It’s far too early in the morning and the jet lag is kicking in, but Debbie Harry is already dressed to kill. Her form-fitting black outfit incorporates a leather harness detail, and silver studs on the back spell out a clear message: ‘Not My President’.

That Harry is no fan of Trump and isn’t afraid to say so should come as no surprise. Though her band Blondie have long since been accepted into the entertainment mainstream, Harry and co-founder Chris Stein were always highly political people, children of the radical and artistic ferment of late sixties New York, a time when flower power idealism gave way to fighting on the streets while the Vietnam War raged inescapably in the background. Back then, rock & roll and protest were inextricably linked, while the counter-culture automatically embraced art, poetry, underground film and experimental literature alongside music and political demonstration. And although sixties radicalism may have been flawed in many respects, by the end of that decade its proponents were at least starting to recognise what would now be called intersectionality: that the struggles of people of colour, women, the gay community and other oppressed groups needed to be supported alongside the largely white, male, middle-class hippy activists’ demands for peace and autonomy.

"Yes, and with what’s going on now, you try to convey the message that this was just what one did as a young person, to just go to protests and deal with being on the fringes of activism," says Chris Stein, who grew up as the son of radical Jewish left-wing activists and trade unionists prior to attending art school and eventually becoming Blondie’s guitarist. "It was just standard procedure back then. Everybody I knew was involved with something or other on some level, no matter how small. It was different than just going to music festivals."

Debbie: "Something that I think is that if we are going to demonstrate at this point, it should be focussed on a specific agenda or reason. It’s good that everyone has got this idea that they have to stand up, but I think we should have a real reason, just like one single reason, rather than just demonstrating for the sake of demonstrating to prove that people are not happy. That’s good for a start, but to move ahead we need to really pick an agenda, and to march for that is, I think, much more meaningful. In the sixties there was the campaign against the Vietnam War, and that was very focussed, with the anti-war rallies. But the socio-political activism, like make love not war, sort of had a softer impact."

Arguably much of the energy of punk in the US came from seeing how the student-hippy protests were put down with maximum force by the authorities. From the use of tear gas and mounted baton charges at the 1968 Democratic Convention, to the fatal shooting of unarmed demonstrators by the National Guard at Kent State University in 1970, there seemed little doubt that the American government under Johnson and then Nixon saw the youthful counter-culture as an enemy within, to be stamped out at any cost. Many felt that the sudden influx of heroin into America’s inner cities was also deliberately engineered by the government, to steer a naïve drug culture onto a more self-destructive path, while also tearing the heart out of the urban black communities that had recently started to organise and agitate with groups like the Black Panthers.

Debbie: "Well, Chris always felt that."

Chris: "Yeah, the drug wars are certainly aimed at the minorities, of course, if not the drugs themselves. The crackdown on that stuff in America is really fucked. The situation with the prison economy is crazy."

The use of smack was also glamorised, albeit unintentionally, by outsider artists from William Burroughs to Lou Reed. Harry and Stein, who later both had their own dalliances with heroin, were both fans of the beat generation writers and the surrounding artistic culture, and certainly had wider interests than just rock & roll. The biographer Victor Bockris once wrote, "Chris and Debbie are essentially beatniks," and the pair largely agree with this assessment.

Debbie: "I think that’s what attracted me as a kid, to move to New York. It seemed really irresistible to me. And we got to meet some of those poets, which was a wonderful part of our early New York life, or mine, anyway. Chris became quite friendly with William Burroughs and John Giorno, and I loved Gregory Corso. I thought he was the most brilliant person."

Chris: "I also met Brion Gysin once, and Allen Ginsberg a bunch of times. I think we identify with the beat movement to a certain extent, as bohemians, sure."

In 1978 Blondie’s beat credentials saw them play at the New York Nova Convention, a three-day festival and symposium in honour of William Burroughs. Other acts on the bill included Suicide, Philip Glass and Robert Fripp, who had already leant his distinctive avant-garde guitar playing to ‘Fade Away And Radiate’ on Blondie’s breakthrough LP of that year, Parallel Lines. Blondie at this point may have seemed an unlikely addition to such a bill, but as massive mainstream success threatened to drag them away from their punk beginnings, Harry and Stein got to know the forbiddingly experimental author of Junky and Naked Lunch pretty well.

