I’ve been waiting patiently for this book ever since its editor, the poet Sophie Collins, contacted me about it nearly two years ago. Currently & Emotion, a collection of innovative translations of mainly poetry, is independent publisher Test Centre’s latest release, and one that I and many others welcomed with real excitement and awe.

By minor coincidence, Sophie and I were both encouraged to apply for the same PhD in poetry and translation in the same year a few years back: I didn’t apply; she applied and was accepted, with the anthology a component of her project. On hearing shortly afterwards that it was Sophie who was studying for the PhD I couldn’t help but follow her translation activism. I have felt incredibly encouraged watching her use her platforms for the same motivations I believe in: changing people’s perceptions of what translation is and can be and highlighting the socio-political nature of translation and translations. I went to the Currently & Emotion evening of readings and panel discussion that took place at the ICA a year ago, as well as the anthology’s recent launch at Hannah Barry Gallery in Peckham, and both times left inspired by the depth of thought and conviction behind everything Sophie does.

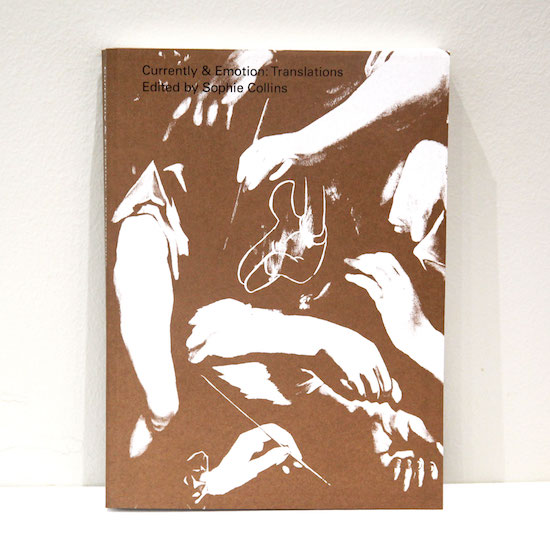

Currently & Emotion has just been named a Book of the Year in the Times Literary Supplement, so perhaps you are wondering, or even asking out loud, why we need something as seemingly niche as an anthology of experimental translations right now, in the middle of everything else that’s going on in the world. At first glance, Currently & Emotion may appear to be a weighty, dulled-bronze object of beauty, or simply an ornate-looking but accessibly-priced (as is a mark of a Test Centre publication) collection of multiple creative approaches to translations of poetry and other texts, but it is actually a weaponised manual, a magical lexicon, a deciphering tool, that will help unlock the nature of all mediated communication.

There are translations: led by spellcheck in Microsoft Word; made by shooting the original text with a gun; that undermine the original as a ‘remarkable failure’; as feminist readings through curatorial and appropriative approaches; that exist in the public realm in place of the censored original; as experimental ‘sister’ to the more traditional ‘older brother’; denying neo-colonisation-via-translation; expressing the most elemental parts of the original; as ‘inconsistent’ as the original.

These experimental translations, that is, translations that see form as integral to the ‘success’ of a translation and don’t necessarily prioritise or believe in the integrity of passing on linguistic content, are not only feats in experimental writing, but also illustrative of the practice of translation. They illuminate what’s at play behind the scenes. They take translation approaches to their extreme, or complicate the presentation of translations to reveal the subjective nature of translating and question the second-class status of translations. They confront the original, they set the author free, and can even make texts more powerful through their translation.

One of the clearest ways of explaining why this anthology isn’t some kind of literary luxury is the quote from translation theorists Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere from the book’s introduction that starts ‘[a]ll rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics and as such manipulate literature to function in a given society in a given way’ and ends that ‘in an age of ever increasing manipulation of all kinds, the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.’

Sophie Collins’ introduction positions this anthology at the intersection of translation and feminist theory, born of powerful movements that critique the foundations and normalised literature and translation practices through ‘the persistent questioning by a growing minority of a culture built on patriarchal beliefs and forms of expressions and the seeking of new forms and languages of expression’. The title itself refers to both the fact that translations are called into being in a specific temporal context for a purpose, and a turn towards ethical and empathetic translation. Through exploring what is happening in re-writing or translation we can see how it often becomes a hierarchical process and symptom of (cultural, patriarchal, selfish) domination, but has the potential to be a process or expression of (cultural, feminist, surrendered) empowerment, or even a negation of the hierarchal process entirely.

The anthology includes interlingual (between two different languages), intralingual (between two forms of the same language, otherwise known as ‘rewording’) and intersemiotic (between two mediums, like from text to image) translations – though we are invited to question these firm categorisations – and incorporates an awesome and culturally diverse range of texts in terms of subject-matter, intention, practice and process. Four stand out contributions for me were from Holly Pester, Khairani Barokka, Chantal Wright and Vahni Capildeo.

The two poems from Holly Pester’s Katrina Sequence were formed by Pester listening to ham radio operators’ dialogues during Hurricane Katrina on YouTube, reciting what she heard into a dictaphone, transcribing what she thought she said and then compressing the file.

