sheeran giving TLC’s ‘No Scrubs’ songwriters credit on ‘Shape Of You’ via the New Zealand National Party’s use of ‘Lose Yourself’ to the myriad claims around ‘Uptown Funk’, claims of musical borrowing have been rife.

Perhaps this is unsurprising. The music business is after all a business, and commercial issues often trump the cultural in this most volatile of industries. Add into the mix that all work is in some way derivative as it inevitably draws on what has gone before, taking and adapting, reshaping and repurposing, reacting and developing. To unpick all this is complicated.

Such a challenge surfaced recently with Lana Del Rey stating that she was subject to a plagiarism claim from the band Radiohead. The complexity in this case is compounded by a third party, in the shape of composers Albert Hammond and Mike Hazelwood. Radiohead’s composition ‘Creep’, Lana Del Ray’s ‘Get Free’ and Hammond & Hazelwoods’ ‘The Air That I Breathe’ share one musical element: an unusual chord progression rarely heard in pop music. They are also linked by a chain of infringement challenges, from The Hollies to Radiohead, and now from Radiohead to Lana Del Rey. The songs’ creations are decades apart – ‘The Air That I Breathe’ was written by Albert Hammond and Mike Hazelwood in 1972, and became a global hit for The Hollies in 1974. Radiohead wrote ‘Creep’ in the late 1980s and it was their first single release in 1992. ‘Get Free’ was the last track on Lana Del Rey’s 2017 album Lust For Life.

The musical similarities

Firstly, that chord progression; and it’s a beauty. In numerical terms it is referred to as I III IV iv. It has major chords of the first, third and fourth note of the scale, followed by a minor chord on the fourth note. In C major this gives chords of C, E, F and F minor. So although all three songs are recorded in different keys (The Hollies in C, Radiohead in G and Del Rey in B flat) they still sound similar because they follow the same chord progression.

A review of chord progressions from the website Hook Theory found that from 1,300 hit singles only one other song (Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’, from 1969) shared this structure. It’s the second chord that is striking. It moves from C to E major – a totally “unrelated" major chord, which creates surprise. From E it moves to the safer ground of F major (closely related to C), then to F minor, introducing a sense of melancholy, and back to C.

All three songs are slow (The Hollies 82 beats per minute, Radiohead 93 and Del Rey 103) which adds to the sense of similarity that the chord progression has already set up. The progression is repeated throughout the song ‘Creep’. It’s used only for the verse of ‘The Air That I Breathe’, and for the verse and pre-chorus of ‘Get Free’.

The Legal landscape

Chord progressions alone can’t assume copyright protection, but the melodies and lyrics that they underpin can. A song is actually a bundle of copyrights, with the lyrics attracting protection as a literary work and the music as a separate musical work under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The law forbids the copying of a whole or substantial part of a protected work, but unhelpfully does not define what is meant by substantiality. As we note on a blog on Lost in Music examining where the line in the sand might be drawn:

“Music is the product of an infinite number of different notes of different lengths, with chords underpinning the melody, framed within 24 possible keys, scored for countless instruments, set to an infinite number of possible words, conceived of limitless structures. Owing to music’s structure and its infinite creative possibilities, we can only strive to move closer to a definition of the point at which an infringement of copyright occurs."

So infringement is something of a grey area, and while there have been a number of legal cases that have examined the area there is no foolproof test that can be applied, but rather a set of guidelines, informed by expert evidence that can be applied. Sometimes the line is very finely drawn and both sides may find themselves stuck in the middle unable to come to a definitive answer.

The genealogy of the dispute

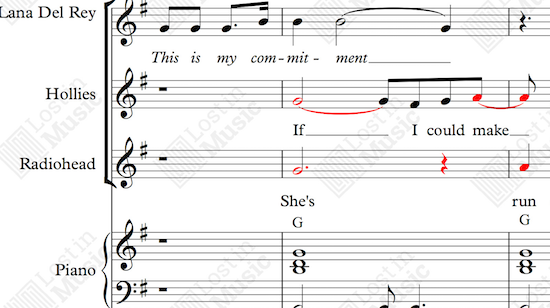

Most of the melody of ‘Creep’ doesn’t come anywhere near that of ‘The Air That I Breathe’ – its verse and chorus follow an independent course. But towards the end there is an improvised ‘break’ where Thom Yorke sings high falsetto to the words “she’s running out the door again", and here, for four bars, or ten seconds, the melody mirrors that of the verse of ‘The Air That I Breathe’. Possibly a nod of the head in tribute, possibly subconsciously, but it’s there. The illustration below shows in red the notes that are common to ‘Creep’ and ‘The Air That I Breathe’, adding Lana Del Rey’s melody to show that it is quite different.

