Tino Sehgal has a curious thing about curtains. Reading through old interviews with the British-born, German-raised artist, he speaks often of his estrangement from objects. He shops little and rarely. The only object I have ever found him admit to buying is a set of curtains. But this singular purchase he has spoke of several times, at different times, in different contexts.

His works, similarly, are bereft of material things – with, again, one single exception: a choreography for the curtains of Manchester’s opera house, created as an overture to an evening of works by different artists gathered under the title Il Tempo del Postino commissioned by Manchester International Festival in 2007.

This year Sehgal becomes only the second artist ever to be handed Carte Blanche over the entire 13,000 square metres of Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, France’s largest museum dedicated to temporary exhibitions of contemporary art. What is most startling about this show is its bareness. It is almost shocking to walk through these cavernous white halls and find them bare of paintings, sculptures, or physical installations of almost any sort. Except, that is, for another pair of curtains.

Upon entering the Palais from the avenue du Président-Wilson, visitors pass through a cascade of beaded curtains, an untitled work by Félix González-Torres from the early 90s. Emerging on the other side of this theatrical device, they will be met by one of Sehgal’s participants and asked, “What is the riddle?”

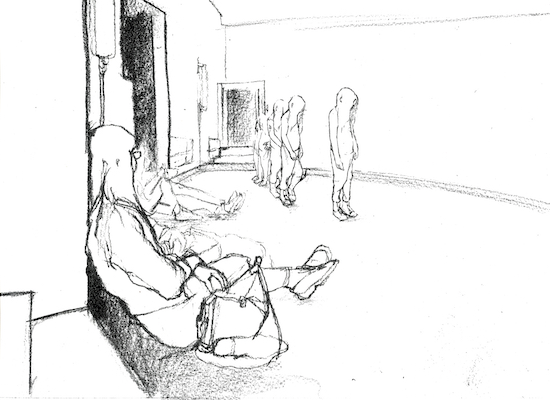

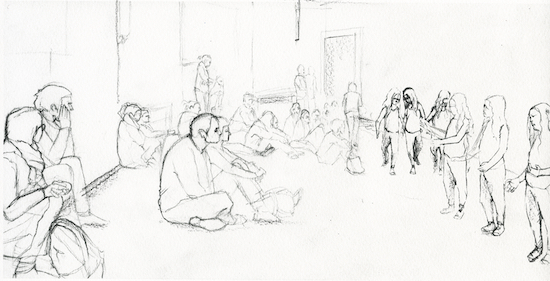

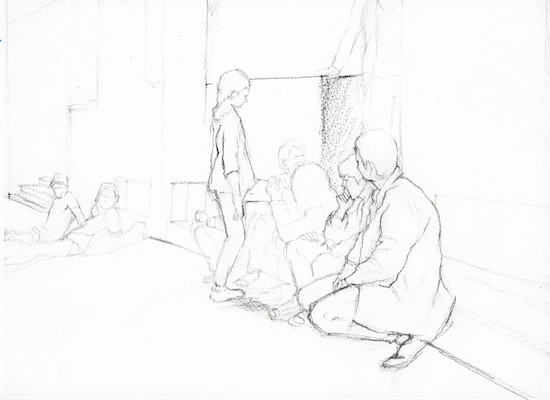

People, and the questions they ask, the stories they tell, and the movements they make, are the substance of Tino Sehgal’s work. His participants are the works’ only physical presence, the only thing to disturb the otherwise ghostly silence of these exhibition halls. Over the course of the several hours I spent wandering about the Palais, I was alternately guided and abandoned, interrogated and narrated to, coaxed and cajoled by people from age ten to eighty-two, few of them professional performers, all of them improvising semi-autonomously under the loose instruction and intensive training of the artist himself.

Sehgal calls them “constructed situations”, taking the phrase from the Situationists. Specifically, from a text by Guy Debord entitled ‘Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action’. “Our central idea,” wrote Debord in this pamphlet of 1957, “is the construction of situations, that is to say, the concrete construction of momentary ambiences of life and their transformation into a superior passional quality.” He speaks of a “revolution in mores,” of expanding “the nonmediocre part of life,” of “taking a stand in favour of what will bring about the future reign of freedom and play.”

So are these works programmes for a new society? I ask.

“I wouldn’t have this kind of programmatic, dogmatic – and also I think a little bit delusional – ambition that [the Situationists] had,” Sehgal demurs. “But, on the other hand, I’m very interested. The creation of new passions! That’s very interesting, I think. Is it possible to do it? I don’t know. Does my work do it? I don’t know. But it’s a thing that I’m curious about.”

