In the six-and-a-bit years I’ve been writing these anniversary pieces, a working pattern has evolved that seems to provide a reliable framework. I spend the weeks leading up to the deadline listening frequently to the record I’m reappraising, reading through old magazine cuttings and books, maybe listening to old interview tapes where they exist, and generally re-immersing myself in the mood and mindset of the time it was made, plunging as deep as I’m able to get back into the music and its contexts. This is never usually a chore, as these are some of my favourite records of all time.

This time, though, that hasn’t been possible. tQ editor John Doran and I have tended to agree the schedule for these pieces early in January, and the publication timetable is dictated by the original release date of the album in question. So, since the beginning of 2017, I’ve known that my final piece for the year would be on this deliberately and irredeemably ugly record, its cover sitting in my mental to-do list like an ominous tombstone, sometimes hidden behind other work, often looming over it. As the dread day of the deadline approached, I found myself moving from an initial reluctance to listen to it, through a period of stubborn refusal, before bowing to the inevitable and finally playing the damn thing again at what was, if I wasn’t to incur John’s fearful wrath by delivering the piece late, the last possible moment. I managed it all the way through only once – a sliver of the level of attention I usually give to records I write about here. Whether that was sufficient is for others to judge: all I can say is, it’s as much as I could handle.

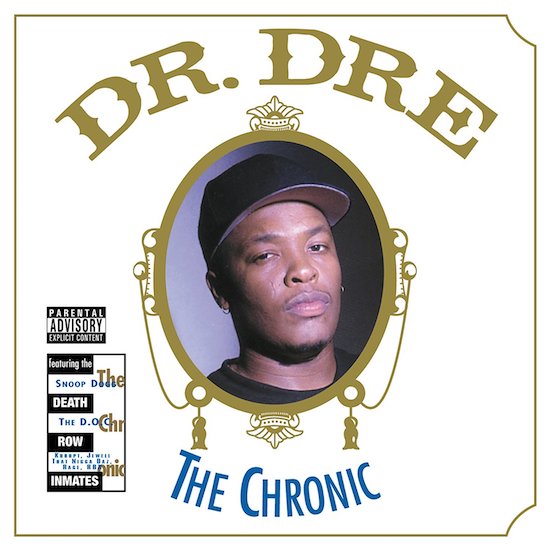

The Chronic is an important record, but it is repulsive and hate-filled: an hour of often superb, meticulous production laced with misogynistic and violently sociopathic lyrics, imbued with humour that would be given excessively undeserved praise if one were to label it as "puerile". It was a tough record to like at the time of its eventual, much-delayed release at the end of 1992, but today, in the age of Black Lives Matter and #metoo, and especially coming after the self-serving and blatant revisionism of the Straight Outta Compton film, it is pretty much impossible to listen to if you plan on keeping your breakfast down.

There are two – maybe two-and-a-half – tracks that rise above the sub-gutter level of the rest of the record. ‘Lil’ Ghetto Boy’ proved that Snoop Doggy Dogg, the accessory-to-murder suspect with the lazy flow, could write seriously and perceptively when the mood took him. ‘Let Me Ride’ re-worked a Parliament riff to provide Dre with a rare solo track on this supposed solo debut, and saw him turning the wearying, brutalising repetition of the n-word and the b-word into – all too briefly – unifying terms of apparent communality. And ‘Nothin’ But A "G" Thang’ remains a hip hop counterpoint to Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’, an anthem of alienation, a celebration of a bewildered generation’s half-enforced, half-chosen aimlessness, so deserves acknowledgement of the weight it attempted to carry. There are also some good lines from The Lady Of Rage, who clearly spent longer and worked harder on her verses than her male colleagues: she would pay the price for her insolence in showing up their slovenly, often incompetent displays by being shoved to the back of the post-Chronic release-date queue, only able to release her solo debut after all of the momentum she tried to build here had been lost.

