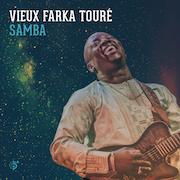

Samba – not to be confused with the Brazilian dance music – is from the Songhai meaning for "second born," as well as "good luck," making it a fitting appellation for the latest album by Vieux Farka Touré, second son of Malian blues guitarist Ali Farka Touré.

While Touré has been far from quiet over the last few years, Samba is the first LP released under his own name since 2013’s Mon Pays. In the time since he has collaborated with Israeli singer-songwriter Idan Raichel, as the Touré-Raichel Collective, who released two LPs together – 2012’s The Tel Aviv Session and 2014’s The Paris Session. More recently he worked with Julia Easterlin on Touristes in 2015.

The recording of Samba took place in front of a live audience of around 50 people for the Woodstock Sessions, in Woodstock, New York. The session had originally been planned as a live run-through of existing material, but after the original date was postponed, Touré made his visit the following year in 2016 with the all-new set of songs featured here. The live setting suits Touré’s guitar playing as his mastery of the instrument unlocks hidden musical sequences. In live performances Touré induces a trance-like effect on audiences, and there is space on the tracks here to unravel intricate tapestries of sound. While the energy of the live show is captured, this is clearly a studio album, with no audience applause from the onlookers (although whether or not they were able to sit still in their seats has not been disclosed).

Touré has been called the “Hendrix of the Sahara” and the solo and feedback playing on ‘Homafu Wama’ showcases the kind of axe abandon that Jimi would be proud of, complete with hard rocking breakdowns. A chorus of backing singers (from the crowd) solemnly chants a repetitive refrain as Touré ad libs his vocal lines. The impassioned performance fired up by the song’s subject matter, addressing the invasion of northern Mali when musicians have been targeted in recent years.

Following Ali’s death in 2006, Vieux launched his own solo career, with a self-titled album in 2007. Working with other artists recently highlighted his ability to adapt his playing style to different musical environments and disciplines, much like his father’s work with Malian kora player and griot Toumani Diabaté. The recordings on Samba represent a return to Vieux’s otherworldly Malian blues playing – continuing, in his own style, the rich vein of sounds that his father was renowned for.

While one of the great strengths of Ali’s music was finding sounds to fit in the spaces between regular song structures, Vieux’s approach is perhaps more direct – letting fly with dazzling finger-picking guitar technique. The instrumental ‘Bonheur’ opens the album, with progressive open ended guitar licks around a steady rhythm, Touré finding those spaces and rocking out.

On Samba Touré is backed by bass and drums, with traditional Malian instruments, including calabash and shaker percussion, and ngoni, with a cast of 12 additional musicians appearing over the 10 tracks. Among them is a reunion with Raichel, who plays keyboard on two tracks, ‘Mariam’ and ‘Maya’.

On ‘Mariam,’ Touré sings over a rising melody that builds as his guitar lines develop into ever more spiralling directions, over the smooth lilting backing, the song dedicated to Peule women of Mali and “all the sisters of the world”. ‘Ba Kaitere’ nearly spills over as the track seems to subliminally speed up, with Touré’s phased guitar leading the charge, the rhythm section doing all it can to keep up, in non-stop drum fills. At other times the group insert big beats to highlight peaks of barely contained guitar playing. When singing Touré raps his lines, and like his guitar playing, lines overlap.

On slower tracks, like ‘Samba Si Kairi;’ (a reworking of a song Touré’s grandfather used to play him), ‘Maya’ and album closer ‘Ni Negaba,’ Touré can reign in the excesses and produce delicate patterns and express a deeply soulful vocal delivery, as in the griot folk tradition. But for the most part Touré updates those sounds, with effects-laden electric guitar and full rock band backing.

Touré also explained that “samba is one who never breaks” and on Samba he has returned to uphold the majestic grace that made his father’s music so compelling. Within the traditions of the music he is playing Touré continues to develop his own sound world.