Sisters photographs either by Les Mills or unknown

‘Alice’ – the song that more than any other changed Andrew Eldritch’s life – was written in ten minutes while sitting on a sofa.

Eldritch recalls that he “didn’t sit down to write an attitude-adjusting single with more ambition [than previous songs] but the success of ‘Alice’ made me have a re-think. Things were different after that.”

‘Alice’ transformed him from Andy Taylor – an “unprepossessing youth”, unemployed, and a college drop-out twice over – into the mesmerising, near mythical Andrew Eldritch.

Before ‘Alice’, Andy Taylor was just one of many habitués of a grimy Leeds punk club who had a band on the side. “Eldritch” was just a name Taylor used when he made records and played gigs, neither of which he did that often.

‘Alice’ began a sequence of stunning EPs and live shows that made Eldritch the most compelling British rock & roll performer of his generation. And this is the story of how on earth that happened.

Taylor was born in Ely; Eldritch was born in Leeds. This is also the story of where on earth that happened.

History has been kinder to other vibrant post-punk centres – Manchester, Glasgow, Coventry, Sheffield or London – than it has been to Leeds. Yet, to know these Sisters – no hats, no dry ice, pre-Warners, pre-Hussey – one must also know Leeds. Red Leeds, post-punk Leeds, post-industrial Leeds, post-Yorkshire Ripper Leeds, post-Division One Leeds; Leeds before it became Gotham City.

Andy Taylor – a 19-year-old Deep Purple fan, with “shoulder blade length red hair” and “one pair of shoes, this old pair of trainers I’d been wearing since I was fifteen” – arrived in Leeds to study Chinese at the University in October 1978. It was his first time in the city. His knowledge of the north of England had been limited to episodes of Coronation Street. “I discovered it was a documentary,” he says.

He had parted company with St John’s College, Oxford so late in the previous academic year that the University of Leeds had very little student accommodation left. Taylor was lodged way out of town near Leeds United’s Elland Road ground “in a housing estate of utter grimness, which has since been declared uninhabitable and knocked down.”

Yet, Taylor liked Leeds instantly. That The Ramones were playing The University the week he arrived, no doubt eased his transition. “I must have gathered from that, from fliers or talking to people that there was this F Club.”

If there is one place in Leeds that can claim to be the birthplace of Andrew Eldritch it was “this cellar dive.”

The F Club was the Leeds equivalent of Eric’s in Liverpool. It was in the basement of Brannigan’s nightclub down the bottom end of town near The Dark Arches, a complex of vaults under Leeds railway station.

The F Club was run by the great Leeds promoter, John Keenan. “I used to do at least two nights a week down there,” he recalls. “The manager of Brannigan’s was very forward thinking: two discos on top, punk club below.”

Danny Horigan who roadied for The Sisters (and would later sing in Salvation under the name Danny Mass) remembers The F Club thus: “At the bottom of the stairs, there was a pool room and then you went round the corner to where the bands were on – stage at one end, DJ at the side of the room. Really low ceiling, proper dirty, sweaty punk club.”

A decade later The Duchess of York pub in Leeds became legendary because Keenan put on Nirvana, Oasis, Pulp, Coldplay and Radiohead before they were massive, but for Keenan, “The F Club at Brannigan’s had the more important bands.”

Pere Ubu with The Human League supporting sticks in Keenan’s mind. Eldritch’s too: “That’s my favourite gig ever. I’m still haunted by the dual genius of it. I just can’t think of that happening anywhere else, at least not with the same intensity.

“The big bands played the Uni so we’d trot up there from time to time but it definitely wasn’t home, whereas The F Club had all the new stuff, all the time. I practically lived in The F Club.”

As well as the draw of the bands, there was the lure of the DJ, Claire Shearsby. The unprepossessing youth found himself “going out with the glamorous DJ and we lived together for years.”

Shearsby and Taylor were sketched by The Mekons:

"In the flat above the chemists

Andy and Claire are dressing to kill

But they don’t come out till after dark

In Charlie Cake Park."

“He’d be down at every gig with Claire,” recalls Keenan. “When Claire was DJing and wanted to go to the bar or to toilet or whatever, Andy would take over for a bit and all he ever played was Iggy Pop, David Bowie and Gary Glitter.”

“You could always tell when I’d taken over,” Eldritch confirms “because on came the Glitter.”

October 1978 – the month Andy Taylor came to Leeds – was when the F Club had moved to Brannigan’s

Keenan had first begun putting bands on at the height of punk in the summer of 1977 in the Common Room of Leeds Polytechnic. He billed these nights as ‘Stars of Today’. The music was “basically punk – The Slits, Slaughter & The Dogs, XTC,” he says. “When the students came back after the holiday, the new Common Room Committee wouldn’t let me have the regular weekly club. So basically I said ‘Fuck the Poly’”.

This was the “F” in F-Club.

“It was such a good group,” remembers Keenan. “All the intelligent kids – not necessarily university kids; there were kids from the estates – who realised change was in the air and had attached themselves to the club.”

“When I moved from the Poly I thought ‘How am I going to keep them together?’“ Keenan’s answer was “to form a club and give them a club card that cost a quid and would get them reductions at some of the punk shops in Leeds, like X Clothes.”

The F Club’s first home was The Ace of Clubs – a decaying cabaret joint – where it only ran from September to December 1977. “I put a fair selection on – Wilko, Siouxsie,” remembers Keenan, “but there was a fire and the insurance wouldn’t pay out.”

After the Ace of Clubs, Keenan moved The F Club to The Roots Club, a primarily West Indian venue in the Chapeltown area of Leeds. This was a former synagogue that had gone under various names: The International Club, The Cosmopolitan Club, The Glass Bucket. As the venue of The F Club it hosted, among others, Suicide, Joy Division, Magazine, Wayne County and The Electric Chairs and Wire.

