Gee Vaucher is one the most significant political artists, managing to have her work widely circulated but often overlooked in its own right. While primarily known as a visual artist, her work is of great interest in terms of political philosophy and creative practice. Vaucher is best known for her work with the band Crass, but has an extensive range of work from the 60s until present. This includes working with members of Fluxus, paintings, film, collage, sculpture, design work, and extensive collaborations that have helped to facilitate and create Dial House, a collective home and arts space in Epping, for nearly 50 years.

While it is easy to see Vaucher’s work in relation to protest art, it is more than that, particularly in how it employed ultra-realistic gouache painting techniques to affect a kind of Surrealist displacement. Vaucher’s work during the past twenty years has explored more personal themes, as well as the relationships between not only humans but also animals and humans. It is only recently that it has become possible to gain a fuller sense of the scope of Vaucher’s work through important and timely re-printing and re-releasing of some key materials that had been previously unavailable.

Vaucher’s work within Crass and Dial House helped to ferment and foster a DIY spirit in artistic performance and political organising. Rather then relying upon large corporate records labels to distribute their productions the members started their own production and thus were able to exercise much more influence over the conditions of their work and its distribution. This was hugely influential and took place before the rise of independent record labels in the UK. Vaucher’s work is an amazing and inspiring example of the ability of groups of people working together to find ways to communicate and express themselves, and thus to find new ways of organising and living.

You’ve worked with a number of people on various projects, and with some people, like Penny Rimbaud, for many years. How do you approach collaboration?

Well, it’s not unless somebody asks me, otherwise I just get on with my own work. But if somebody asks me to collaborate with them, then I consider it in every way, you know, the person, the project, the time, what it’s trying to say, and then we move from there. I don’t look for collaboration; collaboration comes to me. It’s kind of easy in that sense. It’s very rare that… the only time I really seek collaboration is during an exhibition where I will ask Penny to perform. But he collaborates with great sensitivity even though he performs his own thing, obviously it relates to what’s on the wall, but it adds to and broadens the voice of the show. But it’s rare for me to initiate collaboration. But I suppose you could say that Exitstencil is a way of collaborating.

How does the context in which your work circulates affect your approach? Is that something you consider?

No, I don’t really. Obviously, there’s my own work. I do what I like in terms that I choose the subject, or it chooses me, and it gets translated by using the best medium that will convey the work. It can evolve through sculpture, print, paintings, drawings, film, whichever way I feel it’s going to say it the best. Then there’s work in the past that I’ve done for a living, where the subject is given. But even then I have to have free range once I have the basic subject matter. Once I have that, especially now. People ask me to do a job because they must know how I work, what they’re going to get, which is not a ‘pretty picture’. I don’t even accept the job unless I can see the words first, especially if it’s for a record cover, though I rarely do them these days. I can’t spread myself that thin anymore so I have to say no, but in the past I would say, yes, sure. I’ll think about it. Send me the words. If the words rang a bell, I would do it, but if it didn’t, I wasn’t interested. That’s the way it usually worked.

Was it more possible to take that approach in what work you chose to do, or didn’t do, because of living in Dial House?

Yes and no. Yes because I didn’t need to earn a lot to survive, and no, I chose who I worked for on my terms. There’s been a couple of times where it’s been big money, because it’s a big band, but then I liked the people and I knew that they were genuinely trying hard to say something in a world where it was very difficult to do so, because they’re were signed to a big label. So I think, okay, I’ll try and do my best for you but you’re going to have to pay the price, because they can afford it. They are on a big label. I’m not going to do it for nothing. Most of the time though it’s been for small bands and it’s a fundraiser and I don’t get paid, but I don’t mind. If I really like the words, if I really like the people and think they’re trying to do something, which is all judgmental of course, I don’t mind doing it for practically nothing, but usually I ask for something ridiculously low because I think it’s quite good for the band to have to find the money. But then I think in a way it helps people to deal with money, money can create enormous problems between people and enormous arguments, it’s viscous.

