The ‘father of modern optics,’ 11th-century scientist Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), was quoted as saying: “If learning the truth is the scientist’s goal… then he must make himself the enemy of all that he reads.” One of Alhazen’s theories, still puzzling scientists today, was why the moon looks so big when it is low in the sky appearing over the horizon, when compared to its apparent size at the zenith, higher up in the sky.

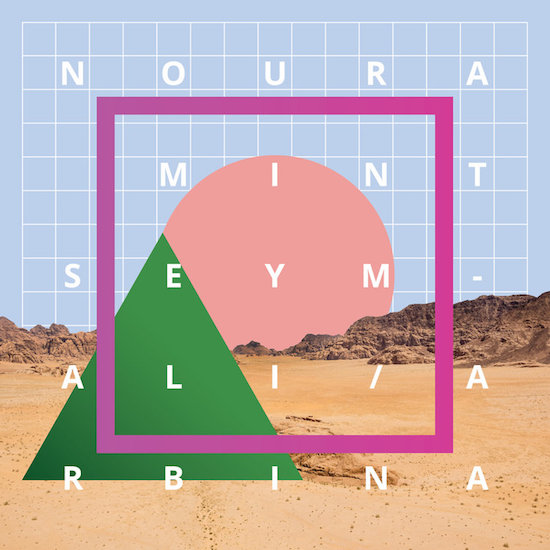

Alhazen believed that sight was only possible through the reflection of light rays before entering the eye and his “moon illusion” comes to mind when examining the cover of Noura Mint Seymali’s new album, Arbina. A pink orb appears over a desert landscape, framed by a cube, with a strategically placed pyramid in the foreground. This alignment along with the grid template that maps the skyline questions the sense of size and perception.

In traditional Mauritanian music men play a banjo-like lute - the tidinit - and women play the harp-like ardine, similar to the kora played in Mali. The music played by Seymali and her group follows a tradition of folk music that dates back hundreds of years, but it has never sounded quite like this molten form of sunbaked Saharan psychedelia. Their modern take on griot music is made with the classic rock band set up of guitar, bass and drums, with Seymali on ardine and vocals, which they describe as playing the music of the "Azawan” – the music of the desert.

On Arbina – the group’s second album following 2014’s Tzenni – Seymali’s husband Jeiche Ould Chigaly has replaced the tidinit in favour of electric guitar, modified to replicate Moorish scales by adding additional frets on the neck, adding to the mystique of his playing, which twists and turns reaching dizzying heights throughout, fingers dancing in a whirlwhind of inspired axe-wielding wizardry.

Opener ‘Arbina’ is doused in Chigaly’s warped licks, with Seymali repeating the title – a name for God – as she calls on women to make the most of available health care, following the death of her mother to breast cancer: “The sickness is preventable, if you get an analysis early you will be okay and without regret.” Seymali’s vocals can transform any line into a spellbinding command as she holds notes seemingly endlessly – a skill apparently developed as a young girl by pushing her voice to breaking point and, in doing so, opening up new musical chambers deep within from where to draw additional vocal power.

‘Mohammedoun’ follows with Ousmane Touré’s deceptively subtle bass throbs forming fluid foundations in a maze of complex musical patterns with drummer Matthew Tinari over underlying dub-like siren frequencies. The intensity is taken higher again on ‘Na Sane’, as Seymali lyrics address the group’s alchemy, “The music of the band, the Azawan, is blending well with my song, Protect us from bad enegry, Help us preserve the vibe”. The reflective ‘Suedi Koum’ brings Seymali’s ardine forward in the mix, as she sings: “We appreciate the music you’ve played, And that you have sung this song right now, You have left nobody untouched, You have blown all of our minds!”

Seymali and Chighaly have been playing music together for more than 18 years and their musical lineage goes back much further, both coming from griot families. In Noura’s case some 10 previous generations have been griots. Their musical relationship mirrors that of her father, the tidinit player Seymali Ould Ahmed Vall who performed with Seymali’s stepmother, one of Mauritania’s most loved pop stars Dimi Mint Abba, known as the “Diva of the Desert” – who Seymali also toured with as a backing singer when she was a teenager. Before joining the group Touré also played music with Seymali’s father, while Senegal-based Tinari, who also produced the album, has been working with the group since they met at a music festival in Dakar in 2009.

