Glenn Gould, deceased Canadian pianist extraordinaire, is just the kind of oddball character I like and I have taken his records to my heart. In that, I’m far from alone – he was a huge star and a big-seller, and he managed to achieve that Holy Grail in music of having broad appeal and critical respect. “Stolid, grey, unimaginative, eccentric,” he said of himself, with typically self-deprecating humour. More accurate is a famous quote by the great Hungarian-American conductor George Szell: “That nut’s a genius.”

Inevitably, Gould’s quirks – mumbling in the background on his albums and playing at tempos that he thought correct, regardless of a composer’s wish or orders – earned him detractors, some of whom assumed he was being intentionally bonkers, possibly for marketing reasons. But Gould believed that “the only excuse we have for being musicians and for making music in any fashion is to make it differently – to perform it differently, to establish the music’s difference vis-à-vis our own difference”, and he hated the fact that he involuntarily hummed along when he played, saying: “It’s a terrible distraction; I don’t like it. I would resent any artist whose records I bought indulging themselves that way and I don’t see why anyone puts up with it.”

There are also plenty of people who do like his records but get annoyed by the fascination with what is often termed ‘the cult of Glenn Gould’. But, as we’ll find out, it’s near-impossible to separate Gould’s music from his myth. Some of his most freakish qualities, like his extraordinary memory and hypochondria (and the chronic self-medicating that went along with the latter), ultimately provide as many clues to his style of music-making as the tapping exercises he did to help his fingers operate more independently from his arms, like he was training a brain in each fingertip.

Gould, who died of a stroke aged 50 in 1982, endures because he’s constantly coming into better focus. Despite his fame and the sheer amount of himself he put out there (over 60 albums, millions of written words, radio documentaries, even comedy skits), he was an intensely private man that we now know a lot more about, as a seemingly endless stream of biographies and documentaries emerge. We realise today just how ahead of his time he was, foreseeing a future for music production that looks not unlike it does in 2017; more democratic, less ivory tower, with technology driving the revolution. Unlike almost every other star pianist of his era, he hated the concert hall and adored the studio, and he spoke in the 1960s of mail-order “kits” becoming available that would allow anyone interested in music to “do it themselves, and be in a sense your own editor, your own performer”.

What Gould was suggesting was actually quite unorthodox – the idea that the listener could splice together different bits of recordings to “assemble” something that was most meaningful to them, and as such he would have loved Pro Tools, Garage Band, the internet, and probably even social media, for a different reason. At the heart of his dramatic decision to quit live performance in April 1964, aged 31, was a growing obsession with control – of his music, but also his image. It’s not much of a leap to imagine Gould using social media with as much imagination as he used a recording studio. “You just focus on the different ways he presents himself – there’s no end to the interest,” philosopher/writer Mark Kingwell says in 2010 documentary Genius Within: The Inner Life Of Glenn Gould. “Why do people all over the world find themselves drawn to Glenn Gould? It’s not just because he’s a great player, it’s because his life is itself a performance that people can’t take their eyes away from.”

