Photo: Wikipedia commons

Even in the strange world of the Japanese underground, there’s never been anybody quite like Keiji Haino. Improviser, noisemaker, guitarist, jazz man, poet, vocalist – he’s none of them and all of them all at once.

Keiji Haino’s main conceit seems to be that blackness, nothingness, and eternity are the common denominators in the universe – and thus they should be celebrated. So for over five decades he’s been doing just that, tearing the universe a new one with epic noise guitar rituals, pounding drum skins until they open up the fabric of space-time, and screaming so damn hard the cosmic din of the void gets temporarily disabled. Since emerging from the primordial ooze of Japan’s now mythical post-sixties underground, he’s steadily become an unlikely international icon of sorts – a noted noise music pioneer, a keystone in the bridge between free jazz and noise rock, and a champion of performance over craft.

So he’s not the kind of person you’d expect to see hanging around in, say, Selfridges for example – right? Well at the behest of designer Yang Li, Keiji Haino along with KK Null, JK Flesh, and Ramleh, are going to be not just visiting Selfridges but playing a series of concerts there this September. It’s odd and it’s dissonant and it’s unexpected – but so’s pretty much everything to do with Keiji Haino. It’s with that most unexpected end point in mind that we usher you through some of the key points in the dark, strange world of Keiji Haino.

From Jim Morrison to Albert Ayler

If we look back through the mists of time, we can see that Keiji Haino was a fresh-faced young theatre kid from just outside Tokyo who, believe it or not, had his key musical epiphany when he heard The Doors. Presumably it then only took a few art school listening parties to swap worshipping Jim Morrison’s theatrical performance for Albert Ayler’s freeform blast. Either way, Haino’s youthful musical epiphany somehow led to the ultra-harsh mutilated free jazz trio Lost Aaraaff.

The concept of the outfit was initially pretty simple. Take a piano-drums-sax trio and replace the sax with Keiji Haino’s wordless voice, but then inevitably guitar entered the fray, and the hum of feedback and his spontaneous poetry eradicated many of the semblances of jazz making Lost Aaraaff something closer to what we would now think of as a noise group. Touring Japan throughout the early 70s, they played many festivals, including Nihon Genyasai in 1971 protesting the construction of Narita airport (today the country’s second busiest), sharing stages with the likes of the Flower Travellin’ Band and Les Rallizes Dénudés, plus Japanese free improv pioneers like saxophonist Kaoru Abe and guitarist Masayuki Takayanagi, all of whom made a big impression on Haino it’s safe to say. Lost Aaraaff’s a fittingly raw beginning for Haino, but the sharpness of the sounds would later give way to the softer blackness of reverb and squalls over squeaks. Despite years of playing shows, outside of a handful of near-impossible-to-find compilation appearances, this self-titled CD released in 1991 (but recorded in 1970 when Haino would have been a mere 18 years old) represents Lost Aaraff’s entire recorded output.

Watashi Dake?

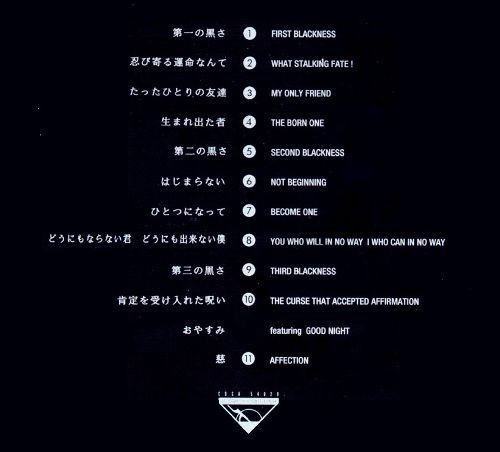

Watashi Dake? [Only Me?] was Haino’s first solo release, issued as an LP in 1981, re-released on CD in 1993, and recently re-re-released on LP. It certainly serves as a milestone moment, and Haino’s first cohesive full-length solo statement. The eleven tracks are uncharacteristically short for him in hindsight, but contain cemented versions of Haino’s most often utilised sonic tropes. Opener ‘My Refuge’ is an a cappella scream performance constantly threatening to pop a poor speaker in the studio as feedback skirts the room, ‘Rise From The Dead’ cycles a lumbering dissonant guitar figure while gently Haino mumbles, and ‘I Can’t Do It Properly’ backs up tortured singing with a blast of shuddering Merzbowian guitar noise. Pretty much every one of these sounds and ideas would get later expanded to epic album length outings all their own, but Watashi Dake? remains the breeziest and most succinct outing in Haino’s discography – and the essential gateway drug for new listeners.

