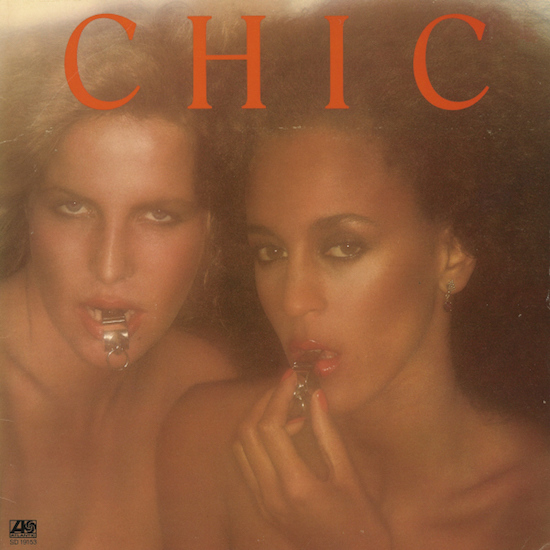

Whether anyone saw it that way in 1977, I can’t say. But to me, the cover of Chic’s first, self-titled LP has always looked as if it might just as easily belong on a Roxy Music album. Or rather, as if it were styled as a discofied version of a Roxy Music sleeve: two models (one French and white, it turns out, and one American and black, together blending into a kind of mocha satin – c’est Chic, right there), sleek, bare skinned, extravagantly coiffed and heavily made-up, whistles to their lips, ready to sound disco’s “beep! beep!” signature call.

I had thought of this as one of those bits of pop-culture serendipity, or at most atmospheric influence, that occur when there’s something in the air. It delighted me to learn Nile Rodgers was directly inspired by seeing Roxy Music when he came up with the concept for Chic. Chic were devised explicitly as “our black version of Roxy Music”. So I suppose I can say, after all, whether or not anyone saw the cover that way in 1977 – the man who created Chic did.

This matters in so many ways. It puts a spotlight on something that might otherwise have to be picked out of shadows. Chic, as with Roxy Music, were conceived in the pursuit of all-encompassing beauty. And just as Bryan Ferry’s background as the son of a farmhand who also tended pit ponies surely provided a powerful motivation for this pursuit, so too must Rodgers’ as the offspring of teenage New York smack addicts. In the hands of those condemned by birth to know much of the world’s ugliness, beauty becomes a political act. Which is not to say there was no beauty to be found in 1950s working-class Durham or in the druggie, beatnik Bronx of the 1960s. You’d have to ask the men in question about that. But probably not a great deal of the kind Roxy Music and Chic would come to epitomise; and certainly a great deal of the roughness against which they represent a reaction. It’s reasonable to think the 16-year-old Rodgers wasn’t spurred to join the Black Panthers by his life resembling a Manhattan society party, any more than the young Ferry’s did an Aquascutum photo shoot.

Yeah, but does everything have to be about politics? Not explicitly, no. But – a catch-22 – that question itself is politically loaded. To ask it, you will usually be either in a position not to worry about the politics involved, or so affected by it you don’t want to hear another thing about it. A great deal of life is about dealing with bullshit, and if you want a definition of privilege, then I can’t think of a better one than not having to deal with particularly insidious forms of bullshit that others cannot elude.

Still, can’t it just be about the music? Well, that’s the point. That’s what was so radical about Chic. The idea that in a world of insidious bullshit, something could just be about the music; moreover, about the whole experience of the music – the way it is, say, for people who go to the opera or the symphony, immaculately turned out, without having perpetually in the far recesses of their minds the niggling questions of whether they’ll make it back home, or if their possessions or their loved ones will still be there when they do.

