We’ve got some particularly fine books for you this month – if nothing else, 2017 is shaping up to be a great year for comics, at least.

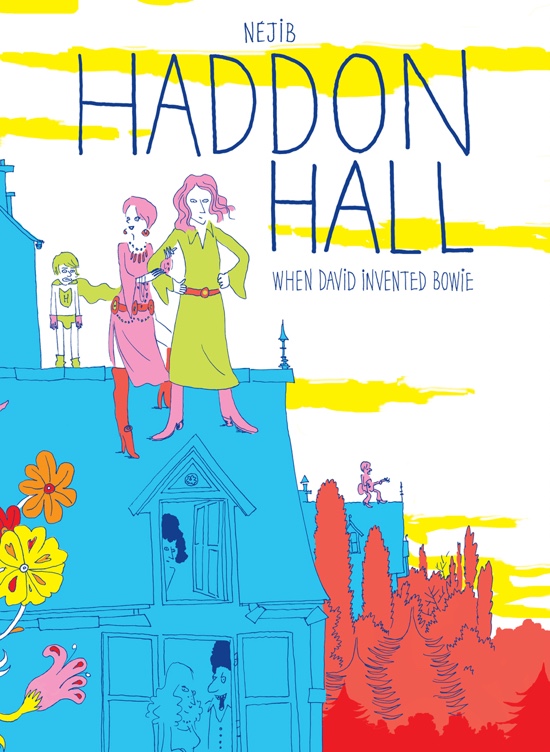

Néjib – Haddon Hall

(SelfMadeHero)

Haddon Hall, Néjib’s beautiful hardback from SelfMadeHero, is a graphical account of part of the period in Bowie’s life when he lived in a semi commune with wife Angie and many others, from 1969 to 1972. When we first meet him he’s a long hair in a dress, as on the original cover of The Man Who Sold The World, but by the end he’s shorn and Ziggy Stardust is emerging. Subtitled When David Invented Bowie, it covers one of his many transitional phases, but an especially significant one as he was so close to becoming a star.

As the book begins, Space Oddity has already been released. Throughout we see the recording of The Man Who Sold The World, arguably the heaviest solo album he ever recorded and one that sits somewhat strangely between Space Oddity and Hunky Dory. Although something of a divergence in his catalogue, it marked the arrival of Mick Ronson; while Bowie would return to gentler songs, he would also rarely be without a forceful lead guitarist for the rest of his life. Néjib depicts an interesting dynamic between Bowie, producer and bassist Tony Visconti, and Marc Bolan, painting a picture of an artist who somewhat detached from the recording of his own album. The book weaves together several strands – as well as the music, Bowie is shown struggling to define himself and to find a direction he believed in, and also dealing with a series of major life events. This is the Bowie whose father died, that wrote Kooks as his son was due to be born, and who had to admit failure in his attempt to help his beloved schizophrenic half-brother Terry.

Néjib takes a strikingly inventive approach throughout. The book is narrated by the house, and the bohemian lifestyle is shown through unbordered panels and frequently chaotic pages. Colour is used to show connections between characters, such as at a party early on when Bowie and Bolan are red while the guests are in blue. The cast is particularly (and predictably) good, with appearances from John Lennon and Syd Barrett, as well as future manager Tony DeFries. The depiction of creativity, such as the writing of Life on Mars (recently described by Woody Woodmansey on tQ in a particularly fine Baker’s Dozen) is charming. This excellent book is full of visual and narrative energy – the kind of book you stay up too late reading and have to force yourself to slow down to savour. I loved it. Pete Redrup

Michael DeForge – Sticks Angelica, Folk Hero

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Sticks Angelica, the new book from Michael DeForge, is a wide format hardcover with a particularly fine cover. Inside is a strange and very Canadian book. DeForge’s work is frequently strange, but is not always so rooted to a particular place as this. Sticks Angelica is introduced as “former: Olympian, poet, scholar, sculptor, minister, activist, governor general, entrepreneur, line cook, headmistress, mounty, columnist, libertarian, cellist”. That’s quite a CV by any standard, but also something of a red herring as we get nothing that can be considered an adequate explanation of how any one person can be so many things by the age of 49. All that’s in her past, though, and now she lives in Monterey National Park to avoid the public eye and a political scandal involving her father. It seems she’s swapped one form of attention for another though, as the animals in the forest are obsessed with her.