Claire Shearsby DJ’ed at all the locations of the F-Club, even at the ‘Stars of Today’ nights at the Poly. “She was there at the birth of it,” states Eldritch. “Absolutely. People don’t give her enough credit. A lot DJs would have baulked at playing the stuff she did. She was like the John Peel of Leeds.”

Brannigan’s was the longest lasting of The F Club’s locations. It was there that the three young men who would become The Sisters of Mercy met. Craig Adams from Otley, a market town about 10 miles outside Leeds; Mark Pearman from Hull; and Andy Taylor were some of “the bright kids with some style about them”, in Keenan’s words, who were drawn to The F Club, in Adams’ case, illegally so, since he was underage.

In the Leeds post punk music scene, “there was a very definite divide between art school uni types and the townies”, recalls Eldritch. “The F Club was very much a townie affair. I was much more townie than student and my academic record proves it; I fell in with the dirty crowd.”

The ur-F Club townie band were The Expelaires. “The Expelaires were like the house band,” remembers Eldritch. “They had their tendrils in pretty much everything,”

Bass player Mark Copson went on to sing in Music For Pleasure; guitarist David Wolfenden joined Red Lorry Yellow Lorry; Carl “Tich” Harper became the drummer with Girls At Our Best; and the singer Paul “Grape” Gregory formed 3000 Revs with future Sister, Adam Pearson. Craig Adams the rhythm guitarist-cum-keyboard player went on to form a Soft Cell-ist electro pop duo called Exchange before becoming the bass player in The Sisters.

In the art school camp were Gang Of Four, The Delta Five and The Mekons.

Jon Langford, the drummer in The Mekons agrees that, “the distinction was quite pronounced at first; there was a class/geographical element to it. The Mekons and Gang of Four were mostly public school boys from the south of England. Me and Dave Allen (from Gang Of Four) and Ros (from The Delta 5) were more regional and hickish.” To complicate this matrix, Jon King, Gang Of Four’s singer was both working class and a public school boy.

“The F Club was a wonderfully accepting and inclusive place, except for Nazis,” Eldritch recalls. His own trajectory from private school to Oxford and his accent – close to Bowie’s well-spoken Bromley – mattered little to the working class West Yorkshire locals of The F Club. The long red haired Southerner was made more than welcome.

Although Taylor had oriented himself away from the University, he was still acquainted with the Gang of Four, but not within their inner circle. He was impressed by them then – not least because they were unemployed and in a band – and he remains so, nearly 40 years later: “They had these amazing songs and they played so well. They were hard and bouncy. They had everything but they couldn’t fully commit to the glorious stupidity which is being in a rock & roll band.”

Taylor – as Eldritch – could and it made him a star.

Taylor’s path crossed with the other ‘art school’ bands more.

“Claire and I used to hang out with Ros from The Delta 5 because she lived a few doors away from us,” remembers Eldritch. “She was – probably still is – a lovely, lovely person.”

“The Mekons were fun to hang out with too,” he adds. “They were doing stuff like ‘Teeth’ at the time, which is very good indeed. We used to get on very well with Kevin Lycett and Jon Langford.” Langford recalls that he “used to go round to Claire and Andy’s flat and watch old Doctor Who episodes on a tiny black & white TV.”

Eldritch pays particular tribute to Lycett: “I owe a lot to him. He encouraged me in my quest to learn a little bit about being in a band and scrimp and save for visits to the studio and keep hammering away at it. By the time he stopped being that kind of mentor, we still had nothing to show for it, but his encouragement never wavered.”

One version of The Sisters of Mercy story casts Andy Taylor – or rather his alter ego, Andrew Eldritch – as a Machiavelli with a masterplan for rock stardom, pulling the strings from his lair in west Leeds.

It isn’t Eldritch’s version. At least not before ‘Alice’ came out.

In their first year and a half of existence, The Sisters of Mercy made one awful record, rarely played gigs and didn’t have a stable line-up.

Eldritch explains it thus: “We were taking a lot of medication, going down The F Club – gigs weren’t going to watch themselves – and we hadn’t got any money.” The Sisters “were too busy hanging out” to be effectively charting a course to rock stardom.

One regular haunt was The Faversham Hotel “which happened to have a very late night bar, so that could be quite useful,” Eldritch explains. “He was in The Fav quite a lot playing pool with Claire,” recalls Danny Horigan. “Claire was really good and people thought because she was blonde and looked like Debbie Harry they could beat her.” Challengers were regularly disabused of that notion. “The fact that she could do that on a serious amount of medication was quite impressive,” remembers Eldritch fondly.

There were also videos to be watched. The VCR was a big deal at Taylor and Shearsby’s. There weren’t that many tapes but they were watched repeatedly. Visitors recall AC/DC, Doors documentaries, Motorhead and Apocalypse Now! being on the playlist.

Eldritch believes that the instability of early Sisters’ line-ups was inevitable due to the “fluid nature of relationships around The F Club. Everybody slept with everybody else; the line-ups of every band changed absolutely regularly. Everybody else who had a bit more nous musically (than me) would move from one band to another.”

Dave Thompson in Twenty-Five Years In The Reptile House correctly describes The Sisters as “floundering in slow motion and taking a long, and not especially scenic route to the stars.” The version of this band that made ‘Alice’ – only their third single – was effectively The Sisters of Mercy Mk III. That line-up was not established until March 1982.

Over two years earlier, Jon Langford had sold Taylor The Mekons’ legendary fish tank drum kit. Langford recalls that “it was my second ever drum kit that Corrigan from the Mekons and I lovingly covered with Woolworth’s bathroom fish tank vinyl. We took all the fittings off and did a really amazing job. Andy painted it black. He painted it black, maaaan!”

Whether Taylor did much more then redecorate his instrument is not clear, he certainly didn’t form a functioning band with it. Paul ‘Grape’ Gregory has a tentative memory of a proto-Sisters that “originally had my friend Keith Fuller as the singer. I was round Claire and Andy’s place off Belle Vue Road and Keith was on the mic.” Pearman was on guitar and Shearsby seems to have played keyboards.