[…]

this is papa

there’s something going on i

don’t know what kind of call that is

can you give me some names some information

my name is Douglas

i’m at the hospital in Mississippi

ok Douglas go ahead i can help you

ok you can get the equipment back up and ruining

[…]

- from ‘THIS IS PAPA’, Holly Pester

Using an unofficial source of information, which she then rushes through into a faulty transcription (‘ruining’ instead of ‘running’, for instance), is a manifestation of a ‘selective hearing’ as an ‘implicit comment on the media’s coverage of Hurricane Katrina and George Bush’s government’s fatally delayed response.’

Khairani Barokka, whose Braille and text poetry-art book Indigenous Species will be published by Tilted Axis Press this week, is also currently co-editing Nine Arches Press’ anthology of UK-based D/deaf and disabled poets. Dedicated to exploring the intersection of translation and disability, what Okka terms her ‘lateral translations’ of folk songs she heard sung by women in Bori Village in Rajastan into photographs are accessible to and for the enjoyment of a D/deaf readership while avoiding the typical up/down hierarchy between languages due to perceived socio-political/cultural standing altogether. Okka is clear that making the translations accessible isn’t the be all and end all of her translations, but to add weight behind the actually positive reading of all translations as imperfect and that the world can be understand in a multitude of ways.

Translator of German literature Chantal Wright’s ‘thick’ or annotated translation of Japanese-born Yōko Tawada’s story ‘Portrait of a Tongue’ appears in a left hand column, while a right hand column has her commentary on her translation, including cultural idiosyncrasies of Berlin and North America and explaining a linguistic misunderstanding between two characters. This commentary is set off, for instance, by keeping an ‘untranslatable’ German word in her translation leading her to explain its different interpretations. Her method is partially a taking up of Vladimir Nabokov’s cry for footnotes with translations to be dominating and ‘copious’. But it is also accentuating the fact that to simply translate Tawada’s word games, puns and words with multiple meanings without further explanation would do a disservice to a story that is grappling with the wonder of language itself in order to share the immigrant experience, much like British-Chinese author Xiaolu Guo does in her novel A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers.

Vahni Capildeo’s contributions to the anthology – like Pester’s and Okka’s – are intersemiotic translations of a museum piece and a photo in the form of two poems from her Forward Prize-winning and (at the time of writing) TS Eliot Prize-shortlisted collection Measures of Expatriation. Instead of using an image or object (in the case of ‘Snake in the Grass’: a sword with a wavy blade) as a metaphor, or speaking on behalf of an ‘ostensibly silent’ artefact, Capildeo lets the sword, an exhibit in the Ashmolean Museum, speak for itself:

[…]

Do not shun me. I am not sleeping.

Glass is the least security. My kind’s for re-use,

willing to coil cold in the earth

till each deadly resurrection through your changes of nation,

till your kind hand comes and the smith repairs us.

Slide your eye into the wave and wind of me.

Forget your wife, if you still have one.

The two of us decide who’s for the taking.

Bring me your son, blossoming in his cradle.

Introduce us. I have a name.

[…]

- from ‘Snake in the Grass’, Vahni Capildeo

Remarkable in its acute self-awareness, the second poem, ‘Pobrecillo Tam’, came from Capildeo’s self-directed annoyance that she had automatically connected a photo of a game of chess playing out in front of skyscrapers as depicting America rather than, say, her native Port of Spain or somewhere in Eastern Europe, and expresses internalised cultural dominance through a migrant subjectivity.

This collection should be considered as a submergence into intense dialogues, passionate responses and protests; it makes possible the revelation that if these translations ‘misbehave’ to be the best translations they can be then we should critically (re)consider how we evaluate the worth of all translations.

Of course the contributions, introductions, and additional essays (by Erín Moure and Zoe Skoulding) are absorbing and engaging, but what lures you in initially is the spacial quality of the book, with its bronze, fluoro-red and black demarcations and matching bookmarks. It’s like entering a surreal maze of language that disorientates through its upending of pre- and misconceptions and truly surprises through real socio-political power. I’m looking forward to spending more time lost within it over Christmas, and for a long time to come.

I asked Sophie a few questions about the book over e-mail in the week of its the London launch.

How did Currently & Emotion initially come about?

Sophie Collins: While I was doing an MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia, I was shown an incredible opportunity at Queen’s University Belfast by my then translation tutor Valerie Henitiuk. Queen’s had created a new research position for a postdoctoral student to look into poetry and translation, and to be supervised by Lawrence Venuti – I think you considered applying for this too? I was surprised to be accepted, and straight away felt a responsibility to engage fully with translation theory, to familiarise myself with the latter as a discipline before embarking on a translation project (the PhD is both a critical and creative one). Translation theory appeared as this huge and intimidating thing, but it was also beguiling, and would become very important to me as an overarching critical framework. (Conversely, I recently heard a poet describe, or rather dismiss, ideas around translation as ‘an abyss’ when asked about his work with translation during a post-reading Q&A.)