With few human characters, these animals play a major role in the book, particularly Oatmeal, a rabbit in love with Sticks. There are plenty of misdirected cross species crushes and liaisons, and power imbalances in relationships. One of DeForge’s talents is to create an off-kilter world that differs from ours in various strange ways, yet to do so convincingly, and in a way that sheds light on aspects of our own. As well as doomed romance, there’s an interesting justice system. Forest animals can be marked for death, and these are the only ones it is acceptable to kill, even for the other animals. Such status can be conferred for quite arbitrary reasons, but the laws must be obeyed. Sticks is pretty mean to some of the animals, but has a strong sense of justice as we soon discover.

DeForge’s comics often work on so many levels. Here he explores themes of justice through a character who is marked for death, and revenge through Oatmeal’s past. At the same time, the book repeatedly reaffirms its Canadian identity, and is also extremely funny in places (such as when the ants are representing Sticks and reply to her correspondence, or the brilliant Christmas sequence). As always, his artwork is utterly distinctive, rendered here in black and red, and full of details that reward close attention. Sticks Angelica is an absolute pleasure. Pete Redrup

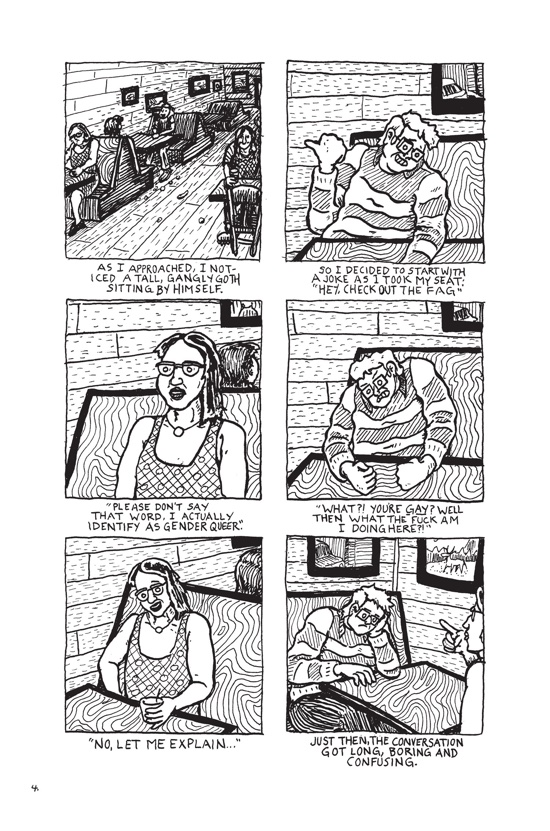

Tom Van Deusen – Scorched Earth

(Kilgore Press)

In interviews Tom Van Deusen comes across as eminently likeable. As a character in this book, however, he could hardly be more obnoxious. The fictional Van Deusen is overwhelmingly sexist, occasionally racist and entirely lacking in self awareness. It’s this latter quality that makes him entertaining, as virtually every encounter ultimately reveals his weakness and relative inferiority. At the same time, it’s perhaps a little too on the nose to read about sexist dullards who thinks the world of themselves; that appears to be what the news is for these days.

The bulk of the book is a long story about unsuccessful dating. Behind Tom’s swaggering but inept bro is an insecure man who calls his mum the morning after a casual drunken hookup to let her know he has a girlfriend now. Van Deusen has great comic timing, and the gently exaggerated character style deftly conveys the existential crisis that lurks beneath the surface. After the main story are several standalone strips, including one published in the excellent Rough House 3 anthology. Again, insecurity comes to the fore, and this often plays out over social media, with rows in the comments of his YouTube videos, and a Craigslist hire going badly wrong. In one story he tweets about being promoted, misunderstanding a conversation with his boss, and is ultimately set straight just as his gran sends balloons to his office in congratulation. These aren’t hard targets to hit, but it’s very nicely done, funny and appalling in equal measure, parodic yet plausible too.

