"The lack of any serviceable or even credible ruling ideas has created a situation that resembles a tabula rasa – almost anything might appear. The phenomenon of the UFOs may well be just such an apparition." – C.G.Jung

During the Cold War heyday of UFOlogy, even the President of the United States claimed to have witnessed something extraterrestrial floating in the sky. "There were about 20 of us standing outside a little restaurant I believe, a high school lunchroom, and a kind of green light appeared in the western sky," recounted Jimmy Carter when he was governor of Georgia in 1973. "This was right after sundown. It got brighter and brighter and then it eventually disappeared. It didn’t have any solid substance to it, it was just a very peculiar-looking light. None of us could understand what it was."

The post war UFO craze was nothing new, of course. "People have seen mysterious objects and lights in the sky since we first looked up, and that was, obviously, a very, very long time ago," Mark Pilkington, author of Mirage Men: A Journey Into Paranoia, Disinformation and UFOs, tells me. "How those things are interpreted is entirely determined by the prevailing cultures of knowledge, religion, mythology and folklore."

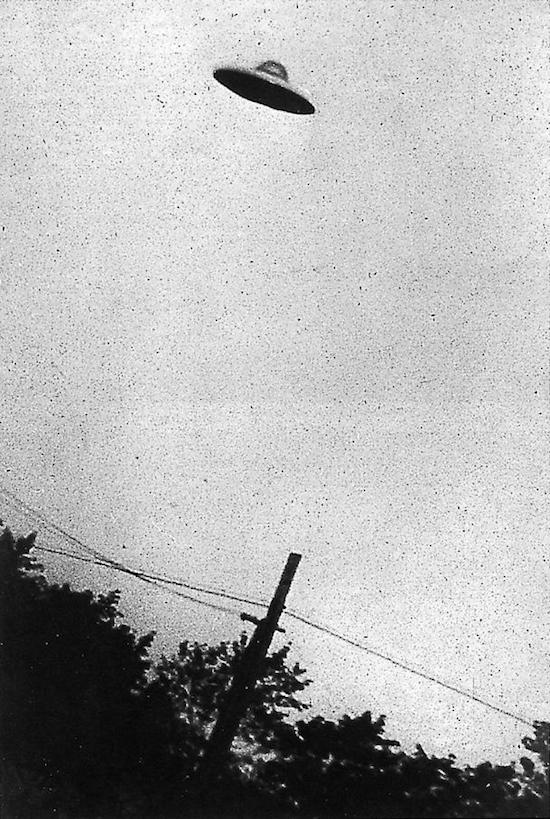

Jacques Vallée, who co-developed the computerised mapping of Mars for NASA, compiled a book full of word-of-mouth unexplained phenomena in his underground classic Passport to Magonia, with sightings stretching back to the Japanese Heian period ("On August, 989, during a period of great social unrest, three round objects of unusual brilliance were observed.") In his bracing 1959 analysis of the extraterrestrial phenomenon, Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen In The Sky, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung referenced 16th century pamphlets, yet even these were positively contemporary when compared with reports of "fiery discs" flying over Egypt around 1500BCE.

But shortly after World War II, UFOs became the gold standard paranormal activity, a bellwether that trumped ghost hunting or the pursuit of mythical beasts like Sasquatch, the Yeti or the Loch Ness Monster. These manifestations darting in and out of the ether caught the western imagination, given that they could be aliens or stealthy Russian spy planes, at once pulling on our paranoia and fascination with the exotic.

In this climate, UFOs became what Jung described as "a living myth". He wrote "we have here a golden opportunity to see how a legend is formed, and how in a difficult and dark time for humanity a miraculous tale grows up of an attempted intervention by extra-terrestrial ‘heavenly’ powers – and this at the very time when human fantasy is seriously considering the possibility of space travel". Times were superstitious too – "The heyday of astrology was not in the benighted Middle Ages but in the middle of the 20th century," observed Jung, "when even the newspapers do not hesitate to publish the week’s horoscope."

As the iron grip of religion eased people were now looking to the heavens for a different kind of truth. "As recently as the First World War, we still told stories about encounters with angels," John Higgs wrote in 2016 book Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century. "One example, popularised by the Welsh author Arthur Machen, involved angels protecting the British Expeditionary Force at the Battle of Mons. But by the Second World War, Christianity had collapsed to the point where meetings with angels were no longer credible, and none of the previous labels for otherworldly entities seemed believable. As a result, the strange encounters which still occurred were now interpreted as contact with visitors from other planets. The ideas of science fiction were the best metaphors we had to make sense of what we didn’t understand."

