Annette Peacock appear on Late Junction’s International Women’s Day Special on March 8. You can listen back to the show here

New York composer and producer Annette Peacock is to make an appearance on BBC Radio 3’s Late Junction tonight, in order to mark International Women’s Day (March 8). During this rare appearance she will discuss her favourite pieces from female musicians with the show’s presenter Fiona Talkington.

Unlike these female musicians and composers, Peacock did not achieve significant popularity with the public during the crucial times around album launches – especially unrighteous considering the melodic accessibility of her second solo album, the 1972 RCA release I’m The One. Formed as much out of Charles Ives’ modernism as she is out of jazz and funk, Peacock disregards closed genre and instead neatly borrows and warps their motifs – ‘I’m The One’ melds with stylish ease the first MOOG synthesisers underneath minimal piano ballads.

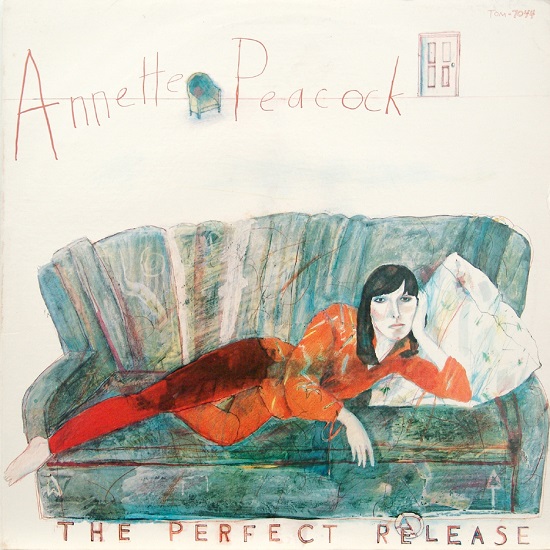

Again in 1979, she develops the lengthy spoken word jazz and funk influenced ‘Survival’, released as a closer to The Perfect Release. Peacock is not completely reliant on improvisation for songwriting, although she has a strong intuition (which remains now) for the development and unravelling of structures, both musical and political.

Peacock was also deft at discovering and bringing together ideal collaborators while undoubtedly always creating from within her own idiosyncratic ‘musical environment’. With these including Albert Ayler, Paul Bley, David Bowie, Brian Eno, Mick Ronson and Al Kooper, they have mostly been male, but this willingness to work with them never led her to sacrifice creative control. Prior to her overdue return to the UK and with (equally overdue) luck also its limelight, Peacock takes a moment to unravel the textured, humorous and uncompromising processes behind her musical output.

Meeting Mike Garson’s Brethren And Working On I’m The One

Annette Peacock: He played the keyboards on it. He was part of a band called Brethren and I was looking for a keyboard player. I heard him and liked the way he played so we discussed working together. I was trying to put together a band to make my first record and he said that he was working with this band the Brethren and that they’d be great for my music, so, we ended up recording together. They appeared on my first album I Belong To A World That’s Destroying Itself [aka Revenge]. After that I signed to RCA and they all played on I’m The One.

The First Experimentations With Synthesiser, Live And In Studio

AP: Not a lot of people notice the synthesiser parts on the ballad tracks. They’re very subtle little things going on deeper into the track. I enjoyed the process of actually creating the sound. I think that was what was so exciting about it. Because the piano is such an accessible instrument – you just touch it and it responds. It’s receptive and waiting for you to touch it. It’s an easy relationship – with the piano. But with a synthesizer, you have to actually create the sound. I don’t know what they are like today, but the ones I used were the original prototypes. They were very open in terms of the fact that they were basically oscillators. You had to create the sound with the attack, the rise, the sustain, the decay. It’s what’s known as the envelope, which gives you the possibility of something new every time and that’s what’s so exciting to me. The fact that you are actually there at the origin of the sound, inventing it. Actually making the utterance of the instrument. It’s a lot of hard work though. In those early days, in order to change the sound you had to use patches and cords that you plugged into things; it was very primitive. People in the audience at the gigs we did then were waiting 20 minutes between songs while I changed the sound of the synthesiser! They weren’t designed for a live performance – that was the problem. It was a studio instrument, built to record. We were taking this thing, which was the size of a big aeroplane cockpit, around all over to play it live. And then of course, at that time they were very unstable. You never knew what sound was going to come out of it – you didn’t really have control, because the current could be so different, depending on whatever environment you were working in.

