Tariq Goddard first shot to prominence with the superb Homage To A Firing Squad (2002), written when he was still in his mid-20s. Since then, he’s moved into the world of publishing but has also found time to write five further novels. Nature And Necessity, at just shy of 600 pages, is his best and most ambitious work to date.

The book’s title makes it sound like some unwritten Jane Austen work but that is doubtless deliberate, for in key respects, Nature And Necessity is anti-Austen – no coded formality or wry unspokenness or happy outcomes here. This is a novel whose guts sprawl across every page, its saga sprawling across more than three decades in the late 20th and early 21st century – though it has more in common with the maximal, realist novels of the 19th century. It’s about family life red in tooth and claw.

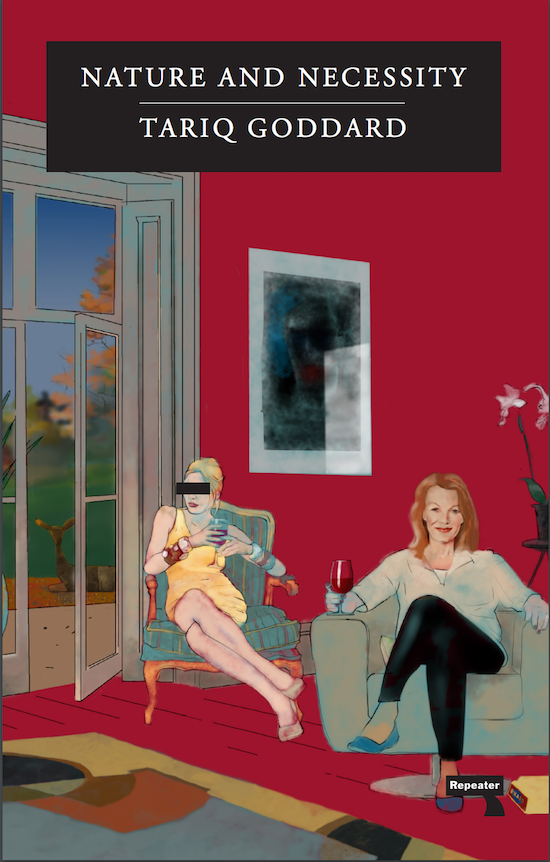

The charismatic monster, the Queen bee at the centre of Nature And Necessity’s hive of auto-destruction is Petula Montague. She lives in a grand property near to Leeds called The Heights, in a village called Mockery Gap, from which she presides judgmentally over locals and guests at her lavish dinners, on whom she depends to vent her contempt. She has had husbands but they have either retreated or been driven away; she lives off the wealth accrued by husband Noah, who apparently took a new life in the Philippines to be free of her. She has money, charm and privilege but ultimately does not know how to live, or to love for that matter. She has children, Jazzy, Evita and Regan but nurtures towards them competitive and undermining rather than motherly instincts, actively intervening to ruin their lives with tragic consequences. She is most attached to Regan, who she declares to be her “sister” but this is a relationship based on mutual fear and loathing as well as deep, fatally un-declared emotional dependency.

Petula is indifferent to sleep and hates silence or solitude, which brings with it the prospect of “being left on her own to meet herself”. She must busy herself with imposing on others, whether as social inferiors to be used as ersatz domestic help, or celebrities to be fawned over (including one to whom she exposes her children who turns out to be an abuser) in pursuit of a vague but intense ambition to ascend higher even than the Heights which blazes purely for its own sake. her life is ultimately a void filled by ingenious spite.

Awful as she is, Petula is strangely, hugely engaging (and would make for a magnificently meaty role for an actor in the vein of, say, Maggie Smith to play) is the fluency of her dialogue. Her every utterance is like a verbal battle tactic, an elaborately woven carapace, calculated to seduce, to wear down as well as speak elegant truths when it suits her. Of Regan’s father ands their broken relationship she says, “We simply became so much ourselves that we stopped being aware of each other except as characters bound up in our own fantasies.”

Only when she has her drink spiked at one of her lavish parties does her elaborate controlling mechanism break down (drink and drugs are often escaped to in Nature And Necessity, with generally disastrous consequences) but she emerges even from this calamitous episode enhanced, a 90s hostess/muse for the nouveau riche, international DJs and a Danish film director drawn in fascination to her dark allure. Yet she is still unable to live…

In the realist style, Goddard traces in detail the inner psychological unfurling of each of his characters, their secrets, their shames, their vulnerabilities and ignominious motivations. The phrase “be kind, because everyone is fighting a great battle” has been mis-ascribed to Plato. Each of the characters in Nature And Necessity is fighting such a battle, every day, every second, though there’s precious little kindness in this novel. Despite its occasional pop allusions (Pan’s People, 2000 AD, Southern Death Cult) this is not a satire of modern mores or celebrity culture. It runs deeper into the soil than that. In Larkin-esque terms, it is about the misery man (or woman) passes on to man, deepening like a coastal shelf. There’s a sense of an eternal struggle, a perpetual human failing as old as nature itself. It’s a misery, like a great Italian dish, to relish – this is a delicious read.

