November 23, 1976: Ken Campbell’s Illuminatus!

When a young Scotsman named Bill Drummond arrived in Liverpool in the early seventies to complete his art school education, the city was overflowing with eccentric, creative characters, visionaries and dreamers. Perhaps the most influential of these was the beat poet and former merchant seaman Peter O’Halligan, who Drummond encountered in an old warehouse on Mathew Street- formerly home to the legendary Cavern Club, but by 1974 all but derelict. O’Halligan was very interested in dreams, especially one experienced in 1927 by the pioneering Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung. As recorded on page 223 of Jung’s book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung found himself in a "dark, sooty city" he identified as Liverpool (a place he never actually visited) and concluded that it was quite literally "the pool of life". Jung considered this the most significant dream he ever had.

O’Halligan thought it was quite important too. He decided that Jung’s dream specifically described the intersection of Mathew Street and Rainford Gardens- more or less the place where he and Drummond were then standing. O’Halligan had converted the old warehouse into an indie craft market and tearoom known as Aunt Twackies, following a prophetic dream of his own in which he’d seen a spring bubbling forth from the manhole cover in the middle of Mathew Street, and a burning building with a theatre in the basement, empty save for an old man and a copy of Playboy on the seat beside him. On hearing of Jung’s dream, O’Halligan further developed Aunt Twackies into the Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun, and decided to dedicate Aunt Twackies’ cramped parlour to the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool, the latest creation of maverick theatre director, writer and actor Ken Campbell.

Probably the single biggest influence on Drummond’s future career path, Campbell was a dozen years older than Bill and was already touring his anarchic Ken Campbell Roadshow round the pubs and working men’s clubs of northern England. This was fronted by the manic Sylvester McCoy, who in 1987 would narrowly beat Campbell to the role of the seventh Dr Who. But back in 1976 Ken Campbell had a different science fiction vehicle for his irrepressible vision: a nine-hour theatrical adaptation of the recently-published Illuminatus! trilogy. This philosophically mind-blowing sex, drugs and psychedelia parody-cum-extrapolation of every conspiracy theory and outlandish belief going in late 1960s America was written by two former Playboy letters page editors- Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson- who had found themselves at the sharp end of what would eventually stand revealed as Operation Mindfuck (OM).

Operation Mindfuck was the main activity of the loose-knit Discordian Society, and consisted largely of writing letters to magazines like Playboy, making the case for absurd and outlandish conspiracies, passionately arguing both for and against their existence, until the reader didn’t know what to believe anymore, and so was forced to embrace the contradictions, abandon belief and instead think for themselves. Robert Anton Wilson (RAW) soon became a Discordian himself, and memorably described this semi-satirical religion as "A Marx Brothers version of Zen" while expanding its remit considerably through his writings and insights. Established by Greg Hill and Kerry Thornley at the very end of the 1950s, Discordianism is based on the worship of Eris, Greek goddess of Discord, because if there’s one thing you can always rely on, it’s chaos. Eris’s symbol is a golden apple inscribed with the letter K, for Kallisti- "the most beautiful one". Discordians believe in the law of fives and are also very much impressed with the cosmic significance of the number 23, which seems to crop up far more often than it should.

Bill Drummond was 23 years old when he became the set designer on Campbell’s production of Illuminatus! He also started reading the book, but never finished it; years later, he would discover that the book had never finished with him. What made the most impact initially however was Ken Campbell himself, and Campbell’s dictum to "Make It Heroic!" Drummond painted this phrase in huge letters on the wall of his studio and proceeded to make it his maxim for life. But by the play’s opening night, 23 November 1976, Bill was already gone, having walked out to buy some glue and never returned.

The reason was that by this time, punk was brewing. Bill took the lessons that Campbell and, indirectly, RAW had taught him and applied them to the burgeoning Liverpool scene that met and dreamed at Aunt Twackies tearoom then played and posed at the legendary Eric’s Club just around the corner. Initially the guitarist in Big In Japan, with Holly Johnson, Ian Broudie, Budgie and Jayne Casey, Drummond soon set up his own indie record label, Zoo, alongside Big In Japan keyboard player Dave Balfe. Their signings included Echo & The Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes, and Drummond continued to manage both bands when they graduated to major labels.