The first iteration of The Sisters proper was the rump left after failed rehearsals: a duo of Taylor and Pearman. Taylor played the drums and sang. Pearman played the guitar and sang. They were both poor.

“I ended up with Mark because we were basically the last two kids to be picked for the team in the playground,” recalls Eldritch. Pearman had actually been in a band before (called Naked Voices) and had played a few gigs, which would have made Taylor the shortest of the two short straws.

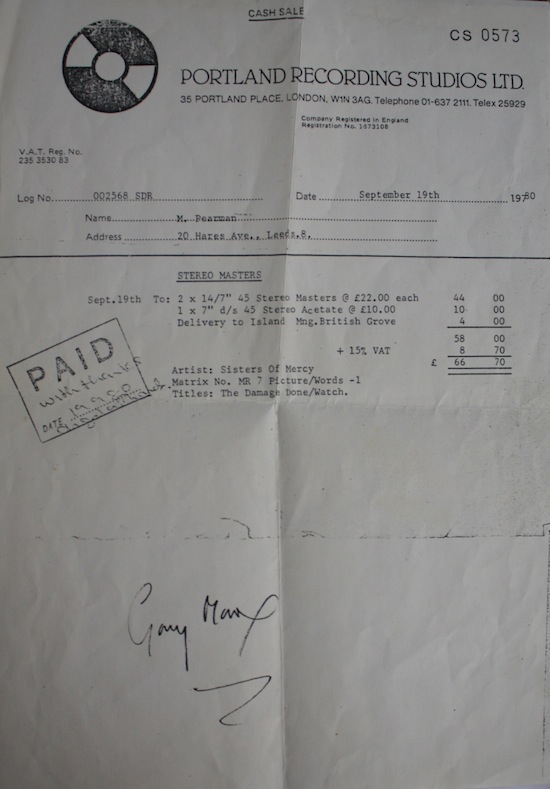

Acetate for ‘Damage Done’ single, thanks to Phil Verne

‘Damage Done’ invoice, thanks to Phil Verne

They never played live but did make a single, ‘Damage Done’. An account of this shambles was written by Eldritch (we assume it was he, despite the third person) for the The Sisters’ official website. “So it came to pass that our intrepid sonic explorers booked themselves half a day’s studio time at RicRac Studios, which was (and possibly still is) a shed in Wortley. Wortley is a run-down industrial area south of Leeds … The studio owner was, naturally, the only one who knew how to operate the studio, so he did the engineering. With a beard. Our heroes found it difficult to convey to him what a non-cabaret act might sound like. As a result, nobody knew what they were supposed to be doing. The engineer lost himself in a place where no engineer had gone before (or since), somewhere near the worst of both worlds.”

Despite the evidence on ‘Damage Done’, other Yorkshire bands were not put off recording at Ric-Rac. They included Skeletal Family and The Danse Society. And The Grumbleweeds.

Despite the debacle in Wortley, Pearman and Taylor were back at it a few months later, this time in front of an audience. “Our sonic explorers” now had a drum machine and an actual musician in the line-up. More than that, the musician in question had made records infinitely better than ‘Damage Done’, had played gigs supporting The Teardrop Explodes and The Bunnymen and had and had even recorded a Peel Session. This was Craig Adams from The Expelaires.

This second iteration of The Sisters was therefore Taylor as the lone singer, Pearman on guitar, Adams on bass and a Boss DR55 Dr Rhythm as the drums. The simplicity of the early drum machines coupled with Adams’ love of Hawkwind at their heaviest, gave The Sisters genuine attack and a primitive, brutal groove, if nothing else. Whatever – and whoever – else might malfunction, the bass player was rock solid.

Taylor also shared Adams’ taste for Space Ritual: “We wanted to be The Stooges. We wanted to be Suicide. We also wanted to be Hawkwind. Their ‘… and the wizard blew his horn’ stuff is patently nonsense and rubbish and sullies their reputation, but their psychedelic space rock is outstanding.”

The trio’s first gig was a CND benefit on Monday February 16 1981 in Alcuin College in the University of York. They were support for the Thompson Twins, well before The Thompson Twins trimmed town to a trio and had pop hits.

Eldritch – in website third person and vivid present – recounted the first show at Alcuin College show thus: “Marx has connected his guitar to a record-player pre-amp which feeds back uncontrollably and Eldritch has shifted the vocal echo into overdrive. It’s metal dub without any spaces, on a shuddering mechanoid backdrop.”

It is entirely possibly that this is more fun to read than it was to listen to.

The Sisters of Mercy’s second gig – on Thursday 19 March 1981 – was their Leeds debut. They were support for Altered Images. Fittingly, it was in The F Club at Brannigan’s. Keenan’s first impressions were that “they didn’t have the drum beat right … and Andy was trying to sound like Bowie doing ‘"Heroes"’.” Taylor was immediately making excuses for it in the Leeds fanzine Whippings and Apologies: “That was a real balls-up because of the bad sound … A lot of the stuff we do depends on us having a good PA. Without a decent PA, we sound really crap.”

“It was basically kids learning to play on stage,” comments Keenan. The Sisters of Mercy did get better but progress was slow, not least because they played live so rarely. Taylor claimed to Whippings & Apologies, that this was tactical. “We don’t see the need to play in every toilet every week because there’s no percentage in it. We could play The Pack Horse or The Royal Park every week but it wouldn’t be worth it. It’s not that we think we’re better than those places, it’s just that we know we’d sound shit in them.”

At The F Club Keenan “had a night called ‘The Sheepdog Trials’ – four bands on at a time to give them a chance. Some of them were really bad, some were really good,” he recalls. “I’d use the better ones as support to decent bands. The Sisters didn’t go in ‘The Sheepdog Trials’. Because I knew Andy, they went straight to supporting.”

Even The Expelaires went in The Sheepdog Trials. Whatever misgivings Keenan had about The Sisters’ F Club debut, he liked Taylor and sensed potential. He had “long, greasy black hair, glasses – skinny – but Andy had something about him. He was never one of the lads; he was always in his own little space. He was not a follower. You did notice him; he was not like everybody else.”