But, that apart, the rest of this album is just rubbish. Read any of the commentary written about it in the years since, be it from journalists or fellow hip hop artists or even the sleeve note from QDIII that appears in the The Chronic: Re-Lit reissue, and you’ll find no shortage of people willing to queue up to pay homage to Dre’s prowess as a producer. Try, though, to find serious praise for any of the lyrics on this record, and you’ll find only rote testimonies to Snoop’s languidness, some discussion of the content of the numerous lyrical barbs aimed at Dre’s former NWA co-conspirators, and the occasional attempt to characterise the overarching hatefulness contained within the grooves as some sort of implicit social commentary – that these are dark rhymes for dark times committed to vinyl because their authors believed in furnishing their listeners with unadorned visions of bleak realities.

Perhaps it’s possible to see these splurges of verbal violence as automatic responses to a life of crack-fuelled gang violence, much in the same way that vomit and diarrhoea are symptoms of gastroenteritis. But the writers and performers here had a choice in how that response was framed. To excuse their decision to respond to hate and violence with more hate and violence is bad enough: to laud the products of that decision as great art is indefensible. More to the point, if they really were so committed to "keepin’ it real", where are the lines about throwing a female TV presenter down a flight of stairs after grabbing her by the hair and repeatedly smashing her head against the wall? Dre was always very selective in the "reality" he chose to portray. (On the other hand, why expect consistency from the author of an album titled after a strain of weed, with a sleeve that pastiched a rolling-paper packet, and which celebrated the drink-and-drugs lifestyle of the indolent gangbanger, who, a mere four years previously, had rapped: "I don’t smoke weed or sess, ‘cos it’s known to give a brother brain damage"? Perhaps a defender of this doggerel will argue that it’s our fault for expecting anything better.)

The notion that all concerned could have done something worthwhile is impossible to avoid, because ‘Lil’ Ghetto Boy’ proves they had it in them – even if it does so as much by its failures as its successes. It relies almost totally on ‘Little Ghetto Boy’, a track recorded twice in 1972 by Donny Hathaway, once on his storied Live album, but also in a studio version with strings that was included on the soundtrack LP to the film Come Back Charleston Blue. Fair’s fair – the precise formulation of the billowing clouds of violins Dre conjures here do not appear in either of Hathaway’s readings of the song, and they embellish the new track in a spectacular manner. But the opening, the main riff, and the hook are all copped directly from the late soul man. Snoop raises his game and writes with an air of reflection, though the overall intention of his two verses is to cement the notion of the steel-hearted product of the prison-industrial complex rather than to truly echo the social soul-searching of the original. Dre’s verse, though better than anything else he delivers on the record other than parts of ‘Let Me Ride’, is forgettable: he presents drama in place of emotion, using the format of a cautionary tale to deliver an ultimately empty, nihilist message.

The decision to stick with Hathaway’s hook would be less startling were the rest of The Chronic to exhibit any kind of insight or intelligence, or to suggest anyone involved was seriously interested in questioning themselves and their motivations: instead, including it numerous times here simply demands we listen to Hathaway’s question – "What you gonna do when you have to grow up, and have to face responsibility?" – and ask it of Dre. In 2015, after the Stalinist revisionism of the NWA biopic prompted women he’d beaten to speak out, he eventually released an "apology" – not directly to any of his victims, but to the New York Times, so its demonstrable purpose undercut any notion of sincerity. Even after all the years he could have spent on finding the right words, it was mealy-mouthed, imprecise and unconvincing. (It was accompanied by a statement from Apple, who had bought his Beats By Dr Dre brand the previous year for $3bn, saying they thought he was a "changed man". If anyone’s making a list of intriguing pop-culture "what if"s, perhaps they could add one about whether Apple would have been as forthcoming in their support of a man who admitted beating women – and then both lied and joked about it afterwards – had that storm broken in the post-Weinstein era.)