Meanwhile in 1977 Illuminatus! transferred to the National Theatre, London, where the audience included a 20-year-old squat-punk and high school dropout called Jimmy Cauty. Born in Merseyside but raised in Devon, Cauty was an extremely talented self-taught artist who aged 17 had created a series of hugely popular hippy posters for Athena in the early seventies; one portraying characters from The Lord Of The Rings, and a series showing ancient sites like Glastonbury Tor and Stonehenge being visited by aliens in the mythical past. Illuminatus! had a significant impact on Cauty, but initially he too was content to put his ideas into practice as a guitarist and songwriter, forming Peel-favoured post-punk band Angels One-5 with his girlfriend Cressida Bowyer on vocals.

1981-86: Interstellar Ley Lines

Drummond’s eccentric – or heroic – management style soon earned him as much notoriety as the bands he was looking after. When in 1981 a journalist asked him why he thought so much talent had come out of Liverpool, Drummond told him about the interstellar ley line that touched down in Mathew Street, specifically hitting the manhole from Peter O’Halligan’s dream, from where it empowered the Cavern in the sixties, Eric’s in the seventies and so on. The only other places where it permanently connected with our planet were in Iceland and Papua New Guinea, Drummond claimed, but it could make temporary contact at any time or place, generating instances of spontaneous creative genius.

In his book 45, Drummond insists that he made all this up off the top of his head, but he quickly started to take it more seriously. He formulated a mad scheme whereby The Bunnymen would play a gig in Reykjavik at the same time as The Teardrop Explodes played in Papua New Guinea, and Drummond would stand on the manhole cover in Mathew Street and absorb the combined energies so generated, ascending, he believed, to "true genius". Unfortunately by this time The Teardrops had broken up, and in any case indie gigs in Papua New Guinea were hard to come by. Nevertheless in the summer of 1983 Drummond sent The Bunnymen on their infamous ‘ley lines tour’ that included a special performance in Reykjavik, and Drummond duly stood on the manhole cover at the appointed time to absorb the interstellar energy.

Prior to this, in 1982, the music press made much of the fact that Killing Joke singer Jaz Coleman had suddenly gone missing. He was eventually tracked down in Iceland, where he claimed he was looking for the interstellar ley line, and would be gone for some time. Killing Joke duly advertised for a new singer and Drummond, who had never even heard Killing Joke, felt compelled by this bizarre Jungian synchronicity to phone up for an audition. He didn’t get one; Coleman returned, but bassist Youth quit, having had enough of his singer’s occultist, paranoid behaviour. Youth decided to form a new band, Brilliant, and after several line-up changes they settled down to a trio of Youth, singer June Montana, and Jimmy Cauty on guitar. In 1984 they were signed to WEA Records by the company’s newest A&R man: former Echo & The Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes manager Bill Drummond. This was Bill and Jimmy’s first meeting, and like ley lines they connected immediately.

Drummond was impressed by how a cocky new production team known as Stock Aitken Waterman had managed to create a perfect slice of hi-energy dance-pop with his fellow veterans of the Liverpool punk scene, Pete Burns and Dead Or Alive. ‘You Spin Me Round’ was a huge worldwide hit, so Drummond paired them with Brilliant in hopes of similar success. This wasn’t to be, though the video for Brilliant’s SAW-produced single ‘Love Is War’ is notable for showing a glammed-up Cauty emerging from a wrecked and pink-painted 1968 Ford Galaxie American police car, with more than a passing resemblance to his future collaborator Ford Timelord.

By 1986 Jimmy Cauty had left Brilliant to form Zodiac Mindwarp & The Love Reaction with former Flexipop art editor Mark Manning, while Drummond had quit his A&R job to write his memoirs. His parting shot to the music business was a premature midlife crisis of an album entitled The Man, released on Creation Records and featuring Drummond’s distinctive gruff, Scots vocals backed largely by Australian indie darlings The Triffids. The album was accompanied by a grandiose press statement in which Drummond declared that he was 33 and a third years old and it was time for a revolution in his life. The running time of the album, which of course plays at 33 1/3, is also approximately 33 and one-third minutes.

That should have been it; like his first musical hero, Elvis Presley, Bill Drummond had left the building. He decided to use some of his free time to re-read Illuminatus!, thinking that maybe this time he’d finish it. But he was still on book one come 1 January 1987, when he phoned up Jimmy Cauty (who had already left the fledgling Love Reaction and formed The Orb with ex-Killing Joke roadie Alex Paterson), with an offer he couldn’t refuse: to start a hip hop band called The Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu, that would finish off the job punk started and take down the whole illuminati-controlled music industry once and for all.