Chris: "Yes, well, we both had methadone in common at that point. And a few years later, when I had that long, protracted illness, I was in Manhattan for a long time and the first place I went after that was to stay with him in Lawrence, Kansas. I was there for a couple of weeks. He was a great guy, a very generous, lovely fellow. I think he got kind of cramped being in Manhattan, after a while. Every time he left the house there would be some guy with a manuscript, so eventually he went back to live in Kansas full time. But we remember him in the Bunker [Burroughs’ notorious windowless apartment on the Bowery] and that whole situation, it was cool."

Debbie: "John Giorno is still writing and he’s so great, he’s such a nice person. He’s a sweetheart. But he must be the only one left."

Chris: "John Giorno did a lot of musical projects that we contributed to, a couple of records that he put together. It’s pretty great to be connected to that era, even slightly."

Another major artistic figure who would have an even greater impact on Blondie would be Andy Warhol. Later on Debbie Harry would be the subject of a Warhol portrait, a kind of official seal of recognition of her status as a great American pop icon. But the band actually emerged from the milieu around Warhol in late sixties, early seventies New York, that included The Factory with its stable of Superstars like Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling and Edie Sedgewick , artists and filmmakers like Gerard Malanga and Paul Morrissey, and of course The Velvet Underground and Nico. Before he was seriously wounded by Valerie Solanas, Warhol’s pop art court was a truly radical mix of transgressive individuals and wild experimentalism that connected the street to the academy. The resulting collision of high and low cultures generated powerful sparks that middlebrow America could never match, and both Stein – who attended the New York School of Visual Arts – and Harry – who originally intended to be a painter, and secured a job as a waitress at Max’s Kansas City, the ultra-hip hangout for the Warhol crowd – were very much drawn towards this world.

Debbie: "It was sort of in my mind that that was the world I wanted to be a part of. I think when I first moved to the city I was hanging out with a lot of people who were painters or sculptors or performance artists. It was a great period, a very interesting time. But as a kid, seeing Warhol occasionally on TV with one of his superstars was totally infatuating. It was great."

Chris: "I saw a whole bunch of them on David Susskind. I must have been about 13 or something. I was very taken with Jackie Curtis, I remember. I thought she was great. But everybody was connected. Everybody in New York had some connection, whether one or two people removed, to Andy. So it was inevitable that you would run into him or people in his circle when you were out and about doing stuff. It was just part of the fabric of the whole New York art scene."

Stein’s high school band even opened for The Velvet Underground in 1967.

Chris: "I was 17, and that was connected with Andy because this friend I grew up with, Joey Freeman, when he was 13 he was fascinated with Andy, so he put on a suit and got into The Factory with a little tape recorder and interviewed Andy for the school paper or something. And after that he became a kind of Factory gopher. He would go out for sandwiches for them or whatever, and when Andy was staying at his mother’s he would go over there and wake Andy up. So he was on the periphery of their whole scene, even though he was just a little kid. And he just came to my house one day and said the opening band couldn’t make it to play with The Velvets, so do you guys want to do it? So we just got on the subway and went up to The Gymnasium. There was a whole series of Velvets tapes that were recorded at that place that are released out in the world. They were there for a couple of months; it was kind of a residency. They were just like practising, there was hardly anybody there; not for us, when we played, or for them. I went back there recently. It was this old Polish gym which is up in the east nineties or something like that."