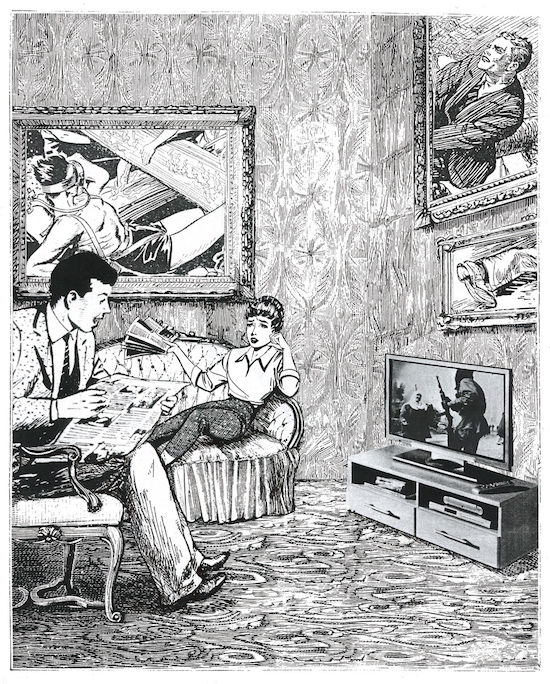

Illustration for inside poster for Crass Penis Envy album, 1981 Collage and ink. 290mm x 210mm

One thing I was surprised about when I arrived to Dial House, it wasn’t what I expected. I grew up on a farm and yet I always associated punk and political arts with an urban context. But arriving at Dial House it actually looked a lot like where I grew up.

Yes. I don’t think we could have operated Crass without having somewhere peaceful to come back to after each tour. I personally could never have done Crass out of a squat. I certainly needed the peace. My ideas come to me when I’m gardening. I love gardening, that’s where ideas flow. I don’t think I could survive very well without the garden.

It is one of the most wonderful gardens I’ve ever seen because it doesn’t feel overly manicured, everything has an organic order to it, but one that seems like it evolved like that rather then being planned.

Yes it has evolved, and many people have contributed to it, which is nice. And not only people who are still alive, there’s a lot of ashes of friends scattered in the garden through the years, there’s a lot of good energy around, good spirits.

I can imagine that. I was listening to an interview that Penny did with V.Vale [broadcast in August 2013 as part of V. Vale’s series RE/Search TV: The Counter Culture Hour.] and he was talking about being able to see a particular piece of land, develop it over fifty years, and how through that you get a sense of a place that you never have otherwise.

Very much, it’s our spiritual home. We’ve been here for nearly fifty years. It was found abandoned. Everything has been built and designed, well, it designs itself really, it’s very demanding. You follow the landscape, follow what’s there and see what happens. Yes, it’s a place where we feel at peace. Even as a kid living in the East End of London, we had a small garden, and that’s where I spent my time, touching the earth. It’s very important for me. I had two years in New York, but even then I started a garden on the roof. Because it’s life isn’t it? It’s about sowing life, and seeing life grow, especially if you’re down and depressed for some reason. That’s what we find with a lot of people that visit Dial House with problems. I give them a job in the garden because it helps them to ground themselves again. It’s meditative. It’s hard work. It gives you time alone. There’s no argument with the Earth, it only gives.

The garden at Dial House, August 2016

When I first saw your paintings in person I was struck by for years I had thought of your work as collage and thus didn’t realise that actually a lot of the work was done in gouache. It’s so detailed, hyper-realistic, and small scale. Seeing the work in person blew my mind. How did you develop that particular approach to your work? Is it something that you developed when you were in art school?

Not really. I don’t know why I developed it like that. The very first paintings that I did in that manner, in that tightness, were for a children’s book. You can see some of them in the newest edition of the Crass Art and other Pre-postmodernist Monsters book. I think it was then that I went on to develop it for heavier subject matter because I could see people were very attracted to it. They would be drawn in to the technique without seeing the subject matter, so didn’t have a chance to say “oh, I can’t look at that”. I don’t paint like that now. I can’t. I can’t in lots of ways. I don’t have the patience. I don’t want to restrict my head in that direction any more. I’ve moved on. My eyesight wasn’t so sharp, so I couldn’t physically do it anyway. My eyes are better now, but I still don’t want to paint like that again.