1987: What The Fuck Is Going On?

In Illuminatus! the Justified Ancients Of Mummu are an ancient Babylonian sect who worship chaos, and are engaged in a centuries-old war with the shadowy, control-fixated Illuminati. The leader of the JAMs is legendary bank robber John Dillinger, known for using the JAMs motto "Everybody lie down on the floor and keep calm" whenever he undertook a heist. Thought dead, Dillinger in fact becomes a major music industry executive, although the majority of the rock business is of course controlled by the Illuminati, who taunt Dillinger by inciting the MC5 to call their most well-known recording ‘Kick Out The Jams’. The Illuminati’s ultimate plan is to "imminentize the Eschaton", or bring about the end of the world, by utilising the energies generated at a huge rock festival in Bavaria known as Woodstock Europa. The JAMs meanwhile establish a complex network of alliances with Discordian groups such as the Legion Of Dynamic Discord (LDD) and the Erisian Liberation Front (ELF). Some of these have been known to burn any paper money they get their hands on: "Instant demurrage, they call it." The LDD is led by mad pirate genius Hagbard Celine from his yellow submarine, the Leif Erikson, usually accompanied by a talking dolphin named Howard. Ideas and images from the book would recur throughout Bill and Jimmy’s work from this point on.

Drummond saw in Illuminatus! a metaphor for his modernist critique of a backwards-looking music industry in thrall to spurious notions of authenticity and middlebrow taste. Drummond never had much time for musicians or bands. He loved records, and Pop Music in its most abstract, idealised form, but was also happy to embrace the contradictions inherent in its hybrid of commerce and art. The fact that the most exciting popular music being made in the late eighties was American hip hop seemed to prove him right. Here was punk as it should have happened: music that could be made by anyone with a microphone and something to say, and access to the democratising technology of drum machines and samplers, swiftly becoming just as affordable as the once iconic but now surely outmoded electric guitar.

The experience of working with Stock Aitken Waterman was just as important for Drummond as working with Ken Campbell a decade earlier. As Drummond and Cauty saw it, SAW’s approach was as revolutionary and artistically valid as Andy Warhol’s Factory. SAW productions were true pop art, records made quickly with minimum fuss and minimal input from actual musicians: just a singer, a beat and the whole of recorded musical history to stealthily sample from. SAW + RAW = The JAMs. It was an equation of True Genius.

The JAMs were always intended to last for just one year. Like bank robber John Dillinger, they would get in, do the job and get out. Their records were banged out as fast as possible, crude, bolt and shunt creations that used lengthy, recognisable samples as much for what they signified as what they sounded like. They were also explicitly political; their first single, ‘All You Need Is Love’, stole from The Beatles and Samantha Fox and dealt with media hypocrisy regarding the AIDs crisis. Their debut album, 1987: What The Fuck Is Going On? included songs like ‘Don’t Take Five (Take What You Want)’ that encouraged wholesale pilfering of copyrighted material, an anarchist exhortation to liberate The Music from The Business and return it to The Kids. ‘Downtown’ was an angry Christmas single that railed against organised religion in an age of consumerism, poverty and homelessness, but nevertheless singularly failed to come down on the side of rational atheism or Marxist ‘opium for the people’ platitudes.

At the same time, The JAMs also pushed their mythology for all it was worth. Initially they tried to conceal their true identities: Drummond claimed to be King Boy D, a Glaswegian docker turned rapper, while Cauty was his surly accomplice, Rockman Rock. Their lyrics continued to draw from Illuminatus!‘ seemingly bottomless well of ideas, images and archetypes, but the still essentially post punk music press was happier discussing them in terms of Situationism rather than Discordianism, which seemed like an obscure hippy holdover. Meanwhile the JAMs continued to promote their records with graffiti campaigns and defaced billboards, and came up with one of the greatest band logos ever, a pyramid overlaid with a ghetto blaster that perfectly represented their mission. Cosmic Triggers With Attitude, The JAMs were Licensed To Illuminate.