As movie special effects improved, so too did people’s appetite for space-age fantasy at the cinema. Three of the top 10 highest grossing films at the box office in the 1970s could be judged to have supernatural or sci-fi content, with Star Wars inevitably leading the pack. By the 1980s, six of the 10 Hollywood blockbusters were sci-fi related (while the three Indiana Jones films had a touch of the supernatural about them). Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was the biggest grossing film of that decade, and the 6th highest grossing film of all time (adjusting to inflation).

"Since the early 1950s, Extraterrestrial spacecraft have been the go-to explanations for mysterious lights and objects in the skies," says Pilkington, "and successive waves of TV and film entertainments have maintained that mythic dominance and exported it to pretty much every corner of the planet. I like to say that UFOs are one of America’s greatest cultural exports." UFO sightings are most frequent when popular fiction related to the phenomenon is at its most fashionable – they increased manyfold while The X Files was on air during the 90s, for instance. Are people more likely to see things when their minds have been stimulated by film or television? "Undoubtedly yes," says Pilkington.

"The stimulus does not cause people to ‘invent’ paranormal or UFO experiences," says Roger Marsh, communications director of The Mutual UFO Network (MUFON). "We do believe that the information about an experience, although fictionalised, causes the population to heighten their interest, and then try to report an incident. We quickly discovered that every time an episode of our television show Hangar 1: The UFO Files aired on the History Channel – for the first time or a re-run – our UFO reports dramatically increased. Even as those two seasons move into other markets around the world, we see an increase from the countries where the show is airing."

"The interrelationship between science fiction and UFOs is complex," says Nick Pope, who used to investigate UFOs and other mysteries for the British government, "and I speak as someone who’s had a foot in both camps, having also been a sci-fi author and a commentator on the genre. I don’t think having seen a sci-fi movie about aliens causes people to see UFOs, but it probably makes it more likely that they’ll report what they saw, because the release of a sci-fi movie creates a receptive environment where people feel they’re less likely to be ridiculed or disbelieved."

1980 arguably saw the peak of UFO activity, coming three years after Spielberg’s other paranormal blockbuster Close Encounters of the Third Kind had been to cinemas. Partworks like The Unexplained were all the rage, whilst Charles Berlitz and William Moore’s book The Roswell Incident brought the 1947 New Mexico conspiracy to the wider public for the first time. 1980 also saw Britain’s most notorious "visitation" at Rendlesham Forest in Suffolk. Pope, who worked for the Ministry of Defence between 1985 and 2006 – and specifically on UFOs between 91 and 94 – has gone on record to describe the Rendlesham incident as a "smoking gun". I emailed him to ask him how he could be so sure, given that he started working at the MoD five years after the incident took place.

"While investigating UFOs I had access to all the MoD’s previous files on the subject, including the one on the Rendlesham Forest incident. In parallel, I conducted a cold case review in 1994, and over the years I’ve met and interviewed most of the key military witnesses. The ‘smoking gun’, that tells us we were dealing with not just lights in the sky but a landing, is a Defence Intelligence Staff (the DIS is part of the MoD) document that contains an official assessment of radiation readings found at a landing site where there were physical traces of a heavy object having landed on the hard, frozen ground. This scientific assessment states that the radiation levels seemed ‘significantly higher than the average background’. In fact, they were around seven times higher."

If it seemed like we were drawing ever closer to ratifying an alien encounter of some kind, then something inexplicable happened, or rather didn’t happen. As the 20th century became the 21st century, interest in celestial apparitions of an unexplained variety suddenly dropped off, as did sightings. Even just a few years into the new millennium, UFOs felt very much a 20th century phenomenon.

In 2009, the Ministry of Defense closed the desk setup for the reporting of such anomalies, partly to save money after the credit crunch, and partly due to a lack of interest. In a terse statement, the department said: "Please note it is no longer MoD policy to record, respond to, or investigate UFO sightings," adding, "the MoD has no opinion on the existence or otherwise of extraterrestrial life. However, in over 50 years, no UFO report has revealed any evidence of a potential threat to the United Kingdom." Nick Pope told The Sun at the time that Britain was leaving itself open to terrorist attacks if there was nowhere to report "something unusual in our skies".

