On its initial release in 1995, Tilt was regarded more as deluded final words than some kind of new beginning for an erstwhile Walker Brother. Spat out into a 1960s-obsessed British musical landscape by a bemused record label unable to devise any cohesive marketing strategy beyond a handful of WTF interviews and a guest spot for the artist on that bastion of forward-thinking avant-cultural principles, Later With Jools Holland. Scott dutifully if resignedly submitted himself to howling ‘Rosary’ from behind clamped-on shades, peering out from the corner gloom of a TV studio and resembling a haunted pale sliver of blasted devastation forced to jump through the promotional hoops one last time. Tilt was filed under “wilfully unlistenable” and Scott was generally expected to retreat back into the darkness from which he had so briefly reappeared.

Over 20 years later and Scott is now almost as prolific in his output as he was in that golden late 1960s period in which so many wished him to stay. A steady stream of albums and projects have emerged, many carving themselves out of the template that Tilt first put forward to a horrified notional audience unwilling to accept that this could be the same Walker they’d heard crooning suddenly-fashionable easy listening staples. Yet, the few years which immediately followed Tilt found Scott involving himself more with fleeting glimmers of soundtrack work, almost as though he were piecing himself back together as a recording artist by applying himself to the cinematic motifs which had proven so influential on his early work. Ever The Moviegoer.

So, in amongst the aborted Bond themes and Bob Dylan covers for movie compendiums, Scott also produced a heavy chunk of instrumental soundtrack work for Leos Carax’s Pola X in 1999. While the film was an overripe and unwieldy slab of European art-house cinema, Scott’s soundtrack (which also featured contributions from Sonic Youth and Smog) demonstrated how determined he was to maintain the near brutalist textures and modernist compositional architecture of his most recent album. Pola X felt almost like a companion piece to Tilt and much of Scott’s continuing work has taken these dual records as their genesis.

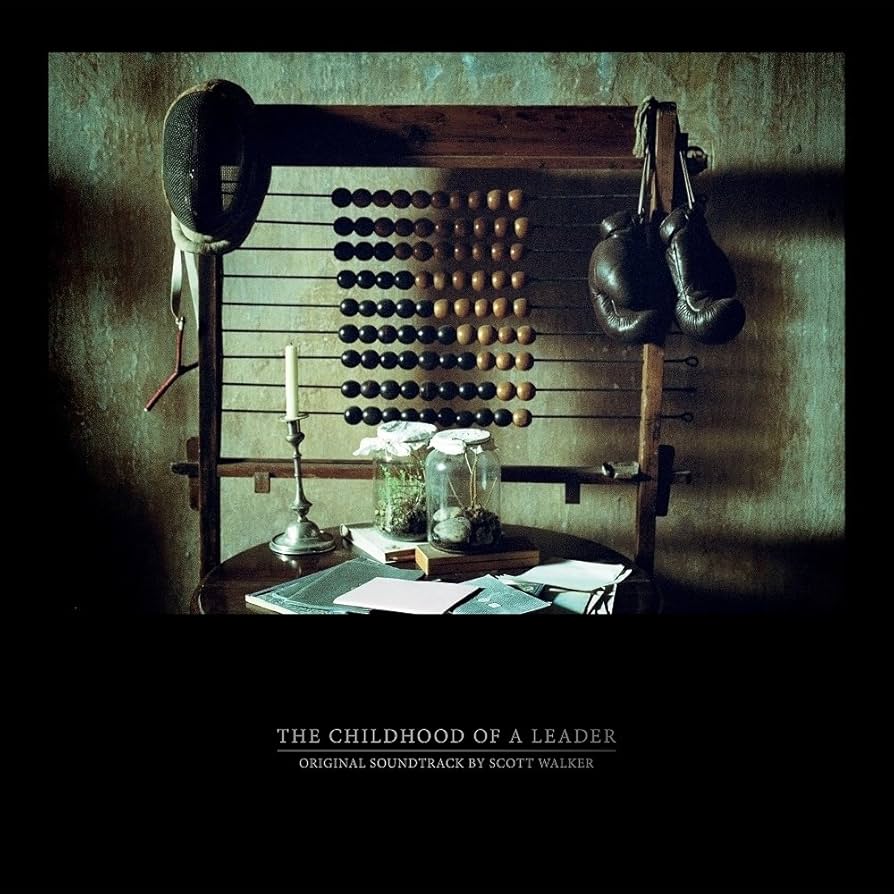

Similarly, this new soundtrack album for Brady Corbet’s directorial debut feels like an accomplice to 2012’s Bish Bosch. That record made it seem as though Scott had lifted his compositional technique to the point that being immersed inside one of the songs felt like inhabiting a three-dimensional spatial structure for some length of time; a non-linear narrative being constructed from the listener’s very presence within the piece of music. Similarly, The Childhood of a Leader soundtrack distils the narrative essence of cinema into a relatively short time frame built from musically segmented stabs and jolts. Many of these fragments are brief cues and asides which form together as one unified whole piece of music, similar to Scott’s 2007 release And Who Shall Go To The Ball? And What Shall Go To Bell?, designed to accompany a performance by modern dance company CandoCo.

While much of the music here is heavily indebted to Scott’s solo work of the past two decades (‘Opening’ with its churning saw-bone strings and horns that buzz like carrion flies, ‘Printing Press’ which slices through darkening silence with icy electronics), there are also, inside minuscule pieces such as ‘Cutting Flowers’ and ‘The Letter’, nods to the wide-eyed if frayed romantic modernism of Climate of Hunter and even Scott 3. It also displays the continuing relevance of cinema as a medium upon his work: although ‘Opening’ or ‘Finale’ wouldn’t sound out of place on one of his recent albums, it is also easy to picture Saul Bass titles accompanying their full-blooded dramatic evocation. The Childhood of a Leader opens up further notions on the increasing use of mise en scene within Scott’s music as well as positioning himself as a modern composer utilising cinematic techniques within narrative frameworks. It is an unexpectedly urgent addition to a master’s late period canon.