Appreciating Diamanda Galás’ voice is like learning to process the rhythm of a new language – it’s only after repeat listens that her words become distinct sound objects. The American singer originally trained in bel canto, a traditional operatic singing style loose in definition but with a Romantic emphasis on the natural accent and character of the singer’s voice. Her melodic lines often sound improvised, with distinct personalities developing with the unfolding of her voice, sometimes sounding as if she’s embodying a different character depending on her pitch and tone. There’s also a notably Gothic quality to her performances, too – and not just as a result of the supernatural range of her voice or her floor-length black gowns. Galás’ vocal carries within it a complex range of disharmonic emotional expressions, close to Edmund Burke’s characterisation of the Sublime: it is terrifying and voluminous, demanding shocked reverence from those who hear it.

Thematically, Galás takes an interest in the psychology of the individual thrown unwillingly into existential crisis. 1988’s The Masque of the Red Death was a direct representation of the lives of AIDS sufferers, and with In Concert At Saint Thomas the Apostle Harlem, Galás gives personality and a literal voice to the writings of Cesare Pavese and Ferdinand Freiligrath; two poets who, like her, are concerned with death and the political.

Indeed, the personal and political become entwined torture for Pavese’s protagonist in ‘The Prison’, who simultaneously holds a desire to perform solidarity with others while not being entirely committed to their political beliefs, resulting in a final betrayal. His more direct reference to death in ‘Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi’ becomes Galás’ concert opener. Similarly Freiligrath’s death-fixated ‘O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst’ becomes Galás’ ‘Die Stunde Kommt’ – a line taken from the poem itself.

The content of Pavese and Freiligrath’s poems are stretched and twisted by Galás’ strange elongation of vowels, sometimes to the point where the original words are difficult to distinguish. It is as if Galás has taken the poem as a loose script, feeling her way around the language, giving it a literal emotional tone which is somewhat lacking from mere spoken English. What Galás means by ‘death song’ is not obvious; perhaps it is to capture the impact of death on the living. It may well be a Gothic catharsis, an attempt to identify and present ceremoniously the psychological trauma of the death of another.

In the space of Saint Thomas the Apostle, Galás’ playing is complimented and enhanced by the church’s acoustics. Piano trills are crisp, loud and staccato, serving as a weird, scurrying rhythm to the tremulous vocals of ‘O Death’. Here Galás only occasionally pauses for breath, despite at times breaking into a phantasmagorical scream. The church’s natural reverb provides a chilling reverse-incubation to her trembling vibrato, and at times, her breath too itself is transformed into a fluttering instrument, frantically encompassing all angles of the space.

On All The Way, Galás’ piano and voice are mostly presented to us in natural form – at least in the sense that the timbre has not been changed through sonic manipulation. But live, there is the occasional use of what sounds like a panned echo effect, giving her vocals a more supernatural quality. It’s an enhancement, however, and without the strength of her “natural” voice to carry it, the effect would be significantly dampened. As a result, what is captured on In Concert At Saint Thomas The Apostle Harlem seems singular and unrepeatable. Her scream is embalmed in the audience’s reply of pure silence.

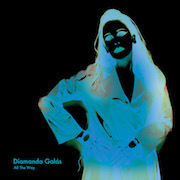

With its emphasis on piano, All The Way draws up the spiritual forms of both Thelonious Monk and Albert Ayler, through versions of both ‘Round Midnight’ and ‘Angels’. The Monk influence is clear – her piano is, on the whole, more subtly paced, contemplative and melancholic than on albums like La Serpenta Canta or The Singer. Her reworking of Jimmy Van Heusen’s ‘All The Way’ creates a similar alternative perspective on a familiar song to her reworking of ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’.

All The Way is particularly strong, however, for both the production of Galás’ piano and its melodies – there is an added, foreboding subtlety which comes through with more clarity here. What Galás does here will not be unfamiliar to those who have previously heard her other reworkings of what can be hesitantly called the pop music canon – ‘Let My People Go’ being the most prominent example. But what is there to change, other than for the sake of novelty? The distinctiveness of her voice is a theatrical, sure, but it is always eclipsed by extreme emotion.