Over the past five years, artist, and musician Andi Magenheimer has lived and worked between London, Los Angeles and New York. This peripatetic lifestyle is reflected in the diversity of subjects she introduces into her paintings and drawings, and in her music, which she performs under the name ‘Dusty Miller’. Magenheimer’s spirited sense of humour and razor-sharp use of language are evident across art forms, whether in Self-Portrait as a Ham Sandwich (2017), or in the ‘sad cowboy’ songs she writes. Mindful of the conventions of painterly style and subject matter, she gleefully flouts aesthetic tropes and breathes new life into tired clichés. For her series of self-portrait collages, she posed in front of a mirror, hiding parts of her naked body behind matching paintings. More recent works toy with ideals of domesticity by depicting colourful and disordered interiors brimming with furniture, objects and bodies. Her solo exhibition at New York’s Gallery Sensei opens on 25 October, and her work can currently be seen in the exhibition Self-Indulgence at Hampden Gallery in Amherst, Massachusetts.

How do you get started on a painting, and what have you been working on recently?

Andi Magenheimer: I gather ideas every morning by looking at quite a wide range of news sources, from the BBC to Huffington Post to the New York Times or the Guardian. That informs my general cynicism! And then I have lots of coffee and I start combining ideas and trying to get, if not happy, then at least to be doing something until I can process it all.

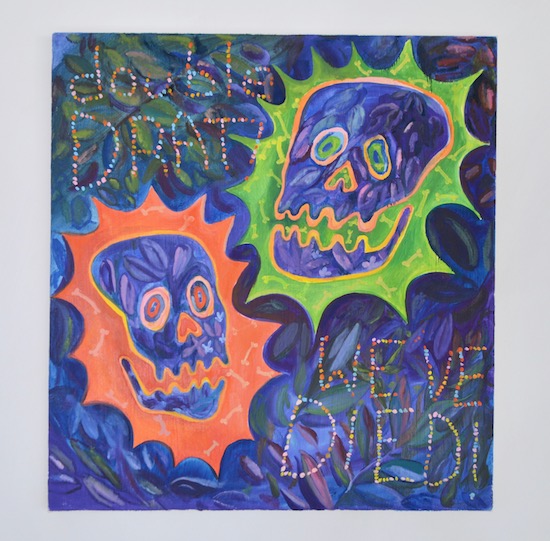

At the moment I am interested in skeletons, and I’m trying to push skeletons into being surprising and stupid and funny all at the same time. They are definitely overused as an art trope, not least with the memento mori device, but I think it is interesting to try to have the moment of death be a moment of surprise. People either take it too seriously or not seriously enough and there’s got to be a third way that involves jokes – for example, the animated skeletons in early cartoons.

I just finished a painting of a skeleton titled Forever Becky (‘My Name Is Not Becky’) (2017, which features the text ‘My name is not Becky’. This is a political painting in a sense. I was reading an article in The Root, a Black-oriented news website, which had listed all the different types of ‘Becky’. In the States a ‘Becky’ is a white woman who is not very helpful to the Black cause. The skeleton is in a defensive posture, with crossed arms. So there’s the question of what a ‘Becky’ is and whether, as a white woman, I am one too, but also the question of why a skeleton would be gendered or of a certain race.

There is a dark humour in your music as well.

AM: Yes, I play a lot of death songs. In all seriousness I think this began when a friend of mine’s brother was shot in Arizona, and at the same time I was going through a breakup, and a man was shot on my street in Los Angeles and my neighbour and I ran down to try to help. So death was everywhere, but it also seemed banal at the same time. It’s like the Talking Heads song ‘Heaven’, which goes ‘Heaven is a place where nothing happens’: death is in some ways the most boring thing that could happen to you.

I write sad cowboy songs too, and at the moment I’m working on recording new material with Ben Greenberg, a producer and music engineer in NY who also plays under the name Hubble.

Double Drat! We’ve Died! – Oil on canvas 71.12 cm x 66.04 cm

Your paintings have a wide range of references; with a treatment of colour that echoes modern masters like Raoul Dufy, compositions reminiscent of Picasso or Matisse, and punk sensibility that seems closer to some of the brasher artists of the 1980s, like Martin Kippenberger. Is this a conscious form of tribute?

AM: I am a thief and a scavenger! I have spent a lot of time drawing from nature and taking classes but the best way for me to learn is to question how other artists put things together on a canvas to make it look interesting. For example, I was looking at Cézanne for a long time and thinking about how he painted curved trees on the sides of the picture to create an arch effect on the rectangle of the canvas. It draws your eye in to the image with a glorious composition. I’ve tried to do something similar in my painting Bucket Mouth (my mom) (2017), where the hair on a floating face is coming in around the top of the image. The colour seems to slide around. There is actually an underlying structure to the image but the way the pigments are playing off each other on the surface seems so fluid.

I know that reading theory and literature is important for you. How do you work those kinds of ideas into your art?

AM: When I studied at the Royal College of Art, I was told to stop reading theory, which at first threw me for a loop but then I found it useful. There’s so much academicism running rampant in galleries, but I’m more interested in narrative, whether through song-writing or making pictures. I think it all comes out of a love for telling stories, which is innate in humans. I’m obsessed with Tolstoy, and I also love Fernando Pessoa. I got into his writing with The Book of Disquiet, but I think his idea of heteronyms, and being able to change who you are as a character and what style of work you can take on by changing your identity is really fascinating. So when Pessoa writes The Education of the Stoic as the Baron de Teive, he is able to be brutal with his thoughts, as an impotent, crippled, and incredibly rich character, who is turned down by a woman early on and then becomes a misogynist. It’s a gruelling look into a character created by Pessoa, who actually never left Lisbon. It shows that you can do so much with an eye for observation and your imagination.

Speaking of multiple personae, your work has gone through different phases in the past few years, from self-portraits to domestic scenes; what brings that about?

AM: Really big upheavals – like seeing someone die – can produce a change in style or technique or intention. Getting through things involves using whatever means necessary and that can mean starting from scratch with a new series, or going from painting with oil on linen to very scrappy drawings on newsprint or making a series of self-portraits as a sort of ‘fuck you’ to ex-boyfriends or to the idea that women are second-class citizens in a lot of places.

You’ve lived in three different cities over the past five years, and returned to each of them for shorter stays. How would you describe the main differences between London, LA, and NYC?

AM: I think that LA and New York are great for small music venues. London is really good for big art shows and galleries. For me, New York is the easiest to live in because it doesn’t take forever to cross town, you can find your people more easily, and it’s more compact. But that makes it more dirty and difficult in the winter. I think London is the most adult of the three cities.

What can visitors to your show at Gallery Sensei expect to see?

AM: There will be a group of bright beautiful oil paintings and related drawings. It’s my first solo show in a while, so I’m excited to be putting things together that haven’t been shown before. The show is on during Halloween so I’m also going to be showing some of my skeletons; happy-go-lucky surprised dead things.

Ellen Mara De Wachter is a writer based in London. Her book ‘Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration’ is published by Phaidon. Andi Magenheimer’s show Truck Full of Feelings: Paintings and Drawings by Andi Magenheimer, will be at Gallery Sensei, New York, from 25 October. Her work also features in Self-Indulgence: A Group Self-Portraiture Exhibition at Hampden Gallery, Amherst Mass. until 29 September