We’re sitting, a little awkwardly, side-by-side, on a sort of sprawling ottoman couch, somewhere near the cloakroom, on the ground floor of the Palais. “If you and me right now,” he says at one point, “instead of sitting on this weird pillow, we were sitting in a fancy restaurant opposite each other, it would be a very different experience – although, we would be maybe saying the same thing. I think for humans, just being in a setting somehow, is very different.” There’s a sort of odd pause between the word “set” and its “–ing” here, as if he only decided at the last minute to say the general “setting” instead of the more implicitly theatrical “set”. I’m reminded, again, of his curtains.

The experience of interviewing Tino Sehgal is a little bit like slipping into one of his works. I found myself led, by the exhibition’s PR, into a back room and cursorily introduced to a woman called Rebecca who sat down with me and immediately began talking about “organic movements”, “energy flows”, and “fluxes”. Only half way through this spiel – since nobody had told me – did I realise I was talking to the show’s curator, Rebecca Lamarche-Vardel. Like a sequence from Sehgal’s work This Progress, first performed at the New York Guggenheim in 2010 and revived here in Paris six years later for this exhibition, she then passed me smoothly onto Sehgal himself to continue the conversation.

Upon meeting him, I was still rather flustered from just coming out of the works themselves, the experience of which I had found little short of traumatic. It had been a succession of bizarre encounters in which I was repeatedly addressed and looked in the eye but never once felt like any of my interlocutors really wanted to engage with me. They would deliver their sometimes jarringly frank prepared patter and depart, like that, without so much as a farewell and pleased to meet you. One young woman opened our dialogue with the alarming insistence that “handwriting is an erotic activity.” I soon longed for the minutiae of real interaction, the delicate manoeuvring and subtle negotiations of small talk which so amiably clear a space for genuine reciprocity.

It’s not just your use of the phrase, ‘constructed situation’, I start to venture, but also because you’re dealing with people. You’re immediately confronted with what kind of looks like a society of people –

“Yeah, yeah,” he nods thoughtfully.

And so, one immediately starts to think, what are the relations between this society – or even what are the relations between you and this society?

“Yeah, yeah…”

Are you the dictator of this society, or…?

“I’m like the lawmaker, maybe,” he says. “Not the dictator because I have no idea what they say.”

Of course! I laugh. I mean, after all, there’s no KGB here!

“Ha!” he starts before continuing enigmatically, “maybe… Maybe, actually – the people who manage the works, they’re giving me some feedback…”

I hadn’t considered them before, but I could see them now. The men and women standing by in many of the rooms below, not quite participating but not simply spectating either. The artist’s own secret police, keeping an eye on his subjects. Supervisors on the shop floor, carefully managing the affective labour of each employee.

In Carl Neville’s novel, Resolution Way, published earlier this year by Repeater Books, employees at the quasi-Morleys fried chicken shop that Neville dubs Heart of Chicken are forced to wear a device called an ‘affective monitor’. It keeps tabs on the workers’ vital signs, ensuring the smile they show to customers is truly sincere – or face the sack.

I thought of Neville’s satire sometimes while wandering through the Palais de Tokyo. Were Tino Sehgal’s works an indictment of the forced affective labour that characterises twenty-first century workplaces like Starbucks or merely another example of it? Was I supposed to feel this alienated, this disturbed by each hollow-eyed simulacrum of a genuinely meaningful human encounter? Talking to Sehgal himself I could gather few clues.

When a sculptor manipulates clay, I start to say, or when a painter manipulates paint, you don’t really need to worry about how the clay or the paint feels about –

“I hear what you’re saying,” he cuts me off sharply, “but how does that argument apply to a theatre director or a film director? Same thing. No?”

I’m not sure. Somehow it doesn’t feel the same…

“Each of the works is making something different resonating in you,” Rebecca Lamarche-Vardel had said to me earlier. “It is very much about the plurality or the diversity of the selves that you acquire when the works are going through you. That’s the idea of Tino’s work. You don’t look at a work anymore, you have to experience it. You have to be part of that flux for it to exist. The beauty of this is that the exhibition is never finished. What we see now will no longer exist tomorrow.” All that is solid melts into air.

Tino Sehgal’s Carte Blanche at the Palais de Tokyo continues until the 18th of December