The problem with the chronicling of popular music is the temptation to compartmentalise. Rather than focus on nuances and the many shades of grey that colour the world, narratives tend to take sides. And as an event fades into the distance, the neat packaging of its story becomes a convenience. The simplification of history leads to an unquestioning orthodoxy that gets viewed as fact.

One of music’s biggest myths is that punk rock swept all before it like a tsunami, a cultural Year Zero that rendered all that had come before it obsolete. That is obviously nonsense, but what punk did do for a generation within a generation was to reset the musical clock,offering a new set of opportunities that, in turn, mutated into something else entirely.

Looking back at that period, Killing Joke bassist Youth tells tQ: "Punk happened as a frustrated reaction to the pomposity and bombast of stadium rock. The architects of that – Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood and Jamie Reid – invented a whole new vocabulary and whole new visual aesthetic. It was pure rock & roll but at the same time they deconstructed it and made it into something fresh and different.

"That burned very fast and furiously and it was over in a couple of years and what followed was post punk. That took the energy of punk but fused it with disco and funk and all kinds of other things including experimentation and psychedelia. If you listen to PiL’s Metal Box, that’s very psychedelic. That’s more informed by Can than by punk, which was inspired by the blues and pub rock.

"What came after that became more artistic and exciting and experimental, and that drew comparisons to the psychedelic era."

While punk did indeed make a lasting impression on those who were touched by it, there were enough influences coming through from the 60s to also make a difference in the early 80s. The passage of time has served to rub out the impact that psychedelics made on the music of the post-punk era, but LSD was still popular and a strange legislative loophole meant that magic mushrooms were legal on the proviso that they weren’t prepared in any way. In theory, picking and eating them at source wouldn’t be tarnished by the threat of legal sanction.

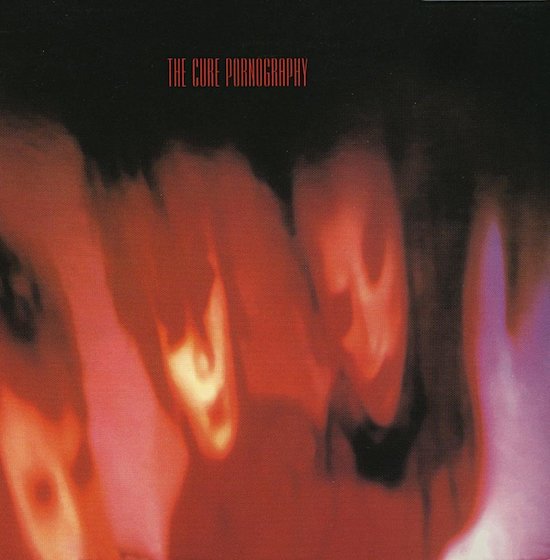

It was in this environment, with the real world issues of the threat of nuclear war and harsh economic conditions also looming, that The Cure – then a trio of guitarist and vocalist Robert Smith, bassist Simon Gallup and drummer Lol Tolhurst – released their fourth album, Pornography. Dark, claustrophobic and densely packed, it unwittingly set a benchmark for subsequent generations while adjusting the vernacular for psychedelic music. Made under the influence of LSD and alcohol and in tense circumstances, it not only concluded a run of albums that had seen the band’s sound evolve over a period of four years, it would also destroy that incarnation of the group.

For Lol Tolhurst, it’s important to understand the filters that helped make that album: "When people think of psychedelia, they think of flowers. This was more Baudelairean in its approach. The way to understand The Cure and the link to psychedelia is that it has to go through the filter of punk. Punk was the thing that changed our whole life. Robert and I were 17 years old when punk hit big.

"I always tell people that Joe Strummer gave me permission to be a musician because up until that point we had no template as to what we could do. Punk kicked things sideways and at that point we knew how to do it. That’s always got to be the filter."

"The early 80s were a very psychedelic time and a lot of people were dropping acid at our gigs," Youth says. "Coming out of punk, the whole spectrum was widening and with clubs like The Blitz and The Batcave, the dancefloor was becoming more of the focus, and people were taking a lot of psychedelics there."

John Robb, fromtman of the Membranes and author of the forthcoming history of goth The Art of Darkness, agrees. "We used to have our own acid tests where we would take lots of mushrooms and put records through their paces," he recalls. "Never Mind the Bollocks … was a brilliant psychedelic record; it was like having a head full of fire. Trout Mask Replica, which is a genius album, of course, was nightmare [when you were] tripping; it was like having your brain tied up in knots."

But what of the contemporary sounds of the early 1980s? "We did test Pornography as well and it was fantastically dense but full of texture which is perfect for tripping; there’s so much to trip you out," Robb says. "Lots of great records are 3D and psychedelia is so much more than paisley shirts and the swinging 60s. Even punk was tinged with psychedelia, and music in the north west of England has always had a trip glow to it. The so-called goth period was laced with the lysergic – it was flipped to the black. I know for a fact that the Banshees were immersed in that world but created an early-80s trip narrative that really suited them, and The Cure had been building up to literally and psychically blowing their minds."