The second time Keenan put The Sisters on in Leeds was on Sunday 22 March 1981, three days after their Brannigan’s show. This was an all day fundraiser for The International Year of the Disabled Person that featured 12 bands and 5 poets. The Sisters were third from bottom of the bill.

This took place in in Tiffany’s, a huge, mainstream, city centre nightclub. At the weekends it attracted the same sort of clientele as Heaven & Hell or Cinderella Rockerfella’s in Leeds, the latter owned by Peter Stringfellow. “Tiffany’s was the second biggest venue in Leeds after the Queen’s Hall. It was owned by Mecca and held 2,500 people,“ remembers Keenan. “I had a deal with Tiffany’s for the off nights, when they were not having a disco.” He put his bigger bands on there: Bauhaus, Squeeze, The Stranglers, U2 with The Comsat Angels supporting.

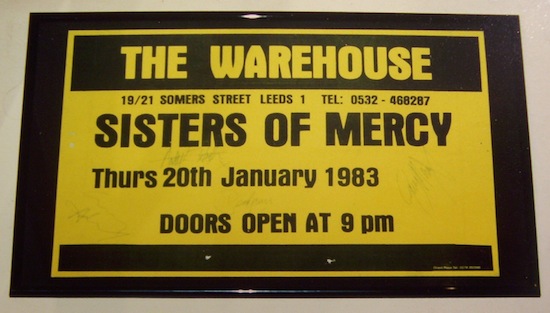

Keenan also put The Sisters on at The Warehouse. The Warehouse was a short walk, but a world away from Tiffany’s. It was the Leeds version of New York’s Danceteria ie. The Hacienda of Leeds. Unlike Tiffany’s, The Warehouse’s main clientele were those of an alternative persuasion – New Romantics, post punks and devotees of electronic music.

Mark Musolf, Leeds born and bred, (also now also known as DJ Mark M) recalls that “with Brannigans it was more of a hard edged punk ethos. With The Warehouse, the bands there had a different appeal. Soft Cell were practically the house band there for a while. Marc Almond’s old on stage party piece was to smear himself in cat food.”

The Warehouse was owned by Mike Wiand, an American who “was a spy basically,” according to Keenan. “He worked at Menwith Hill listening station. When Mike died in 2014, they gave him a military funeral.” Wiand “wanted it be cutting edge,” says Horigan, “so he loved the weirdos. Even the pop and soul nights were a bit different.”

Eldritch is ambivalent about The Warehouse. “In all of my days as a card carrying member of The F Club, I don’t think I went to The Warehouse more than three or four times,” he states. “The drinks were more expensive and the carpet wasn’t sticky. I didn’t take me very long to get banned from The Warehouse. Officially I’m still banned from there. For damaging a glass when somebody pushed it into my face.”

Keenan put The Sisters on late at The Warehouse on July 2 1981. This show gave them a massive boost in the Leeds scene. Iggy Pop played the University and Music For Pleasure were at the Amnesia club that evening. Parts of these crowds converged on The Warehouse for The Sisters looking to prolong their night out. “All this heat and energy was in this one small club”, remembers Paul Gregory. The Sisters impressed him and many others. They were “kind of chaotic but there was a noise there.”

Keenan had tempted Iggy to The Warehouse with the promise of The Sisters’ version of ‘1969’. After much dancing in the upstairs bar, Iggy ended his night pinned to a wall in The Warehouse by the bar manager because he’d ripped down a poster for what he termed “a New Ro-fucking-mantic night,” according to Keenan.

The Sisters and Iggy did not meet.

Photograph of Sisters’ Leeds Warehouse poster, thanks to Phil Verne

Claire Shearsby also DJ’ed at The Warehouse as did Marc Almond. “Marc’s DJ slot used to last about 30 minutes in the middle of the night,” recalls Mark Musolf. “As more and more New Romantic, post punk and alternative types went to the Warehouse, the slot widened. Once ‘Tainted Love’ charted, Marc left.”

When Taylor saw The Ramones play in in early October 1978 it was in The Refectory of Leeds University’s Students Union.

“The Refec” had legendary status as the location of the recording of The Who’s Live At Leeds. Any major rock act that toured in the 70s had played there: Floyd, Led Zep, Roxy, The Dolls, The Stones, Sabbath, Wings, Mott.

Yet, the university played only a minor role in the life of The Sisters. There were two reasons for this. Taylor ceased to be a member of the university in order to avoid his compulsory year out in post-Mao China which would have included a sub-zero Beijing winter and Andy Kershaw, the Leeds Union Entertainments Secretary (“Ents Sec”) “fucking hated us and it was mutual,” states Eldritch.

Kershaw, who would later find fame as a Radio One DJ, booked bands from March 1980 till mid-1982 into The Refectory, the main hall. The Sisters got on bills in The Riley Smith Hall, a smaller venue in the Union, or in The Tartan Bar, an even smaller venue at the rear, but Kershaw had no intention of giving The Sisters a support slot in his beloved Refectory.

When The Sisters did finally play The Refec it was as headliners in May 1984.

In their first year, when The Sisters did occasionally play, it was almost entirely in Yorkshire – in Leeds seven times, York twice and once at Caesar’s in Bradford, opening for Nico. Like several early gigs, whether this actually took place is disputed. It is omitted from the official gigography, although a flyer is extant.

Their only gig outside the county was low down the running order on the Saturday of Keenan’s Futurama III festival in the Bingley Hall in Stafford, the third edition of his “World’s First Science Fiction Music Festival”. They were added so late that they did not appear in the line-up in most of the advertising. The Sisters went on at 3.30 on the Saturday afternoon, Taylor announcing the beginning of their set by shouting “bring out your dead” to the sparse crowd milling around what resembled a very large cattle shed. The Bingley Hall was the main pavilion of the Staffordshire County Showground; during Futurama 3 it still smelled of livestock. Nine hours after The Sisters, Gang of Four headlined.