Operating entirely independently out of Jimmy and Cressida’s Stockwell squat, known as Hector’s House, The JAMs recorded their debut album in six days in the squat’s cramped basement studio, which Jimmy had named Trancentral. They soon ran into difficulties when Abba’s lawyers demanded the album be withdrawn and destroyed due to the track ‘The Queen And I’ that sampled pretty much the entirety of Abba’s wedding disco staple ‘Dancing Queen’. The JAMs were forced to capitulate, but nevertheless drove their Ford Galaxie police car (now known as the JAMsmobile, and customised with the pyramid blaster logo on the doors and the number 23 on the roof) to Abba’s Stockholm PO Box address, claiming that they intended to meet with their management to discuss the situation. Like most of their actions, the pilgrimage to Stockholm was symbolic: Bill and Jimmy intended to give the remaining few LPs a Viking funeral, piling them on a raft and setting it alight before sailing it majestically out across the fjords. Like most of their actions, this didn’t go entirely to plan: a handful of the albums were burnt in a field, while the majority were thrown over the side of the cross-channel ferry.

1988: The Tardis and Top Of The Pops

Following a somewhat more sophisticated second JAMs LP, Bill and Jimmy set out to make a house track based on the Dr Who theme, but soon found that the only way it would work was if they used ‘the Glitter beat’ – the debased ur-rhythm of 1970s British pop, as utilised by the not-yet-disgraced Gary Glitter and his contemporaries, The Sweet. The result sounded great, but it also sounded unmistakable like a novelty record. And if they were going to make a novelty record, they reasoned, then they had to make it as cheesy, corny and tasteless as possible, and make sure it got all the way to the top.

The late eighties were arguably the heyday- or nadir- of the novelty single. In 1988, British pop fans were still mentally scarred by such recent number ones as ‘Star Trekkin” by The Firm, ‘The Chicken Song’ by the cast of Spitting Image, and Cliff Richard and the Young Ones’ remake of ‘Living Doll’. But for all it revels in the form, ‘Doctorin’ The Tardis’ remains a substantial cut above such trashy fare. Its fusion of glam rock, terrace chants and Dr Who is still an irresistibly giddy rush, and the single duly got to number one. This meant an appearance on Top Of The Pops, but the show’s producers refused to go along with the conceit that the record was made by a car, Ford Timelord (Jimmy’s 1968 Ford Galaxie in yet another regeneration), meaning that Bill and Jimmy got to make their first of many memorable appearances on the show. Now renamed Time Boy and Lord Rock, they mimed alongside two drummers and a couple of rubbish home-made Daleks, brandishing flying V guitars and dressed in top hats and capes. More chilling, with hindsight, is their 1988 Christmas Top Of The Pops spot where Bill, Jimmy and three drummers are all dressed as the Spanish Inquisition – or the Illuminati Prime – in black robes and pointed, full-face hoods as Gary Glitter himself joins them from amid clouds of dry ice, like some unrepentant sinner being escorted to the gates of Hell.

They followed the hit with a book, The Manual (How To Have A Number One The Easy Way), which referenced original Discordian Kerry Thornley’s Zenarchy newsletter (and later book), and was dedicated to "the memory of Don Lucknow". Lucknow was the alias used by young British games designer James Wallis, who had come to Discordianism via RPG fandom, in writing a letter to Bill and Jimmy warning them that they would be in "deep shit" if they continued to use the name of The Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu, because the real JAMs and/or the real Illuminati would be sure to take steps to deal with them. They were, he assured them, in over their heads and playing with forces they didn’t understand.

Ever ready to respond to random bolts of weirdness, The JAMs immediately began work on a single and graphic novel, both called ‘Deep Shit’, though neither was ever completed. Wallis / Lucknow is still very much alive, but The Manual is still the best book about how pop music worked in the late twentieth century, an era when you could still dream your way to some strange kind of success while signing on the dole and doing business in phone boxes. In Discordian terms, The Manual is a guide to manipulating your reality tunnel and bringing the universe into line with your wildest fantasies by using belief, imagination, causality and a pinch of mysticism. It’s chaos magic.

1989-91: Entering The White Room

Meanwhile, the weird letters kept coming. In mid-1988 The JAMs received a legal contract from "Eternity" which required them to make an artistic representation of their journey to somewhere called "The White Room" in return for access to the "real" White Room. Against all official advice, Bill and Jimmy signed the contract and decided to spend the proceeds from their number one hit on making a film of that name that would fulfil their contract with Eternity while also being the first "ambient road movie".