Listen to A Consort Of Musicke… here

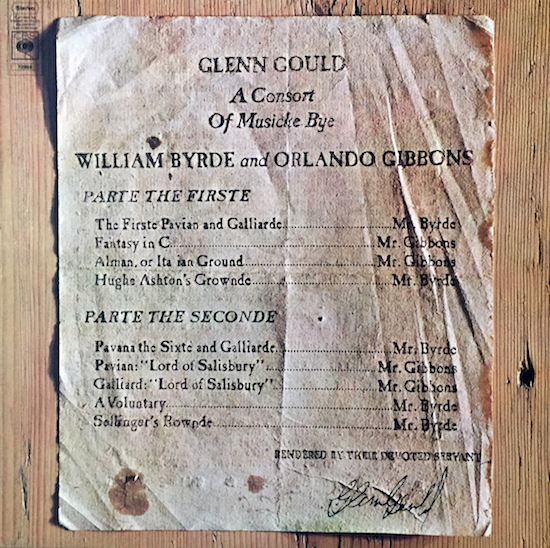

This album, with its amusing olde-worlde title of A Consort Of Musicke Bye William Byrde And Orlando Gibbons (the bottom of the cover says: “Rendered by their devoted servant Glenn Gould”) isn’t one of his best-known, but I’ve picked it for a number of reasons: it’s supernaturally beautiful; I bought it for a quid in a charity shop, which is the point of this column; it’s the best introduction I know to Gould’s unique brand of musical alchemy; and he loved it, once saying it was “the best damn record we’ve ever made”, rivalled only – he believed – by an album of Prokofiev and Scriabin sonatas that he released around the same time (that one in 1969; this one in 1971, but parts were recorded in 1967-68).

Now, you could do well to take some of what Gould says with a pinch of salt, including his outburst of, “I detest audiences – not in their individual components, but on mass I detest audiences; I think they’re a force of evil” (he meant concert audiences, not the buyers of his records), but I’ve no reason to suspect that this wasn’t his favourite record, nor his assertion that Orlando Gibbons, an English musician of the Elizabethan period, wasn’t his “favourite composer – always has been”, as he also said. It only jars with the public perception of Gould because he became so well-known for his stunning playing of Bach that his recording of ‘Prelude and Fugue No.1’ from the second book of The Well-Tempered Clavier (complete with background mumbling) was included on the Golden Voyager Record that was launched into space in 1977 for alien lifeforms to discover and enjoy.

A Consort Of Musicke Bye William Byrde And Orlando Gibbons also finds Gould at a fascinating, furtive moment in his life. He’d broken through aged 22 in 1955 after making an entirely leftfield decision to record Bach’s then-obscure, very cerebral Goldberg Variations as his debut album (a mainstay on lists of the best classical records of all time), then he became globally famous in 1957 when he toured Russia at the height of the Cold War. He played flat-fingered and very low on a battered adjustable-height chair that his father made him (as he would do for the rest of his career) and he intrigued people. He befriended and collaborated with the cream of American talent, including superstar conductor Leonard Bernstein, and there’s wonderful film called On The Record made by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) that catches a dashing Gould during those heady days – recording Bach’s Italian Concerto in New York in 1959.

But here’s the thing with Gould – he always went back to Toronto, the only city he claimed he could feasibly live in. It suited him to be away from high society, and it’s no accident that after he quit touring in 1964 he exploded with creativity, releasing five albums in 1968 alone (although one was an interview record) and also working with the CBC on a run of abstract, forward-thinking radio documentaries, some of which he called “contrapuntal” – a musical term describing independent melody lines playing simultaneously, just like you hear in Bach. Gould did the same with speech, so you hear two or more voices talking over each other on a theme, like ‘The Idea Of North’, the first in his Solitude Trilogy.

This wasn’t usual. I don’t know of any other musician who took what they learned from Bach and applied those lessons to making speech radio, but he was fascinated by the medium – “One can make a statement about the human condition, by virtue of the way in which you can define it through using the human voice,” he said – and even used it to briefly dip his toe into the world of pop. Perhaps the most random project he ever completed was a straight-ahead, by Gould’s standards, 1967 radio piece on English singer Petula Clark, who he’d hear while driving his car (usually like a maniac, reportedly) and seemed to have some kind of very remote crush on (they never met).

He was wide-eyed and alive in the late-60s and it later emerged that Gould – suspected to be gay or, more likely for a man who hated to be touched and never shook hands, asexual – was in love. In Los Angeles in 1956, he’d met German-American composer Lukas Foss and his artist wife Cornelia, and the three of them had become close friends – talking on the phone, his preferred method of communication, usually late at night. Many years later, in 1967, Cornelia left Lukas to be – along with her two children – with Glenn in Toronto, describing their relationship as “among other things, quite sexual”.

