“Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, conformable.”

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation (1966)

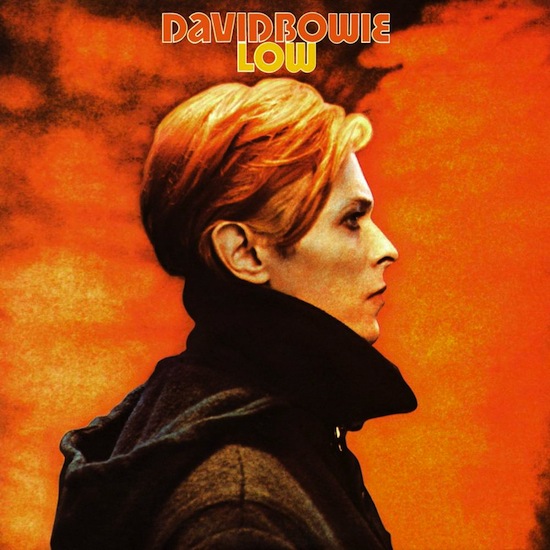

For David Bowie in 1976, both as an artist and a person, the only way forward was to step out of the ridiculous momentum that his career had acquired and start to regain some equilibrium from the clutches of his occult obsessions, fascist fascinations, peppers and milk, and prodigious amounts of gak.

Touring early that year in promotion of his album Station To Station – a merging of R&B, rock and the tip-of-an-iceberg of German Kosmische influence – Bowie performed in the bright austerity of nothing but fluorescent white light. It gave an imposing expressionistic feel in place of prancing around on six tonnes and 20,000 moving parts of hydraulic cherry picker and moveable catwalk as he did in support of Diamond Dogs two years previously.

This move towards a relative economy of content served as a prelude to an almost total eschewing of it. The sessions for Station To Station were allegedly a cocaine-fuelled spiral of tinkering with minute detail, much of what was recorded being unused or abandoned. As Bowie himself explained in an interview with Arena magazine back in 1993: “I would work at songs for hours and hours and days and days and then realise after a few days that I had done absolutely nothing.” But in Low there’s no sense of being mired, at least not musically. Recorded mostly at Château d’Hérouville in Northern France (the ‘Berlin Trilogy’ tag being perhaps a more conceptual bracket for those three albums than a geographic unification of them), Low has a sense of propulsion and constant motion, and an overarching idea of progress in terms of its collaborators and the atmosphere created by their collective presence.

As a fan, not only of Bowie’s but of pop music trivia itself, I find it hard not to devour the irresistible mythology of this period in his career. I love absolutely everything about it. The story is perfect. Leaving the psychosis of Los Angeles, fleeing to progressive Europe with accomplice Iggy Pop in tow, the melancholy of Berlin, a trans-Siberian train ride through Poland, the embracing of experimentation and of Brian Eno’s systems-based compositional techniques, Bowie’s rising from the ashes of addiction and obsession. The details of Low and its counterparts are so widely available and related to us in such microscopic ways that something like Adam Buxton’s parody of the recording sessions (brilliantly animated by The Brothers McLeod) is hilarious more or less entirely due to the strength of its accuracy of reference.

Given this, one has to wonder what the point in re-evaluating this album is when, 40 years on, the layers of interpretation slung at it have left such a sludgy film over every inch of it. To listen without knowing, to relate the content of it to our own lives, or to simply enjoy it on the basic principle that it’s brilliant just because, now all feels like an insurmountable task.

Is it important to take into account Bowie’s shattering personal life ahead of and surrounding the production of Low? Does it matter that you are able to draw parallels between certain lyrical refrains and Bowie’s previous interests in esoteric spiritual and political methods? The level to which track-by-track analyses of Bowie’s work, especially of the Berlin era, create a very male and anorak-y exclusivity to its understanding is kind of absurd.

Perhaps there’s something in wanting to place yourself in the historic context of an album that makes you feel like you were there. No doubt the sessions for Low would have been interesting ones to be a fly on the wall for. But historic context is not the same as interpretation. If we take, for example, ‘Warszawa’, the anomalous centrepiece of Low, there’s somewhat of a conflict that exists in the account of its composition and the common interpretation of it as a piece.

‘Warszawa’ was almost entirely the work of Brian Eno who was working mostly alone towards the end of the sessions for Low, Bowie being away in Paris for a court case. Bowie returned and, impressed with Eno’s work, added the vocal of an invented language, apparently influenced by an LP of a Balkan boy’s choir he’d picked up, perhaps while on an extremely brief visit to Warsaw on a train from Zurich to Moscow via Poland in April of that year. But this brief visit coupled with the title of the track seems to invite many explanations for the source of the language or the reasons for doing so. We shovel unnecessary layers of explanation onto things to validify them. It’s hard to accept that Bowie quickly added this vaguely gibberish vocal line on top of Eno’s composition. It’s as if it needs to be defended rather than to be experienced. Chris O’Leary’s forensic ‘Bowiesongs’ blog on this, and every other song on Low, delves to these extreme depths. So, too, does Hugo Wilcken’s 33 ⅓ book on the album, Peter Doggett’s The Man Who Sold The World: David Bowie In The 1970s and Thomas Jerome Seabrook’s Bowie In Berlin: A New Career In A New Town, to name a few examples. All of these are fascinating and often well written historical accounts on the background of the recordings, but these details start to overshadow the experience of the works themselves.

