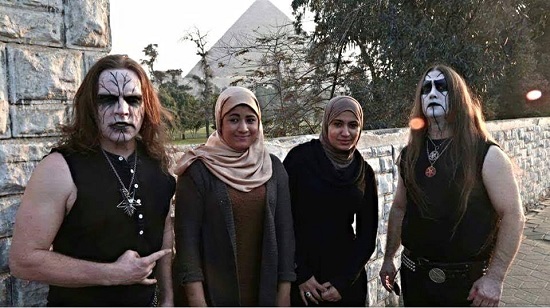

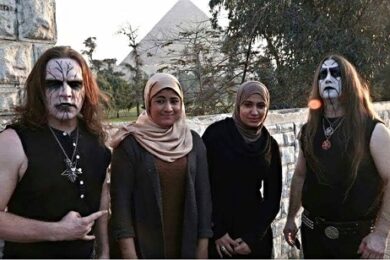

Inquistion in Egypt, image courtesy of Nader Sadek

"Satanist", to them, equals homosexuality; killing cats and drinking their blood …"

"Suddenly, in front of me, hell broke loose. It was bad. So bad … They are hitting you everywhere and they are pushing you in every direction and they had dogs … People started to faint and I thought it to be wise to throw yourself under a pile of fainting people. Play dead! Play dead!"

‘Omar’, speaking to the writer Benjamin Harbert about his internment as a "Satanist" in 1998.

EGYPT – 1996/1997

At 4am on 22 January 1997 armed Egyptian state police forcibly entered the homes of about 100 young people, including – according to one source – a 13-year-old girl, and arrested them. They were imprisoned for up to two weeks. According to one, who wishes to remain anonymous, they were beaten, sexually abused, attacked by dogs, and left isolated for extended periods. Their crime? They were accused of Satanism, of "dead cat blood drinking, sex orgies, insane drug use."

A group of Islamist extremists who were also being held were informed they would be sharing their quarters with the "Satanists". That caused a riot so severe that the "Satanists" were transferred to another jail. "We started to hear shouts from far away. Shouts, screams from a faraway place …" one victim remembered, speaking under the pseudonym Omar to the writer Benjamin Harbert for his essay on the events, Noise And Its Formless Shadows, compiled in the book The Arab Avant-Garde. "We realised that the sounds of the screams of the night were because the Islamists of the same prison were told that the Satanists were in the same prison as them, and they decided to revolt … they wanted to kill us."

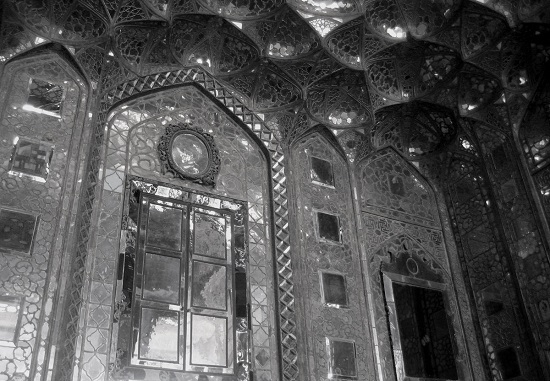

Omar’s real crime, and the crime of nearly 100 of his friends, was not Satanism. It was a love of heavy metal. Egypt’s metal scene had been in rude health the previous year. Metal in Egypt had been no more than a cult in its infancy, sustained by bootleg culture until the advent of satellite TV. By 1996 metal had become a mainstream force in the nation’s musical fabric, with all manner of satellite, experimental scenes. Young fans would congregate in bars like Khaled Madani’s Doom Club, and at the Qsar al-Barun ("The Baron’s Place"), an abandoned villa in Heliopolis.

In November 1996, however, the Egyptian tabloid Ruz al-Yusuf, received an anonymous fax, detailing supposed ‘satanic rituals’ on the outskirts of Cairo and Alexandria, sparking media outrage and prompting a hysterical fear of metal culture in Egypt. On 9 December, Ruz al-Yusuf printed a ‘call to action’ against metal, which led to the arrests a month later. As one fan tells tQ anonymously: "The stories – whether real or not – did shock society (and our mothers). Unlike South-East Asia and South America, Egypt had no rock history, so no one knew anything about rock & roll traditions and excesses. Facepaint, blood and Satan was quite shocking for society. The crackdown happened and that was what all the media spoke about for two weeks. I still think it was ridiculous, though I’m not denying how traumatising it must have been to whoever was arrested."