In total, Keenan booked The Sisters six times. There would have been a seventh in Leeds in December 1981 but it was cancelled due to heavy snow.

“I created the swamp they could crawl out of,” he says proudly. “And what a fine, fetid swamp it was too,” agrees Eldritch. “We couldn’t have got anywhere without the support he gave us.”

The Sisters Mk II spent their first year of intermittent gigs having great difficulty finding a 2nd guitar player. “I don’t know why but a lot of my riffs seem to beg for somebody doing what we call ‘the chugs,’” says Eldritch. Dave Humphrey played in The Sisters sometimes, including the Bingley Hall show and Tom Ashton, soon to be of The March Violets, filled in on two occasions. Any momentum they had from The Warehouse and Futurama gigs dribbled away through the Autumn and Winter of 1981. Finally, by February 1982, The Sisters had found an excellent solution to the troublesome fourth slot in the band: Ben Matthews. He remained a member until September ’83.

Yet one year into their time as a live proposition, The Sisters Mark III – the iteration that made ‘Alice’ – was still not quite ready. When Adam Sweeting of Melody Maker reviewed their gig at the University of York on February 5 1982 – The Sisters’ first national press – Craig Adams wasn’t there. Jon Langford was playing bass while Adams was in The Canary Islands working as a photographer’s assistant.

The Sisters had, most definitely, improved though. “I remember the stage being full of smoke,” says Langford. “No amps just pedals and a drum machine, guitars straight through fuzz boxes straight into the PA system. Visually amazing. I was amazed how packed it was. The kids went mad mad mad mad!”

In February 1982, The Sisters were also in an 8 track recording studio in Bridlington, a seaside resort in east Yorkshire, to record ‘Adrenochrome’ and a newer song, ‘Body Electric.’ This was a not a repeat of the Ric-Rac debacle, but there were technical issues.

Langford: “We were mixing at Ken Giles’ studio in a garage. I remember EQ-ing a bass drum all day, which we pumped at maximum volume through a huge PA that was crammed in Ken’s tiny studio. Hours of thump thump thump rocking the whole seafront. But when we listened back to what we had on tape it always sounded like a mouse tap dancing.”

Nevertheless, The Sisters had struck gold with Ken Giles’ studio. Mk III’s great run of singles and EPs that began with ‘Alice” were all recorded with Giles in Bridlington.

Between the recording and release of ‘Body Electric’ (on Langford’s own CNT label), Adams returned to Leeds, thereby properly inaugurating The Sisters Mk III.

Eldritch, Marx, Adams, Gunn.

This first classic line-up was heavy with pseudonyms. Matthews’ reference to ‘Treasure Island’ – “Ben Gunn” – lacked the outright hilarity of Pearman’s mash-up of Socialism and Glam Rock – “Gary Marx.” Taylor’s choice was a Philip K Dick-referencing declaration of his own literary sensibility and speed consumption – “Andrew Eldritch.” Arguably the drummer had the best name of all: “Doktor Avalanche”, allegedly named after a Swiss football referee.

The Sisters Mk III’s first gig was March 29 1982 – a Monday night – in a first floor club called ‘Funhouse’ in the West Yorkshire town of Keighley. They were billed as a “Leeds cult band.” That Keighley is less than 20 miles from Leeds indicates how small a shadow The Sisters cast at this point. The next day they were back in Leeds playing on another of John Keenan’s bills at Tiffany’s.

Then, over the next six months, compared to the previous 18 months of their existence, The Sisters went into interstellar overdrive: ‘Single of the Week’ in Melody Maker, a choice slot opening up for The Birthday Party in London, a Peel Session broadcast in September and a short tour as The Psychedelic Furs’ support in October.

In this period – the prelude to their first Golden Age – Langford thought The Sisters “were slick. I was impressed by the minimalism and professionalism; I was a Mekon though, so it’s all relative.”

Other than a stable line-up, there were other signs that The Sisters were beginning to click. The chaff had been purged from the set and Eldritch had a real affinity for The Doktor. Hours and hours, it seems, were spent tinkering with and programming the latest drum machine and writing the code in a notebook. Langford recalls that “Andy became my drum machine guru. Every time he bought a machine and had it modified, I did the same thing.”

In the middle of this period, Eldritch wrote ‘Alice’.

That he had effectively altered the course of his life in ten minutes on a sofa in the flat above the chemist he shared with Claire Shearsby, was not yet apparent.

Vital to this transformation and to the creation of ‘Alice’ were The Psychedelic Furs.

Theirs was another F Club gig that has stayed with Eldritch. “I saw all 25 of them lined up across the stage, all of them in black, all of them wearing shades and just bringing the house down. I was such a fan. That first album is still one of my top three albums ever.” The following year when The Furs were touring Talk Talk Talk Adams and Eldritch went to see them at Huddersfield Polytechnic. This was on May 29 1981 – a pivotal date in the destiny of The Sisters.

“We hung around at the sound check and I gave a cassette tape of our demo to Duncan Kilburn, the saxophone player,” continues Eldritch. “Famous and halfway famous bands got cassettes handed to them all day long, as subsequently did I. I never listened to any of them; life’s too short.

“But Duncan, bless him, did listen to the cassette which was handed to him by a kid. He passed it on and was encouraging and that gave us a massive boost. I can’t thank him enough. None of this would have happened [without him].”

The most direct practical help of all came from John Ashton, the Furs’ guitarist. When he heard the Huddersfield cassette (he recalled for Sex WAX n Rock n Roll) he thought “this is interesting, like a rock band with a drum machine … lot of distortion, very tinny, very trebly, but very intense, a very, shall we say, amphetamine-fuelled production.”

Eldritch was then still a year away from writing ‘Alice’. By the time he had, Ashton was looking for a band to produce. The timing was perfect.

Eldritch believes Ashton’s demos for ‘Alice’ were key to the final quality of the single. Ashton recalls (via Facebook) that “the amps were in the basement and my recording equipment was set up in the kitchen” at Eldritch’s and Shearsby’s. Eldritch, on hearing the results, suggested to Ashton’s shock, that it needed more treble. “It was already cutting your head off,” he recalls. “5K, I think was his favourite frequency.”

