The best. Who is the best? Man like me is reviewing the best. Make some space, make room for the best. Limelight time, removing the rest. London keeps producing the best. Just sit back like you are the guest. Old MC’s keep proving the best. So who said that new is the best?

Apologies. That was me having a go at writing this review in the style of a Wiley lyric. The kind of relentlessly repetitive yet instantaneously innovative flow that has come to characterise the archetypal Grime MC, and a style that Wiley has more or less perfected over the course of a decade-plus long career.

There’s a reason why Wiley’s 11th studio album is entitled The Godfather. As one of the progenitors of this thing we now call Grime, Wiley has made us an offer we can’t refuse and risen to don status in the scene. Actually, he’s been present for as long as a Grime scene can be said to have existed. Early dalliances in post-UK Garage, post-2-step electronica gave birth to a restless subgenre that Wiley dubbed ‘Eskibeat’, complete with a host of ice-themed cult classics such as ‘Igloo’, ‘Ice Rink’ and ‘Ice Pole’. Eskimo Dance would become an ongoing legacy.

Like all good godfathers, Wiley has tasked himself with ensuring the spiritual and moral direction of his wards. In Grime, this isn’t so much a metaphor as an actual statement of fact. His paternalism is well documented, having been responsible for nurturing the talents of a whole clutch of MCs, up to and including one Dylan Mills, who, as we know, went on to achieve truly Dizzee heights of success. Not to mention Chip (munk) and Ice Kid (first seen spitting on Westwood’s BBC 1xtra show in 2007 while Wiley nods proudly in the background), both of whom feature on the song ‘On This’.

Benevolence runs straight through the central nervous system of The Godfather. The album is peppered with guest spots and features that read like a Grime fan’s dream cypher; little surprise when you consider the extent of Wiley’s affiliations in the scene. With nineteen features in total, the immediate risk is that Wiley, or any MC, might find himself eclipsed by the sheer brilliance of other assembled Grime stars, but this is where Wiley’s spark shines brightest. He draws out the best of his collaborators for the wider benefit of whichever song they happen to feature on, giving The Godfather a level of quality beyond the sum of its parts. I’ve seldom heard Scratchy as convincing as he sounds open ‘Bait Face’, while ‘Bang’ does for Ghetts what lit fuses do for fireworks, (ie: kaboom). Meanwhile, Devlin comes the closest to Renegading* Wiley on ‘Bring Them All / Holy Grime’, a song so incendiary that it doesn’t end so much implode on itself like a blazing star. Just a few examples of guest spots on an album that confirms Wiley’s uncanny ability to identify, organise and illuminate the talents of others.

How exactly Wiley manages to avoid playing the background is down to a simple fact: that he is a monstrously talented lyricist. If nothing else, The Godfather is a pupil-dilating showcase of lyrical skill, led by a Wiley who sounds as vital, urgent and hungry as ever. It took me three reloads to get through the first track alone, true story, every couplet searing into my working memory after the first listen. This is what Wiley is capable of and this is what fuels The Godfather throughout: raw energy and unflinching skill over brooding synths and 16-bit electronic phrasings. To this end, keen eared listeners will hear computer game samples woven into the fabric of ‘Birds n Bars’, the album’s appetite-whetting opener.

There’s an exhausting quality to Wiley’s output that will require Grime newcomers to take regular water breaks while listening. As accessible as the album is, complete with chantable hooks and a well-timed slow jam moment courtesy of ‘U Were Always Pt 2’, The Godfather is a relentless lyrical assault. With Wiley, it feels almost compulsive, as though he can’t help but spit bars, which is a fair summary of his career to date. Deep breath: 11 solo albums, 13 mixtapes (not including Roll Deep and Boy Better Know collaborations), a multitude of features, and 11 zip files of original material, deliberately leaked for free in 2010. There’s a trammelling consistency to Wiley that lends certainty to his artistry. When he tells us he ‘Can’t Go Wrong’, it’s as believable as a bricklayer troweling cement onto a wall. Incidentally, this is one of The Godfather’s standout moments, a song that pushes Grimy orchestral stabs into stellar territory while Wiley stomps through irresistibly quotable bars about MCing from the heart.

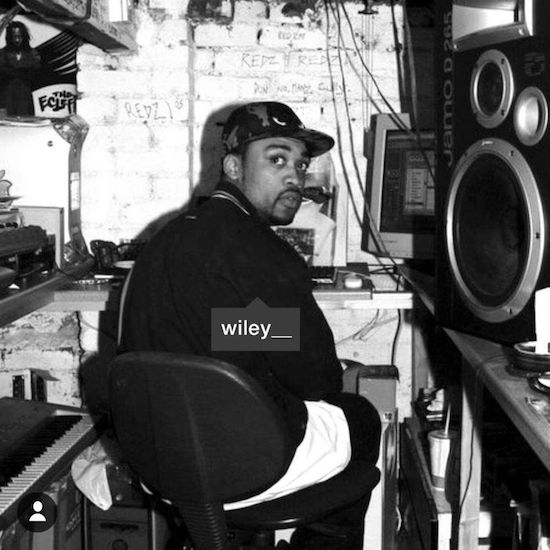

Wiley’s workmanlike approach to Grime is summarised neatly in ‘Laptop’, residing near the end of the album, a blippy ode to computer music production featuring Manga, the bespectacled Roll Deep member. It’s an honest slice of autobiography that highlights Wiley’s DIY approach to the music game. He knows his tools and he’s worked on his trade, making him a crafter and grafter as much as an artist. In fact, ‘graftist’ might be the best made-up word I can think of to describe Wiley’s position in the scene.

Wiley has gone on record saying that The Godfather will be his final album, but for all its reflections, it just doesn’t’ feel like a career-closer. At the same time, it doesn’t feel like a comeback attempt or eager bid for relevance in the context of Grime’s renaissance, either. In the most positive possible sense, it feels like just another Wiley album, which is no small praise considering how consistent Wiley has been since he first helped deliver Grime to our shared consciousness. As Grime grows beyond adolescence and takes increasingly confident steps into the mainstream, it’s clear that Wiley is a pivotal figure for the culture, a fact realised by an album that confirms the genre as a whole just as much as it does his own godfather status.

*’Renegade’ is a song by a rapper called Jay-Z, featured on an album called The Blueprint. It features a rapper called Eminem. On ‘Renegade’, Eminem delivers a performance so exceptional that it will forever eclipse Jay-Z’s contribution to his own song. For the purposes of this review, I am officially calling this sort of thing ‘Renegading’. This footnote, by the way, is so good that it may have Renegaded my review.

Jeffrey Boakye is the author of HOLD TIGHT: Black Masculinity, Millennials and the Meaning of Grime, due for release under Influx Press in July 2017