One particularly melodramatic newspaper account, cited in The Arab Avant-Garde read: "Children had swapped beer and whisky for the blood of cats and pigeons and been tattooed with skulls and other symbols of the occult … Hard rock was played as the fans dug through the graves in search of human bones that could be ‘gifted’ to the devil."

There were other, more sinister reasons for the crackdown. As Harbert explained: "It was a political strategy that had nothing to do with metal or even Satanism directly. The government needed a distraction from two issues: the rapid privatisation of the public sector (initiated by Mubarak’s sweeping cabinet changes) and the intensifying criticism from exiled and imprisoned Islamic extremists accusing Egypt of being anti-Islam. Interior minister Hassan El Alfy became a national hero through his involvement with this crackdown on metal, though none of those arrested were ever convicted of a crime …

"The government’s brutal crackdown, informed by its high stakes wrangling with radical Islamic groups, was a calculated strategy that held up this group of ‘practising Satanists’ as a straw man against which to redefine its defence of Islam. It also provided a welcome distraction from the radical privatisation of the public sector. The practice of persecuting the metal communities then spread across the Arab world to Morocco, Bahrain and Jordan."

These events were 20 years ago, but the shockwaves they sent across the region remain felt. Two decades on, tQ spoke to a swathe of metal fans and musicians from Lebanon to Saudi Arabia, via Iran, Israel and those in Egypt today, to see how how much – if at all – things have changed.

LEBANON – BLAAKYUM

The leader of Lebanese thrash metal outliers Blaakyum, Bassem Deaibess, sees parallels between the events in Egypt and in his own career. His band have flown the flag for the nation’s fertile metal scene for more than 20 years, during which he has twice been detained by the authorities, first in 1998 and again in 2002, caught in the wake of a similar anti-metal witch hunt. Just as in Egypt, metal fans were demonised by the authorities, and scapegoated to distract the population.

Speaking to tQ before participating in a discussion at Chatham House in London under the title ‘Art As Defiance In The Middle East’, he explains that the health of the metal scene in his home country has its peaks and troughs. "It goes up and down. Before 96 metal was huge; in the 80s during the civil war there were bands – I’d see the pictures, they had massive audiences, metal was just a regular thing you played in clubs. But then in 96 the first witch hunt happened, the whole Satanism and backward messaging stuff."

As in Egypt, these witch hunts coincided with political scandals that needed to be buried. "Every time there’s something going on and you need to distract from what the institution is facing, you need to say ‘oh look at these people’," Deaibess says. "The headlines were ‘Hard rock music and backwards messaging is threatening the safety of our children’, ‘heavy metal and Satanism is infecting our society’, such ridiculous stories. You’d turn on the TV and half of the news would be talking about metal and showing reports about how bad and horrible the music is. They incite mass hysteria and mass fear. When you’re scared of your child being infected by this disease, you don’t pay attention to what laws are being passed. Metal is a good scapegoat because it has all the elements that scare society. Politicians and religious institutions rule by striking fear. You need something that would scare people, and what’s better than people who look strange, with long hair and earrings and headbanging and moshing? It’s so alien in a conservative country like Lebanon. The people are extremely conservative, extremely religious, and extremely superstitious. The problem is not just the authorities, it’s the mentality of the society, the prejudice and the discrimination against anyone that doesn’t look like a regular Lebanese person."

‘Alien’ is certainly the word. When Deaibess was arrested in 1998, the questions he was asked would have seemed comical were it not for the gravity of what was at stake. "This guy with a big moustache sits down and says: ‘So! What do you do when you see a black cat?’ And I said: ‘Well, I pet the cat.’ They would say: ‘But how do you pet the cat?’ and then ask: ‘Do you read The Koran upside down?’ You could make a sitcom out of it." Deaibess got off relatively lightly; he says the band Kaoteon were beaten, stuffed in the boot of a car and faced nine days’ imprisonment after their gig was raided because police believed their then name, Chaotaeon, translated into Arabic as "devils".