It’s sometimes suggested that there is a shift in your work during the 1990s, a shift in approach and subject matter, where it becomes more metaphoric and more personal.

If you say so. When Crass finished in 1984, three members of the band were faced with ailing parents. Three eldest members in the band. We all had parents that were getting very frail and needed caring for. We all had to deal with that in our respective ways. I personally had come to the point where I couldn’t say any more about war and governments. I didn’t want to continue in the same way. I thought “Well, I’ve said it, I can’t say it any better than I’ve said it already. I can’t and I don’t want to try and reach out to the rest of the world at the moment, I just want to deal with what’s in front of me now, ailing parents, local village disputes etc, what’s on my doorstep now. I wanted to focus on things that I could possibly have an effect on locally, because I didn’t feel I could say anything more about the global situation. It’s always the same old shit anyway, isn’t it?

It’s interesting to think that there is a parallel in that to some of the early Public Image Ltd materials, which are about John Lydon dealing with the death of his mother, and thus are much more personal.

Oh, yes. I think you have to. Having spent nine years projecting and taking in the whole world to try and understand what the hell is going on? You can only say so much and felt I couldn’t do any better than I’d done. That’s not to say I couldn’t now or that I’m past caring, but at the time I just wanted to bring it closer, look at what was in front of me and demanding attention like ailing parents.

llustration from A Week of Knots: Tuesday – Father, 2016 Collage. 330mm x 230mm

One thing I find most interesting about Dial House is the many different projects that have come in and out of it over years, each with different collaborations developing over time, then reforming and moving in another direction.

Yes, and some people have run with that and gone to the other side of the world to develop their own voice. It’s all very interesting and very rewarding in that sense, that people have run with ideas and taken it places we would never have taken it, lovely.

It’s a bit like the garden then, let’s see how things lie, how things develop?

Yes I suppose it is. People come into Dial House and you give them a job to do, and they do it – but often go about it in a very different way to what you might. Living somewhere like we do, it’s something you have to learn and allow people to go about things differently. I’m not always good at it and poke my nose in! Obviously you have to give some directions especially about gardening and make sure that people understand what is a plant to be left, and what is a plant to be taken out. We’ve had many accidents. Because for me it comes as second nature with plants, you forget that people don’t know one thing from the other, they really don’t. Somebody dug up the whole asparagus bed, which was twenty-five years old. It takes about four years to get good asparagus again. I had one plant left. I said “okay, well never mind. What’s done is done.” I put a new lot in last year.

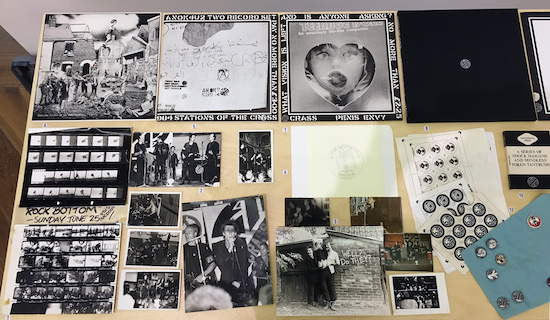

Selection of Crass materials and ephemera

How do you understand the potential of political art to change the world, to change the way we relate to each other? It seems that often, people expect social conditions to change quickly rather than being transformed over time, like in your garden.

I think it goes without saying that creativity of any kind has enormous influence, from the obvious, music, theatre, photography, to the less appreciated. But you can start with a populist artist like Banksy who makes political statements on walls. For me I think he makes it too throw away sometimes, too much of a joke, it becomes entertainment, too easy to laugh at and just walk on by, plus of course, the added hysteria that now goes with it. I’m not sure what to think, I don’t know what lasting influence this sort of graffiti on walls will have. Then you get propaganda posters promoting war and a reaction of posters calling for peace, so obviously it must affect people. Images with words can have great power and can either move mountains for the good of all or destroy. Yet people seem to forget that everything we look at, we make use of, has been created, designed, from a bar of soap, to a building. That’s what successive governments understand, the power of creativity and how it affects the way people think. Maybe that’s why they try to crush it out of schools. When you look at creativity in schools in Britain now, you know you couldn’t obliterate it more if you wanted to. I know it will change, but a whole generation of young people are being forced into learning stuff they have no interest in or aptitude for, for damned exams. They are not taught something useful like how to survive, how to realise that creativity has many forms and could save their lives. It’s absolutely tragic to impose so much dead matter on a child and then expect them to find their place in world. No wonder people feel lost and incapable of dealing with so much in life. The government knows that and it can sway people’s minds very easily to it’s advantage.