Robb hits the nail on the head when he places Pornography in the context of the contemporary psychedelia of the late 70s and early 80s and the environment in which it was created.

"Pornography is a magnificent record – a stark landscape of a record that, for us, was the Part Two to The Stranglers’ Black And White, another psychedelic record in a then-modern sense that ate into the bleak times but in imaginative musical shapes. We used to love tripping to those bleak landscapes. Joy Division fitted this world as well, and their debut album is a very tripped out work, as was Section 25’s magnificent Always Now."

If the much of the first generation of British psychedelia in the late 60s had harked back to the innocence of childhood, then Pornography was something altogether darker and nightmarish. A world of deception, paranoia and mortality, The Cure’s fourth album is, at times, the sound of abject misery.

For Robb, it was a continuation of a lineage that’s rooted in the darker variant of the psychedelia that emerged from the other side of the Atlantic in the 1960s. "There’s so much crap talked about hippies and the Year Zero of punk but it all merged really; it was the counter culture but with a sharper edge, and more in a 70s focus," he says. "I’m not sure how much peace and love there had been in the 60s anyway. Every band from that time always claims they were the ones who defined peace and love, but the music in the late 60s had darkness and violence around it. The Doors, The Velvet Underground and The Stooges were all in the same spirit as the period we’re talking about, and in many ways The Doors were the alpha ‘goth’ band – all Baudelaire in leather kecks, romantic poets dressed in black. Looking back, punk didn’t end this stuff – it sparked it into life again."

"People started to reference the 60s again," agrees Youth. "The Doors were very popular again in the 80s as was The Doors’ biography No One Here Gets Out Alive. Certainly if you listen to The Cure and bands of their ilk, they definitely dabbled with a kind of psychedelia."

Having worked relentlessly since the release of their debut album, Three Imaginary Boys in 1979, the recording of Pornography was made at the end of an intense four-year period that saw them working under a punishing schedule. Opening with ‘One Hundred Years’, The Cure set out their stall. At surface level, the song may well seem like a series of disconnected images thrown together at random but there’s something much deeper at play here. Whether consciously or not, this is a damning critique of the 20th century, a period of time that saw huge scientific leaps while at the same time industrialising the slaughter of humanity. Factor in images of post-war alienation and meaningless existence, and this is an howl of existential anguish that’s fuelled by Robert Smith’s whining and dizzying guitar lines, Simon Gallup’s two-note bass drones and Lol Tolhurst’s relentless drumming. Alice In Wonderland this ain’t.

"Over the period of about a thousand days, we played a show every other day as well as making three albums," Tolhurst recalls. "We were absolutely blasted, really. We operated at that level of intensity anyway as a matter of course because we wanted to feel connected to what we were doing. We were very committed and we were a three-piece. A three-piece is a cauldron of intensity. To me, The Cure is two separate bands; you’ve got the three-piece of which the pinnacle is Pornography and then you have the five- or six-piece band of Kiss Me.

"If you have a bigger band you have not so much of the vision necessarily but you have the opportunity and if one person flags then someone can help and it becomes that much more easy to navigate. But a three-piece is a triangle and my position was to facilitate the communication between [the other two]. In terms of the intensity of making something that hard together, by its very nature, then the emotional intensity is going to be ramped up."

Coupled with this internal intensity was a huge and unrestrained sound – one that dwarfs their previous sonic efforts. And yet it could’ve turned out so differently if they’d have worked with their first choice of producer, Conny Plank.

"Robert and I met Conny at the Fiction offices and we really liked him," Tolhurst remembers. "He was this great, brooding German man who was head-to-toe in black leather and we thought, ‘Oh, he’s a cool cat!’ He’d just worked with Killing Joke and he told us: ‘Sound is a big animal that you have to control.’ We loved all of that."

The collaboration with Plank didn’t come to pass, and instead the Cure teamed up with 22-year-old Phil Thornalley, who had been working as an engineer at Mickie Most’s RAK Studios in London. Thornalley had been recommended by Steve Lillywhite, who had produced Talk Talk Talk for the Psychedelic Furs the previous year, with Thornalley engineering. Between January and April1982, in nocturnal sessions, the collaborators – the band and Thornalley credited as co-producers – got down to the serious business of birthing Pornography.

"We did consciously set out to make something as extreme as we could make it," Tolhurst says. "Phil was pretty far from us in lots of ways but what he respected was the vision."

The vision was both widescreen and hellish. Probably because of his demons, his later role in The Cure and the recriminations that followed his departure, Lol Tolhurst later became a figure of fun, but he made an enormous contribution to this incarnation of the Cure. Central to Pornography‘s sound and vision is his monolithic drumming, be it the relentless and morbidly-paced motorik of ‘Cold’, the bludgeoning woe of ‘The Figurehead’ or ‘The Hanging Garden”s skittering yet hard-edged beats.

"It wasn’t going to be like Scott Walker with us punching bits of meat to make the drum sound, but Phil kind of got what we wanted to do," explains Tolhurst. "He cleared out that huge room at RAK Studios and put the drums in the middle and recorded this monstrous sound."