But what of the Lebanese metal scene in the years since? The years 2005 to 2010 saw a golden age of sorts, with 50 active metal bands selling out 2,000-capacity venues – not bad for a country with a population of around 4 million. In the years since, the scene has shrunk, but Deaibess says it remains stable, although prejudice still remains. "The worst thing is when you’re walking the street, you see a mother who drags her child away from you and crosses the road – you’re seen as this disgusting person."

That said, as a metal musician in Lebanon today, the scene is relatively fertile. "I like to think we have the best metal scene in the Middle East." There is still ignorance, of course – finding a sound person with the requisite knowledge of the genre to know that the distortion is in fact intentional can be a struggle when it comes to touring – but Deaibess says the metal community is as tolerant as can be in Lebanon’s multi-faith, multi-ethnic society.

"It’s very rare that anyone would ask your religion at a metal event. Of course it has its flaws, but the metal scene in Lebanon is the least sexist, the most tolerant when it comes to religion, it’s one of the very few communities in Lebanon that’s tolerant to atheists, any sexual orientation, no problem. No one would ever ask you. We did have at a certain point in time a segregation between communities, because areas in Lebanon are separated by religion, but not any more. Our community is very diverse, you have the really religious Christians and the really religious Muslims, the atheists, they’re all together having fun, and arguing too."

SAUDI ARABIA – AL NAMROOD

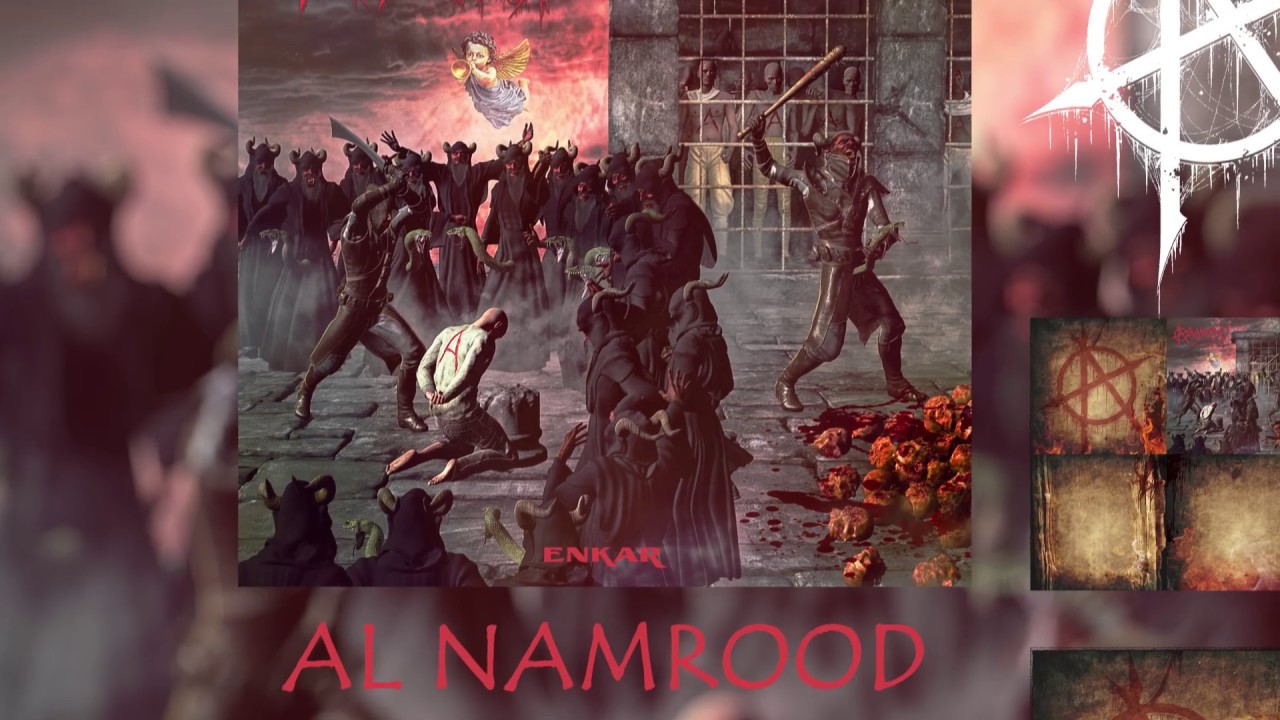

It is a different story in Saudi Arabia. Al Namrood, whose utterly uncompromising and utterly brilliant new album Enkar was released in May, are the country’s only black metal band, one of the most intense musical forces in the world, let alone the Middle East, but must remain anonymous for their own safety. Their music takes a fearless stance against the country’s authoritarian regime, and were they to be identified they would be stoned to death or beheaded for apostasy; CDs had to be smuggled into the country as contraband. When guitars need to be repaired, they have to be smuggled out.

