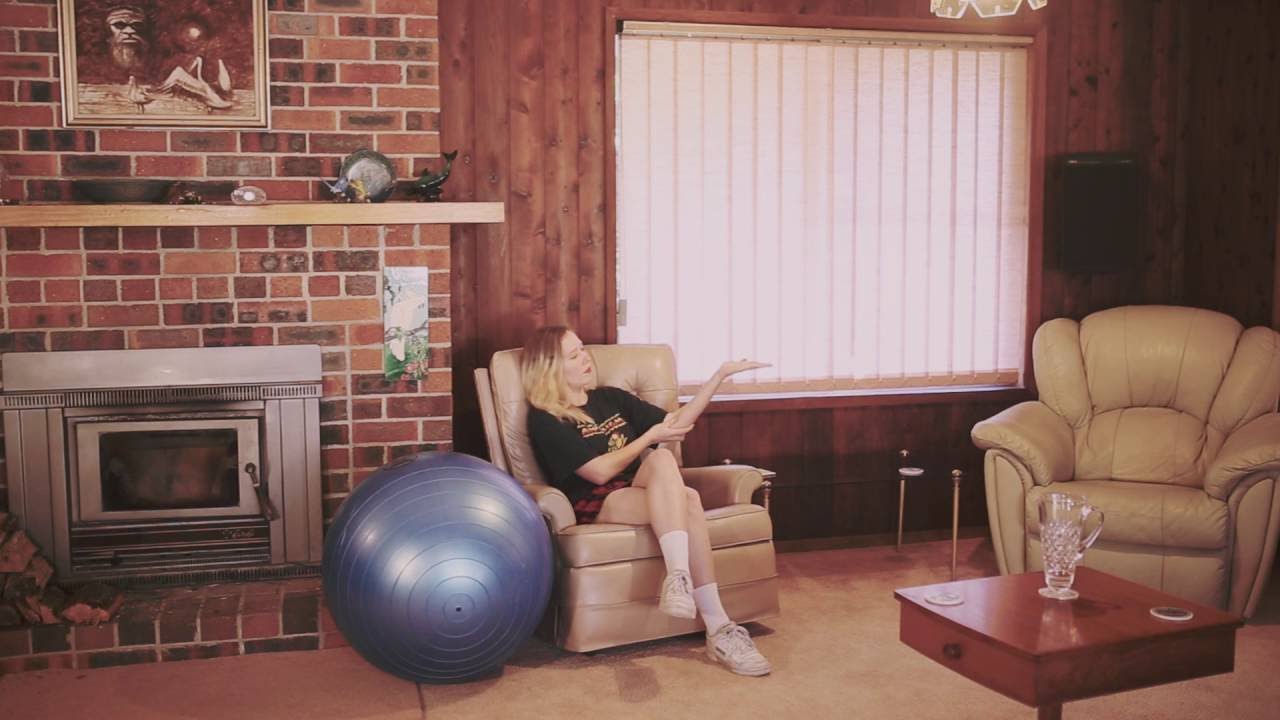

Photograph courtesy of Nick McKinlay

As I begin my conversation with Julia Jacklin, she tells me that she’s sat in front of a fake fire at her parents’ house. This setting seems just about fitting for the Australian singer-songwriter, whose videos for her songs ‘Pool Party’ and ‘Leadlight’ are knowingly, though never smugly or ironically, imbued with senses of kitsch and nostalgia, played out in carefully choreographed, period-detailed style. The songs around which they are wound sound at first like swing-time ballads, all cyclical chords and cautious percussion. Yet upon closer inspection, they too are exactingly-observed vignettes, eloquent meditations upon knotty subject matter, the likes of which populate Don’t Let The Kids Win, Jacklin’s solo debut, released on Transgressive in October.

Jacklin, who grew up in the Blues Mountains region of Australia, honed her craft as a member of Sydney-based outfit Salta, playing Appalachian folk-style songs with her high-school friend and creative foil, Liz Hughes. Subtle traces of that project can be detected throughout Don’t Let The Kids Win, with the kind of interwoven harmonies sung by Hughes and Jacklin central to Salta’s sound forming key moments on the solo record.

At the same time, the LP is a refocusing and development of her practice. Written while Jacklin worked in an essential oils factory in a Sydney suburb and recorded with producer Ben Edwards in New Zealand, it’s more brazen, straightforward and muscular than her work with Salta, and focuses on Jacklin’s preoccupation with looming maturation and an awareness of time passing by.

Your website says that as a child you were taught classical-singing technique and were first turned onto popular music by Britney Spears. How do you think these formative experiences are made manifest on Don’t Let The Kids Win?

Julia Jacklin: I think that I’m really grateful for having a classical background. I was very resistant to it, but I think that kind of discipline and focus on vocal technique has helped me a lot and informed the way I sing now. And having something to rebel against was good as a teenager.

Britney Spears was a big moment for me. I was in France with my family and I was watching this documentary on TV as it was the only thing that was in English, and she’d achieved a lot by the time she was 11, a lot of dance awards… It was a really early moment in my life when I was like, "Okay, you have to work very hard if you want to produce anything." And that stuck with me.