Moving to England

When I left New York to play a week at Montmartre in Copenhagen, I had no idea that I wasn’t going to return. The plan was to stop in London and do a quick publishing deal then return with some money, but I missed the flight back hoping to close a deal and we hadn’t the money to buy another ticket. But my daughter and my gear were with me, and I had quickly became very fond of England. So naturally I decided to stay. The publisher provided free studio time and I began to use it. I’d brought a tape of a song ‘My Mother Never Taught Me How To Cook’ and I called Mick Ronson to overdub some guitar angst. A lot of musicians in London had heard that there were going to be sessions and just showed up. There ended up being 22 musicians in total on X-Dreams. Most of them had never played together, and all the tracks were first takes. It was very exciting.

Recording and touring The Perfect Release

I actually heard Jeff Beck’s forthcoming album Blow By Blow in the studio, and I just decided immediately that that was the band that I wanted to record with. And I wrote ‘The Perfect Release’ for them. I toured with The Perfect Release Band to promote the album. There was a performance scheduled in Paris, at the Bataclan. We travelled together on a hovercraft with the label head, the drummer, percussionist, bassist, the keyboardist and me. It was sold out, and the band got stoned and paranoid prior to the gig. They felt that they were being ripped off by the record company – they refused to go on unless they were paid more – I stood with them and a higher fee was agreed.

Visitation from Nico in Paris

Then afterwards, suddenly Nico was there. Nico, the Goddess from La Dolce Vita, who lit up the black and white screen so memorably with her effulgence. She had much changed, time had not been kind to her, but her essence still remained intact – mysterious and ethereal. She asked which drugs I took, and I said “I don’t.” She was astonished, dismayed and in her German accent said “You don’t take drugs?”. And she echoed the question. I invited her to come with us to dinner – we sat together and talked like sisters. She told me of her love for Alain Delon, how their child had been taken from her. Two events in her life from which she had seemed never to have recovered. And that was how the label head made his connection with Nico. I had heard the story of how he absconded with her tapes from Nico’s lawyer, when he called to notify me that an illegal recording was about to be released of my live show at the Bataclan. So I secured a barrister, went to court and was granted an injunction, as well as a release from the contract. Then I started my own label, ironicrecords.

The scrapped Obscure 11 record produced with Brian Eno

I was making a rare appearance in London, solo – I seldom perform. And Brian Eno showed up and began to set up his recording gear. He’d asked me to do an album that he would produce for his own label at the time, Obscure. The record would be ‘Obscure 11’. With him I met Rhett Davies at the studio, and Brian asked him “What have you got that’s new?”. And Rhett produced some options that Brian then tweaked, and I thought that this was such a perfect working relationship. I had fantasised about having that sort of connection with an engineer. But the album never happened because Brian and I had a concept disagreement. He wanted to feature my voice and disregard the music environment of the song, where the voice lived, and although he was probably right, that is not what I wanted.

Brian had decided to relocate to the US at this point, and asked if I would house his large Tannoy studio speakers. I was living in a spacious flat, part of a manor house that had been a hunting lodge belonging to Windsor Castle. The sound that those speakers produced was gorgeous and I came to rely on them for all of my acoustic decisions. Five years later I received a call that Brian wanted his speakers back! "What speakers?" I said. The thought of being separated from them was intolerable. But now I test everything on a boombox so, Brian, if you still want your speakers – let me know!