It must be a lot of fun to write a version of yourself that gives in to every impulse, that reconstructs the universe with yourself at the centre, regressing to childhood. Scorched Earth gives the undeniable pleasure of watching somebody behave badly while knowing that they are the ultimate victim of their own actions, while being very funny at the same time. If only the news could feature a little more of that. Pete Redrup

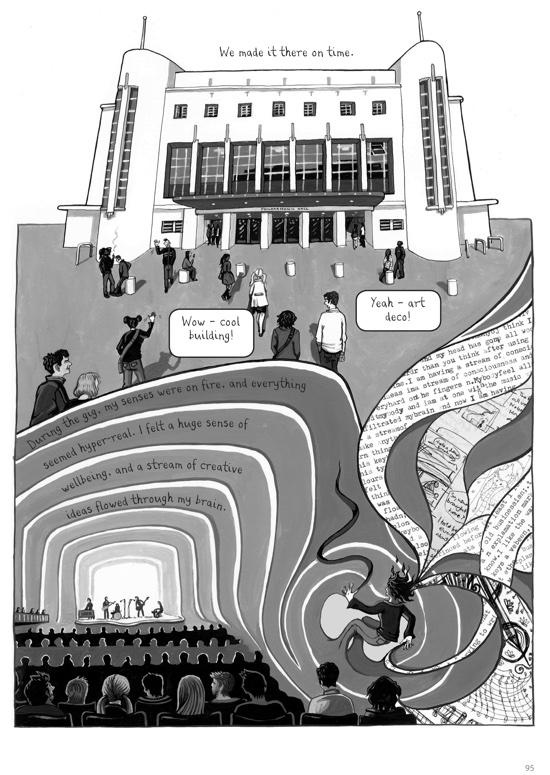

Paula Knight – The Facts of Life

(Myriad Editions)

In The Facts of Life, Paula Knight brings a playful and sophisticated design sensibility to the graphic medicine and autobiographical comics genre. The book follows her personal journey from birth to now, focusing on any reference to parenthood and specifically the expectations placed on women to become mothers. It is an honest and compellingly moving account of one woman’s navigation of an issue that is still not talked about enough. I’m not sure whether the conclusion of her question to procreate or not is meant to be a surprise for the reader; certainly the first scene of the book is ambiguous, showing Knight beaming back at the back seat of her car while a lorry in the foreground puns on the central question of the book as Mothercare is partially occluded to become ‘othercare’. I read the book without reading the quotes on the back cover (I like surprises) and I recommend you do too if you want the answer to that question to remain a surprise.

The cleverness of that framing and visual wordplay is typical of the wit and wisdom of Knight’s comic though, and throughout the book are dozens of gems of creative page design and use of unusual graphic elements to tell the story. In a particular favourite of mine an unrolling toilet roll becomes a ribbon, becomes a road and ties together taboo and a mindful awareness of the minutiae of everyday into an intensely poignant moment. Really you have to read it just to see how that is achieved. As an illustrator and graphic designer, there is no doubt at all that Knight is a master, but the pacing of the book as a whole doesn’t always live up to these golden moments and personally I felt that at least half of the childhood stuff was surplus to requirements. I understand the choice to ground the story of the adult author’s struggles (the real meat of the book) in an exploration of where her attitudes to motherhood came from, but really this could have been achieved with more impact in fewer pages, or perhaps spread out throughout the book in a more fractured timeline. This may be my personal issue with the tendency of autobiographical comics to give more information than is necessary, simply because the details are known intimately by the author. Less is more, people. In most The Facts of Life does this well, shows rather than tells, and is definitely worth a read, not least to engage with a hugely pertinent contemporary issue. Jenny Robins

