Some things are so big, you no longer see them. Some things, so pervasive you no longer notice them.

Who, for instance, are the most influential artists in popular music? Dylan, The Beatles, Bowie, The Velvet Underground, Patti Smith. They’re usually, and justly, near the top of any such list. But they shouldn’t be at the top. The question really being asked, and answered, is “Who are the artists you like who were most influential on other artists you like?”

The most influential artists of the last 40 years – and perhaps ever, depending on how one attempts to quantify it – are Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston. Nobody has had a greater impact on more music enjoyed by more people. Just not necessarily music you listen to. Not necessarily people you hang out with.

It was Brian Eno who made the now famous observation that the first Velvet Underground album sold only 30,000 copies in the five years after its release (mind you, plenty of bands today would consider that a major success, which is another matter), but everyone who bought it started a band. And, as Eno didn’t mention, a few of those bands flourished, but most sold even fewer. Jackson and Houston sold in the tens of millions; since then, people who sound like Jackson or Houston have cumulatively sold tens of millions more.

This doesn’t in itself make Jackson or Houston better than the Velvet Underground – whatever that might mean. Quantity is not quality. Might is not right. It’s simply how it happened.

Houston’s influence has diminished now. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the mode she established was standard for women pop stars – due not only to her huge commercial impact, but also to the influence of TV talent shows which gauged female acts in particular purely on technical terms: who was the most forceful; who had the greatest range, the most acrobatic melisma. As long as you could sing soul, you didn’t need to have it. This affected even the fresher and more imaginative Britney/Christina school; those girls required their chops to get ahead. Then along came Beyoncé, Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift, each with a different and novel way of being a superstar, and the spell was broken. Not that they can’t do all that stuff if they want to. But they don’t have to. For them, it isn’t the point.

Jackson’s influence on the men, conversely, is not just undimmed; it is – at least in the Anglophone world – definitive. If you are a male solo artist, and you sing and dance and entertain (on which counts Ed Sheeran scores one out of three), and you aim to be a major global pop star for any substantial duration, then you’re pretty much going to be Michael Jackson or die trying. Usher, Justin Timberlake, Bruno Mars, a host of other would-be’s and almost-are’s: it’s not just that they are indebted to him; they’re all but doing him. These are, to one degree or another, performers of considerable qualities who have made some very good music and staged excellent shows. But nobody in their field has as yet worked out how to do it significantly differently to the way M.J. did it.

Jackson’s single most influential work, obviously, is Thriller, his 1982 opus and the biggest-selling album of all time. I mean, how could it not be?

Except, a lot of the stuff that, whether by accident or design, still sounds like Michael Jackson – and whenever I make one of my occasional forays into the Top 40, I hear something that does; it’s not always by male artists, either – doesn’t sound that much like Thriller. It often sounds more like Bad.

Which in turn means that, 30 years later, Bad sounds weirdly current. Then again, it sounds weirdly everything, in that everything it does, it does weirdly. It’s a weird album.

Thriller sounds classic, because it is; classics are, by definition, timeless, even if they do recall a particular time. Bad does not sound timeless. It sounds exactly like 1987, and it is a curious turn of events that in the succeeding three decades, we have never ceased to hear things that sound like Bad. If that stopped happening tomorrow, Bad would suddenly sound very dated indeed. Which would not make it a bad record. Despite all the guffaws and banalities that greeted its title at the time, it is anything but bad. It is, as I mentioned, weird, and it is so absurdly variable as to be capricious, but when it’s good, it is blinding. Those post-Jacko stars I mentioned above? It’s not just that they couldn’t exist without Jackson. They couldn’t exist without ‘Smooth Criminal’ alone.

Thriller exudes the kind of ease you hear on an unimpeachably great record where everything has come together just as well as it could. Even if that wasn’t the story in the studio, even if that’s not how the people who made it feel about it – even if they were miserable making it – you can tell when the music itself has been struck by lightning. It took a lot of people to make Thriller, and every last one of them aced it. The sound may be on the synthetic side – that’s just how it sounds, as did so many records at the time, many of them all the better for it – but the feel of it is natural. It feels as if that’s the way it had to go.