The more I learnt about translation theory and practice during my PhD research, the more I became frustrated with how translation is perceived and discussed by writers, literary critics and readers. I felt that the way to confront this problem of representation was not simply to write and publish academic articles about it, but to create something that the literary world would want to read and engage with – both aesthetically and critically. An anthology of exciting contemporary work that also offered all readers routes into thinking about how translation is a highly political act and mode of cultural and literary criticism, how it shapes and affects our reading and understanding of other (literary) cultures, seemed like a good place to begin.

Who is your ideal reader?

SC: The book is one that wants to change minds and develop popular thinking on translation, which means that the ideal reader is possibly someone who hasn’t thought a great deal about translation before, and who discovers a new dimension of thinking as a result of seeing the anthology – the same as me at the time of first reading Venuti, Sherry Simon, Gayatri Spivak and others. But then again I’d be ecstatic to think that someone who’s knowledgeable in translation matters could find some enjoyment, even some fresh ideas, in the material of the book. I think that to someone like that, the concepts will be familiar but some of the work might be new, coming as it does mainly from small presses.

What were the greatest challenges and pleasures of creating the book?

SC: Everything about the creation of the book was both challenging and pleasurable! It was a strangely intense experience putting it together with Jess Chandler at Test Centre. Looking at it now is a bit like looking directly at the sun. Securing rights for all of the material in the book was possibly one of the most arduous tasks for us. The prefaces that accompany each translation were also quite an undertaking. It was a pleasure to have the support of all of the contributors, however, and to discuss their work with them (directly, in most cases).

With so much of your time spent on your poetry, your PhD and editing, do you find the time to also translate? If you do, what are your present or future projects?

SC: I’m working on some ‘looser’ translations of poems by Polish poet Małgosia or Małgorzata Lebda. I’ve also been doing a bit on poems by Lieke Marsman, a young Dutch poet. Having grown up in the Netherlands, Dutch would be my ‘other language’ (I hesitate to say ‘second language’, though I’m not bilingual) and I feel there is a lot of really brilliant work in Holland. I’m also interested in translating a novel from Dutch, and am currently thinking about and discussing this with certain people – maybe translating a novel will teach me how to write one too?

What are you most excited about in all things translation currently?

SC: I’m very excited by what universities are doing with translation as a discipline, which is growing and growing in so many ways, including in terms of its influence on more visible lines of study (like comparative literature – see Emily Apter’s books for instance, including Against World Literature). ‘Translating feminism: transfer, transgression, transformation’, taking place at the University of Glasgow, is a really important and inspiring research project.

Lydia Davis’s engagement with Dutch literature is surprising and exciting to me. I was gobsmacked and a little irrationally jealous to see her mention De Avonden (The Evenings) in an interview with Asymptote. As she writes, the book by Gerard van het Reve is a classic in Holland and ‘portrays just ten days in the tedious life of a clerk who lives with his parents’. There are ten chapters. Each chapter is a day, and the whole thing takes place in winter, across Christmas and New Year’s Eve. There are lots of strange and disturbing dream sequences. I first came across the story in its graphic novel form (rendered by Dick Matena) in my dad’s study when I was not quite a teenager and became kind of obsessed with this thing I saw as an esoteric object. I was so entranced by it. Later I essentially plagiarised sections of the story as a first year Creative Writing student. I just found out Pushkin Press have published an English translation.

Certain poet-translators’ words about translation continue to excite me – Don Mee Choi’s and Linh Dinh’s, in particular. They express different aims for, and critical perspectives on, translation, but they are both particularly forceful and caustic – qualities that I respect and enjoy, and am personally drawn to. I’m really looking forward to Choi’s translation of an interview with the Korean poet Kim Hyesoon in the forthcoming issue of Modern Poetry in Translation. Her translations of Kim’s work in Currently & Emotion are phenomenal.

Also Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia translated by Ann Goldstein. I’m about halfway through, and so much of what Ferrante wrote – mainly privately, in letters – in the ’90s and early 2000s accurately anticipates our current political situation.

Sophie Collins is co-editor of tender, an online journal promoting work by female-identified writers and artists. Her poems have appeared in magazines, anthologies, newspapers and art books, and in the first instalment of the newly revived Penguin Modern Poets series with Anne Carson and Emily Berry. She is an artist-in-residence at Glasgow Women’s Library, where she is researching and writing a text on shame to be published by Book Works in 2017. Her first poetry collection is forthcoming from Penguin.

Jen Calleja is a writer and literary translator from German. Her debut poetry collection Serious Justice is published by Test Centre, and she is currently translating a novella by Kerstin Hensel and essays by Wim Wenders. She is index artist in residence in Zurich working on her first novel, translator in residence at the Austrian Cultural Forum London and editor of Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt. She plays in Sauna Youth/Monotony, Feature and GOLD FOIL.