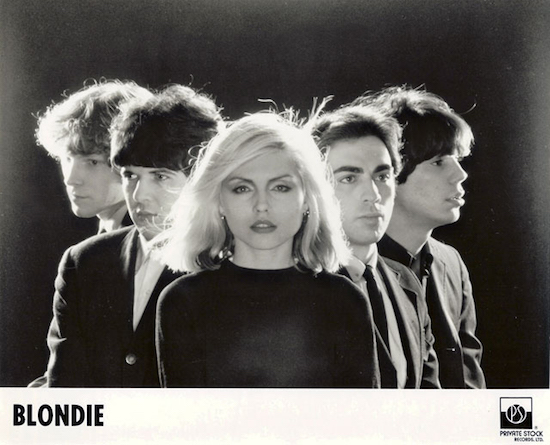

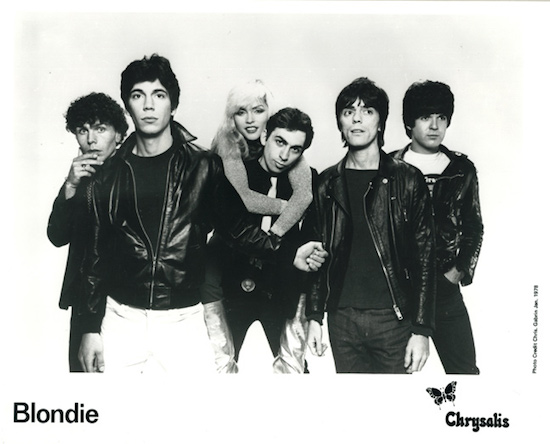

By the early seventies the Velvets’ role as the quintessential New York street band had been usurped by The New York Dolls, who retained a loose connection with the Warhol crowd and Max’s in particular. By this time, Debbie was singing in The Stilettos, an outrageously camp, girl group parody act that also featured Elda Gentile and Rosie Ross. The Stilettos emerged from Elda’s earlier act with Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn, Pure Garbage, and were as much theatrical and musical, with Tony Ingrassia acting as their musical director. Ingrassia was also the director of Pork, a wild theatrical adaptation of Andy Warhol’s diaries that he took to London in 1971, along with Leee Black Childers, Cherry Vanilla and Jayne (then Wayne) County. Elda’s boyfriend was Warhol associate Eric Emerson, an actor, musician and dancer who was also in glam rock band The Magic Tramps, and it was Emerson who supposedly first brought Chris Stein to see The Stilettos. Soon Stein would join the group on guitar, alongside bassist Fred Smith and drummer Billy O’Connor, a combination that would go on to form the embryonic Blondie in 1974.

Chris: "Eric was in Heat and Lonesome Cowboys and Chelsea Girls. He’s got the great bit in Chelsea Girls doing that tripped-out monologue into the camera towards the end of the movie. I saw Eric at the Mercer Arts Centre when I went to see The Dolls for the first time. Eric was opening for The Dolls, and I got close to him and The Magic Tramps. So that was it, before it all connected up. Elda, the girl from The Stilettos, had a kid with Eric."

Debbie: "Chris was living with Eric."

Chris: "Yeah, that was after though, not when I first went to see The Stilettos. That was probably after we had already started doing stuff together."

With O’Connor soon replaced by Clem Burke on drums, and Burke’s friend Gary Valentine replacing Fred Smith on bass when the latter departed to join Television, Blondie maintained their connections with the dragged-up Warhol-Dolls scene. Spotted by New York Dolls manager Marty Thau (who also worked with Suicide and Richard Hell), they were also linked to the Theatre Of The Ridiculous, the shocking, surreal and satirical underground theatre company that celebrated queer culture and which was a pivotal influence on glitter rock, as well as on more mainstream theatrical productions like The Rocky Horror Show. Chris and Debbie maintain that New York’s gay scene as a whole was an important part of their beginnings, with the gay nightclub Mother’s proving as important an early live venue for Blondie as the more celebrated Max’s or CBGB’s.

Chris: "That’s just what we were immersed in. All of those guys were just part of the cultural milieu in New York. It was an important element."

Debbie: "It was a big part of the fabric of the downtown scene, and it always has been, maybe less overtly, but I think it’s always been a big part of theatre, for instance. But it came to stand up on its own."

A crucial break for the band came when Debbie appeared in Jackie Curtis’s play, Vain Victory, for which Blondie provided a live soundtrack.

Chris: "It was just the first act of Vain Victory. It wasn’t the whole play."

Debbie: "It wasn’t actually the Theatre Of The Ridiculous. It was ridiculous, but it wasn’t John Vaccaro, who was the Theatre Of The Ridiculous. It was directed by Tony Ingrassia."

Chris: "The Vain Victory thing was in Tribeca. I remember, because we went there one time with Clem and me in a taxi cab, and Clem opened the cab door into an oncoming car. And when they were giving out their information and they asked him for his name he said he was Joe Dellesandro. I remember that. It was a good moment."

Blondie in 2017 shot by Danilelle St. Laurent

With this melting pot of artistic and avant-garde influences, combining street rock with theatre, art, literature and a high camp sensibility, it’s clear that Blondie weren’t just a garage band. If anything they were more of an art project, taking trashy, pop culture tropes from the 1950s and 1960s and re-contextualising them to subversive effect. Where the hippy era bands had celebrated an often dubious authenticity that actually involved acts of cultural appropriation from the blues and black ghetto life, Blondie took their cues from Warhol and from critics like Susan Sontag, and instead celebrated all that was bright, trashy, instant and artificial. Just as the proto-LGBT culture around them explored the idea that you could choose your own identity and experiment with sexual orientation, rejecting enforced social labels, so Blondie’s playfully aggressive approach to pop was not just some semi-ironic celebration of consumerism but a liberating force. Essentially the group was a pop art project that succeeded beyond its creators’ wildest dreams.