Seymali revisits her family’s musical roots with ‘Richa,’ written by her father and performed by her stepmother throughout her career. Different versions of the track from over the years show how the musical backing moved from traditional to more keyboard-based instrumentation in the 1980s, and Seymali and her group again update the sounds in their own style for today, within the traditional structure. Seymali’s playful and searching vocals poetically describe the “Word of truth living in between the flickerings of visions and the folds of the imagination,” in praise of their homeland.

‘Ghlana’ shows another side, or rather slide, as Chighaly woozes bleary countrified licks out of his guitar. On album closer ‘Tia’ Seymali returns to the theme of health as she calls on the lord to send an unwell friend or relative “blessings so that she may forget her sickness”.

Alhazen’s earlier dark room camera obscura experiments brought an understanding of how light could appear out of nothing in what would later form the basis of photography, as he observed that light coming through a tiny pinhole would travel in a straight line to project images on, for example, a wall opposite. In the studio Seymali and her group prove as effective at creating another atmosphere altogether with their sounds. On ‘Soub Hanak Seymali’ sings, “It’s the tent of the griot, Where there is always music, You are the masters of the music, Instruments become your slaves, And you masters of these instruments.” As the line between the musicians and their instruments blur, the different parts become a whole, captured in the recordings.

Noura Mint Seymali spoke to the Quietus by email to tell us more about the album:

How was the development of Arbina shaped by the reaction to Tzenni by listeners around the world? Has it changed the way you compose? How have you approached this differently?

Noura Mint Seymali: Our sound has solidified a lot since Tzenni. At the time of its recording in January 2014 and July 2013 we were only just beginning to experiment with our current format. Arbina comes after several years of touring with the band, growing, learning and refining its sound. A positive reaction to Tzenni was certainly encouraging and kept us working hard. That said, the compositional process has not undergone any radical changes, but we have grown more efficient in workshopping new songs and finding what arrangements work.

How has the dynamic of the band developed after touring?

NMS: In general we’ve gotten much more used to playing larger festival stages and working in a pop context. The rhythm section has gotten tighter and more confident, which in turn has allowed Jeiche and I greater freedom to stretch out. As a band we’ve all grown more comfortable with the music and with each other; standard benefits of practice and repetition.

Why record in New York?

NMS: The timing and geography simply matched up and felt right. In February-March of this year we had a long North American tour with an open window at the end of it, so we decided it would be the opportune moment to capture the band in full swing, revved up and in high gear after some time on the road. We already had a working relationship with the studio in Brooklyn and had an excellent experience recording there for Tzenni, so it was quite natural to return to the same place given the time. Tracking goes much more smoothly when there is pre-awareness of what the music is and how to best go about capturing it. Tony Maimone (technician) and Matthew Tinari (producer) both came in with lots of ideas and were able to really hit the ground running.

You have spoken about creating a new genre of “Azawan” music from the desert – how do you define this? And are other artists out there playing similar music in this way?

NMS: Perhaps it may be defined as pop music based on Moorish tradition. "Azawan" is a term in Hassaniya that refers to the ensemble of instruments and musicians that play in Moorish traditional contexts. Ardine, tidinit, t’beul [drum], guitar, vocals would all be considered part of the "Azawan." Our first two EPs with the current band were titled “Azawan” and “Azawan II” as a sort of nod to the traditional core that we were expanding upon. The terminology is not the most important thing, but “desert blues” is not very specific. Many cultures have more specific genre names; “rai” in Algeria, “mbalax” in Senegal, etc. Why not “Azawan” for Moorish pop from Mauritania?

To be honest, there are not really any other bands in Mauritania with the same approach, but perhaps there will be someday. It’s not easy to make a living doing pop music in Mauritania and most Moorish musicians opt to take the easier path of playing for the market that already exists; weddings and ceremonies. We hope to foster growth within our community and show people that it is possible to succeed, innovate and reimagine the music.

On this album guitarist Jeiche Ould Chighaly is not credited with playing tidinit as on the last album. How has the electric guitar been modified to play the Moorish scales?

NMS: Jeiche has been playing mostly guitar while on tour and the album is a reflection of that. However, he remains active on the tidinit and his guitar playing has always been greatly informed by it. The fretboard of Moorish guitar is modified with added frets to get the quartertones needed to play our music properly. The electric guitar provides a wider palette of sounds and is a bit easier to work with on loud festival stages. There’s a bit more freedom than with tidinit.