In an interview with Rolling Stone to promote the film, Dre claimed that, while some of the accusations were true, others weren’t – but didn’t say which ones, thereby inviting fans to distrust all those who had spoken of his violence towards them. That means the abuse those women received from Dre’s "fans" on social media afterwards is on him, too. When Surviving Compton, a TV movie telling the story from the perspective of Dre’s former wife Michel’le, was scheduled for US TV broadcast in 2016, he threatened legal action to prevent it from being shown unless scenes of him beating and shooting at her were removed, arguing that she had "never sought medical treatment or filed a police report", according to a story published by TMZ that cited the cease-and-desist letter as its source. Which of these very recent responses Apple would choose to cite as the actions of a "changed man" remains entirely unclear. Twenty-five years after his decision to have Hathaway ask that question, we’re still awaiting evidence that Dre even recognises his responsibilities: he certainly hasn’t done anything in public that suggests he has faced up to any of them.

If ‘Lil’ Ghetto Boy’ is the record’s one half-hearted tilt at doling out life lessons, ‘Let Me Ride’ is its celebratory anthem. It’s the LP’s one truly great moment, a distillation of the G-Funk sound Dre had here perfected with a lyric that helps explain the environment in which this music makes the most complete sense. The song posits Dre on a day-long drive through the Southland in his low-rider Chevy, giving and getting props from male and female admirers, uniting the denizens of gang-war-torn Compton around a vision of easy relaxation. The sound perfectly frames the lyric, precision-tooled samples of Parliament’s ‘Mothership Connection (Star Child)’ tweaked and reworked so the synth line pierces the song like shafts of evening LA sunlight beaming out from behind a distant cloud. Of course, its impact and innovation is limited somewhat by the concept being lifted wholesale from Ice Cube’s ‘It Was A Good Day’, and there have been plenty of folks over the years who’ve argued that Dre copped the entire G-Funk sound from his erstwhile labelmates Above The Law: but, credit where it’s due, he perfected the form, regardless of who invented it.

The one surprise on having to reacquaint oneself with the album after a lengthy break is to find that what rests in the memory as its dominant sonic motif – those sharp-edged, high-pitched synth lines – aren’t quite as ubiquitous as memory suggests. They’re used on just over half of the tracks, and sometimes – as on ‘Lyrical Gangbang’ – they’re a mere detail in a soundbed that hews closely to an east-coast hip hop template. ‘Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat’ is traditional sample-based boom and thwack. ‘Stranded On Death Row’ shows how little need Dre clearly felt to reinvent an approach minted four years previously by EPMD, using the same BT Express sample as the Long Islanders had excavated for ‘So Whatcha Sayin” as his new song’s reliable, proven foundation. There are significant chunks of this album that make you wonder whether there wasn’t maybe a bit of a lack of confidence in the new direction: as if Dre was hedging his bets by keeping in a bit of something more ordinary and less individual, just in case the smoothed-out style didn’t catch on.

In other places, what you remember as analogue synth is something else. In ‘Lil’ Ghetto Boy’ their place is taken by strings, and the fuller, more lush orchestration is what makes the track work. Elsewhere, the whine actively gets in the way of what might have been. Compare and contrast Dre’s use of Leon Haywood’s ‘I Want’a Do Something Freaky To You’ on ‘…"G" Thang’ with how Redman used the same source material a few months later on ‘Rockafella’, a post-G-Funk track that took note of what Dre had done but didn’t take the view that The Chronic‘s success was reason enough to abandon hip hop’s traditions entirely. The Chronic may well have upended conventional hip hop thinking sufficiently to see it routinely cited the end-point marker for the music’s Golden Age, but, as profound and as depressing an impact as its huge sales were to prove, not everyone chose to follow, mute and helpless, in its bombastic, ignorant, self-absorbed wake.