The film – which deserves a whole article to itself – was never finished, and the soundtrack album was scrapped after its lead single, the existential Pet Shop Boys pastiche ‘Kylie Said To Jason’ failed to chart. Next up was the ‘Pure Trance’ series: five 12" singles of minimal techno aimed directly at dance nights like Paul Oakenfold’s Land Of Oz, at Heaven, where Cauty and Alex Paterson were the back room DJs. Here and at the inevitable Hector’s House after-parties the pair mixed up old Pink Floyd and Steve Hillage LPs with heavy dub, Steve Reich and Brian Eno. When they started pursuing this more ambient musical direction as The Orb, Cauty wanted to release the results on KLF Communications, but in 1990 Paterson accepted an offer from Big life Records instead. The pair split, with Paterson keeping the Orb name while Cauty released the tracks they’d been working on at Trancentral as the album Space, with Paterson’s contributions removed. This period also spawned the KLF album Chill Out, which brought Bill Drummond’s love of plangent lap steel guitar and Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac into the ambient house mix.

As for the Pure Trance series, there were to be no gimmicks, no stunts and no promos to the press: these would be serious underground dance records, free from any damaging associations with The JAMs or The Timelords. Only the first two were ever released: ‘What Time Is Love?’ and its answer record, ‘3AM Eternal’. The Pure Trance project was abandoned when Bill and Jimmy decided to re-record these tracks as unashamedly commercial but credible pop-dance singles. Along with ‘Last Train To Trancentral’ (also originally recorded for the Pure Trance series) these made up The KLF’s ‘Stadium House’ trilogy that in 1991 saw them crowned the biggest-selling singles band on the planet.

Now nothing was beyond their reach. If they wanted to record a version of ‘Justified And Ancient’ (the lyric and melody originally part of ‘Hey Hey We’re Not The Monkees’, the opening track on 1987: What The Fuck Is Going On) with country legend Tammy Wynette, then the music industry was happy to oblige. If they wanted to rerecord ‘What Time Is Love’ yet again with rock guitars, choirs, Jim Steinman-level overdubs and Deep Purple’s Glenn Hughes on vocals in a ridiculously over the top attempt to "break America", then sure, and why not film a video with the band and entourage battling the elements aboard a Viking longboat on a Pinewood stage set to boot?

The JAMs name was briefly resurrected for the dour provincial namecheck-techno of ‘It’s Grim Up North’, while The White Room became the title of The KLF’s best-selling LP. Through it all, the band dealt with the media on their own terms; via their increasingly epic videos, their ever more outlandish Top Of The Pops appearances, and full-page communiques as paid adverts in the weekly music papers. They made maybe half a dozen live appearances, usually at semi-legal outdoor raves, with an ice cream van replacing the JAMsmobile as their trademark vehicle. At the Helter Skelter rave in Chipping Norton they threw £1000 in Scottish pound notes out to the audience, an act – like creating crop circles of their logo, or flying representatives of the world’s press out to the remote Scottish island of Jura for ‘The Rites Of Mu’ (a robed procession up a bleak Hebridean hillside to witness the burning of a wicker man) – that many dismissed as scams or pranks. But this was missing the point: The KLF were building a complex mythology from their own personal obsessions, mining the Jungian unconsciousness from which cows, sheep, ice cream vans and horned, robed figures emerged as strange new archetypes. To a large extent they also felt they had no choice in their actions. Time and again, Bill and Jimmy would insist that they didn’t know why they did what they did, but that being in The KLF carried certain responsibilities, even if it took them to some extremely dark places. They would also distance themselves from their creation, asking, "What would The KLF do?" And eventually the answer came back that, rather than become just another whacky, industry-friendly pop act or, worse, tame corporate rebels, The KLF would self-destruct and end it all.

1992: Exiting The Black Room

It was clear that moment had come when, at the 1992 Brit Awards, The KLF were told that they would be sharing the Best British Group award with Simply Red. It was time to take a stand: to do something so shocking, so final that it could never be construed as a prank, but would make them genuine pariahs and outcasts.

As always, it didn’t quite work out as planned. At one point, Bill was going to cut his own hand off on stage; at another, he and Jimmy were all set to drench the assembled music biz dignitaries in buckets of genuine blood, fresh from the slaughterhouse. In the event, they dumped a dead sheep in the lobby of the Royal Lancaster Gate Hotel, location of the Brits after-party, with the note, "I died for ewe" pinned to its carcass. And on the night they performed a version of ‘3AM Eternal’ with East Anglian grindcore band Extreme Noise Terror while Bill stumbled around on crutches in a filthy leather greatcoat and kilt, shouting garbled abuse into the microphone, and Jimmy readied himself for his climactic solo that never came, as the lead popped out of his guitar at the crucial moment.