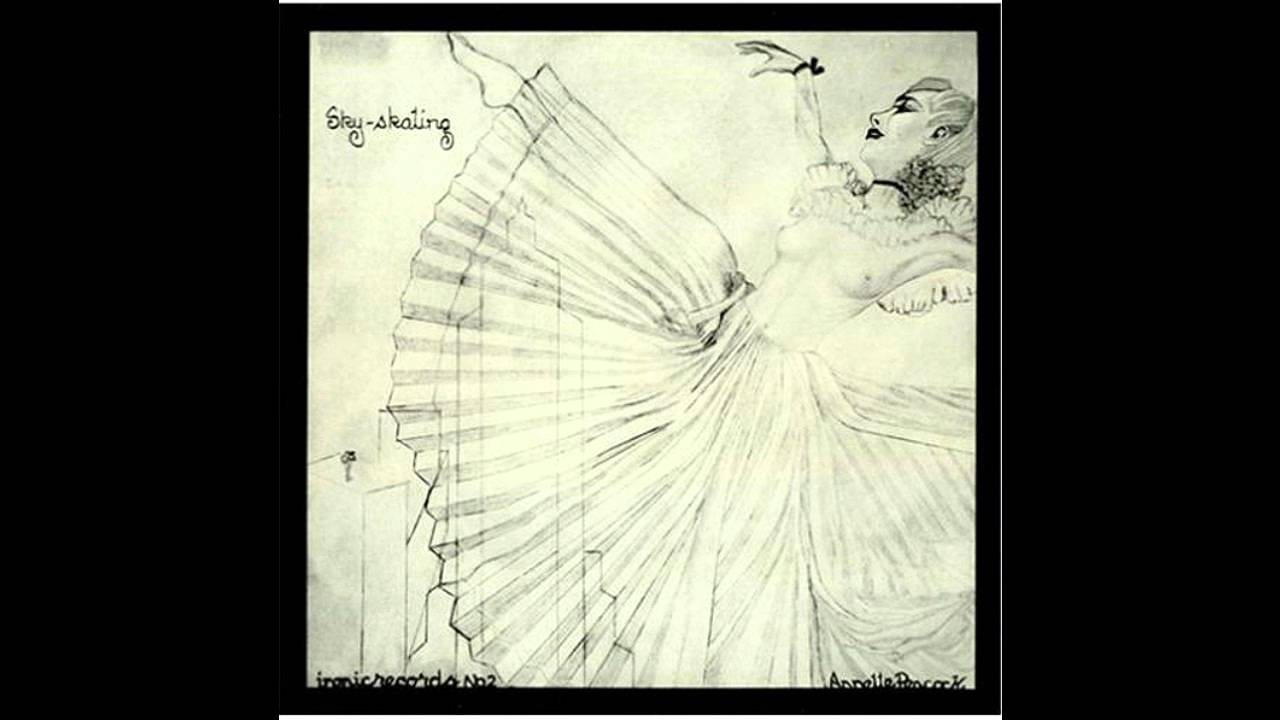

Establishing ironicrecords

Ultimately, the music I was going to record with Brian, I recorded and produced intact, live and as a complete entity. And it became Skyskating, the first release on my label. I launched ironicrecords in 1981 with the single ‘Skyskating’ which I had written as a birthday present for my daughter who has lead vocal on this track. I started ironicrecords for the freedom – I only release my own work through the label.

Creative freedom after I’m The One

I’m The One was an agreement that I had made with a major label to do a rock record. That was my conceptual rock record. But with the other records, I had a lot more freedom in terms of what I could do. The idea with X-Dreams was to approach the LP as a single, like each side was one piece. Side A very hard and aggressive and Side B very romantic and kind of sweet, really. Of course this was before CDs, when there was only vinyl – and the relationship between the two sides was important.

Recording at Island Studios

There was a British journalist, Richard Williams. He left music journalism to write about sports, but he’s back in it now. But at that time, he was writing for The Times and Melody Maker. It was so easy to promote your record then because all you had to do was get into the NME, Sounds, Melody Maker… It was a smaller marketplace. Anyway, Williams had been hired as the head of A&R at Island Records, and he offered the Island Studios to make a demo with the intention of signing me to the label. But shortly after making the recording, Richard was sacked during a change of managing directors. And the thought of losing those recordings was totally unacceptable. So although at the time I was homeless and crashing with a friend, I sent a large bouquet of flowers to the new director with a request for my tapes, which he kindly granted. Some of those pieces are among the second release, Been In The Streets Too Long, on my UK label.

The lyrical content on ‘Survival’ from The Perfect Release

The Perfect Release was made back in 1979 but it’s the artist’s job to see into the future. I don’t know where it comes from. You have these perceptions about things and you feel them very strongly. The ideas that you think about in your unconscious emerge into your consciousness but when you are in the creative process, there’s a very fine line between the two. You have to have a certain amount of consciousness to be able to manifest things, but it’s the unconscious which is liberated.

The dominating Western societies are represented by a white god. And Christ is portrayed as white, but was he? He was born in North Africa. The essence of Christ’s words is ‘unconditional love’. It’s a beautiful idea, though it seems unattainable via the dogma of religion. And this is the beginning of the delusion. Then there’s the hypocrisy, the concept of sin. But who determines sin? Those who are not capable of unconditional love, proven by their inability to accept differences, who translate and misinterpret the intentions of a god? Because if their message is accepted as truth, then the believer is permitting manipulation, and is all set-up to suffer and sacrifice – which is the other proposition: relinquishing the joy in life for the rewards in an afterlife – the place that exists on faith, as a deterrent. But why should one be prevailed upon, or expected to disassociate, from the self? How is that even possible? And how could that be the intention of any god, the creator? Love is acceptance and forgiveness and gratitude. Anything less is a deception and a “power ploy”.