The rest of the record, though, does play out in the present pretty much how one remembers it – just with less and less reason, with every passing day, that anyone should consider it a worthwhile contribution to the totality of human creativity. The spoken-word opening to the execrable ‘Deeez Nuuutz’, in which Snoop calls an unnamed woman, charms her with his apparent tenderness, before provoking her to hang up in disgust at his unfunny smut, provides a concise encapsulation of the knuckleheaded crap found across the LP. The record’s predominant lyrical themes are as depressing as they are banal. These boil down to: Dre, Snoop and their chums are great, and people they don’t like – male or female – will be brutalised, dismissed, raped; women are wonderful things to have sex with but if they express any independence of thought, word or deed they deserve nothing but contempt; gang violence is bad, except when Dre, Snoop and their retinue are the ones performing it, when it is heroic.

Most peculiar of all is the fixation with homosexual rape as a means of threatening or actually dishing out punishment. You have to assume that the intention in the many passages of the LP where this takes place was either to be terrifying or to be "amusing", as well as to reinforce the idea that the record’s makers had spent time in prison, where such behaviour appears not to be considered "real" homosexuality by the kind of intellectual pygmies the record was apparently designed to appeal to. Problem is, this stuff is only about 1.4% as funny as a dick drawn on a toilet wall, and it’s so ridiculous it can’t be taken seriously. Plus, nobody involved seems to have realised that it loses whatever already minimal effect it might have the more often it is repeated.

In the second track – as the curiously prudish album cover renders it, ‘F— Wit’ Dre Day’ – the album’s obsession with this reaches an early conclusion. The dozen-plus references to anal or oral rape in the song range from the anatomically improbable ("gap teeth in your mouth so my dick’s got to fit") to the gymnastically impressive ("with my nuts on your tonsils/while you’re on stage rappin’ at your wack-ass concerts"). The objects of Dre and Snoop’s imagined sexual violence are Dre’s former bandmate Eazy-E, whom he believed had cheated him out of royalties; Ultramagnetic MCs associate Tim Dog, who had deliberately provoked most of NWA’s circle with the childish but effective ‘Fuck Compton’ single; and Luke from the 2 Live Crew, who looked at one of them in a funny way once, or something. Yet, as the song closes with Dre and Snoop burbling on about how each man can "eat a big fat dick", the way their vitriol is expressed raises more questions than it answers. One of those questions being: how come Dre never made a record containing similar threats against Suge Knight? Dre’s departure from Knight’s Death Row label came amid allegations of financial improprieties very similar to those he’d made against Eazy; perhaps he even believed he was cheated out of royalties for this very record. Yet it was the 5ft-and-change Eazy who got the rape-fantasy dis record from the serial woman-beater, not the imposing former linebacker with the carefully cultivated reputation for extreme physical violence.

If, for some unfathomable reason, you’re still thinking about getting hold of a copy of the album, the version to go for is the European vinyl release from 1993. For reasons never made entirely clear, it omits the revolting final track, ‘Bitches Ain’t Shit’, in which Dre takes yet more pot-shots at Eazy and former NWA manager Jerry Heller, and Snoop writes a verse in which a fantasy simulacrum of himself apparently murders a woman after coming home from prison to find her in bed with fellow Death Row rapper Daz. No matter how strongly flavoured the production had been, it couldn’t have covered up the foul taste left by the lyrics ("Bitches ain’t shit but hoes and tricks… Gets the fuck out after you’re done") – so maybe that’s why Dre evidently didn’t even try, turning in a desultory G-Funk-by-numbers dirge that stands out for its lack of merit even on this LP. It’s been argued that these cowards knew no better; they’d been brutalised by a rigged and racist system and were victims themselves, who were turning their understandable anger on the wrong targets. Yet a year earlier, Cypress Hill had managed to make an entire hardcore gangsta-rap classic album without disparaging women once (B-Real even sent up rap’s apparent obsession with misogyny in 1993 with the line: "Catch a ho, and another ho – merry Christmas"). The best that can be said about the song is that it provides a fitting end to an abysmal album – a record almost entirely devoid of redeeming features.