Fushitsusha

Haino’s most enduring project, Fushitsusha actually formed back in 1978, essentially taking those bleak and noisy ideas and creating something vaguely resembling rock band shaped around them. The name, which roughly translates to ‘man without qualities’, continues to this day, but over the years Fushitsusha has referred to several different lineups. Back in the early days a synth player was involved, while other notable lineups have included Haino himself playing drums rather than guitar in a duo with a bassist. For the most part though, it’s the ultimate wig out group, digging into mind-melting, long form jams of epic guitar squall, rumbling bass and anti-rhythmic drums, and of course, some Japanese screams.

There’s a whole decade in the wilderness for this project about which we know next to nothing – the only document between 1978 and 1989 is a single archival release of rehearsal tapes. Come 1989 though, and a colossus of a masterpiece was released on Tokyo’s PSF label. Alternately known as Live 1 and 1st, or most commonly by its catalogue number PSF 3/4, it’s a double album of live recordings presumably made circa 1989, featuring two different lineups. The music’s some of the most accessible and musically direct Haino ever made, even harbouring some bouncy blues grooves. Opener ‘That’ even has a goddamn harmonica on it for fuck’s sake. Besides the bluesy grooves, there’s a lot of downbeat, gentle balladeering. Haino’s guitar leads also fiddle atonally around alien scales, but there’s not much in the way of the gut-punching energy and illogical rhythms that define all of Fushitsusha’s output thereafter.

Only ‘It Became, It Is, It Is Not’ seems to hint at the non-sequiturs and odd rhythmic patterns that came next. Epic closing track ‘Koko’ (‘Here’) is possibly Haino’s most often played piece of music, and by far his most beautiful. An six minute opening of angered riffing gives way to a sparse jazz chords ballad, crescendoing into a noisy lullaby that breaks your heart every damn time. The most satisfying and beautiful moment in his discography, PSF 3/4 is easily the album that’s won Haino the most followers.

Meeting John Zorn

When John Zorn’s grindcore project Painkiller recorded a live album in Tokyo in 1991, Haino jumped on stage for five spontaneous tracks, adding guitar and vocals to a glorious industrial mess. Unlike the rest of the live concert – snappy grindcore explosions for the most part – the Haino tracks on Rituals are longer freakouts, nudging the ten minute mark in one case. Zorn’s sax and Haino’s voice spar over the top of Mick Harris (of Napalm Death) and Bill Laswell’s rhythm section, opening the group up to directions that would veer the trio into dub and spacier territory in later outings minus Haino. The relationship forged with Zorn would also lead to trips to New York and countless collaborations with American musicians, as well as the release of several Haino-associated records on Zorn’s Tzadik label (including the brilliant Tenshi No Gijinka). Those Tzadik records still remain perhaps his most widely available pre-millennial releases of Haino’s, and Zorn’s approval undoubtedly went a long way to making Haino better known outside of Japan.

Endless Waltz

Endless Waltz by late director Koji Wakamatsu is already a strange enough film in its own right, but Haino’s brief appearance is especially unforgettable. Endless Waltz is a telling of the life story of Kaoru Abe, a Japanese saxophonist who pioneered a freer playing in the country and performed harsh solo sax shows that no doubt had a direct impact on Haino. Abe himself died of a drug overdose in 1979 at the age of 29, so is portrayed by Kou Machida in the film – but Haino portrays himself. In his scene Haino describes Abe’s erratic behaviour as an improviser (something which filtered over into Abe’s non-musical life of drugs and booze), saying "it wasn’t an issue when he was playing solo, but when we would play together he would piss us off." We’re treated to some footage of Haino and Machida blowing the socks off a jazzy crowd, and even a small snippet of a peak era Fushitsusha performance. Haino has always eschewed booze and drugs since Lost Aaraaff, stating that, "What I am doing is the real stimulant", but one imagines seeing the likes of Kaoru Abe and the many other Japanese jazz musicians die prematurely also had some effect on his attitude.

The Tokuma Years

For a brief period in the late-1990s, Keiji Haino was releasing albums via a short-lived imprint for major Japanese publisher Tokuma Shoten (they own Studio Ghibli amongst many other things). The results produced four of his most staggering albums, which include a collaboration with British free improv legend Derek Bailey (Drawing Close, Attuning – The Respective Signs Of Order And Chaos), a stripped back set of solo songs called Keeping On Breathing, plus his first outing with the hurdy gurdy, Even Now, Still I Think. The latter signalled the start of a new chapter in Haino’s solo performances, soon experimenting with percussion, loops, and synthetic drones. He deployed the instrument as the deepest of possible drone instruments, scraping his way through a slow moving hour of deep listening, eventually backing himself up with some tortured choir boy moans. In later years his instrumental arsenal outside of guitar and voice has included flute, cymbals, digital theremins, rudra veena, and more.