An Extract From Nature And Necessity

At last it had happened. The decision to kill Petula was one Regan and Jazzy came to on their own, without conference or the faintest notion that the other sibling was being edged towards the same desperate solution to what neither guessed was a shared problem. Nor did they hold the thought in its raw and reductive form, instead discovering, like a tadpole in a petridish, that it had been growing unwatched all along – Regan believing she loved her mother right up to the night she saw she hated her, and Jazzy long entertaining the notion that nothing would change until his mother passed, without recognising he willed that day on with all his heart, until it was forced from him. Theirs were separate journeys, taking very different routes, made at contrasting velocities, the slower reaching its

goal faster, and the quicker drawing the same conclusion later; speed for once being of no account in this race to a conclusion neither had forewarning of.

Like a voter who puts a cross beside the same colour at every election, Regan was too party-orientated to question the self-evident truth that her mother was wonderful, the pace at which she attacked life preventing her from focusing on the passenger left on the platform, in this case herself, mouthing back the opposite of what she thought was the truth. Jazzy, on the other hand, had less distance to travel, nursing so many conscious grievances against his mother that it was an effort for him to think of anything else, from the time he brushed his teeth, to passing out; the shock for him not that he hated Petula – he believed that all along – but that he loved her, and it was because he did that the only course left open was to stop her from hurting him any more. Their decisions, however, were identical in the relief they brought.

These decisions once accepted, neither brother nor sister had cause to consult the past again, question the righteousness of their motivation, or blame coincidence or bad luck for the parlous

desperation that drove them to leave the world they knew, and enter a secretive hell in which their most intimate imaginings and longings lay beyond the law. Both had heard it said often enough that if this or that had not happened, a certain conversation not overheard, the wrong bit of gossip not shared, the rain having fallen on that day rather than on this, then destiny would have happily resolved its tensions in a way compatible with everlasting satisfaction. This they no longer believed. The tale that life had fallen foul of malevolent chance, altogether too rosy and itself worthy of a Hardy novel, was pushed by their aunt Royce in an attempt to build bridges, without straying anywhere near

the sore core of their purulence, her optimistic characterisation of their dissatisfaction as accidental, too hopeful by far. Royce would have been better served consulting the Russian novelists

of the nineteenth century. Here she would have found a pushy and inexorable fatefulness, born of an eternally present horror, capable of being challenged at any time and therefore tragically

stoppable; had there actually been a possibility of the challenge succeeding and tragedy avoided. Regan and Jazzy lived through slights, slings, tedious lunches and spontaneous gatherings,

where all it should have taken was to ask Petula what the hell was she doing and could she please stop, to prevent the fall into criminality. Simple as this sounded, Jazzy and Regan had danced to variations of this tune for years, forever slipping up on the oily blatancy that underwrote their mother’s rule. All Petula had to do was simply deny that she knew what they were talking about and that there was any problem at all, only a mania the siblings had built up in their own minds, which is exactly how it would look to others once she had knocked their paranoiac querulousness into touch, and followed through with a speech that would shut them up for another two years. Regan and Jazzy would still be stuck with a version of themselves they despaired of, to be endured until its cause had gone, or, more likely, by their dying first (having never really lived), their mother scolding the undertaker for being late and reciting the funeral addresses over their coffins to a Cathedral packed full of her chums.

The step from conceding that only death, the black attendant, terrible and unconditional, would stop Petula from enjoying the last word, having exhausted the civilised problem-solving consensus, was a stroke from admitting that beneath this thought breathed another, with a crucial prefix: nature could not be expected to act on her own – if they were to enjoy the carefree mornings of a Petula-less future, it would need help. They would have, sooner or later, to pick up the slack reigns of their personal agency, otherwise Petula was going nowhere and nor, more as to the point, were they. Doing something in this context did not yet mean murder, and might even have entailed being able to persuade Petula to up sticks and leave the country, or convince her to simply leave them alone to live undistinguished existences away from her orbit and interference – these un-fatal remedies quietly

suppressing the one true solution over a decade of wishful prevarication and second thoughts, matricide still too preposterous for them to contemplate.