That was what disco was: a music, a movement, a culture, originated by black people, gay people, Latino people, any-combination-thereof people, people who had more than their fair share of insidious bullshit to contend with. Disco stood outside that – and standing outside that was disco’s stand against it. It was, in the best sense of that tainted word, aspirational – it aspired to something finer. It aspired to a place where, at least for a little while, you didn’t have to think about that bullshit. Until you’ve had to think about it, on a daily basis, it’s hard to understand what a release that is. Richard Pryor once summed it up with typical lucidity, describing how being racially abused during an otherwise unremarkable confrontation, of the kind that might happen to anybody, takes it to a whole different level, one the abuser will never know: “Oh, great, now I gotta deal with this shit too.”

There can be few musical genres from the early 1960s onwards that include so little that is overtly political. Yet disco was deemed sufficiently menacing and subversive that it was subjected to a campaign to destroy it, the likes of which even hip hop and metal haven’t suffered. What was disco’s crime? On the face of it, the obvious one of being the wrong race, colour or sexuality. But if that was all there was to it, why have so many other genres and movements of which this might be said generated no reaction on that scale? Disco’s real crime was not knowing its place. Not knocking and holding its cap and saying please; nor being bolshie and militant and thus easily identifiable as a threat. Just walking into the room unbidden like it belonged there. And nobody walked that walk so serenely, with such poise, such nonchalance and such charm, as Chic. (It’s an ironic illustration of how quickly the music of the excluded becomes the preserve of the exclusive that their biggest hit, ‘Le Freak’, grew out of a chant of, “Aaah, fuck off!” – a sentiment aimed at the doorman of Studio 54, who barred them from entry.)

Chic is not a great album. It is a beautiful album, as befits its creators’ vision; but not, taken on its own, a great one. In the context of their own discography, it’s a set of scenic foothills before the alpine heights of C’est Chic (1978) and Risqué (1979).

What it is, however, is a blueprint for greatness. The DNA of every great thing that Chic would go on to do, under their own name or for others, is coded into it. The enveloping, pulsating warmth of ‘Lost In Music’; the blissed-out shimmer of ‘Spacer’; that extraordinary way they have of being simultaneously urgent and relaxed, of playing fast music that never feels frantic; that at times feels, in the most delicious way, loose and lazy, even though the band performing it is the tightest on the planet. It’s all on there.

It has two hits on it, one at the start of each LP side. Their very first release made the top ten, and it could hardly have set out their stall more plainly. ‘Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)’ is a fabulously made thing. Knowing the band’s catalogue, it feels a lot like what it is: a prototype. (Much of the album is brushed up from the demo tape that got the band signed, which tells you just how fully formed and perfectly honed a musical unit Chic were when they arrived.) It has all the essential elements that identify a Chic tune: drummer Tony Thompson’s metronomic yet fluid timekeeping; Bernard Edwards’s popping bass bubbling up and down through the percussion; Rodgers’ staccato funk riffs, simultaneously sharp as knives and smooth as butter, fluttering across the track with the precision of a robotically guided butterfly. “I didn’t even know what disco was,” the genre’s definitive drummer would later say, explaining that his bandmates turned to it faute de mieux because nobody would give a black rock group a hearing. Chic would expand on what they did. They would vary what they did. But they would never depart from what they did – and why would you, when you nailed it first time out, then kept on doing it better and better?

‘Dance’ was a song that was taking no chances. Chic wanted a disco hit and by God, they were going to make sure people knew it. The word “dance” is repeated over a hundred times; the remainder of the lyrics (in the honeyed, unfussy female-led vocals that would also characterise so much of their work) concern the dancing that has taken place, is taking place, or is going to take place. Between this and its comical “Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah” interpolation (the catchphrase of 1920s radio personality Ben Bernie, delivered in a mock black accent, and reclaimed by black Americans, in whose mouths it recalls a sardonic parody of “Yessir!”), the song has a whiff of the superior novelty number about it. It is absurd and magnificent and irresistible. It manages to contain everything that people who hate disco hate about disco; which is to say, it is brimming with a particularly exuberant expression of joy that joyless sods find particularly galling.