Instead the climax happened when Bill machine gunned the audience from the stage. He was firing blanks of course, but with the hindsight of these more terror-conscious times, it’s hard to imagine exactly how they got away with it; or rather, how they were allowed to bring an actual machinegun on stage with them at a major music industry event at all. But in 1992 this was semi-acceptable behaviour. Some among the industry and media were shocked and scandalised, but more made a point of saying just how much they loved it. It was another great stunt from those crazy KLF guys; whatever would they think of next?

What The KLF thought of next was leaving the music business entirely, which was surely always the intention of their Brits outrage. They had obeyed the Law of Fives, operating as a band for roughly five years and achieving five top five hit singles. Although they’d begun sessions for a new album, The Black Room, in collaboration with Extreme Noise Terror, these were abandoned as the dark and heavy nature of the music being created reflected Bill and Jimmy’s increasingly fragile mental state. It seems that the pair were both on the verge of breakdown, and a few months on from the Brits, they announced they were quitting. Not only that, they were deleting their entire back catalogue, which as Select magazine prophetically stated at the time, was "equivalent to piling up maybe a million or more five pound notes, dousing them in petrol and… wooooof."

1993 and after: K Cera Cera

Two years later, on 23 August 1994, Bill and Jimmy returned to Jura and burnt a million pounds. This was the remaining profits from their career as The KLF, which they had pledged to put to use via The K Foundation, their "imaginary art foundation" for "the advancement of kreation". The K Foundation’s initial announcements suggested that they were interested in breaking free of the very concept of "rational time" and replacing it with "K Time". They also recorded a version of the old standard ‘Que Cera Cera’ with the Red Army Choir, renaming it ‘K Cera Cera’ and insisting it would only be commercially released once world peace was achieved. But they came to wider attention when The K Foundation targeted the 1993 Turner Prize, announcing a shortlist for their own award for the worst piece of art produced that year- one that was identical to the Turner Prize shortlist. Their prize would be £40,000, compared to the £20,000 offered by the Turner; in the end, Rachel Whiteread was the lucky recipient of both.

Prior to this, The K Foundation had used their million pounds to create their own work of art: they nailed the whole lot, in fifty pound notes, to a pinewood frame and presented it as a work entitled Nailed To The Wall. They announced a reserve price of £500,000, pointing out that while inflation would steadily erode the cash value of the million pounds, the piece’s value as art would surely rise. Any buyer would have to decide whether to take the artwork apart and pocket the money- immediately doubling their investment- or keep it as a work of art, presumably until its face value became greater than the sum of its parts.

No-one took the bait. The media refused to take it seriously, and galleries refused to exhibit it. What could they do? They had committed themselves to only using the money as art. It couldn’t be spent, or given away, but they had to something with it. One day, Jimmy casually suggested burning it. Both were horrified at the idea, but it was too late. The concept was out there. It was awful, in the true sense of the word, but they knew it had to be done, even if they didn’t exactly know why.

No-one burns a million pounds of their own money as a prank or publicity stunt. The reason they did it in the middle of the night on a remote Scottish island, rather than in a public performance, was actually to try to reduce the shock value. In one sense this was Bill and Jimmy’s ‘4 Real’ moment, proof that they were serious and committed, but in another sense it was just something they had to do. On 5 November 1995 they signed a contract agreeing to end The K Foundation for 23 years, after which time they would be able to provide an appropriate response to their burning of £1,000,000. This contract was written on a Nissan Bluebird that was pushed off Cape Wrath, on the north-western tip of the Scottish Highlands, falling 120 feet onto the rocks below. Although this means that they cannot talk about the money burning until the contract expires in 2018, they have both very clearly been haunted by it ever since. Yes, they have regrets. But they also feel like they truly had no choice.