Then, over two weekends at Kenny Giles’ studio in Bridlington, The Sisters recorded ‘Alice’ and ‘Floorshow’ (along with ‘Good Things’; and ‘1969’) with Ashton. By their early standards, the speed and efficiency of this was astonishing.

‘Alice’ also set the business model for all their subsequent independent releases: The Sisters hooked their own Merciful Release label up to the powerful distributor Red Rhino run by Tony K out of York. There was “a schism” between Red Rhino and CNT, according to Langford. Tony K “finally snatched the Sisters away to Rhino. In the end all the bands including The Sisters had to leave CNT to sell any records.”

The options of sharing The Furs’ manager – Les Mills – also arose. According to Dave Thompson’s ‘Beautiful Chaos’, his band bio of The Furs, Mills “had been recommended to The Sisters … by Howard Thompson.” This must have impressed Eldritch. Thompson was an A & R legend who had signed Motorhead and Suicide to Bronze and The Furs to CBS. In Taylor’s world this was a Holy Trinity, but no matter how much he adored The Furs, “we chose not to get in bed with their manager.”

By Autumn 1982, Mk III was also definitely in its stride as a live proposition. Their October 5 gig in The Riley Smith Hall supporting The Furs was one of a week of free gigs put on as part of Leeds University’s Freshers’ Week. The night before had been Mud and The Flying Pickets. The Sisters were watched by writer (and obvious Bauhaus enthusiast) Nikolas Vitus Lagartija. What struck him was that the audience for The Sisters “were not students but local teenagers who had got their tickets off enterprising freshers outside.”

What hooked Lagartija (who is now an amateur Sisters historian) and “the enthusiastic local following” would bemuse and repel others: The Sisters of Mercy of Adams Marx, Gunn, Eldritch and Doktor Avalanche were a thumping motorik rhythm section, two extremely loud guitars and a frontman who had some bloody nerve to be singing like that and dressed that like in October 1982. The Sisters, as Eldritch once noted “came out and said ‘We are a rock band’. Very loudly.” Or rather the singer did. The others were almost an in-built riposte to his schtick.

Marx stood out because he was by far the tallest and most manic performer in the band. The other three humans, other than operate instruments and equipment, chew gum or smoke, actually did very little. Gunn moved only a little bit more than the Doktor, Adams only slightly more than Gunn, and Eldritch was a series of rock star tableaux vivants, as staged and as stylised as a body builder’s routine, with its transitions from one pose to the next.

This was part of what Simon Reynolds in Rip It Up And Start Again refers to as “an ultra stylized approach that treated rock less as an evolving musical form than a gestural repertoire of mannerisms and imagery”.

Eldritch, even knowing Reynolds means this as damning criticism, doesn’t entirely deny it: “If that’s all it was I would agree with him. We’ve also written some damn fine songs and play them with energy and a degree of wit.” Eldritch, it is safe to assume, despite his academic record, knew his Brecht and the importance of gesture.

The allusiveness of the imagery deployed by Eldritch was witty and fun. His shades, for example, were Les Grey of Mud, as much as Street Hassle Lou Reed, probably Hunter Thompson most of all. The leather pants: Lizard King. The bullet belt; ‘Ace of Spades’-era Motorhead. The imagery also went into high culture. The sleeve of ‘Alice’ was an adaptation of a Matisse, ‘Blue Nude’. ‘Body Electric’s’ was Francis Bacon’s ‘Head VI’, one of his ‘Screaming Popes.’ ‘Floorshow’ quoted ‘The Fire Sermon’, Part III of ‘The Wasteland’ directly or tweaked Eliot’s verse. “There’s hyperlinks in all of it, “ states Eldritch. “If you can stick three words of T S Eliot into a line you’ve automatically involved and enveloped the whole of The Wasteland and that just enriches what you do. ‘Floorshow’ is a very brazen example.”

To offset any high seriousness, Taylor truly was not afraid of the ridiculous in rock; The Sisters were playful with the full array of its history. Eldritch admits there was a huge dose of Alvin Stardust in the early stage persona: black leather outfit and black gloves was very ‘My Coo Ca Choo.”

There were also practical reasons for the gloves. “I wore them because I used to bite my nails and stages in those days, particularly at The F Club, were only 6 inches high and the audience was literally nose-to-nose with you. I thought, ‘I can’t be showing them nails like these.’”

Beyond the utilitarian, the signature Eldritch look “ties together with every kid of that generation’s Alice Copper fetish. There are no breaks in the spectrum that also includes Motorhead and The Ramones.” And Elvis, Gene Vincent and Vince Taylor. “It was all part of the glorious tapestry of popular music to us.” The title of a Vince Taylor compilation – ‘Jet Black Leather Machine’ -would work just as well for a collection of Andy Taylor songs. Or at least a Sisters bootleg.

Eldritch also mined the broad seam of queerness that has always run through rock & roll and been embraced by straight male performers. Eldritch was tapping into the long line of preening leather boys in British rock. This attitude had been fostered down The F Club. ”It was a very tolerant and inclusive place,” recalls Eldritch “Everyone liked to have at least one item of gay wear on their person.” The long-haired redhead that arrived in Leeds in 1978 was a huge New York Dolls fan. At The F Club, “personally, I was the representative of camp. Cyrus (Bruton) was the New Romantic side of The F Club, whereas Rodney (Orpheus) was on the Industrial side. Just because you’re Wittgenstein, doesn’t mean you can’t be camp.”

Bruton formed Dance Chapter (who signed to 4AD) and Orpheus would later found The Cassandra Complex. “We were all listening to The Stooges and Suicide, We just took it to different places.”

Reynolds – by far the best writer to approach The Sisters – considers them a complete failure as a rock band, but his positioning of them in the 1978-84 post punk era is most welcome, since most discussion of The Sisters shifts their centre of gravity to their iterations ‘84 and after.