Bad, by contrast, could hardly have felt less natural, in that sense. Or so it seemed then; Jackson’s subsequent, stilted work shows that it could have. But where Thriller had flowed, strutted, swayed, glided and moonwalked, Bad stuttered, shuddered, jolted and jerked. Nothing on it seemed quite human – least of all Jackson himself, whose vocal manner seemed to reflect his changing appearance, becoming hacked, shaped and re-coloured into a series of cartoonish symbols, signals, tics and gestures. Again, this is not an inherently bad thing. Weird as hell, but not necessarily bad. In retrospect, it is clearly the first step – indeed, several steps – towards Jackson’s work assuming the suffocating, joyless character it would later exhibit on such tracks as ‘Scream’: frantic, plastic, mechanical, shrink-wrapped. (The shiny, claustrophobic, space-capsule video for that song could not have been more apt.) That music is fascinating in its own right, and not a little unnerving. But Jackson wasn’t there yet. Bad is certainly airless, though. No wonder he gasps all the way through it as if desperate for oxygen. It is, in every sense, compressed, its sounds for the most part dry and taut. There’s no pliancy in the upbeat numbers – not an inch of give, not an ounce of fat, no soft surfaces, and only the faintest intimations of warmth. Even the smoochy numbers are curiously brittle: ‘Liberian Girl’, whose timid efforts at quasi-African fluidity are scattered and squashed beneath the crashing percussion; ‘I Just Can’t Stop Loving You’, which with kinder treatment might easily have been one of those sweet ballads Jackson turned out so ably in his teens, and to which may be accorded the backhanded compliment that it is the least fraught thing on the album, in part thanks to the calming vocal contribution of Siedah Garrett, she of that delicious Dennis Edwards collaboration, ‘Don’t Look Any Further’.

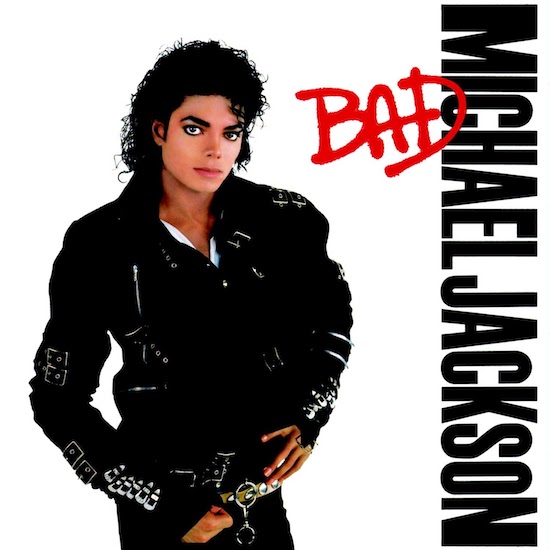

Because, make no mistake, this is one fraught record. In its sound, in its themes, in its overriding atmosphere. It is laden with grievance, with jittery defiance, with anxiety, with unconvincing braggadocio. That it was much more Jackson’s own record than its predecessor is clear from the credits. He was sole writer on all but two of its 11 songs (he had written four of Thriller’s nine). He took an album co-production credit alongside Quincy Jones. Yet if this was a liberation, it doesn’t feel like it. It feels like an artist straining at the leash, beating his fists upon his own limitations when all others have been removed. What motivated him? Did he feel the need to rival Prince’s prodigious abilities as an auteur? (Prince had been billed as a prospective duettist, likewise Whitney Houston; neither collaboration took place.) Were defiance and anxiety what he wanted to express now he had the chance, or was Bad itself the source of them? Here was a man, famous from the age of 11, whose strange and difficult life had made him the world’s greatest pop star, projecting himself on the cover as the street tough he unmistakably was not and could not be, a leather-encased hombre proclaiming on the opening title track just how dangerous he was.

Perhaps it was all theatre. For as long as we’ve had pop stars, they’ve played versions of themselves, or other people entirely. Acting a part comes with the territory. Plainly, Jackson was doing a bit; the question is, was he just doing a bit, assuming a new persona as part of the game, or was he signalling his own longing to be that way? With its stings and its drama, ‘Bad’ has a curious West Side Story-revisited quality. Its lyrics are far more abstruse than a simple throw-down, to the point of being nearly incomprehensible. Yet it’s difficult to shake the sense that this is who Jackson genuinely wanted to be. That like so many victims of bullying he yearned to transform himself into a hard nut, equipped with powers not just to resist but to humiliate his persecutors. And ‘Bad’ is an amazing song. Had it not been made by the recent creator of pop’s biggest ever album – had a hitherto unknown act recorded it – it might have been greeted as a remarkable experiment in catchy, neurotic avant-garde electro-funk.