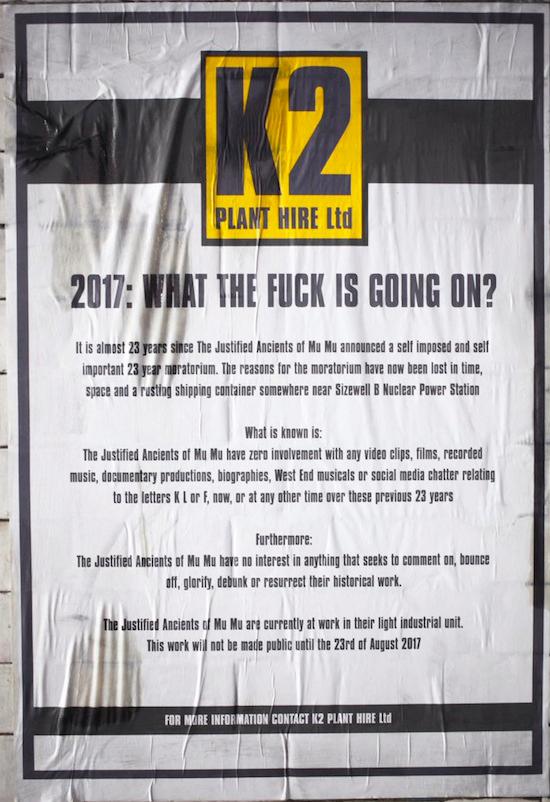

Alongside The K Foundation, Bill and Jimmy also set up K2 Plant Hire, with the intention of taking a couple of bulldozers down to Stonehenge and "fixing up" the ancient monument. They also pledged to build a People’s Pyramid as an alternative to the Millennium Dome, including a brick for every person born in the UK in the twentieth century. This tied in to their 1997 "comeback" as 2K, with yet another reworking of ‘What Time Is Love’, retitled ‘Fuck The Millennium: We Want It Now’. This was a collaborative effort with artist Jeremy Deller and his ‘Acid Brass’ project: the single featured the Williams Fairey brass band and the National Retired Life Boat Men’s Choral Society. A 23-minute performance at the Barbican, directed by Ken Campbell and also featuring Zodiac Mindwarp as the evangelical Reverend Bitumen Hoarfrost, preaching hellfire and damnation while the artificially-aged JAMs careered around in wheelchairs, dressed in pyjamas and with their trademark horns attached to their foreheads, will live long in the memories of all who were there.

At the beginning of this year a blurry, timestretched 45-minute collage movie appeared on YouTube that mashed up the band’s old videos and TOTP appearances with bits of Withnail & I, The Day Today and Dr Who, clips of Alan Moore and flashing messages that underlined just how unique, magical and inexplicably weird The KLF really were. The film was originally made for Bristol’s Cube Cinema in 2015, where it was screened at an event that involved the ritual burning of £1000 and an appearance by John Higgs, author of the book The KLF: Chaos, Magic And The Band Who Burned A Million Pounds (2013). This slim, unprepossessing volume has quietly become one of the most important texts of the last few years, retelling the story of The KLF in a socio-magical context that foregrounds the influence of Discordianism on their work and also connects them to Dadaism, Situationism, the work of Alan Moore and the living history of Dr Who, among other elements.

Not only does the book lay down a new musical creation myth for the 2lst Century- replacing all those hoary old tales of the summer of love and the scorched earth of punk with a more modern concoction of techno, raves and sampling- but it also provides a handy primer for the current Discordian revival, a new spin on the old ideas that drive so much of Drummond and Cauty’s work. Over the past five years Discordianism has been at the heart of a growing counter-cultural movement, one that includes the life-changing theatrical adaptation of Robert Anton Wilson’s Cosmic Trigger by Ken Campbell’s daughter Daisy, returning to the London stage this May, and last summer’s Festival 23, which featured a second screening of the Cube Cinema film, Jimmy Cauty’s ADP installation, money burning ceremonies, talks by Higgs and Campbell and much, much more.

A couple of days after the film appeared, K2 Plant Hire made a statement in the form of a poster that was conveniently "spotted" by their long-term associate Cally Callomon. This made clear that The KLF would not be returning, but that The Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu were currently at work on a new project that would be made public on 23 August 2017. This date marks the 23rd anniversary of the Jura burning; the ashes of the money were made into a brick, the purpose of which, Bill said at the time, would be revealed in 23 years. In the sleevenotes to a 2015 documentary on Bill Drummond, Imagine Waking Up Tomorrow And All Music Has Disappeared, it states that "Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty’s sculpture The Twenty-Three Year Moratorium will be completed by 23 August 2017". What form this sculpture will take, and whether it will involve the million-pound brick, has yet to be confirmed.