There is a work by Jean Arp from 1927 nestled on a wall, appropriately enough, between two windows, in the present show, The Ends of Collage, at Luxembourg & Dayan in London. Tête(1927) resembles a big white splodge of paint on a board against a black and grey backdrop with an inverted y shape cut out to reveal the bare wall – also white – behind, thereby offering up two kinds of whiteness, two aspects of absence.

Tête is not a collage. But, as the show’s curator Yuval Etgar put it to me, “it does everything that collage does: it cuts, it masks, it reveals, it brings together two worlds.” Pausing before this work as we wander through the gallery before the show’s opening, Etgar quotes Donald Judd: “Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface.” Arp’s 42 x 32cm painted board brings the former into the latter, initiating a chance encounter between the real and its double.

Over the past two decades, it has become commonplace to hear that the cut and paste aesthetic of mashed-up music and found footage film is in some sense constitutive of our times. When I interviewed Holly Herndon in the winter of 2013, for instance, she spoke of “jammed up sounds next to each other. John Cage right next to Rihanna right next to whatever” in an arrangement she described as a “cluster jam” directly related “to web browsers and online experience.” From another perspective, consider science fiction author William Gibson’s contention that, “The remix is the very nature of the digital. Today, an endless, recombinant, and fundamentally social process generates countless hours of creative product … The recombinant (the bootleg, the remix, the mash-up) has become the characteristic pivot at the turn of our two centuries.”

But if we look back another two or three decades before Gibson’s 2005 pronouncement, we’ll find it just as commonplace to hear equally smart people cite the very same set of aesthetic signifiers as defining features of what was then called the ‘post-modern’. Go back further than that and it soon becomes clear that at almost every stage of the development of modern culture, some version of remix, recombination, and re-appropriation has been claimed as a significant feature of practically every art movement since the turn of the twentieth century, whether punk, situationism, pop art, abstract expressionism, surrealism, dada, constructivism, futurism, or cubism. From the moment, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque first took to sticking newsprint and wallpaper onto their canvases, we have been immured by collage, marked on all sides by its frayed edges.

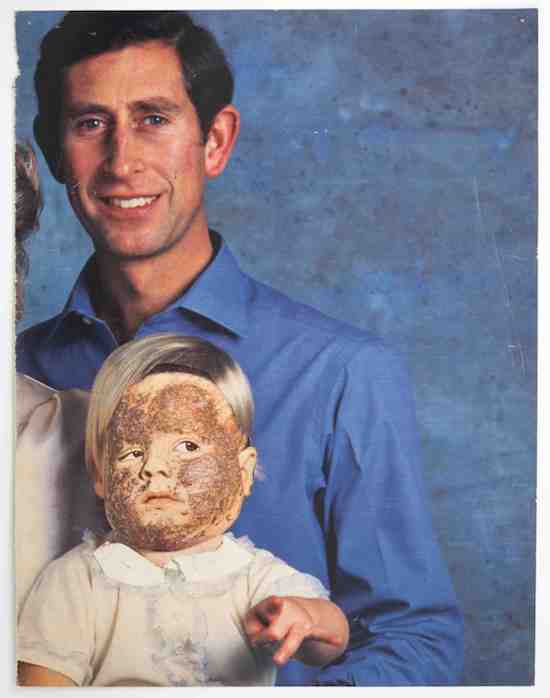

And yet, for Yuval Etgar, collage may have reached its end – or rather, ‘ends’. There is a quite deliberate polysemy in the show’s title: ends as not just ‘conclusions’, but aims, desires, and – crucially – edges. Collage is always an art of liminal spaces, an art of edges, and leaps across those precipices. Many of the artists Etgar spoke to, he tells me, emphasised the necessity of keeping visible and clearly apparent every cut and every splice between collaged papers. Regard Mark Flood’s The Little Prince of 1985: a magazine centre spread of Prince Charles, Lady Di, and baby William, with most of Diana crudely torn off in a straight line and a rough-cut facial disfigurement placed over the face of little Wills. There is no mistaking the jagged outlines of this doubled mask. Trompe-l’oeil is not the point.

Mark Flood (b.1957), The Little Prince, 1984. Collage. 13 x 10 in. (33 x 25.4 cm.) © The artsit, 2017

But if our attention is forever being drawn to the papers and their tears, what of the glue that binds them? It is almost suspicious that a century’s discussion of papiers collés has focused almost exclusively on the papiers to the exclusion of the colle. For Louis Aragon, writing in his ‘The Challenge to Painting’ (1930), it was “not even an essential [aspect]” of the whole procedure. So it made me smile, when, a week after Etgar had first shown me round the gallery, I returned to Luxembourg & Dayan for a panel discussion and a voice from the audience asked, what glue do you use?