Chris: "Yes, it’s often been described as that within ourselves. We’ve frequently referred to that. There was an element of that, for sure. I don’t know if that implies less seriousness about it. I don’t know if we got more serious about it along the line."

Debbie: "Well, somehow we’ve made the switch from graphics to music or from fine arts or whatever to music, and I think that originally our interests were in slightly different things, although we were both music fans. But it got re-channelled."

Similarly, Debbie Harry’s sex symbol persona was created with a very playful, tongue in cheek intention that was completely overlooked when the band entered the mainstream and her image was taken completely at face value.

Debbie: "Yes, totally. It’s more than fair to say that! Many people don’t like humour. They really don’t, I’m surprised to say, especially in music. They don’t like the idea of combining humour and music."

Even though Harry was clearly a feminist, standing up as a strong woman in a male-dominated industry, her sexualised image (her own creation, but arguably misrepresented by their record company and the media) often worked against her at the time. A poster campaign in the UK, in which a live shot of Harry was captioned with the phrase "Wouldn’t you like to rip her to shreds?" was particularly notorious.

Debbie: "I think we were just trying to survive. In actual fact I think that was always like that. It just grew with time and exposure. But I think there was always a double-edged sword from the get-go."

Chris: "But, you know, sensationalism is inherent. I guess we were also in the early days of sensational advertising with some of that stuff, in spite of it being generated by the record company. With all of those early ad campaigns, nobody came to us and said do you like the idea of this, certainly."

Debbie: "I think that’s just showbiz. Bowie did a lot of things that were like that. It’s always been the goal to be as controversial and suspect as possible. They complained heartily about The Dolls, too, that they were wearing make-up and high heels."

Blondie’s massive international success from 1978 onwards would catapult them into commercial big leagues far from the New York demi-monde they emerged from. With the addition of keyboard player Jimmy Destri, and Frank Infante and Nigel Harrison replacing Valentine, their third album, Parallel Lines, would sell over 20 million copies worldwide. Blondie notched up 11 top ten singles in the UK alone by the time they broke up for the first time in 1982, including six number ones (‘Heart of Glass’, ‘Sunday Girl’, ‘Atomic’, ‘Call Me’, ‘The Tide Is High’ and ‘Island Of Lost Souls’).

Amazingly, throughout this ridiculously busy and productive period, Stein was also managing to co-host a New York public access cable TV show, TV Party, with Glenn O’Brien, on which Harry was also a regular guest. A resolutely DIY affair, the anarchic no-budget, no-script and no-rules variety-cum-chat show was seen by its creators as implicitly subversive, and was introduced each week as "A cocktail party that could be a political party."

Chris: "We did 90 shows. After a while it just became, instead of going to a club, or prior to going to a club, we would meet at the TV station. We’d meet at the Blarney Stone, which was kind of a chain bar, I think. There was a bunch around the city. And then we’d go to the thing, and then afterwards people would go out, but it was a regular thing. At some point we decided that it was best to have it on Tuesday night, because that was the proper distance from the weekend, when everybody would be home and potentially watching it. There would often be 50 people up there, so it was this little sort of regular get together. It was great. It was a really terrific thing. It was so early in the realm of cable television. It was different. It was very punk in its sensibilities. Everybody was on the thing. Iggy Pop was one of the guests on one of the last shows, but there’s no tape of that. It was just up to us to record at home while it was going out live. You put in a cassette with a timer and hopefully it would record. But there are tapes of a lot of the other stuff, with David Byrne and Klaus Nomi and The Clash and so on. Everybody was on the stupid thing at one point or another."

TV Party ran on an exactly parallel line with Blondie’s early success, from 1978 to 1982, and could be seen as a way for Stein and Harry to keep tabs on what was going on in the downtown scene as their growing success inevitably conspired to estrange them from their roots. The show featured No Wave acts like DNA and The Contortions, and in contrast to Blondie’s by-now commercial pop sound, Stein also played in TV Party’s house band, performing improvised psychedelic noise jams alongside band leader, outsider artist and electric violinist Walter ‘Doc’ Steding. Stein later produced an album for Steding on Marty Thau’s Red Star label.

Chris: "Walter’s drummer, Lenny, would play magazines and things like that in lieu of drums. Robert Fripp played with the band a couple of times. I think we’d already sensed the potential of cable TV and this private TV thing, which was also a revelation, because everybody grew up with television as completely corporate and very distanced. So the fact that we could break into this medium was intriguing to everyone, certainly."