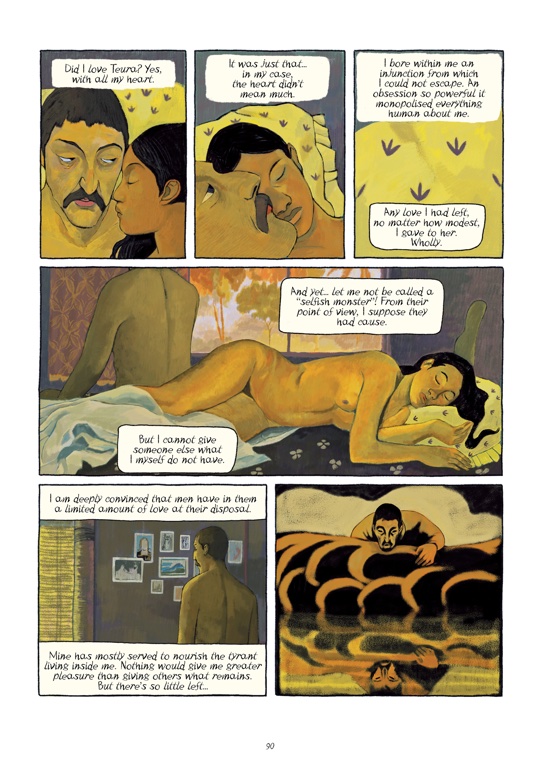

Fabrizio Dori – Gauguin: The Other World

(SelfMadeHero)

SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series translates the lives of famous artists into lavish graphic biographies, often illustrated in a style reminiscent of the artist’s most famous works, and is in my opinion one of the best things out there for booklovers not regularly accustomed to the comic book medium. Comics that most often break the confines of their traditional audience typically lean towards memoir and non-fiction, so if you’re curious about comics, but still haven’t picked many up, then there is no better place to start than with Gauguin: The Other World.

The fully painted and expressionistic book cleverly charts Gauguin’s life by beginning with a gloomy visit from a masked ghost, derived from Gauguin’s 1892 painting, Spirit of the Dead Watching. The ghost commands Gauguin to follow, and the two begin a journey through Gauguin’s memories. This framework creates an excellent excuse to fluidly pass through time, capturing Gauguin’s most formative experiences. On the slipstream of memory we quickly learn of Gauguin’s youth spent as a sailor, the early death of his parents, and the challenges of supporting his wife and family as a stockbroker while attempting to enter the European art-world as a self-taught painter. Time then jumps forward and we begin a more in depth look into Gauguin’s most important artistic period on the island of Tahiti that would eventually unlock his potential as an artist.

One of the most interesting aspects of the story is how unapologetically Gauguin acts.

On Tahiti, Gauguin discovers an Eden-like existence of unconstrained creativity and freedom, but is unable to silence his insecurity, ambition, and vanity. He believes his island life is pointless if he never earns the recognition he deserves, so he returns to Europe where his eccentric appearance and lifestyle earns him more fame than any of his work. In the end, Gauguin’s ghost allows him a choice to do things over, but Gauguin chooses death in favour of the legacy he knows his work will one day bring, ushering in the dawn of modern art, inspiring another artist in the Art Masters series, Pablo Picasso. Matthew Laiosa

Cathy Malkasian – Eartha

(Fantagraphics)

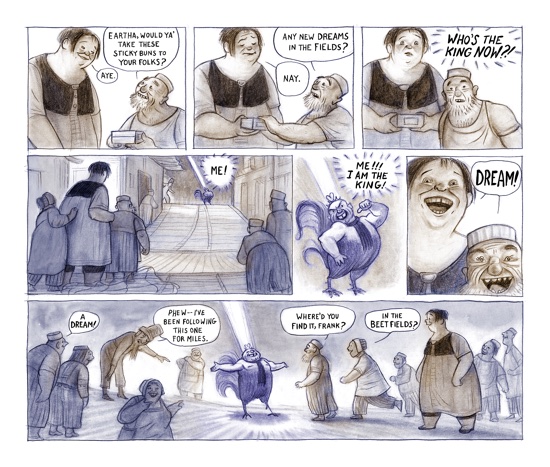

With only four books to date, Cathy Malkasian may not be the most prolific of creators, but she is certainly one of the most original. Percy Gloom, Wake Up, Percy Gloom, and Temperance all feature oddball realities that fall somewhere in between the minds of George Orwell and Dr. Seuss, and her newest, Eartha, is no exception. Perhaps the scariest thing about her latest work is how topical it is, considering that the book had to be created before Donald Trump was elected president. Science fiction used to take decades to prophesize societal shifts and technological breakthroughs such as the cell phone and iPad, but it seems that we now live in an age where if something can be imagined, then it will probably exist within the week.