The Air That I Breathe (Hammond/Hazlewood) Ⓒ Imagem Songs Limited.

Creep (Selway/Yorke/O’Brien/Greenwood/ Greenwood/Hammond/Hazlewood) Ⓒ Warner Chappell Music Ltd/Imagem Songs Limited.

Get Free (Nowels/Grant/Menzies) Ⓒ EMI Music Publishing Ltd/Cosmic Lime (ASCAP).

The original upshot was that in the early 1990s the writers of ‘The Air That I Breathe’ contacted Warner/Chappell, Radiohead’s publisher, claimed infringement, and a settlement was reached. The terms of the settlement are confidential but are likely to include cash to account for past royalties, an agreed share of future royalties from ‘Creep’, and probably no admission of liability from Radiohead.

Mathematically, the similarity in the two songs is in the melody (not the lyrics) of ten seconds of a four-minute song, or four bars of an 88-bar song. That works out at something like 2%. The essence of ‘Creep’ is not in this brief falsetto break, but in its haunting, genuinely “creepy" verse and its self-loathing, aggressive chorus.

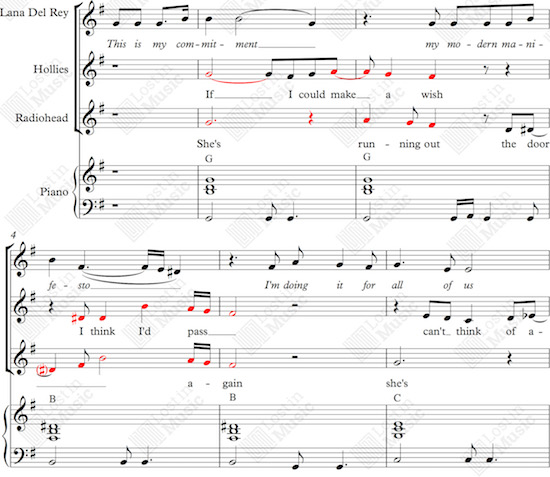

Lana Del Rey also shares melodic material with ‘Creep’, but with different parts of the song. In other words, Del Rey doesn’t copy ‘The Air That I Breathe’ at all. The 16-bar verse of ‘Get Free’ and ‘Creep’ share a lot of melodic material. Something like 24 of 44 notes are identical to both. Where the notes aren’t identical, the shape of the melody still is. It is fair to say that Del Rey’s verse is based on that of ‘Creep’. The first eight bars of both are shown superimposed below with identical notes in red:

The chorus of ‘Get Free’ shares similar melodic material for its first half only, or four bars of eight, as illustrated below:

Thus, we can do the same maths as for Creep and The Hollies, and calculate that, of the 52 bars of ‘Get Free’, 24 reference melodic material from ‘Creep’, 46% of the music, or 23% of the whole song, taking into account the wholly original lyrics in ‘Get Free’.

Whereas ‘Creep”s use of The Hollies’ melody can be claimed to be subconscious, or at most a conscious nod of appreciation for a single, short moment, the same can’t be said of Del Rey. Here there is a repeated and considerable appropriation of key melodic elements of verse and chorus of ‘Creep’.

Bearing this in mind, the likelihood is that a settlement will emerge, rather than litigation and a court ruling, although the public posturing and counter claims of both sides and apparent lack of clarity of the intentions of both sides may yet see this evolve into a dispute. Interestingly, any royalty share settlement with ‘Creep’ would presumably include (possibly erroneously) Albert Hammond and the estate of Mike Hazlewood, who are now counted as co-writers of ‘Creep’.

So where do we go from here? Actually there are still plenty of notes to go round. There aren’t so many chords, but the infinite possibilities of melody mean that it is always possible to be original. It is clear however that plagiarism in music is under the spotlight now more than ever. The key of course is balance and knowledge. As founders of the free open access music legal resource Lost in Music the authors must declare an interest here in the role of education, and the need for resources and mechanisms for composers and other interested parties to learn about the often complex machinations of the music industry. The aims must be to try and achieve some balance, with musicians being informed, cognisant and careful while at the same time rights holders not being too prescriptive -recognising that whilst yes music is a business, the creative and cultural should not be overlooked.

Guy Osborn, Professor of Law at the University of Westminster and Simon Anderson, musician, composer and music publisher are part of the founding team of Lost in Music, a free open access music law resource which analyses all key legal cases in music plagiarism.