Here’s what Cornelia said about Gould’s recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. “What Glenn had done is taken the piece metaphorically, cut it apart and put it back together in a very strange way – as if he was doing the same to a clock. It still made sense, of course, but it made a totally different kind of sense.” Put differently, he managed to make very old music sound bracingly modern, just as he did on A Consort Of Musicke Bye William Byrde And Orlando Gibbons, which he began recording soon after Cornelia moved to Canada. And you sense this complete clarity of purpose and sound the moment he rolls his fingers across the keyboard on the album’s first track, William Byrd’s First Pavan and Galliard, composed in the late-1500s.

A Consort Of Musicke is a sublime, profound record and it’s very much a record – a perfect example of what Gould was capable of achieving in a then-modern studio. I think it has a special place in his back catalogue, above and beyond his love for it. “I can’t think of anybody who represents the end of an era better than Orlando Gibbons does,” Gould once said of a composer, who died in 1625, 60 years before Bach was born, and this album seems to represent the end of something for Gould, too. By the time it came out in 1971, his relationship with Cornelia was in trouble – she returned to her husband a year later – and although he’s thought to have fallen in love again with the Ukrainian-Canadian soprano Roxolana Roslak, with whom he also recorded, he seemed more at sea in the 1970s than he was at any other point in his life.

Gould, who it’s worth noting is now suspected of having suffered from Asperger’s Syndrome, had a quip about his drug use: “One journalist wrote that I travelled with a suitcase full of pills. This is grossly exaggerated – they barely fill a briefcase.” For a private person, he was surprisingly candid about pill-popping, saying in the 1968 interview album he released, Concert Drop-Out that he only went to concerts if he couldn’t hear the piece of music on record or the radio. Then, “I’ll take a tranquiliser, which will sedate me sufficiently that all my traumatic hang-ups… will disappear for an hour or two.” He was a ‘doctor shopper’, securing prescriptions from numerous different GPs, and the sheer amount of drugs that he took inevitably had consequences. By the 70s, his good looks had vanished; he was notorious for always wearing a winter coat and gloves, even in summer; and it’s thought he was once arrested in Florida, accused of being a vagrant.

Cornelia Foss said that Gould had a psychotic episode within two weeks of her moving to Toronto to be with him, and she left in 1972 because he became increasingly paranoid and eccentric. He was obsessed with his health, keeping a constant log of his blood pressure and refusing to see his dying mother in hospital for fear of picking something up. And that obsessiveness extended to all parts of his life – his work, and to how he was perceived in public.

In the Genius Within documentary, his biographer Kevin Bazzana says, “There was no question that Gould’s obsessiveness had serious downsides. After he quit concert life, he really was unwilling to say a word in public that wasn’t scripted.” The Concert Drop-Out interview record was carefully curated, and it’s not even his weirdest album. In 1980, celebrating 25 years of being a Columbia Records artist, he put out a double LP called Silver Jubilee. The first disc is a “grab bag” of unreleased recordings; the second a comic play/fantasy about Gould’s “hysteric return” to the concert hall. He voices most of the characters himself – old alter-egos of his like the pompous English conductor Sir Nigel Twit-Thornwaite and Dr. Karlheinz Klopweisser, a German composer and critic – and, at 54 minutes long, it never seems to end.

Was Gould going off the rails? Some people certainly thought so, not least when he announced he was going to re-record his most famous album, Bach’s Goldberg Variations, in 1981. It stunk of a gimmick, but only a fool would have dismissed Glenn Gould. Where the first recording is frantic and exhilarating, clocking in at 38 minutes, the second one is ghostly, 12 minutes longer, and almost unbearably moving. It wasn’t his final album, but it wasn’t far off, and he almost certainly knew it was bookending his career.

In 1962, Gould said: “The justification of art is the internal combustion it ignites in the hearts of men and not its shallow, externalised, public manifestations. The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenaline but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.” It’s a lofty statement from a man whose own art is actually very accessible and approachable. And although he was distant and strange, he hasn’t been remembered as such by fans of his music. He did more than perhaps any other musician of his generation to scrub classical music clean of the fustiness that ruins it for so many, and he still does that. There have always been plenty of wonderful personalities and wackos in classical music, but no one quite like Glenn Gould. He looms higher and higher – a bigger figure in death than he was in life.