“Pritt Stick,” replied Linder, one of the two artists on the panel, cheerfully, unhesitating, before admitting, actually, she tended really to eschew the big brand in favour of cheaper substitutes. Punk rock till the end.

John Stezaker, the other artist sat by her side, was rather more coy about the matter. He finally admitted to simply blue-tacking his montages of postcards and old film stills, before handing them to his assistant to stick firm according to whatever principles were currently being advised by the doyens of art preservation. “It’s changing all the time,” he said with a shrug.

Etgar put it to his panel that something had changed in collage itself, around 1977, Franco Berardi’s putative ‘end of the future’, and more or less the time when both of the artists here sat settled into their practice. For Etgar, a certain nostalgia and melancholia overtakes collage in this era, marked by the shift from the appropriation of contemporary images, straight out of the daily paper, to older materials. Stezaker himself has stuck fairly resolutely to imagery from the 1930s and early ‘40s, just before his birth. Linder, likewise, had tended – though less exclusively – to cut out pictures of a certain vintage. But each remains suspicious of Etgar’s distinction. “What about Max Ernst?” Stezaker pleads.

Ernst, pages from whose Une Semaine de Bonté(1933-34), depicting lion-headed generals and sleeping maidens almost drowning under the wavs that have invaded their boudoirs, are displayed here in glass cabinets, tended – like Stezaker – to select his imagery from the period just before his own fin-de-siècle birth. He perceived, in collage, a means by which to “transform the banal pages of advertisement into dramas which reveal my most secret desires.”

It is the word “drama” that I would like to draw your attention to, here. What Ernst is suggesting is that the act of cutting and pasting produces a sense of performance, of action, and of time.

Linder (b. 1954)Superautumatisme, Grande Jeté XV, 2015. Enamel on magazine page, 101/8 x 81/8 in. (25.7 x 20.6 cm.)© The artist, 2017

“They’re both images to do with movement,” Stezaker says of his preference for film stills and postcards. His works somehow capture a whole process and succession in a single snapshot. The journey is frozen in the postcard; the movement of celluloid in the film still. Somehow, by rubbing the one up against the other, the stilled moment is re-temporalised, brought out of its artificially arrested stasis and put back into motion.

“When I work,” Linder says, “it’s almost as much working with time as it is imagery.” She speaks of the peculiar sense of time travel to be found going through the pages of old Playboys or just reading the names of cakes in 70s cook books. It’s a metaphor that calls to mind Kodwo Eshun’s characterisation in his More Brilliant Than The Sun– repeated, more recently, by Moor Mother – of the sampler as a “time machine”.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the moment Etgar chooses for his end of collage – this end that is not a full stop but a cusp and a border between regimes – precisely the moment when collages in sound cease to be a marginal activity, the work of novelty hits like Buchanan & Goodman’s ‘Flying Saucer’ or quasi-academic research like the musique concrète of Pierre Schaeffer and his fellows, and starts to become something more familiar, more mainstream.

John Stezaker(b. 1949)Bubble III, 1987. Collage. 87/8 x 85/8 in. (22.5 x 22 cm.)© The artist, 2017. Courtesy The Approach London. Photo: FXP Photography

Cut and paste music-makers have been more or less explicit in their acknowledgement of collage as a predecessor. When I interviewed members of the group Negativland three years ago, their Don Joyce was quite clear in his description of their Over The Edge radio show as “cubist broadcasting”. David Toop, in his seminal hip hop book The Rap Attack, declares The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel to be “a devastating collage”.

Linder, too, of course, was as involved in music in the late 70s as she was in sticking papers. In the summer of ‘76, she says to the small audience at Luxembourg & Dayan, “in music there were radical changes going on that were short sharp and spiky … using a scalpel [to make visual art] seemed to fit.” So I was curious how much Stezaker, too, might have been affected by the music of his time. After the talk was over, I found my chance.

He was standing in the main room of the gallery, not far from his own exhibited works, talking to a pair of women from the panel audience. “I thought it was a one-off,” he said of his first stabs at collage. “I never imagined that I would still be doing this, forty years later.” Eventually I found a gap in the conversation, sidled up, and asked him how conscious he had been at the time of the kind of sound collaging that was taking place on the streets of the South Bronx.

“I went to New York in the late 70s,” he told me, “and I met with Richard Prince and I heard this Scratch Music and it was one of the things that persuaded me that collage was worth pursuing.”

So you immediately saw, I pressed, the connection between this music and what you were doing?

“Yes,” he replied, “I did.”

The Ends of Collage is at Luxembourg & Dayan until 13 May