The Tokuma period also birthed short-lived trio project, Aihiyo. Mostly far quieter than your average Haino band, Aihiyo covered fifties and sixties pop tunes by both Western and Eastern artists, putting aside cosmic concerns to show off his romantic side (or his fun side even) for once. The trio covered The Ronettes and The Rolling Stones, alongside several Japanese artists of the era probably less familiar to Western ears. A personal favourite of mine is this version of The Zombies’ classic ‘I Love You’, released in 1998.

Painted black

If you’re going to explore the blackness of the universe, you’d better wear the right digs – and Haino seems to have decided this means black clothes, long black hair, black shoes, and black sunglasses whatever the weather. While Haino’s certainly donned the look longer than any other artist going, it’s been a staple of the Japanese underground for decades. As Julian Cope documents in his Japrocksampler, late-60s psychedelic group Jacks – more specifically lead singer Yoshio Hayakawa – seems to have pioneered the eternal Ray Ban and longhair look – check out the cover of their 1968 classic Vacant World. Similarly, Haino’s evil twin Takashi Mizutani who reclusively led legendary outfit Les Rallizes DéNudés, spent several decades sunglassed and clad in black from head to toe.

Recent years have seen Haino’s hair include tasteful strands of white and grey, and the 65 year old also often walks with a cool-as-shit black cane. Beside being some damn graceful ageing, Haino is truly living his art with these choices. He put it aptly himself in the title of a 1997 minimal drone outing: ‘So, Black Is Myself’.

Untranslatability

Saying I Love You, I Continue To Curse Myself, The Book Of "Eternity Set Aflame", Shall I Download A Blackhole And Offer It To You – Haino’s album titles and lyrics always take on their own strangely elliptical and philosophically coded form of poetry. Far from being a mistranslation of some histrionic dark gibberish, it’s another vital side of the man’s art. The words and titles themselves (in both English and Japanese iterations) are often spaced strangely in liner notes, split into rhythmic lines like a haiku that’s had too much to drink. Content wise, they offer the clearest insight into the man’s worldview for non-Japanese speakers. The recent remaster of Watashi Dake? included new English translations of the lyrics too – let’s have a look at what Haino-san is saying indecipherably on anguish ridden creaky closing track, ‘I Want To Return’:

I want to return to that place from whence I came

To that time when there was neither

Form nor color

Key collaborators

One-off collaborations have offered Haino the chance to dip his toes into many various waters over the years, and several have then spiralled into longer-lasting musical partnerships. Tatsuya Yoshida of Ruins has played with Haino in several iterations, including rumbling acid jazz trio Knead and the unpredictable Sanhedolin (which featured Haino playing flute), with only Merzbow as a rival when it comes to the collaboration game. He has made albums with Boris, Pan Sonic, Peter Brötzmannm, Zeitkratzer, and many more – the list honestly goes on for far too long to include here. In most cases though, it’s Haino’s persona that takes over. Only the duos with Derek Bailey, Loren Connors, and perhaps Merzbow can really be said to have been equal collaborations.

An annual meetup with Jim O’Rourke and Oren Ambarchi has become one of his more interesting recent projects, the trio recording an album a year since 2010. Haino still inescapably dominates (both O’Rourke and Ambarchi are of course Haino super fans), but we get to hear a totally different side of both Ambarchi and O’Rourke as instrumentalists rather than the composers and technicians they’re best known as. Ambarchi also plays drums in Nazoranai, a power trio with Stephen O’Malley on bass plus Haino at the front.

The Marc Jacobs’ Fall/Winter Campaign 2016

Somehow, Marc Jacobs got switched on to Haino, and in 2016 he invited him to make music (and get his photo snapped) for the Marc Jacobs Autumn/Winter Runway show. His music for the fashion show featured almost nothing but the gently overlapping jangling of sparse bells, something Haino’s deployed live in concert with Fushitsusha on occasion and forms the backbone of the aforementioned acoustic percussion record, Tenshi No Gijinka. The effect is haunting in the below clip available on YouTube, but the stomping of boots and snapping of cameras have been sadly eradicated. The outfits in the show are themselves very Haino-esque too, all dark and dreary as if designed for someone dressing for a date with a black hole. As far as I can tell Haino’s never been explicitly against commercial use of his music, so it would seem odd to criticise him for the Marc Jacobs thing. One just presumes the opportunity never came up.

Keiji Haino plays as part of the Samizdat event at Selfridges on Friday September 1 alongside KK Null. Click that link to find out how to get tickets. He also plays Supersense in Melbourne this weekend and Le Guess who in the autumn