Eartha tells the story of a gullible giant in a pastoral community of dwarves where dreams from a faraway city pop out of the ground to finish their narratives. Sadly, what once was a thriving valley filled with thousands of dreams a day is now visited by no more than a handful of dreams a week. Worried that something terrible has happened to the dreamers, Eartha journeys to the city and discovers a society where everyone is forced to stay awake in order to literally consume a non-stop supply of, I kid you not, fake news printed on biscuits evocative of President Trump’s twitter feed. Logically, the size of a biscuit limits the amount of information that can be distributed, so the ‘news’ is restricted to four word exclamations such as, “Hysterical jackass stabs recluse,” “Corn accident mauls has-been,” and “Fat jackass oozes calamity.” At one point in the story Eartha encounters the biscuit assembly line and amusingly asks a disgruntled janitor, “I see a lot of jackasses. Is the printer stuck?” And the janitor responds, “Of course not! The world is stuck!!” Which might be true since the people in control of this city is the Brotherhood of Bouncers, a clan of short balding males with the authority to grope any woman’s breasts of their choosing. Perhaps their slogan should be “Grab ‘em by the titties.”

Eartha is another frightening example of life imitating art, but the importance of storytelling is to remind us again and again that we can change. Unfortunately, change typically happens at a much slower rate outside of the world of fiction, but the more we expose ourselves and invest in quality storytellers like Malkasian, the faster real-world change can occur. Matthew Laiosa

Vincent Zabus & Thomas Campi – Macaroni!

(Europe Comics)

In the face of new technology I can be as stubborn as they come in my resistance to the latest gizmo or app, so I rarely read comics digitally. Unfortunately, some comics can only be read online, such as books from the all-digital publisher, Europe Comics. While reading comics in this format is not my preference, having access to a rapidly growing catalog of international creators is a dream come true. Perhaps as popularity increases, a greater number of foreign titles from all publishers will take physical shape, further diversifying the comic book medium.

One of the highlights from Europe Comic’s list of new releases is Macaroni!, the story of an elfish-looking boy named Romeo stranded with his ‘old pain-in-the-butt’ Italian grandfather, Nanno. Generational differences and awkward silences abound in a story where every movement and step of Romeo’s becomes a source of ridicule from his saggy-faced Nanno until, out of breath, the old man requires the use of an oxygen tank. Once relaxed, visions and memories appear before Nanno’s eyes in the form of ghost-like apparitions, and we quickly suspect that there’s more to Nanno’s curmudgeonly nature than meets the eye. Like Romeo we begin to show both patience and curiosity despite the barrage of insults muttered in Italian, gaining a deeper learning about both father and grandfather in the process.

Macaroni! is a story set in Belgium, but that does not limit its audience since the clash between young and old is a universal theme we can all understand. In one scene Romeo is horrified to find Nanno’s pet pig, amusingly named Mussolini, hanging upside-down after being gutted. Romeo refuses to eat dinner and accuses Nanno of learning to be a cold-blooded killer while fighting alongside the bad guys in WWII. Nanno exclaims that you can’t compare war with food, and it’s by eating a pig that never sees the light of day that you let the meat go to waste. The two storm off, and it is not until Romeo’s father explains Nanno’s famished upbringing that Romeo is able to calm down and eat his plate of sausages.

The book has an almost meditative quality with its quiet images of outdoor gardening, silent hallways, and phantom memories. Thomas Campi’s art jumps off the page with its vibrant countryside colours, and Vincent Zabus’ writing perfectly captures a child’s growing maturity. Recommended for fans of family dramas, WWII history, and slice-of-life stories. Matthew Laiosa