When Justin Vernon began playing ‘22 (OVER S∞∞N)’ amidst a surreal silence at Eaux Claires Music & Arts Festival in August, it seemed as though everyone present knew they were about to have something entirely ungraspable placed just before them. Vernon himself was visibly nervous, probably conscious that – for many reasons – the live premiere of Bon Iver’s third album, 22, A Million, might be difficult to come through completely unscathed. Nonetheless, he did.

Anyone who felt betrayed by the music that followed For Emma, Forever Ago probably fell in love with Bon Iver for all the wrong reasons; led astray by the soft whisper of ‘Skinny Love’’s snowy heartbreak rather than following the filtered, crooning voices of ‘Wolves’, or the vital bursts of ‘Creature Fear’ – the times that Vernon tried to push his soul out into the world instead of withdrawing into himself.

A less introverted, quasi-psychogeographic approach formed the basis of Bon Iver – the outfit’s self-titled second effort – a wonderfully-produced, algid exercise from someone eager to distance themselves from a tag of “lovelorn folk singer” that was never really wanted. Big tours, Grammy Awards, SNL parodies followed the release. Panic, anxiety, treatment. Then, silence. “Winding it down. I look at it like a faucet. I have to turn it off and walk away from it because so much of how that music comes together is subconscious or discovering. There’s so much attention on the band, it can be distracting at times. I really feel the need to walk away from it while I still care about it. And then if I come back to it – if at all – I’ll feel better about it and be renewed or something to do that,” he told 93.8 the Current in September 2012.

It took Justin Vernon five years and a dire trip to Europe to get back at it.

22, A Million was born out of the desire for something finite – an ending. "It might be over soon," repeats over and over on its opening track – an act of self-conviction, a mantra, a self-fulfilling prophecy; the loneliness of an off-season vacation just an excuse. It is the sound of a musician coming to terms with the excruciation of making art and exposing himself without armour. The understanding that the spirit is not enough, it’s the body they –the audience, the fans, the press, the industry – will always lay claim to: as a relic, as a trophy, as a proof of faith.

"Faces are for friends – Friendship is for safekeeping – Family is everything," Vernon even had it printed in the album credits, a reminder to the vampires at the door of exactly who is in charge, and to himself of what’s really worth preserving.

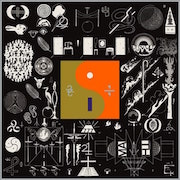

In Bon Iver’s resurrection, now, the lights are dim, the lineaments shielded by darkness, the voice heavily processed: the solution isn’t found in distance, but in a shroud. This is a world of numbers – abstract entities that regulate concrete existence; a taijitu with asymmetrical yin and yang controlled by imbalanced dualities, beginning with life and death themselves. Finite / infinite, known / unknown, multitude / solitude.

The sound of the future is made of digital beats and analogue filters – of new instruments (like the Messina, invented by Vernon and his engineer, Chris Messina, or the Jennette) and old saxophones; it is borrowing others words and sonorities to layer upon ones self, duplicating voices to create a crowd from a single person. Forging new languages.

Listening to 22, A Million feels like hearing the sound of Deleuze and Guattari’s incipit from A Thousand Plateaus: "Since each of us was several, there was already quite a crowd. Here we have made use of everything that came within range, what was closest as well as farthest away. We have assigned clever pseudonyms to prevent recognition. Why have we kept our own names? Out of habit, purely out of habit. To make ourselves unrecognisable in turn. To render imperceptible, not ourselves, but what makes us act, feel and think. Also because it’s nice to talk like everybody else, to say the sun rises, when everybody knows it’s only a manner of speaking. To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied."

The stomping, urban chaos of ‘10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⊠ ⊠’ is followed by the metallic silence of ‘715 – CRΣΣKS’; The folk sounds of their origins swerve back into earshot on ‘29 #Strafford APTS’, a duet with longtime collaborator S. Carey. The smooth piano opening of ‘33 GOD’ soon turns to synthetic turmoil: a God of his own theogony, transforming the 666 into a triple spiral, subverting its meaning.

‘8 (circle)’, though, marks the zenith of the record: the perfection of the shape recalled in the title reflected in the music, a masterful balance of full voice, vocoder and falsetto meeting beats and saxophones, exposing Vernon’s long-held love for Bruce Hornsby’s melodies. It’s not the sound of Vernon, in the end, but the voice of Fionn Regan – sampled from ‘Abacus’ – that signals the end. The most confessional and piercing tune of the album, ‘00000 Million’ is a reflection of a place where "the days have no number" – the void, the omega, the perfect point for a brand new start.