A member of the band known only as ‘Mephisto’ spoke to tQ via email. "Metal is a good way of expression in this wretched world," he says, when asked just what keeps him motivated to continue despite the risks. He began playing guitar in 2006, having been directed to the genre online by "anger, hate and aggression" and a need for "intense, meaningful music with a strong vibe". Two years later, Al Namrood began.

"We look at the world as a free hub, where every human being is entitled to choose their way of life," Mephisto says, outlining the group’s philosophy. "This is strongly defied in our society, [because they] fear that freedom is going to break religion. Most importantly, we do not tolerate any ideology to be forcefully shoved into our throat. The prospective is simple: just don’t stay in our way and we won’t stay in yours."

Yet the consequences of pursuing that ideology could be fatal. "Of course we worry, we can never guarantee that we will be safe," he says. They do not face day to day problems and prejudices as metal fans, simply because to give any indication of their allegiances would be a compromise of their life or death insistence on total anonymity. This extends to playing live. "We dont know if we ever will play [live] or just keep Al Namrood as studio project. We have to balance our wishes with the reality, if playing live will take us to execution, then we won’t do it." It goes without saying that there is no visible metal ‘scene’ in the country. If there are any other bands in addition to Al Namrood, they remain utterly isolated from each other. "We keep hearing there are other black metal bands in the area, but we’ve seen none. When we started in the beginning we tried to get close to some various local bands but they rejected us due to our message and context of music."

Despite all of this, Al Namrood’s music remains totally defiant. The video for ‘Nabth’ (which translates as ‘Ostracised’) is a ferocious case in point. The clip makes use of violent, difficult footage, of protests, riots and police brutality from across the Middle East, coupled with close-up shots of their own album artwork where Satanic, bearded figures wield knives and snakes under a sky painted an apocalyptic red, while a caged populace despairs.

Thanks to support from outside the country, Al Namrood have managed to reach a relatively wide audience globally, but to leave the country would be nearly impossible. "Immigration [is] very tight nowadays and the nationalists and conservative parties are becoming more lunatic toward immigrants. The political tension is this world is miserable and as a result, people became more xenophobic at some level. But say it loudly: this earth doesn’t belong to anyone. Wherever we reside we will survive and do what we want, regardless of any obstacles."

ISRAEL – MELECHESH

Melechesh come from Jerusalem, but they are now based in Germany. They are not Israeli or Palestinian, but from a "a small diaspora in Jerusalem of Armenians and Syrians, a very unique situation," as their formidable guitarist and frontman Ashmedi puts it. However with band members all over the world, and a high profile in the world of metal – they are signed to Nuclear Blast and play to crowds of tens of thousands – they prefer to think of themselves as being from planet earth; Jerusalem is merely a point of origin.

That said, the region still bears its influence in his work. The mythology of Mesopotamia, in particular, though appropriated often by other bands, makes its presence felt – stories of the occult, the beginnings of man, and even pseudo-scientific conspiracy theories of ancient aliens revered in the region as gods, reinterpreted within the genre. "We are Armenians and Syrians," Ashmedi says. "A lot of the mythology from the region, the Sumerian, Babylonian, that is our mythology. A lot of bands around the world always toy with those kind of ideas or use a band names from a deity. We have our great, rich culture, and we might as well dive into it and represent it musically."

That’s not to say that Melechesh want their background to be used as a mere promotional device. "We want to be responsible and make sure it’s quality [music]. We don’t want to be relying on it as a gimmick. We also want to have a credible approach to your music that is accessible to people: they don’t know why they like it, it just sounds good, and not a one-trick pony. That’s what we set about doing, and now we’re an internationally recognised band with good sales, and insane concerts and festivals and tours, and I’ve made my living off it basically for the last 11 years."

The popularity of metal in Israel, and the fertile ground in which Melechesh made their name (they were the first non-Jewish group to get signed there) is also down in part to collapse of the Soviet Union, which saw a mass migration of around a million Russian Jews to the country as they were finally granted permission to leave Russia and the other former Soviet republics, many bringing a love of metal with them.