There is, however, nothing daft at all about their second hit, which is exquisite. ‘Everybody Dance’ is – obviously – identical in theme and purpose to its predecessor; it’s as if, having chosen the broad interpretation first time around, they then thought, “What if we go from the ridiculous to the sublime?” It is one of the most heavenly, light-footed tunes ever to grace a dancefloor, and anyone who is not, literally, moved by it should check either pulse or their soul. This was now the gold standard of disco, and while others would approach it, only Chic themselves would routinely attain it.

Between those two hits is the slight yet beguiling easy-listening Latin instrumental ‘São Paulo’, which glides by like the incidental music for a montage of jet-setting glamour, and the truly gorgeous confection that is ‘You Can Get By’. The most notable male vocalist on the first two Chic albums is Luther Vandross – who was, like most of the band, a seasoned session performer. His quicksilver tone runs through the backing vocals, sweetening and brightening all it touches. Yet the most notable male vocal is that of Bernard Edwards, whose lubricious, insinuating lead cloaks this sumptuous number in felt. The lyrics, unremarkable in their day, have not weathered the test of time so well: “You may not be pretty/ Oh but you can be, you know/ Take off those shabby clothes, girl/ And let your beauty show/ Make yourself a lovely woman /And get yourself a man/ Then you will be happy/ You can do it, yes you can.” Ah, but the sound of the thing. Your typical Barry White tune is positively ascetic by comparison. Edwards would never sing a major Chic hit, but his album vocal contributions are wonderful.

Of the remaining three tracks, ‘Falling In Love With You’ is an unmemorable smoocher, while the closing ‘Strike Up The Band’ is brisk, busy and brassy – and quite loveable, in a Muppet-ish sort of way. Much more intriguing is ‘Est-Ce Que C’est Chic’, which perhaps more than anything else on the album reflects the Roxy Music influence, not in sound but in spirit, combining exotica and heartache. Its chorus is in French, and Norma Jean Wright, native of Ohio, assumes a strange, breathy cod-European accent to perform its distinctly melancholy lyric. (Another thing Chic confined to their album tracks is any sense that life is not always an uproarious party.) Like many things on the album, it is wonderfully executed, but something of a curio – Chic on the brink of imago form, in musical terms entirely developed and utterly in command, yet still feeling their way conceptually towards the realisation of Rodgers’ ideal on the following two albums. In this, they are a mirror image of early Roxy, who were conceptually complete from the off, while giving the impression that musically they were (brilliantly, thrillingly) making it up as they went along.

Chic are, it should go without saying – but I’ll say it anyway, because you can’t stress these things enough – one of the greatest things ever to happen in or to popular music. It’s right that they should be emblematic of disco. Not just because they constitute its creative peak, but because from the very start they represented its unspoken social ambition – ambitious precisely because it was unspoken, because it based itself on the premise that you didn’t have to ask, and you didn’t have to tell; you just had to be. To walk in and take what’s yours with the same unselfconscious insouciance of those to whom everything is given. That ease, luxury and refinement, or at least your taste in these things, belonged to you as much as to them.

Man, did events prove that idea wrong.

Eight years ago, The Guardian published a (very good) piece in which Ben Myers asserted the Disco Sucks! Campaign of 1979 had, despite its initial success in crushing the genre and all it stood for, been a failure over time. “In an era when all music is just a click away,” he wrote, “when gay culture is embedded in the mainstream and America has a black president, it would be nice to think minds have expanded.” And in 2009, this was a perfectly reasonable thing to think and to write. In 2017, it is more liable to make one nostalgic for 2009 than for the age of disco itself.

Chic themselves, of whom only their original mastermind remains, have returned, and flourish as a touring act. Their catalogue, as artists, players and producers, is adored – as well it might be. But in America, the black, Latino and queer people – indeed, anyone other than white guys – who tried to walk in and take what’s theirs have been subjected to the most virulent backlash. Those who would have barred the door back then are once more in the ascendancy. The music remains glorious, the tacit message powerful; but the circumstances are grim. These aren’t the good times. Once more, music as joyous as Chic’s feels more an escape than a promise.