The Moomins, like many children’s TV shows of a certain ilk (Bagpuss, Clangers et al.) have a lasting ‘vintage’ appeal, yet with Tove Jansson’s tender modern folk tales-turned-trippy as all hell animation, there’s a deeper level of adoration beyond mere nostalgia.

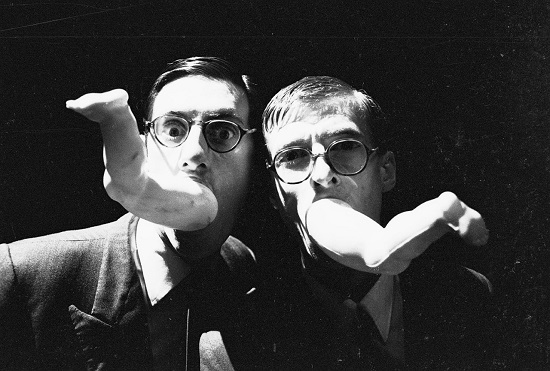

One of the abiding reasons the show holds such a fond place in so many hearts in the UK at least, is the work of two members of the Leeds’ potent post-punk and art scene in the early 1980s – the scene that gave birth to the likes of Gang Of Four, The Mekons and Impact Theatre Cooperative – Graeme Miller and Steve Shill.

Theatre performers and obscure Euro-soundtrack obsessives, inspired by Brian Eno and Young Marble Giants, Miller and Shill were approached by Anne Wood, who had licensed the original Moomins TV adaptation shown in Poland, and commissioned them to replace the original’s decidedly un-psychedelic dinner-jazz score. The result was an enduring, fiercely experimental approach that captures every essence of The Moomins’ irresistible, otherworldly brilliance.

Finders Keepers, in collaboration with Miller and Shill, have now released the duo’s score in full for the first time, a gleefully transporting listen splattered with exceptional textures that effortlessly blends reminiscence and progress, innocence and innovation. Below, Graeme Miller speaks to tQ about the story behind its inception.

The Moomins reissue is available physically now from Finders Keepers, and streaming above.

What can you tell me about your first contact with The Moomins stories? What drew you to them?

Graeme Miller: Well, actually I never come across them until asked to do the soundtrack to the UK/Film Polski version. I read the books and read and devoured the bittersweet oddball world they made. I read on into [Jansson’s] adult writing.

What was your immediate response to the idea of creating a soundtrack for The Moomins?

GM: I suppose our response was one of absolute enthusiasm. I think we understood that a childrens’ TV theme tune was a powerful cultural artifact.

Where did your initial interest in soundtracks come from?

GM: Driving the motorways of the UK Steve and I managed to piece together – without the aid of YouTube or any recordings the entire suite of incidental music for the French TV series The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. It was, like a lot of European and especially French TV and film music of the time very clever and coloured and exploiting an odd mix of electric, electronic and acoustic instruments, Ondioline synthesizer woven with harpsichord, electric guitar and string section. Odd textures in simple arrangement – we were already fans and somehow prior to being asked to score The Moomins had a real appreciation of not only childrens’ TV and film as a genre but how crucial the soundscape was to these.

Your background was at the more leftfield end of the music, art and theatre scenes of Leeds at the time, how did that influence you when composing the soundtrack?

GM: We were mercilessly absorbing and reworking all inputs. We were literally at the front end of sampling not only as a technology, but as an idea. The head of a donkey could be sewn onto the body of a cat and it did so best with visible stitching. Everything we did came out a bit wonky, but our unsophisticated fingers as musicians were matched by our sophisticated ears as artists.

Somehow our creations, influenced by Kraftwerk, Eno, Bryars and the entire ethnographic collection of Leeds City Library (an impressive selection) seemed to achieve a kind of autonomy, as if someone else had invented it or it had always been. This kind of re-purposing and juxtaposition that you hear in the Moomins putting ocarinas and Casios together really came out of the same left-field that has its roots in art movements from the 20s to the 50s in Europe and the US. You don’t really realize how that legacy is affecting you at the time.

Why do you think The Moomins, and by extension your music has had such an enduring appeal, beyond simply nostalgia?

GM:I think the Moomins soundtrack always was nostalgic in the same way Tove Jansson’s writing is a real dialogue between the adult and the child. There’s maudlin, self-involved, saccharine kind of nostalgia and there’s another form that is inherently melancholic and tries to mediate the parallel, yet never really meeting worlds of childhood and adulthood. All the best creative work for children embraces something of this. So while there may be a simple addictive chance to smell the TV food of your childhood again you have to see Tove Janssons own bittersweet relationship with childhood in a world that can be dark and challenging and just disorientatingly weird.

It’s possible to feel a sense of memory for things you never actually experienced and you get that often from the sheer tone. I know Steve and I were aware of this inherent nostalgic quality at the time – that it is possible to experience nostalgia for things that never happened directly to you. The other thing I hear now thirty-something years on, is simple inventiveness – two or three elements with strong quirky textures weaving together into a little sound-world. I think this makes the tracks stand up on their own. This probably from the sheer newness to us at the time of these affordable electronics, to their wobbly monophonic voices and you can hear something of that sense of discovery now in their re-discovery.