As for the modern politics of the region, there might be allusions and parallels drawn between the myths they delve into and the present day – ‘Lost Tribes’, for example, on the band’s 2015 record Enki, can be read to have "a lot to do with Isis." However, Ashmedi is keen to point out: "Until [the West] find a new great villain away from the Middle East, it’s going to still have negative connotations. Maybe 20-30 years it’s going to be the nicest place for them to go make movies where they are the allies, not the villains.We don’t play the game of politics, we transcend it. As a self-thinking person I have my opinions but I do not discuss them. The band Melechesh transcend that. We talk about the cosmic stuff, we show the beauty, the magic, the spice of the Middle East. All you see on TV is women’s abuse, religion and war, and oil. Always negative stories, from the cradle of civilisation. There’s so much more good than bad there, so I want to show that with the art."

On occasion, however, Ashmedi has been been caught up in the familiar cycle of sensationalised Satanism. In 1995, when they were still based in their home city, the demo release that saw them make waves in Israel’s metal scene, As Jerusalem Burns (also the title of their debut album the following year), caught the eyes of the tabloid press. "We were approached by a big newspaper, and they used the headline ‘A Satanic cult is existing is Jerusalem.’ We were shocked. The authorities were suddenly interested in meeting me, but Ashmedi is my stage name so they couldn’t find us. The newspaper at least did say ‘They didn’t kill anyone, we’re not giving you their information.’ However, the police then started arresting a lot of metalheads, so we kind of laid low. I left the country for a little bit, for two months. When I came back, they had much bigger problems – they forgot about us."

Once or twice the band have found themselves caught in the edge of the region’s conflicts. Ashmedi remembers a bus exploding above the band’s basement studio. They were playing so loud that they didn’t hear it, only to emerge four hours later to dark, empty streets and worried families. "It was the 90s, lots of buses had been blowing up," Ashmedi says. "It was 50 metres away from us that the bus blew up, and my mum had seen it on TV. All our parents were freaking out, because they closed the road, and there’s no phone, nothing, we were busy playing music. We went out four hours later and it was dark. We just saw a couple of police cars and they’re cleaning the street, as if nothing happened."

In 1998 Melechesh relocated to Europe, first to the Netherlands, and then to Germany, although Israel for the most part was not an intolerant place to be a metal fan. "Israel is quite liberal to the Israelis, and to the Westerners," Ashmedi says. "Tel Aviv is one of the most liberal places in the world, and in Jerusalem there are liberals as well as the religious people. In West Jerusalem where the Israeli and Jewish communities are, if they see a headbanger they don’t care about it. They see anyone who’s not a Hasidic Jew as not a Hasidic Jew, they don’t see it as headbanger or not headbanger. And the liberals, they don’t give a shit. In East Jerusalem, in the Arabic side, [metal] was new because there wasn’t any headbangers there, so when I walked there with long hair with spikes and stuff they looked at me weirdly. But then [also] they knew I’m the foreign guy, the Armenian-Turkish guy."

Things have improved further still, and an underground metal band can draw a healthy crowd of 100 or so depending on their network, which this in part is thanks to Melechesh’s status as trailblazers of the genre. "People are now actually proud of us, and in a Palestinian Time Out magazine Melechesh was the first artist of the month to have been been black metal." That said, as Ashmedi points out, Israel is "a very controversial, unique place, and I’m not a spokesperson or an ambassador for Israel. There’s multiple societies in one country, and it differs [from one society to another]. If you’re in East Jerusalem there’s a few rockers but not one CD in the shops or anyone playing any rock songs, it just doesn’t exist. If you’re in West Jerusalem, it’s still a niche but there are one or two rock bars that occasionally play metal. In Tel Aviv there’s a couple of international bands playing there."

It was the practical benefits of moving to Europe rather than any drawbacks in Israeli society that prompted their relocation. "It’s more fun being in Israel, like in Tel Aviv or something, because people are more social and there’s a buzz there, but also there’s less facilities. In Germany it’s the metal centre of the world, it’s part of their DNA, you see metal music on commercials. In Germany it’s part of the culture; in Israel it’s just a unique subculture."