Eldritch fits comfortably within Reynolds’ large cast of highly idiosyncratic artists fully exploring their own aesthetic in the considerable freedom punk afforded them, largely unencumbered by commercial imperatives. Keenan likens Eldritch to one of the major figures in Reynolds’ book. “Andrew reminds me of Genesis P-Orridge: showmen, the power of suggestion, a bit of charisma, a bit of kidology.”

Keenan also has an even more radical suggestion as to a key post punk influence on the young Andy Taylor: Pete Burns.

”I think the pivotal moment for Andy was when I put The Cramps on with Nightmares In Wax,” suggests Keenan. “Previously the punks had been into Day-Glo colours, but Nightmares In Wax came on all in black with white chicken bone jewellery, pale make-up on their faces. They made an impact.”

Eldritch disagrees but offers up Bauhaus at The F Club instead. “For the whole set their only lighting was a strobe lamp that Peter Murphy cradled in front of himself while he stalked the stage. He’d flicker it on a guitarist, the drummer, on his own chin at times. That lighting show was utterly amazing. I didn’t take much away musically from Bauhaus but I’m still very fond of that Expressionist kind of lighting.”

Certainly Burns, Murphy and Eldritch, as true children of Bowie, understood that rock music was a prime arena to create alternate personae and alter egos. Only a fool would try to genuinely disentangle Eldritch from Taylor – “Frankenstein from the Monster” as he puts it. They have surely fused after all these years; Eldritch grew directly from Taylor in the first place. He’d been experimenting with his look for some time, remembers Keenan. “I think they called him Spiggy after the archetypal rock star in ‘Private Eye’ – Spiggy Topes – because he was always acting the rock star. Nobody ever dreamt …”, Keenan trails off. “But fair play to him, he really pulled it off and showed everybody.”

Spiggy continued as Taylor’s nickname long into The Sisters. It was also the name of his and Claire Shearsby’s cat.

The Taylor/Eldritch transformation, a combination of will and self-study, was as total as that by any member of Kiss; Andy Taylor by his own account looks very little like Andrew Eldritch.

With his taste for Glam and what he termed ‘Heavy Metal’, it is of course possible that Eldritch was fully aware of the masked mystique of Kiss and impressed by the loyalty of the fan-base, the tribalism, and how much this was related to extra-musical accoutrements, the uniform, the insignia. Even as far back as the poor first single, Taylor had designed a brilliant logo – The Head & Star. This was essentially “Dissection of the head, face and neck” from Gray’s Anatomy, super-imposed on a pentacle. Stark, white on black, like “Motorhead, England”, that was certainly its inspiration, it too looked great on T shirts.

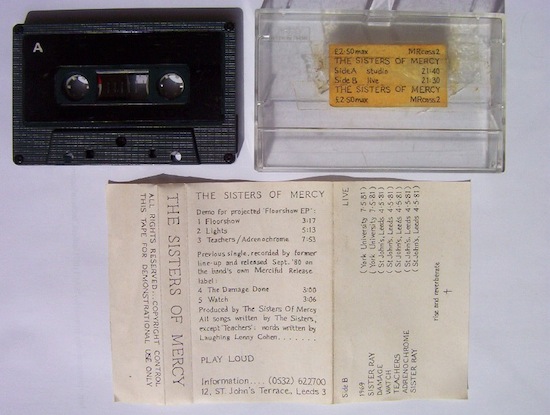

Floorshow EP demos and live recordings, courtesy of Phil Verne

By the late Autumn of 1982, on the cusp of the release of ‘Alice’, The Sisters, as Nik Lagartija had witnessed, already had the fanatical following of a metal band.

Or guerrilla leaders.

Eldritch had accidentally created his first revolutionary cell – the first “foca”, if we use Che Guevara’s term. Eldritch – pin-up, theoretician, agitator, conspirator – became the Che of the Leeds music scene. At his most narcissistic, magnetic, apocalyptic and egomaniacal, he would also become the Andreas Baader.

The Sisters and their audience found each other on club nights, via the radio and at gigs, via the music press, through fanzines and bootlegs. These punks may well have had broad tastes – Throbbing Gristle, B-52s, The Associates, whatever was in the Indie Charts – but fundamentally they were not looking for freaky futurism, synth experimentation or twisted funk. They wanted to dress up, they wanted to dance and they liked guitars and they liked drums. These lost (post) punks liked punk as a two word phrase – punk rock.

Wakefield (“Wakey”) – only 15 minutes from Leeds by train – has a claim to be the second accidental ‘foca’. Wakefield’s Sisters fans called themselves The God Squad and were the first hardcore following to mobilise outside Leeds. More would follow.

The punk and post punk scenes of Leeds and Wakefield had long been closely connected. Wakefield punks were regulars at The F Club gigs and those of Leeds were often over for the punk and Bowie night at Raffles nightclub on the Bullring in Wakey. Eldritch for his part went over for the Gary Glitter show Keenan put on at The Unity Hall in Wakefield.

In Leeds, The Sisters and their first fans would not have been strangers; they played in the same places they socialised. ‘Alice’ would begin to change that. Eldritch – neither garrulous nor extrovert by nature – completely understood the need to create distance between audience and performer, on stage and in the discourse he created around himself. In that space, a sophisticated play of projection and identification brewed between him and his audience. It created a profound and enduring mystique and adoration. Keenan, in true Yorkshire fashion, comments that “I still find it amusing he was idol worshipped. C’mon, it’s Andy Taylor!”

If there was one place that typified the demarcation between Eldritch and his audience, it was a basement club inside The Merrion Centre, that 1960s beast of a shopping centre that also housed Tiffany’s.

This dive – loved by many, but not by Eldritch – was Le Phonographique. “I was not a citizen of The Phono,” he states. He even takes issue the pronunciation – ‘faux-know’: “I know it shouldn’t be but it is.”