That’s what I find most compelling about punk, more so than the music itself, is the DIY aspect. It inspires people to say “oh, I’ll can do something myself, together with my friends we can make something” – and that’s important, regardless of what’s produced or whether it’s the most aesthetically compelling outcome.

That’s right. That’s what punk was to me. Who cares if you can’t play an instrument, just have a go. Only two people in Crass could play an instrument. Andy didn’t even know how to hold a guitar, and he never did, but what did he do? He held the guitar his way. He couldn’t play different notes so strings were all tuned the same so he just played chords, sliding his hand up and down. Whatever it was, he had great rhythm, and he made that rhythm the way he could, but he couldn’t play guitar in a traditional way. That’s what the whole movement was about for me, just do it, find your own way. Until you try, you don’t know, do you? Make it your own. To me that’s still the most important thing, because it’s so easy to put yourself down and be put down by government, school or by family. It’s so easy for forces outside of you to stop you in your tracks and then you lose confidence, you lose your way, and you end up not creating anything. Everybody’s creative. Every child is creative. Find your true love and gift, even if it’s making a fine cup of tea for others.

In a certain way some of the ethos of DIY punk was trying to recover a sense of community and belonging that existed before, but had been fragmented.

Yes, that’s right. That’s a major problem for a lot of people, that they don’t feel they’re part of anything any more. They don’t feel they belong, they have no use. That is the uprooting of people. That’s why some get into terrible things, terrible trouble, and then a physical problem arises on the streets. Drugs, drinking, violence – anything to obliterate the pain of not really belonging. That’s one of the biggest problems in many parts of the world now, this sense of not being able to contribute and having no community. And Thatcher had a big hand in that, especially in the working class areas. She started selling off the council houses. Suddenly the worst aspect of council house ownership became “Oh, we own ours, let’s put up a wall.” The row of terraced council houses where my mother lived and where I was brought up, had back gardens, There was a gate in the fence, to the next garden so you could walk through and chat with your neighbour. “Oh, you need some sugar, hang on a minute, I’ll get some.” The street I lived on was filled with people who had been moved out of London during the war. As you can imagine there was a lot of comradeship and sharing, if you didn’t share you didn’t survive too well after the war. But suddenly in the 70s, people had an opportunity to buy their council house, they put tall fences up and somehow the separation began not just of gardens but of people and you didn’t know who your neighbour was any longer. I’m not saying that people shouldn’t have had the chance to own a house, but the way it was done by the government was at fault in many ways.

My mother was very upset one day when I was visiting. She was in tears. She thought that because the neighbours had bought their house and then put in a high fence, they didn’t like her. She couldn’t understand why somebody would want to do that because nobody had ever done that before. Neighbours were always popping across the garden. She just couldn’t understand it.

I said “mum, it’s not personal, they’re newlyweds, they just want to be private, that’s all, it’s not a comment on you.” But she couldn’t understand it and the newlyweds had no idea what they had done. It’s sounds a small thing but it changed a way of life for many. I thought it was so sad. It’s another example of where a generation doesn’t understand the reasons for something happening and perhaps the importance of knowing those around you.

It’s very different for young people now. What is the fascination with Facebook? What’s the fascination of being on your phone twenty hours a day? What is it? You think a lot of young people are already fed up with it, they don’t want to be on demand. They don’t want their parents checking them out every five minutes any time they want to, or their friends sending inane messages that they feel they have to answer. It will be interesting to see how things change in the digital world of communication and the actual world of communicating with flesh and blood.