Thornalley later told Mojo that the Cure drank heavily during the Pornography sessions. Add in the consumption of LSD and the fact that the three band members were spending virtually all their time together – they were living in the offices of their label, Fiction – and the conditions were set for an overwhelming record. "We were living in insanity together 24/7," is how Tolhurst puts it.

"Living like that created a feedback loop that could be productive and sometimes very destructive. I can’t say that we were all that happy or sane when we made it. The emotions running around its creation were pretty intense and for us to live and work together like that was a little psychotic."

Pornography was The Cure’s first masterpiece, and it remains their highwater mark. It is a potent, challenging and, at times, frightening record. "One of the central ideas that we had around Pornography was that what the world around us thought of as pornographic, we didn’t," says Tolhurst. "People’s bodies aren’t pornographic. What was pornographic, to us, was the way that people treated each other and how political systems destroyed people and that kind of intolerance. That’s what we were trying to get across."

That is apparent during the closing title track. A descent into madness and despair, its remorselessly bleak outlook and unyielding execution of information overload is at least offset with the slightest glimmer of hope as Smith yells at song’s climax, "I must fight this sickness / Find a cure!"

In a move that would break the band, the album was taken immediately out on the road before the album even hit the racks on May 4, 1982. The Fourteen Explicit Moments tour kicked off at the Plymouth Top Rank Skating Bowl on April 14, 1982 before winding up at the Hammersmith Odeon in London on May 1.

Music journalist Hugh Gulland caught the band at the Southampton Gaumont on the fifth night.

"A large part of the set was taken up by Pornography material – which I wouldn’t yet have heard on vinyl – so a very dense, near-claustrophobic quality was prevalent," he says. "They had their obvious limits in terms of showmanship but they were able to conjure up something in terms of mood that was just extraordinarily persuasive."

The band’s use of electronics – then still in their infancy – also contributed towards the overall effect. "While ostensibly a guitar band, The Cure had at this stage made electronics intrinsic to their sound," Gulland says. "This was still the period before electronic technology was ‘smoothed off’ – synths and associated devices in these days sounded percussive, harsh and a bit threatening."

Underpinning it all were those unrelenting and brutal drum,s but with them came a sense that the end of a particular road was being reached.

"While Tolhurst would eventually be sidelined from the drums completely, I can’t overstate the importance of his work to this phase of The Cure – those stark obsessive drum patterns were a huge part of the experience," Gulland emphasises. "Seeing The Cure at this period, you did get the feeling you’d been pulled into some emotional vortex, an experience that was both troubling and thrilling. I’m not so sure it struck me on the night so much as when I heard the album a few weeks later, that this must represent the end of something – if not the band, certainly a stage of their existence. ‘I must fight this sicknesss / Find a cure.’ It sounded so final."

John Robb agrees: "Punk and post-punk was intense. Music was often measured in intensity – how intense was that album or how intense was that gig? And that’s a good thing. I love intensity. I want to feel hyper-alive."

But if the audience were feeling hyper-alive, the mood backstage was quickly deteriorating. With no time for a break, they embarked on a tour of the Benelux countries, Germany, France and Switzerland. But relations between Robert Smith and Simon Gallup had taken a nose-dive.

"We came straight out of the studio and straight out on the road and then we stared playing Pornography to people in much bigger places and people weren’t really prepared for it. That became a source of discontent for us," Tolhurst says.

Smith and Gallup came to blows after playing Strasbourg and both immediately headed home. Despite taking three days to cool off, it became apparent to the members of the band that the remaining dates were to be The Cure’s swansong as a trio. But what precipitated the bust-up?

"It was like herding cats and everyone within the band saw what was going on slightly differently," says Tolhurst. "To me, the thing that makes The Cure great is the thing that pulls it apart, and this is encapsulated in something that Simon Gallup wrote to me recently. He said, ‘I wish that when we were younger we’d been kinder together,’ and I absolutely understand that but to make that kind of music it had to be an inferno. And we ended pouring gasoline on that inferno, too."

He sighs. "It was also that classic English thing about not talking about what was on our minds. Instead of talking about what was on our minds, we’d talk around it."

It was little surprise that the despairing Pornography met a lukewarm response from the press upon its release in May, 1982. Stacked against releases such as the bright pop of ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love, the reinvention of Dexys Midnight Runners with Too Rye Aye or Culture Club’s Kissing To Be Clever, Pornography was like the guest who rocks up to a party and spends the night sulking in the corner. But its dubious charms and seductive darkness enticed more and more listeners as the years passed.

"It’s my favourite Cure album and it’s the pinnacle of the three-piece line-up," asserts Lol Tolhurst. "We honed what we could do in that skeletal, bare bones structure and as a three-piece you’ve got to be really good at what you do. You don’t have room to hide and it’s like being totally naked.

"I really value Pornography and unlike the earlier material, I wouldn’t change a damn thing. Everything is exactly as it should be."

Cured: The Tale Of Two Imaginary Boys by Lol Tolhurst is published in paperback by Quercus on June 1