In quasi-Charlie’s Angels font, “Le Phonographique” promised “Vin. Bière. Cuisine. Discotheque.” All were sort of true. There was food and alcohol for sale and there was dancing – on a tiny dance-floor with a mirrored pillar in the middle of it. There were also famously foul toilets, usually in some state of inundation, and glutinous carpet. In late 1982, Alice’ became a fixture on the playlist of the DJ’s at The Phono. “I remember some spectacular dancing going on to ‘Alice’,” recalled the novelist David Peace in Dave Haslam’s Life After Dark, “all towering hair and flapping coats.”

Lagartija remembers The Phono in Autumn 1982 “as the main option for those seeking a club playing alternative music, with free admission and cheap drinks for students on a Monday night … it seemed to attract a motley crew who had come for the music and the vibe, with a barely changing set list, featuring Bowie’s ‘Queen Bitch’, the Velvets’ ‘Venus in Furs’, Killing Joke’s ‘Pssyche’, Virgin Prunes’ ‘Baby Turns Blue’, and most of the recorded output of Theatre of Hate/Spear of Destiny.”

Another option much more to Eldritch’s taste than Le Phono was the Fenton. “It was the pub you went to before gigs at the uni,” he recalls. “Everybody thought fondly of the Fenton. Going back to the days when there was street fighting, the Fenton was very unwelcoming of Nazis and welcoming of the likes of us. The whole atmosphere was very politically charged and we were very clear which side we were on.”

Some accounts of Leeds in the late 70s and early ‘80s, make it sound like Weimar Germany. “It was not that glamorous,” states Eldritch. “It was more like Jubilee (Derek Jarman’s punk film). There was a ridiculous amount of violence and antagonism from a small racist element in the city,” states Langford. There were violent clashes between right and left, packs of neo-Nazi thugs on occasion marauding into Red pubs. Andy Gill had his nose broken in one incursion into the Fenton.

Leeds was certainly a cocktail of tensions: a regional centre for the British Movement and National Front and for anti-racism, rapidly rising unemployment and declining infrastructure, substantial Jewish, Carribean and South Asian minorities, 10,000s of (state-subsidised) students from out of town and a growing subculture of post punk “weirdos”, many of whom appeared to be neither heterosexual, nor vanilla in their tastes.

“Leeds was a hellhole, I tell you,” is how Gregory puts it. Horigan agrees that the risk of a kicking was quite high, so the (post) punks tended to limit themselves to places “where no-one gave you any shit.” Picking your route through the bottom end of town was key, since The F Club was midway between The Whip and The Adelphi, two pubs with a clientele of “right-wing nutjobs … who hated punk rockers and wanted to kill ya,” remembers Gregory.

This must have contributed to the tribalism and loyalty that The Sisters invited.

‘Alice’ was released as a 7” single in November 1982. “Floorshow”, an even better song, was the B-side.

The Sisters first gig afterwards was a foray into Birmingham’s pub scene at the Bournbrook Hotel in Selly Oak; Clint Mansell and Miles Hunt were in one of the support bands. Their second was a probe into the capital, supporting Aswad at The Lyceum Ballroom.

Neither provided instantly compelling evidence that their time as a “Leeds cult band” was coming to an end. In their hometown, in a parallel world of commercial success: Yazoo, Gillan and Simple Minds played the university the month ‘Alice’ came out, Duran Duran, the Queen’s Hall. The biggest Leeds event of the year had been The Stones in Roundhay Park in July, eclipsing even Queen’s Elland Road show in May.

Yet, by the end of the 1982, the impact of ‘Alice’ had become clear. “We started off thinking it was enough to be our version of The Fall,” says Eldritch. Our ambition did not stretch in any other direction. After ‘Alice’ it definitely did.”

‘Alice’ ushered in an epochal 12 months for The Sisters of Mercy: the ‘Anaconda’ single, the classic format of ‘Alice’ – a 12" single with ‘Floorshow’, ‘Phantom’ and ‘1969’; The Reptile House EP; a Sounds front cover, a BBC Radio One session for David “Kid” Jensen, first tours in Europe and the States; and ‘Temple Of Love’, their first Indie Chart No.1 in November 1983.

As ‘Alice’ marked the starting point of The Sisters’ rapid ascent, it coincided with the full-blown explosion of the subculture that would dominate their reputation and that of Leeds.

1983 was The Year Goth Broke.

Yet, in Chicago, in parallel with the rise of The Sisters Of Mercy, another pale, bespectacled tech-geek was mixing a primitive drum machine with distorted guitar. On the evidence of Lungs, Steve Albini also did not do his best work in the first year of Big Black but the shared intent with The Sisters is apparent: to make a post punk version of rock music that wedded distorted guitar with synthesised drums.

The Sisters, according to Michael Azzerad in Our Band Could Be Your Life, were “Albini favourites” and Big Black signed with a distributor specifically because it had put Sisters records out in The States. “That’s very flattering,” admits Eldritch.

Eldritch and Albini would both work out how to harness the squall of electric guitar to that “shuddering mechanoid backdrop” in ways that clearly connected them.

The intersection of The Sisters and Big Black, Eldritch with Albini, Leeds with the American Underground, offers a tantalising counter factual to the Goth’s smothering embrace.

In this alternative narrative, The Sisters Mk III should be credited with redefining the interaction between electronic and rock music, connecting the modernity of synthesized rhythm with the old-fashioned aggression of amplified electric guitar. ‘Alice’ and The Sisters’ run of singles that followed it should bookend the post punk history of Leeds with Gang of Four’s Entertainment!

In this nook of the multiverse, where John Keenan is a king exalted on high and post punk Leeds is indeed worthy of all praises, could we please also be upstanding for The Sisters of Mercy:

Mark Pearman.

Craig from The Expelaires.

An A Level student called Ben Matthews.

And Andy Taylor.

They were not born great, but they did achieve greatness, no more so when they put out ‘Alice’ in November 1982.

It was the end of the beginning.

With thanks to Phil Verne. The Sisters Of Mercy are on tour in the UK starting on November 19