I used to have a screen dependency issue myself, but I tried to change that when my son was born, because I didn’t want to naturalise the idea he should spend most of the day looking at a screen, or to always be on call. It’s like that at the university where I teach. If a student emails and if I don’t write back in an hour they will send me another message asking why I haven’t responded. Now I’ll tell them that good asparagus takes four years to mature, so you can wait a little more time. And perhaps that’s what’s most interesting today, projects where people can find the space and time to slow down, to find some calm and perhaps themselves, much like you do in the Dial House garden.

Yes, that’s right. They just get on with. I don’t think it’s necessarily what scale but just get on with it. Some of them are big, like the project up in Todmorden. That’s a big project. That’s well known throughout the world now. It’s been going for seven or eight years I think? It’s a project where every tiny bit of land in that town is used to grow vegetables, and the community is invited to help themselves. That’s been an amazing project, because nobody has taken advantage of it. Each family take what they need and they help with maintenance. And it’s grown, and grown, and grown. I think that’s a lovely project, and people have been going to that place to see what’s happened and how it’s been done. I believe it was just a group of women thinking, “sod it, you know, this town could do better, food is expensive” – it’s a very beautiful town up in Yorkshire – but let’s see if we can take over bits of land and start growing food for everyone. They took over the land in front of the railway station that was just weeds. Took over a piece of land in front of the police station, which is full of vegetables now. People bring their green waste and they collect the resulting compost and take it back to their gardens. It’s lovely. They’ve now got a dairy in the town. They’ve got organic local meat, and they are now supporting the restaurants in the town. The local community has learnt when to pick the various crops and they only pick what they need. The whole project is lovely. Fantastic. It’s called Incredible Edible and has taken inspiration from the towns history to create what it has today.

There’s a lot of projects up and down this country where people have just said “we’re going to do it ourselves.” Council estates where it’s just been junk cars and everything has been spoilt and where they’ve asked the council to clear the space, but who don’t do anything because they have no money and no interest, so in the end they’ve done it themselves. They’ve planted an orchard. The community has got involved. The children can now grow vegetables and realise peas are not only in tins. The change that has happened in those communities is amazing. Eve Libertine is part of a group in London that has made a project for the local community. Just down the end of the street she lives in there’s was a small park, but to get into the park you had to go through needle alley. It was just crap and dangerous, especially at night. They finally got access to that tiny piece of land and they’ve created a community orchard. It’s small, but it’s got ten beautiful fruit trees that are now mature. They have started a tradition of holding an apple festival every year. It’s much safer to go into the park this way now and local people have formed new friendships.

They are tiny things. They don’t make the news, but it makes a profound effect on the area you live in. That’s where my interest lies, in undermining the accepted state of things. I’d like to undermine the whole system in some way, because the system is forever trying to keep us apart. Keeping you apart stops you sharing your energies and ideas. I love projects to do with the land, because I think children especially, feel part of something. Young people have a chance to feel they belong, and they don’t have to kill the pain by jacking up or all the rest of it, consequently it follows that they may grow older feeling at peace, confident and fulfilled with life. They may even end up asking themselves “Why do I want to go and look for a job?” I always encourage people to create their own way of making money. Why don’t you create something yourself? If you can’t do it on your own, find somebody you trust, or you love, or you enjoy, who has the same interest, and start a business. It’s not that difficult. If you want to make a million, yes, it’s very difficult. If you want enough just to live with, and be happy, it’s not so difficult. I think it’s easier, especially now with the computer around, there’s online marketing, online websites where you can sell from. It’s not difficult. If I can do it with Exitstencil Press, anyone can do it and I’m not that bright at marketing. I’m a terrible business woman anyway and end up giving half the stuff away, but I’m happy with what we’ve got, it ticks over. No, I think life can be very exciting if you choose to have a go and not take the regular route, certainly a challenge and you’ll find hidden depths of strength and capabilities you never knew you had.

Gee Vaucher, Introspective, at Firstsite in Colchester, is on from 12 November to 19 February