Many investigative organisations began shutting their doors or downscaling, and the Association for the Scientific Study of Anomalous Phenomena, or ASSAP, had a meeting in 2012 to decide whether to continue or not. In an article in The Telegraph entitled ‘UFO enthusiasts admit the truth may not be out there after all’, chairman Dave Wood said: "It is certainly a possibility that in ten years time it will be a dead subject. The lack of compelling evidence beyond the pure anecdotal suggests that on the balance of probabilities that nothing is out there. I think that any UFO researcher would tell you that 98% of sightings that happen are very easily explainable. One of the conclusions to draw from that is that perhaps there isn’t anything there. The days of compelling eyewitness sightings seem to be over."

I contacted ASSAP and they’re still a going concern, though Robert Moore who answered the email admitted "yes, interest in UFOs in the UK and Europe is now fairly low, and while UFO reports are still made, most are now resolved very quickly. BUFORA claims they only acquired one ‘high strangeness’ event last year."

In September 2001, two flying objects that were quickly identified as aeroplanes crashed into the World Trade Center, killing nearly 3,000 people and wounding more than 6,000. The trauma inflicted on that day had massive geopolitical and psychological repercussions that we have not yet fully recovered from. Terrorism was nothing new, but an attack on such a massive scale was unprecedented. Soon it became apparent that this was no one off; that the West was now "under attack". The present reality is that the train you’re travelling on, or the rock concert you like to attend, could as easily be a legitimate target as anywhere else on any given day.

"An event is officially ‘traumatic’ only if it opens in the mind a corridor to the apprehension of our essential helplessness and the possibility of death," wrote psychologist Martha Stout in her book The Paranoia Switch. "In this fashion, and in a big way, 9/11 officially traumatised nearly all of us." Soon after the tragedy came the recriminations, and calls for revenge, although against whom it wasn’t clear. "Speeches playing on our existing fears were made by candidates on both sides of the American political fence," wrote Stout, "and we accumulated a new vocabulary of menace to rival any apocalyptic novel: weaponised anthrax, Office of Total Information Awareness, orange alert, terrorist cell, dirty bomb, axis of evil, WMDs, shock and awe, perpetual war."

The War on Terror was a new kind of war too, a clash of civilisations largely driven by ideology. In an article in The Guardian in 2004 called ‘What happened to weird?’, Walter Furneaux, a clinical psychologist from Brunel University specialising in the paranormal and parapsychology, suggested that "to the public the idea of the al-Qaida terrorist, is almost like an alien. We don’t quite understand their culture, we don’t quite know what they look like, they live far away, and they are a perceived threat, in a way perhaps we thought aliens could have been."

Could it be that we were suddenly too busy looking over our shoulders to bother looking into the sky anymore? Had our brains replaced fear of one alien with another: the illegal alien, sat on a train looking suspicious, carrying a large rucksack? "I suspect that pragmatic and mundane concerns tend to trump extra-mundane ones," says Mark Pilkington. "If you’re busy worrying about how you are going to get your next meal, or whether you are going to get blown up by drones, then you tend not to be so concerned about what ET is doing."

He adds that technology is an issue: "Historically, the technological and flight capabilities attributed to UFOs tend to be just ahead of what we ourselves are capable of, and civilians are aware of. Certainly the military technologies we have now far exceed those attributed to ET visitors up to the mid-1990s. Also with the rise of the civilian drone swarms, I think people are more aware that there are multiple technologies of human origin that they might be mistaking for alien ones."

And then of course, there’s distraction. You only have to stand on a railway platform and observe commuters transfixed by their smartphones to realise people are looking at the sky less. And anyone who’s sat through the frankly risible Australien Skies or other UFO "documentaries" on Netflix will have endured bullshitting cranks and hazy orbs in the distance shot by shaky cameras that could as easily distant street lamps or lights from a teasmaid as intelligent life from outer space. In a world of Facebook and Twitter, virtual reality, gaming, cosplay, Pokemon Go, Bitcoin and immersive online cults, squinting into the night sky hoping that distant entities will deign to appear feels a bit like paranormal trainspotting in the ultra-connected 21st century. The ‘I’m loving aliens instead’ article Jon Ronson wrote for The Guardian in 2008 about his trip with Robbie Williams to a convention in the Nevada desert demonstrated how committed a believer has to be for what appears to be scant reward. Why would anyone in this day and age want to stare up at the sky all night when they can pop little green men to their heart’s content on a high-end games console?

