It’s happened before, it’ll happen again, and it seems most noticeable with guys, the men too often privileged and centered in humanity’s roar. Loud guys – not always loud themselves in day to day conversation, but maybe known for big thoughts, sweeping gestures, a ‘presence’ – have a moment. Something happens that they can’t brush off or brings them up short, makes them wonder what to do with themselves, and then they do something a little out of character. Then they seem a little smaller, withdrawn, perhaps humbler, perhaps bitter, maybe both. You’ve known them, you’ve seen them, you could be them. Maybe you changed your life, maybe you remember it as something embarrassing you try to forget. Maybe your friends and family see something good in what you did. Maybe they think you’re not all that changed, that you had it all planned. Maybe nobody knows exactly what to think, even the person who had that moment happen to them. That, in large if not exact part, is the story of Gary Numan’s 1981 album Dance, now being reissued on Beggars Banquet in a double-vinyl edition with various B-sides and tracks from the era.

Often Dance, his fifth album in five years counting the Tubeway Army releases, makes me think of two later albums, made by musicians who have openly spoken of Numan as an inspiration – Kanye West’s 808s And Heartbreak and the Smashing Pumpkins’ Adore. Both West and the Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan had become massively famous after years of woodshedding and then a series of higher profile breakouts. But then both death – West’s mother after complications from surgery, touring Pumpkins member Jonathan Melvoin after an overdose – and drawn out romantic collapses (West’s engagement, Corgan’s marriage) shadowed their follow-up efforts, albums that seemed to go against all that they’d already achieved. It’s an exaggeration to say that but not entirely: West’s shift to singing with vocal treatments, a Roland TR-808 and a quieter approach and the Pumpkins’ shift to a more audibly spacious and electronic sound with less guitar shredding all around, neither were what had gotten them to where they were at before. That is definitely the story of Dance and Gary Numan.

There’s a key difference between those two later albums and artists, of course – whatever initial confusion resulted, 808s still turned into a solid commercial success, with massive hit singles and, over time, an absolutely clear impact on so much music, hip hop and beyond, in its wake, not to mention continuing fame for and high profile work from West, who will now be famous for being famous for decades to come. Adore in contrast was the clear turning point of the Pumpkins’ and Corgan’s fortunes, never again quite getting as big as they had before; the tours got a little smaller all around, and Corgan began his drift into the cult artist status he’s held since – high profile enough in turn, a known figure, a part of popular musical history, but the hits aren’t there any more, and new work gets endlessly compared to the past first and foremost. That too is the story of Dance and Gary Numan, in a different time and a different scale.

It’s worth remembering the exact context of where Numan was in his life and the role he held when Dance was released. Setting aside the question of personal upheaval for now – thankfully, unlike West and Corgan, no death was involved – Numan had, almost out of nowhere, singlehandedly hotwired a mass audience to consider an approach in pop music that embraced and interpreted 70s science fiction, glam’s lingering impact, punk’s brawl and, above all else, synths used not as excuses for neoclassical flourishes or for inspired funk workouts but, taking open cues from German pioneers like Kraftwerk, as chilled, blunt elements, simultaneously atmospheric and centrally melodic and, in Numan’s hands and combined with his amazing ear for the right rhythms and beats for his songs, totally anthemic and huge in sound and feel. At the start of 1979 he was 20 years old and utterly unknown beyond a small clutch of listeners, mostly in Greater London, thanks to Tubeway Army’s debut singles and album. By the release of Dance a little over two and a half years later he was 23, had toured the world, broken America with one big hit, topped the UK chart with two, not to mention having three chart-topping albums as well, and had played what he’d already termed his farewell shows with a three-night stand in London’s then-biggest indoor venue, the Wembley Arena. (And a further illustrative note of comparison if you’d like: the Smashing Pumpkins’ first album Gish came out when Corgan was 24, Kanye West’s first mixtape Get Well Soon… when he was 25.) Numan was fully appreciative of what had brought him that far so fast already, but he openly wanted to try something more.

It’s worth remembering that this all happened in a huge rush not merely to a very young man but, as he’s freely noted in later years, a very young man who wasn’t merely a loner growing up but also had and has Asperger’s. With a loving and supportive family all the while he wasn’t ever completely at sea but where human interaction exists on a slightly different level beyond the comfortable and familiar, things can be unsettling to say the least, the more so in a time and place when the two major outlets for any public announcements – the tabloids and the music press, especially wherever the one might bleed into the other – required that kind of interaction. Numan, freely and happily able to lose himself in the studio for as long as it took to get to grips with the initial rush of electronic possibilities, found himself less comfortable with the situations like he described later with his then-girlfriend Debbie Doran’s friendliness with characters in the London criminal underground. When after their breakup Doran approached the tabloids with her side of the story, it didn’t help his mood in the slightest.