IRAN – AKVAN

In Iran, a musician known as Vizaresa wants to alter unfair perceptions of his country through his singular project Akvan. His focus is on the pre-Islamic, Zoroastrian Iran, using traditional instruments as part of a claustrophobic, uncompromising breed of genuinely terrifying black metal, drawing on the rich landscapes and deep Persian mythology of the area. The name Akvan comes from the name of a demon in the Shahnameh, the national epic poem of Iran, the antagonist of the god of Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda.

Before the Islamic revolution of 1979, Vizaresa’s parents left Iran for the United States, where he spent a childhood enraptured by the power of heavy metal. "It moves me in a way nothing else can. For me, listening to metal is a very visceral and emotional experience. I am inspired by other forms of music, but metal is something different altogether. In the same vein as classical Western or [traditional Iranian] Sonati music, it’s just so much more epic and intense. It’s difficult to express in words. The lyrical content often deals with confrontational topics that require and encourage individual thought."

For the last few years he has been based in Iran, "to gain a better understanding of my ancestral home", and he releases his music via Bandcamp, on a tremendous series of EPs that take on themes like the ancient Persian hero Cyrus the Great. Speaking via email, he expresses a deep love for his country. "I hope to inspire fans and curious passers-by to conduct their own research into the ancient and epic history of Iran. Hopefully, they will come away with a more positive outlook in regard to this beautiful country. They will probably find that the Iran they hear about on their television set is nothing like the real thing," he says. "I would like them to see Iran as it is – an ancient, captivating and ecologically diverse land filled with romance, adventure, amazing people, exquisite cuisine, gorgeous art, a lustrous history, and a culture that has influenced every corner of the globe. For some odd reason, we are taught to judge nations based on their leaders and governments, and we lose sight of the actual people who live there. It’s a shame, really. We have so much to gain from embracing one another, and so much to lose when we reject the opportunity to do so. And I hope my music, a mix of East and West, will serve as a model of what can be achieved when two different and seemingly unrelated elements are joined as one."

However hearfelt his love for Iran, however, in his approach to the ancient past Vizaresa takes a direct stance against the current Iranian regime, and although the stakes are not quite as high as in Saudi Arabia, like Al Namrood he has chosen to remain largely anonymous for the sake of his art. "As any scholar of history would know, Islam is not the original religion of Iran. Just like Christianity in Norway, Islam was forced on the Zoroastrian population through conquest and war. And as a result, our original culture faded, sort of. Although Islam was adopted, the Iranian culture largely survived. Since the thematic and lyrical elements of Akvan promote a return to pre-Islamic Iran, many of my songs are intended as opposition anthems."

He says he has to "play it safe", to avoid repercussions. Being a musician is not a crime in Iran, but "underground musicians, especially practitioners of metal, are automatically associated with devil-worship, blasphemy, apostasy, and expressing anti-regime sentiment. The punishment for these charges if found guilty: death." Working in his public life as a behavioural analyst, helping children and adults with autism, he says he looks like "the last person you’d suspect" of being a black metal musician. "I don’t really talk about my music or personal beliefs outside of trusted circles and refrain from making a public spectacle of myself," Vizaresa continues. "I don’t wear band T-shirts with overt themes of blasphemy and the occult in public. I think it also has a lot to do with my personality and my professional career. Regardless of where I am in the world, I have to maintain a professional appearance."

In Iran, social media websites are blocked. Circumnavigating that with a VPN slows internet speeds to the point where uploading a song onto YouTube becomes an ordeal. Meanwhile any "Western" music has to be acquired from underground bootleg shops, which mostly sell pop and rarely metal. As such, any developing Iranian metal scene is somewhat scattered and stilted. "No bands tour here, local or international. Merch? Forget about it. So yeah, not a real happening place for metal fans," says Vizaresa, who has never played or even attended a live show. The only option for gigs are taken at bands’ own risks in secluded locations – a house party beyond the city limits, for example. "I’ve heard that in the past, certain venues allowed bands to perform without vocals for a few limited shows, although audience members were required to remain seated throughout the performance. This obviously didn’t last long."