How did you find touring the last record so soon after having a child? I remember a moment when you left the stage at a Cafe Oto gig in London to check up on your young baby backstage.

NMS: It was a blessing to tour with my son, Youba, despite the obvious challenges. Alhamdulillah, we did not find any problems. It is very helpful that his father is also there with me and the entire band was very supportive. You would be surprised how kind and accommodating different promoters and organisers can be, some really going out of their way to help us find someone to watch him while we performed. Youba loves music and prefers to watch the show out front and see us rather than be backstage, but not all venues can allow it. His favourite song is ‘Richa’. The band always jokes about the hidden advantages of travelling with an infant, such as early boarding on flights. Youba visited over 18 different countries with the band and was there in the studio for the entire recording of Arbina, both sessions. Someday we will show him all the places he’s been when he was just a baby!

Is the process of choosing material for an album different to the music performed at weddings? Are the songs shorter? Are the arrangements different for inclusion on a release?

NMS: Yes, a wedding and an album are two very different scenarios. Songs are shorter on an album and the music’s audience can be everywhere, instead of at a wedding where the focus is on the ceremony. It’s very different.

You used Whatsapp group chat as a forum to help with the composition on one of the songs on the new album, ‘Mohammedoun’. How did that work? And how does this fit in with the oral tradition of griots passing on stories and songs through storytelling?

NMS: ‘Mohammedoun’ is a song that I wrote myself but there are some lines I developed while contributing to a WhatsApp group for women where we sing Medah (praise songs for the prophet). You can pose questions to the group or answer something someone else has said or sung. That group is for praise music specifically among women. Another WhatsApp group I’ve been a part of is a family group for the descendants of Sedoum Ould Njartu, an ancestor to both the Abba and Ahmed Vall families, which includes Dimi Mint Abba and my father’s line Seymali Ould Ahmed Vall. In both instances it is a group conversation where ideas can are exchanged back and forth.

Do you see this as a way for the next generation of musicians and griots to engage in music and keep these traditions alive?

NMS: Music is about communication and I imagine the next generation will continue to create using the forms of communication that are available to them.

‘Richa’ is a song written by your father and previously performed by your stepmother. Why did you choose to include this song and how is it special to you?

NMS: ‘Richa’ is a classic song that all Mauritanians know. I’ve always enjoyed performing it and we’ve played it on tour with the band many times. It always gets a good crowd response and has become part of our core repertoire. Since we had no recorded version of it we decided it would be great to include on the album.

You also performed this song (‘Richa’) with The Orchestra of Syrian Musicians as part of a recent Africa Express tour. How did this come about and how was the experience of playing with Syrian musicians?

NMS: ‘Richa’ is a song that is easily intelligible for Arab musicians because of the melody and the feeling is suited towards a classical orchestra because of the composition’s grandness. When preparing the concert repertoire with The Orchestra of Syrian Musicians, ‘Richa’ was an obvious choice for a song that might work well as a collaboration. ‘Tzenni’ for example would not have fit as well.

What inspires your lyrics? And when do you know the moment of inspiration, musically or lyrically, is something to persevere with?

NMS: This is a hard question to answer; when you know something is right, you know it’s right.

Among subjects covered on the album are illness and the role of faith in your life and influence of the singer. Why where these messages important to include?

NMS: Faith is at the centre of my life and so it is very normal to draw on it as a source of inspiration in my music. It touches everything. The title track ‘Arbina’ addresses women’s health and encourages women to get early screenings for breast and uterine cancer. It encourages them to do what they can. My mother died of breast cancer and so it is a topic with special significance to me.

Sëbeu is also mentioned in the themes of the album, what is this?

NMS: This is the idea of one’s earthly duty or initiative in the service of destiny. It’s doing everything that can be done for oneself and one’s situation as an act of faith. Using your human power to do what’s best and leaving faith for ultimate outcomes in God. ‘Arbina’ mentions early screenings for women as an expression of this, it’s the only thing we can do, so we must do it and then let God decide.

Now the album is out, what next for the group? Are you touring?

NMS: Touring. Lots of it. Europe, America, Africa, the Middle East. May God help us make it through all of it in peace!

Noura Mint Seymali’s new album Arbina is out on 16 September on Glitterbeat. Click here for full list of live dates