Perhaps most importantly, TV Party also connected the post-punks and post-Warhol art crowd with the city’s emerging hip hop and graffiti scenes. Stein and Harry had already got to know Fab Five Freddy prior to TV Party, and the graffiti artist was a regular on the show, introducing its core participants to the emergent hip-hop culture.

Chris: "He took us up to this Police Athletic League event in the Bronx, and that was a real eye opener for everybody. That was probably about 1977."

Another regular contributor was Jean-Michel Basquiat, riding his own career train from the streets of Brooklyn to the galleries of uptown. Basquiat was active both in front of and behind the TV Party cameras, creating surreal scrolling messages in teletype that appeared on screen as the show went out live.

Chris: "Jean-Michel was involved all the way, he was on there frequently. His great moment was they had a blank wall which they had just put up in the studio and Jean did his graffiti on it. He wrote ‘Mock Penis Envy’ in his lettering and I think we had to pay to have it removed. And then he painted this big wall in the video for ‘The Hardest Part’, which was also whitewashed over. And he’s in the ‘Rapture’ video as well, but he’s the DJ. And there’s another moment of him wanting to graffiti a wall, and the director telling him he couldn’t, because he wanted it to be blank. He was always pushing it, but he was a good character. The other guys in the Hardest Part video, Freddy and Lee, were a little derisive of him because they had a much more flamboyant graffiti style. So it was like, you take that section of the wall and go over there."

Basquiat would reappear in the January 1981 video for Blondie’s ‘Rapture’, playing a DJ as a stand-in for Grandmaster Flash, who failed to show up to the shoot. Fab Five Freddy also makes a cameo appearance, as Debbie Harry delivers a mid-song rap that made his name familiar to mainstream music fans around the world. The lyrics to ‘Rapture’ also make oblique reference to TV Party with the line "Well now you see what you wanna be / Just have your party on TV". Harry’s and Stein’s interest in art, photography and other media meant that they were pioneers of the music video format and were relatively hands-on in their production, inviting their friends to participate and drawing on New York’s underground film-making tradition as much as commercial necessities.

Chris: "It was both. We just knew all of these guys. We’d see them around so it just seemed natural."

Debbie: "Yeah, and they were a bunch of hams anyway, they just wanted to get out there and be in a video. Everybody was pretty interactive, as I guess the word would be today. It was just part of our world at the time. I guess it was a much smaller world, at least in terms of the social world. It was just like, hey, come on, be in the video, and it was no big deal."

Looking back on early seventies New York, the era of glitter, punk, disco and drag, much emphasis is put on the decadence and craziness of those times. Yet looking at Chris Stein’s photographs of that era (recently collected in book form as Chris Stein/Negative: Me, Blondie And The Advent Of Punk), the main impression is of a very youthful innocence and fun.

Chris: "Oh yeah. The way it’s portrayed in films is never really right. I always see them show everybody wearing these bright colours and stretch pants and bright orange jackets, and it wasn’t anything like that. Everybody was very dowdy by comparison. It was more like that Spike Lee movie, Summer Of Sam. There weren’t a lot of people with giant green mohawks running around. That was maybe for a special occasion, but you just didn’t see it on a day to day basis."

Debbie: "I don’t think that Manic Panic and those kinds of hair products existed at that time. That came later. But they were inspired by that period. It’s kind of interesting."

Chris: "But the later portrayals are a lot more flamboyant than what it actually looked like."

Debbie: "Yeah, but look, when we first came over here, Sue Catwoman had blue hair."

Chris: "The King’s Road scene was a little more extreme than what was going on at CBGBs. It was certainly a lot more style conscious. In New York everybody just wore army jackets and the occasional motorcycle jacket. It was very low-key, in the beginning, anyway."

Debbie: "In the beginning, yeah."

Debbie, do they seem now like more innocent times, to you?

Debbie: "Totally, yeah."

Chris: "I remember Lester Bangs’ complaints about Debbie’s overt sexuality when in fact it was very innocent, certainly by comparison to today’s standards."

Debbie: "Yeah, it’s pathetic. I’m totally embarrassed."

Chris: "What, by Lester?"

Debbie: "No! By the fact that I wasn’t worse! I should’ve been worse. Much worse."

Blondie’s 11th album Pollinator is out on BMG on May 5. Pollinator is available to preorder now on CD, Cassette, Heavyweight vinyl and limited edition 7" box set via the Blondie website