The same is true for much of the album; if it seems an obvious pop record, in the narrower generic sense of the term, that’s because it was made by a person who was the world’s most obvious pop star. But for the most part, it doesn’t take the easy road. True, some things fit a template: ‘Just Good Friends’ and ‘Another Part Of Me’, closing the first side of the vinyl release and opening the second, are the very definition of filler, Prince/Jam & Lewis-derived products of their moment. Others are – again – more weird than anything else. ‘Speed Demon’ could be the soundtrack to a 1980s video game, and the notion of Jackson as an outlaw road racer is at once bizarre, hilarious and oddly poignant; Jackson has become what millions of others fantasise they might be, yet he implies again and again that his own fantasies are very different, and no more attainable for him than megastardom is for the rest of us. ‘The Man In the Mirror’ is a thoroughly dislikeable song; even though Jackson didn’t write it, it is the harbinger of the self-basting, sermonising style that would reach its apotheosis in ‘Earth Song’, occasioning Jarvis Cocker’s splendid spontaneous response at the 1996 Brits. But it wasn’t an obvious song. The obvious thing would have been to make it into a pious, saccharine ballad. Doing it as a thumping chunk of Formica gospel was . . . well, again, it was kind of weird.

Nine – nine! – of Bad’s tracks would be released as singles. At least five of them, including the title track, are bona-fide jaw-dropping belters. ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’ has the structure of a standard old-school rock & roll tune, but Jackson turns it into a swaggering, clattering, modern R&B showpiece, in which he gets to play the smitten, streetwise lothario he could never and would never be in person. ‘Dirty Diana’ returns to one of Jackson’s favourite themes – bad women who are out to do bad things to him. (In fairness, this is hardly a motif peculiar to Jackson, or even to pop music, although pop music has tended to specialise in it.) It rocks in that contained, uptight way chart rock had about it at that moment, but still, it rocks. It stings. Mind you, for Jackson to complain about anybody else’s sexual mores took some brass balls. As for ‘Smooth Criminal’, it was, remains, always will be, a dazzling, gobsmacking, electrifying tune. It is pure, breathless action, in every way: a movie scene magically transfigured into fierce, razor-edged, bastard-tight disco-funk.

When you consider that Bad starts off with the one-two punch of ‘Bad’ and ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’, and ends with the troika of ‘Dirty Diana’, ‘Smooth Criminal’ and ‘Leave Me Alone’, that is half of a ridiculously great album right there. That much of the other half is merely ridiculous is a pity. But ridiculous, in turn, beats bland every time, and aside from that dip right in the middle, Bad is never that. Jackson could hardly have made Bad less like Thriller. That’s just a turn of phrase. Obviously, he could have. He could have made an album of Andean nose flute music, or whatever. But he could hardly have made an album that was evidently the Big New Release by Michael Jackson, Megastar that felt more different to Thriller. It was a bold thing to do. And – as I keep repeating, but it bears repeating – it was a weird album to make. But then Jackson was, notoriously, a weird individual – and, it transpired, a monstrous one. It’s notable that he hasn’t been un-personed the way the still living Gary Glitter has. You might say he was too big to fail; I think it’s more that people love his music too much to relinquish it, so they just blot that side of things out. I do, so I do.

I remember seeing ‘Leave Me Alone’ on Top Of The Pops and staring at the screen open-mouthed in astonishment at the brilliance of its slamming, furious appropriation and retooling of Beatlesque harmony, instrumentation and (in the video) imagery. (It only now occurs to me, after all this time, to wonder if this might have been a coded memo to Paul McCartney to stop asking Jackson to raise the royalty rate on the Northern Songs catalogue Jackson had acquired after taking McCartney’s advice to buy publishing rights; just as McCartney’s ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ surely addresses Allen Klein.)

‘Leave Me Alone’ being the final track means Bad is a record that opens with the message “Fuck you!” and closes with the message “Fuck off!” Thus book-ended, it has, to date, sold 35 million copies. Maybe Michael Jackson was a pretty bad dude after all.