As a US citizen, Vizaresa has the option to return to the States and avail himself of regular shows, self-expression, and a chance to capitalise on the waves his work has made in the West. Given the metal scene in Iran is, as he puts it, so "scattered and isolated", it does raise the question of why exactly he remains. "I actually like it here," he says. "I mean, life here certainly has its issues and there are things I see everyday that I am completely opposed to, but the same could be said of the US and most anywhere in the world. The general population, the people of Iran, not the government, are very modern, sophisticated, and hospitable. The culture here is infinitely rich and the streets have a very vibrant feel to them. It also helps that the local cuisine is absolutely delicious. Almost everywhere you turn, there is some historical landmark accompanied by its own myths and legends."

Vizaresa’s is a different Iran, a country defined not by the images of tyranny and repression we’re often shown, but by its ordinary culture and rich history. "It’s actually quite sad and frustrating, because here you have this amazing place, filled to the brim with breathtaking landscapes, culture, history, and a noble people, and on the other hand you have this … stuff … that completely ruins it. I guess that’s why I do what I do. I try to invoke a sense of return to the majesty, to the Iran that was and still can be."

EGYPT – TWENTY YEARS ON

Inquisition, live in Cairo, 2016

In Egypt today, though many remain wary because of the events of the past, for the most part the nation’s metal scene has largely re-emerged. As an anonymous fan puts it: "I really think the state and authorities also have matured and on the contrary would rather have kids busy with riffs, Satan and drugs than politics, no?"

In 2015, however, one member of the scene, Nader Sadek, found himself facing trouble after booking the legendary American black metal band Inquisition for a show. "People watched with jaws on the floor," he tells tQ. "Four hundred people came to the show – it was amazing." He’d had successful shows in the past that had gone without a hitch, both as a performer and promoting bands such as Aborted and Alkaloid, but two days after the Inquisition show there were claims from the country’s Musicians Syndicate about the gig that echoed the sensationalised events of 1997. "[It was claimed we were] all cloaked in stars of David, with a Qatari DJ performing, and together we were worshipping the devil. Of course it was all nonsense." The head of the Syndicate, Hany Shaker, said Satanic music was being brought to Egypt as part of a Western conspiracy to spread "chaos and immorality".

The Syndicate later claimed it was merely concerned that the bands playing did not have the correct permits, but Sadek scored a victory when he appeared with one of its representatives on Egyptian national television. "The hostess was educated and we basically exposed the Syndicate: uneducated, uncultured and inconsistent in their lies," he says. "In an attempt to salvage themselves they said it was a case of missing permits, which made them look worse, as they basically admitted to lying."

Yet in a key progression from the reaction that metal fans received 20 years ago, there was far less public hysteria. "Something quite amazing happened," he says. "The intellectual media came to my defence, and so did [high-profile Egyptian billionaire businessman] Naguib Sawiris. The Syndicate was ridiculed." His battle for what he sees as freedom of expression within heavy metal is far from over, however. Last year, his plans to bring Brazilian metal legends Sepultura to the country were shut down, and Sadek was arrested. He is currently involved in a legal battle with Hany Shaker, the head of the Musician’s Union, whom he is suing for defamation and libel. Worrying, too, is the fact that in 2015 the Egyptian government granted the Syndicate powers of arrest, though some Egyptian musicians believe the practical effect of that is simply to make it easier for the Syndicate to extort bribes in order to let shows go ahead.

HEAVY METAL IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Security staff enjoy Inquisition, live in Cairo, 2016

These interviews cover just five countries, and comprise just snapshots of Middle Eastern heavy metal. It would be impossible to surmise its place among host of nations, each with its own cultural, religious and geographical pecularities. There is no such single definition of a Middle Eastern metalhead – some have endured torture and imprisonment, others risk their lives on a daily basis and must isolate themselves in the extreme for the love of their art, while others lead the way for diverse, accepting creative communities.

The common thread between them all, however, is of utter devotion to their craft, whatever the consequences. There is something about metal as a genre, so often the refuge of music’s true outsiders, that has always bred an extra edge to the dedication of its fans. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Al-Namrood’s insistence to keep risking death for their cause, in the persistence of a band like Blaakyum, for whom another witch hunt could begin at any moment, in Akvan and Melechesh’s defiant promotion of the region’s beauty, history, and above all, people.

Thanks to Bassem Deabiss, Ashmedi, Mephisto, Vizaresa, Nader Sadek and those who wished to remain anonymous for agreeing to their interviews, to Nuclear Blast Records, Against PR and Tom Brumpton PR for helping to arrange them, and to Benjamin Harbert for his invaluable work on Egypt.