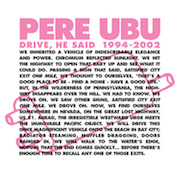

For the last few years, Fire Records have taken on the task of revisiting Pere Ubu’s impressive back catalogue in a way that avoids simply presenting handfuls of career highlights, outside of their original contexts, via the tired mode of the ‘Best Of’. Instead, the band’s various guises are grouped together according to their evolution. What we are given are the original albums: regrouped, remastered and repackaged. While Elitism For The People 1975-1978 focused on Pere Ubu’s abstract, youthful energy and Architecture Of Language 1979-1982 explored the period when the band entertained a spiralling anti-rock anxiety, Ubu’s third retrospective compilation, Drive, He Said 1994-2002, takes travel across the USA as its key concept.

The archetype of the American condition is the North American continent itself. Its vast and seemingly limitless expanse is pregnant with promise. Social, financial and spiritual rewards await those who strive hard to achieve their lot in life. If, for whatever reason, things don’t work out here, you can always pack up shop and try your luck in more arable lands. That’s the general idea behind all American conquests. It has inspired, and continues to inform, swathes of films, literature and music, not to mention questionable geopolitical motivations.

Drive, He Said collects together three studio albums, which all focus on this archetype to varying degrees: Raygun Suitcase, Pennsylvania and St Arkansas, as well as an additional disc of extras entitled Back Roads. All four records display an avid sympathy for the road. The clues are not only in the track titles (‘Memphis’, ‘Montana’, ‘Highwaterville’, ‘Drive’, ‘Slow Walking Daddy’ etc.), but in the lyrics and artwork too. For example, the covers of St Arkansas and Pennsylvania, – both of which were designed by John Thompson – feature road signs.

In ‘Folly Of Youth’, the song that opens 1995’s Raygun Suitcase, Ubu’s chairman, David Thomas, echoes Jack Kerouac’s transcontinental sessions on the infamous Greyhound bus: “I want to be your suitcase / I want to hang around inside your Greyhound terminal.” On The Road may have had its speed-addled moments – primarily in the form of Neal Cassady’s incessant chatter – but they can’t compare to Thomas’s desperate voice, which rides on a wave of caffeinated stamina. Parallel to this is the album’s production, which is wiry and restless. It recalls Hunter S. Thompson’s amphetamine-fuelled hunger for the American dream.

Cormac McCarthy’s desolate landscape from The Road is evoked on several occasions, most notably on ‘Memphis’, from Raygun Suitcase (“In the ghost town inside of my heart / all the downtown is parking lots”), and St Arkansas’s ‘Dark’ (“I drive because every ghost town rising in the dust / feels like a home to me”). Whereas McCarthy used the post-apocalyptic quietude as an excuse to dissect the intricate bonds of familial relations, Thomas, a solitary creature by nature, blames the ruins of the city for his desire to escape from it. Just like the boy protagonist in The Road, who eventually reaches the Pacific coast only to discover there is nowhere else to go, Thomas must concede that the ghost town is only a mirror of his state of mind and that it is the road itself that “yields to me / it sorta breathes and whispers out my name”.

When talking about Pennsylvania in his 2000 book, Double Trouble, Greil Marcus appropriately described its songs as “wistful, vaguely paranoid tales of displacement”. Throughout the compilation’s three-hour journey, it becomes abundantly clear that displacement is the band’s only concern. Lost highways are preferred to the collapsing suburban empires of Satisfied Cities. Indeed, this eight-year period (1994-2002) is the point in Pere Ubu’s career when David Thomas finally moved away from the largely unsuccessful ‘pop’ experiments of the late 1980s (although these do have their champions) and began to reverse back into the unsettling sonic territories that made the group so exciting in the first place. For a band who are characterised by their constant reinventions, a ‘return to your roots’ moment could have seriously backfired. However, the unifying concepts of travel and escape helped to refocus the group and aligned their work alongside texts of great literary merit.

Drive, He Said sees Pere Ubu riding an inherited vehicle Westward, out of Pennsylvania, down the back roads of Tennessee and through the desert to Nevada. They’re on a constant lookout for a good place to be. Many highway exits suggest a good life in a Satisfied City, but the band take no heed and hurtle on, beyond the charcoal smudge, where the ground meets the sky. Upon reaching the geographical full stop of the Pacific Ocean – beaten up and exhausted by endless promises of satisfaction – Pere Ubu abandon their car and catch a boat to Brighton. The great American archetype had an increasingly alcoholic Kerouac ping-ponging across the continent, threw Hunter S. Thompson knee deep into depression and even filled John Steinbeck’s George Milton with bitter disappointment. To hell with the wafer-thin mirage, Pere Ubu have work to do.