Writing for Aeon in an article called ‘Why we have stopped seeing UFOs in the skies’, journalist and author Stuart Walton ponders on whether or not there were ever any UFOs now that people have stopped spotting them. "Once, the skies were refulgent with alien craft; now they are back to their primordial emptiness, returning only static to the radio telescopes, and offering the occasional meteor shower to the wandering eye," he writes. "It isn’t only flying saucers that have receded into history. They are being followed, more gradually to be sure, by a decline in sightings of ghosts, recordings of poltergeists, claims of psychokinesis and the rest." Walton refers to Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle for inspiration, and theorizes that it’s the bread and circuses of capitalism distracting us: "In the age of electronic mass media, when so much flashes around the world instantaneously, when video clips, in a telling usage, ‘go viral’, there should be no doubt about what is real and what isn’t. Yet the critical mass is no longer critical" (my italics).

Walton wrote that article in 2013, and four years later we have seen just what the uncritical mass is capable of. In a year of political earthquakes such as Brexit and Trump, 2017 promises further surprises in a new age of ‘post-truth’ politics. As The X Files hit the peak of its popularity in 1996 a Texan libertarian and conspiracy theorist called Alex Jones was starting out on public access cable TV, a hive for late night cranks who could easily be dismissed. He quickly moved onto radio and then the internet, with his shows picking up two million listeners weekly in the early 2000s. Jones’ broadcasts and his website Infowars were also dismissed by the mainstream media and the political establishment, though with hindsight we know that that was a mistake.

Jones believes in aliens, UFOs and accompanying government cover-ups. He also believes that 9/11 and the Oklahoma City bombings were inside jobs, and that the Sandy Hook massacre was a setup using professional actors as victims. "Sandy Hook is a synthetic completely fake with actors, in my view, manufactured", said Jones. "I couldn’t believe it at first. I knew they had actors there, clearly, but I thought they killed some real kids. And it just shows how bold [the establishment] are – that they clearly used actors".

You’d think this could be easily dismissed as the ravings of a madman, but people take Alex Jones and his ilk seriously. We now have to take Jones very seriously indeed; his legacy is assured as the part inspiration for the 2016 Republican campaign for the White House of Donald Trump. As Jon Ronson noted in The Elephant in the Room: A Journey into the Trump Campaign and the ‘Alt-Right’, Trump at the Travis County Expo Center, "attendees had basically come here for a Trump version of an Alex Jones show, a brassy, cathartic, crazy, dramatic explosion of anti-political correctness, a night of flipping the bird at the mainstream, a fuck you to the liberal elites for ridiculing or ignoring their concerns. This was evident by the large number of Infowars shirts and Hillary for Prison shirts in the crowd". The sloganeering, like the Leave campaign in Britain, was succinct catchy and deliberately vague: "make America great again"; "build a wall"; "lock her up"; while the more Trump ranted that President Obama had founded ISIS, Ted Cruz’s father was involved with the assassination of JFK, that thousands of American Muslims in New Jersey cheered the 9/11 attacks, the more traction he gained. It appeared the more outlandish the claim, the more voters lapped it up; as did the MSM while tutting disapprovingly as hits went through the roof. These brash, bloviating and blatantly populist proclamations of disinformation by a demagogue are a world away from the quaint and almost embarrassed account of an unidentified light in the sky by President Carter 40 years ago, demonstrating that in 2017, the truth is far stranger than anything fiction has to offer.

In this age of fake news disseminated online, large swathes of Americans believe three million immigrants were allowed to vote for HRC in California, Germans are being told Angela Merkel was in the Stasi and is the daughter of Adolf Hitler, and in France Alain Juppé’s charge to steer the Republican Party towards a moderate right path has been undone by false links to the Muslim Brotherhood. This erroneous sensationalism used to be the domain of newspapers like The National Enquirer and The Sunday Sport that we could easily laugh off. Nobody’s laughing now with Steve Bannon, founder of Breitbart, appointed Trump’s chief strategist and senior counsellor. The age of the dark enlightenment is upon us.

"If sensation is predominant, intuition is barred, this being the function that pays the least attention to tangible facts," said Jung. His friend, Sigmund Freud, meanwhile saw "our culture and civilisation as a thin veneer through which the destructive forces of the underworld could break at any moment", according to the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. If it’s beginning to feel like we’re about to enter our final chapter, then we desperately need some kind of deus ex machina in this narrative to deliver us from untold tragedy. If there really is intelligent life out there, then now would be a good time for our extraterrestrial friends to make an appearance, and save us from ourselves.