The sound of the album is often rather grand and panoramic in scale – would it be fair to say that your upbringing in the Blue Mountains and New South Wales might have contributed to this?

JJ: Well, I had a pretty small, suburban upbringing, with limited artistic opportunities. So I guess I kind of tried a lot of different things, like dance, musicals and classical singing, and I was pretty terrible at all of them. It was important to me to move to the city and begin to understand music scenes. That was the first time I started writing songs and meeting other musicians. I started playing with a lot of people from home in Sydney, and we still play together today.

Do you take elements of those experiences with other art forms and apply them to your current practice?

JJ: I don’t know really. I’m a pretty terrible dancer, but I definitely enjoy directing my music videos, and maybe something came from my attempts to act and dance.

Can you take us through your approach to video direction? Does it overlap with your approach to songwriting?

JJ: I’ve realised that I think about videos in the same way as I think about writing a song. I make sure that the choruses match visually, and the verses vary, just like the song. I think it’s easiest for me if I just find a really cool space, and then I imagine something happening within that space. For the one for ‘Pool Party’, I just found this beautiful, decked-out ’70s house in the Blue Mountains, and for ‘Leadlight’ I went back to my old high-school hall.

You’ve spoken about the significance of your collaborations with Liz Hughes. To what extent does your songwriting or approach to the production of music remain a collaborative process?

JJ: I didn’t collaborate much on this record at all. I’ve heard a lot of people say that about their first releases – they hold everything really close because it’s their first statement of who they are. Once you put that out there you can let go a little bit and let other people in. But I play in another band with Liz, in which we’re all songwriters.

Do you feel your solo and collaborative projects inform each other?

JJ: Well, in the other project I’m the lead singer but I don’t play guitar, and that’s forced me to become more confident on stage, and to understand the responsibility of making sure the audience is having a good time. When you first start playing you’re just there on the stage with your head down, like, "Well, if you like it you like it, there’s not much I can do…" Whereas sometimes if you actually engage with the audience it’s a very different experience. It’s good to learn that.

Did you approach the recording process differently from your work with Salta? Did the songs evolve in the studio?

JJ: Salta was the first project I ever recorded with so I had no clue what was going on! That was my first experience with the recording process so I was pretty confused and nervous the whole time. Most of the songs were pretty much figured out before I got to New Zealand but there were definitely some additions made in the studio when I just felt like they weren’t quite working. Ben and I recorded a whole different version of ‘Pool Party’ on the first couple of days, super upbeat and strange. That evolution now lies on the cutting-room floor after we went back to the original version.

Although many of the songs on the record are quite stark, for me the key to the album lies in its fine details, such as the backing vocal arrangements on ‘Leadlight’ or the tremolo guitar flourishes on ‘Motherland’. How much importance do you place on such details in relation to a song’s overall meaning and structure? How did they feature in the recording and production process?

JJ: I think those elements are really important to lift a song. I made the album in three weeks in New Zealand, and I think a lot of those elements came from us having the time to muck around and see what worked. The backing vocals for ‘Leadlight’ were just a 2am last-ditch addition. I had this idea of a choir coming in at the end, but there was only two of us and I didn’t know Ben [Edwards, producer] sang. But I left the room for a minute and then he was all set up in the studio belting it out.

Your album is partly a reflection on growing older and feeling a sense of nostalgia for youth. Was a desire to explore such feelings a conscious focus for you when you wrote the songs or did those themes seep into your writing more organically?

JJ: It came from genuinely feeling that way and needing to express it. A lot of my friends are around the same age, in the same career, all of us feeling the passing of time quite heavily.

The music industry has always been, to an extent, a cult of youth. Do you feel that, due to this, anxieties about ageing and senses of nostalgia for your younger years might affect songwriters more acutely than people who work in other industries?

JJ: Absolutely. It takes so long to get good at this, to learn an instrument and get to the point where your writing is reflective of what you want to express, and you need life experience. By the time you’ve done all that you think, "Shit – time is passing, and what have I done?" You worry that you might not have enough time to say what you want to say, and that once you get to a certain age people might not care what you have to say.

So how does it make you feel as a songwriter who deals with these themes in your mid-twenties to see songwriters continuing to produce work well into later life? Leonard Cohen, for example, has just announced that he will release a new album at the age of 82.

JJ: It inspires me, but I wish I had more female role models to look up to that are still writing at that age. Cohen does inspire me but I’d like to see more women of that age putting out stuff that people want to hear. Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton, Kathleen Hanna and Fiona Apple are still putting out great stuff. I hope that I can be as strong as they are when I get older.

Did you find that over the course of the album you came to terms with the ageing process and the idea of time passing by?

JJ: I don’t know if anyone ever really comes to terms with that, right? I think it’s definitely stopped keeping me up at night but I’m guessing that’s going to be an ongoing struggle. Recording my first album before I was 25 was a life goal so achieving that made me feel better.

Don’t Let The Kids Win is out on October 7 via Transgressive. Julia Jacklin plays The Lexington in London on August 31 before touring; for full details and tickets, head here