Dance grew out of all of that and more – as any number of other musicians and DJs rapidly realised what further pop and dance possibilities Numan’s approach had opened the door to, following fall 1980 dates in the US for Telekon he laid low and created what in essence was his first real solo album. Even as past albums had had guests and experiments in arrangement, a core group had followed through in studio and live settings, and still would the following year at the Wembley shows, his only dates all that year. Dance is much more of a fluid affair, with regular standbys like bassist Paul Gardiner and drummers Cedric Sharpley and Jess Lidyard appearing here and there along with others, including, very notably, Queen’s Roger Taylor – laying down some of the few big brawling beats on songs like ‘Crash’ and ‘Moral’ – and two members of Japan: guitarist Rob Dean on ‘Boys Like Me’ and, even more crucially, bassist Mick Karn, whose immediately recognizable fretless work appears off and on throughout the album right from the start, as well as his saxophone playing.

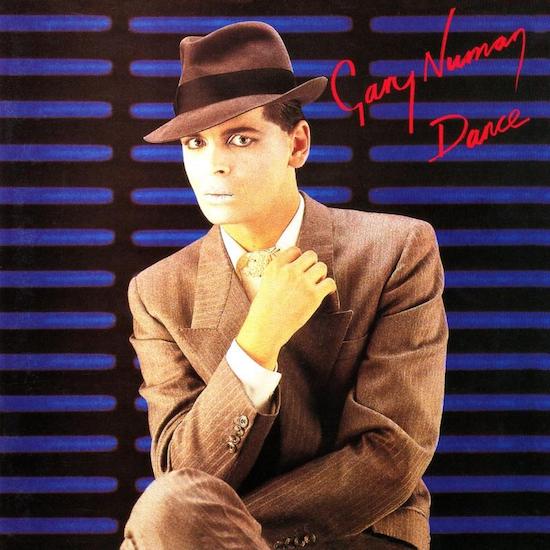

Dance isn’t a crypto-Japan album by any means, though David Sylvian himself was tentatively approached for the sessions as well, but Numan clearly appreciated how the act had similarly transformed themselves over time and brought even more individual touches to their work together. It was a recognition of others who were generally simpatico with Numan’s musical background as well, in the same way that Ultravox’s keyboardist Billy Currie had joined Numan for The Pleasure Principle sessions and tour, and how Numan openly acknowledged John Foxx’s impact on him in turn. Ultravox, Japan and Numan weren’t the only Bowie-and-Berlin (and Dusseldorf) obsessed acts in the country but they’d put themselves out there and everything was suddenly sparking, everyone levelling up and refocusing. Numan didn’t completely mothball an approach, but he fractured his own model dramatically, and did so via numerous changes at once: minimal electronic percussion reminiscent of Cluster and Brian Eno, two of the longest songs he’d ever done, a visual shift from vague futurism to fedoras and suits to go with even more makeup, and a general sense, one or two songs aside, that everything had gotten calmer, quieter, more introspective, but no less electronic or textured. It’s not a sound of exhaustion, but one gets the sense that, creatively, Numan wanted to at least take a deep breath and pause.

There were other changes as well. Perhaps aside from Tubeway Army’s debut, Numan had managed the pretty sharp trick of concept albums that weren’t labelled as such from Replicas through Telekon – the storylines could be there more vividly if you cared to focus, most notably on Replicas, but he’d spent even more effort at near-perfect sequencing and larger concepts instead. The albums all had a perfect flow to them, their respective visual designs marked each as different, and even something as simple as The Pleasure Principle‘s one-word-only songtitle restriction helped to create a sense of self-contained universes. Dance throws that overboard entirely, and the result is weirdly thrilling – it’s not simply a random collage, but it’s intentionally imbalanced (the two long songs both end up on the first side) and if there’s a storyline it’s unclear.

But there are stories. (And ‘Stories,’ per a song title: a near-winsome number about a long-separated mother and song meeting by chance in a restaurant setting with the suggestion of something out of a film, a scenario constantly retold.) To say Numan partially used the album to process his breakup from Doran puts it mildly – indeed, from the perspective of 2018, some sentiment feels especially curdled. ‘Slowcar to China,’ the opening number and one of the two near-ten minute numbers, is a beautiful and mysterious track musically, a statement of purpose for the album as a whole and utterly unlike anything he’d released up until that point. Though apparently the story of a prostitute, to some degree it feels like a vehicle for his collapsed romance, however unfairly, and lines include ‘She’ll pay the rent for the use of you tonight’ and ‘In love with this elegant bitch… and here am I just a shy young fool’ are especially vicious. Yet there’s also a suddenly affecting line like ‘We’ll sing without voice, without heart, and leave no address.’ If it’s indeed a young fool’s feelings, they can resonate just as strongly decades down.