Low is a brilliant album because, through its production alone, it can transport the listener to certain frontiers of place and thought in a very powerful way. The expert musicianship and the composition of its pieces allowed the players to circumvent their habits and thus form a new musical language, as was allegedly Bowie’s intention. To step out of the momentum of what they knew.

Low is also evocative of many things, but it isn’t definitive. Most tracks fade in and out of view with no real beginning or conclusion, they could be of any non-fixed duration beyond the timecode printed on the sleeve. Of what lyrics are there at all, they are rarely the central focus. The whole thing challenges a classical notion of a top-down creationist approach to making work – the idea of the heroic singular artist receiving divine inspiration – and instead establishes Bowie as a centre of gravity for many brilliant minds and influences to orbit around.

But the inability to separate the mythology with what is simply happening there before us traps us, the audience. This same obsessive interpretative appetite has, over time, created a landscape, at least in the wider spectrum of contemporary pop music, where most albums are now required to perform an act of conceptual importance – usually something that fits inside a topic of the zeitgeist – or to be of a searing confessional nature. We now expect our albums to come pre-loaded with context, vying for importance amid the competitive land grab for think pieces, and there’s a sort of latent expectation that our artists go on these personal journeys to legitimise the work they create and the experience that we might gain from it.

Conversely, what if we were to look at the general (and I do mean more in terms of its mainstream appeal) indifference to Brian Eno’s ambient projects? By contrast with Bowie’s mainstream success, although Eno’s position in the pantheon is well established, we’re perhaps only now starting to see an acceptance for the intentions of his ambient work, rather than a perplexity towards them. Audiences have long struggled with the more ‘functional’ aspect of Eno’s post-1975 work since it defies easy interpretation in many ways, not least because there are no words involved and that the details of Eno’s private life are fairly secret to us as an audience, nor are they important. It’s hard to accept work that is not narrative or autobiographical, as it’s these traits that make them apparently human. We have very little evidence with which to apply any meaning or give a sociological reading of Thursday Afternoon or LUX beyond the idea that they are beautiful as they are functional. We’re so obsessed with the personal narrative behind things that Roxy Music will scarcely not be mentioned next to Eno’s name even 45 years after he left the group that he only made two albums with.

This isn’t to say we shouldn’t think about what works mean in wider contexts. It’s important that we do. But there seems to be a lot of unattainable reaches for some absolute truths. I have only recently come to this realisation. Last year I wrote about the band of Montreal on this very site, and my obsession – as many other fans of the band will likely share – with the personal details and interweaving of confession and autobiography in Kevin Barnes’ work was one of my central attractions to them. Barnes has, unfortunately, set this precedent for himself though. When his work is merely allegorical or fictional now, you feel like you’re being short changed. By this logic, I want Kevin Barnes to suffer forever so that he may make brilliant work that ‘means something’. What a ridiculous standard to set for someone.

With Bowie’s final album, Blackstar, there was but a small window where the weight of interpretation didn’t burden the brilliant work that was already available to us without it. Upon the announcement of his death two days after its release, all the lyrical signs and hints on mortality within the songs quickly subsumed the focus of the work. It now feels impossible to discuss that album without the need to refer to the fact that it so heavily regarded the author’s demise. In the actual death of the author, the death of the author felt most prevalent.

But let’s suppose for a minute that Blackstar was not Bowie’s final album, as indeed producer Tony Visconti has hinted may well have been the case. Would the lyrical messages be redundant if it had turned out to be his penultimate antemortem recording? Could we accept it on a compositional level despite these things? At the time of writing this, it’s been reported that Bowie only knew that his cancer was terminal three months before dying. Does knowing this rob us of its effect? Do we feel cheated?

I don’t think so at all. Bowie’s death itself was enough to make us consider mortality in a unique way. In 2016 we all became far too accustomed to waking up to a grief-stricken reality more repeatedly than most of us can remember. Bowie’s passing came first, at a time when we weren’t quite as desensitised to this as a regular event. It required such a public outpouring of grief and loss, but it was felt in the most joyous of ways. I may have sat there crying my eyes out and drinking wine in front of endless YouTube rabbit holes, but there was a celebratory air to this grief. It was a new or different way with dealing with death, albeit regarding someone very few of us had any connection with beyond his brilliant work. Of course Blackstar was coloured by his passing, but I don’t feel the lyrical references made this more real or valid by being true or not. The idea of his spirit rising and drifting felt entwined in the final devastating guitar passage of ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’, a song which samples ‘A New Career In A New Town’ from Low, as much as him singing “look up here, man. I’m in heaven” on ‘Lazarus’.

Low remains, in my memory, a moment of pure discovery that most other records have failed to surpass. Its jarring experimentation opened doors for many artists, especially as it was a gesture performed by one of the world’s most popular artists at the time. It challenged the idea of what an album could be, in its structure and in its ingredients. It also served as the blueprint for ‘the reinvention’, the kind that, to give one example, Radiohead would undergo 23 years after Low on 2000’s Kid A. In the nature of its production it serves as an incredible example of an artist at the apex of their popularity who was able to confound the expectations of his audience despite trying circumstances. Beyond this, the only interpretation of it that matters, really, is that of your own.