Meantime, the barely restrained hints of homoeroticism that had permeated so much of his earlier work take a further turn here as well on any number of the songs – if admittedly a voyeuristic homoeroticism, Numan talking about it later as someone who had observed situations and been approached, and nearly always shot through with an air of seediness as a default. ‘Boys Like Me’, with a truly slippery and compellingly weird arrangement via Numan and Rob Dean, has pride of place thanks to the title, but ‘A Subway Called ‘You”, ‘You Are, You Are’ and ‘Night Talk’ among others contain further instances, the latter also addressing drug addiction with an air of anger and desperation. An even more striking combined lyric along those lines originally appeared as a guest appearance for a solo single by his regular bassist Gardiner, included here among the extra tracks. ‘Stormtrooper In Drag,’ released by Gardiner a couple of months before Dance and featuring both Numan and his brother John Webb, is a glistening monster of a song, sounding like something that should be on a playlist with, say, Laura Branigan’s version of ‘Self Control,’ an urban nighttime vibe that’s both threatening and compelling. Numan’s lyric is a compounding of both sexual suggestiveness – the title alone, but also lines like ‘obsessions with boys on the floor,’ ‘love cries like some boys cry,’ ‘I could call and make you crawl into bed’ – and drug horrors, itself likely pointed at the heroin-using Gardiner, who would die of an overdose three years later, and suggesting further undercurrents. ‘It’s so disgusting, I’m so tired of the rhythm/And needles in arms/And I don’t want your point of view’ sings Numan near the centre of the song, and the whole feels like a way for him to communicate what he couldn’t as openly or easily say to Gardiner otherwise – not necessarily love, but a companionship ultimately cut short.

Musically, throughout Numan seems to be not merely subverting expectations but finding ways to recontextualise his immediate musical past and look beyond it – most obviously on the concluding bleak rock crunch of ‘Moral,’ a murky as hell remake of ‘Metal’ from The Pleasure Principle that’s a sarcastic trashing of the New Romantics in his wake right from the start of the lyric. (An extended version of ‘Moral’ is the one wholly new track on this reissue – all other bonus cuts and contemporaneous B-sides appeared on the 1999 CD reissue of the album.) Yet it’s also heard in the way that the majestic keyboard swoops on ‘Are ‘Friends’ Electric’ are echoed in the distant and spectral shades on ‘Night Talk,’ or how the album’s one single, ‘She’s Got Claws,’ is as directly catchy as what had become notable hits before, but with Karn’s saxophones, calmer midsong breaks and a more overt suaveness all around – even while Numan’s lyric, as the title indicates, is a clearly pointed one aimed at Doran. Perhaps above all else it’s heard in the way that Numan’s obsessive love of strong rhythms plays out – the soft bursts and beats of electronic pulses, often touched with gentle echo, are nearly always played first and foremost in the mix, and he hangs the song’s hooks around them with the same catchiness as he had readily demonstrated over nearly everything he’d already released. It’s not art-rock, it’s art-pop, but transformed, extended.

Perhaps no song shows this best on Dance than the other lengthy one, ‘Cry The Clock Said’, capturing deep blue melancholia with precision and skill, a further processing of heartache. With its steady beats almost like a rhythmic patter of raindrops, a guest appearance by Canadian prog figure Nash The Slash on violin adding delicately mournful touches, keyboards softly sparkling then withdrawing, a lead melody played with calm deliberation, Numan’s clipped lyric delivered with a wounded yearn, it’s easily one of his most affecting numbers then and now. His spoken-word break can barely be heard, a self-rumination, and if the joke is to say that the robot is finally human, a better take is to say that there aren’t many songs like it anywhere that capture the shocked emptiness after a decisive break, like the heart steadily beats but there’s not much to warm it or comfort it.

When Numan played those Wembley Arena dates a few months before Dance came out, he and his band played ‘She’s Got Claws,’ but there’s also a shortened ‘Cry The Clock Said’ sonically arranged with the same understatement as the studio version, with Nash the Slash performing his violin part. You can hear that on the Living Ornaments ’81 album released years later, and quite literally it’s like nothing else during the entire show. The otherwise vocally charged up crowd is given to individual cheers here and there – you can definitely hear some ‘GARY!’ moments – but they’re more generally silent, probably somewhat unsure about what was on offer on the one hand, but perhaps just as easily entranced by its unfamiliarity on several levels. A slow, steady clapping along begins about halfway through that lasts for a bit, until a sudden burst of cheers heralds Numan’s short vocal turn towards the performance’s end. The loud-by-implication guy, the big-sounding band, the huge music, the experience they’re singing along with for nearly every other song (even the otherwise more familiar quiet ones – check the full throated roar on ‘Please Push No More,’ and that was an album cut) has effectively undercut expectations across the board and forced a different kind of response. If this, more than anything else, was the sign made visible that’s when things would forever change for Numan, then quite honestly, it couldn’t have been more beautifully done.

Gary Numan’s Dance is reissued by Beggars Arkive on 2xLP purple vinyl, Jan 19