I could write thousands of words about Brexit to add to the thousands that have already been written, lamenting this closed-up-quick-to-the-battlements-lock-the-doors atmosphere we find ourselves in. But I’m not going to. I’m going to put my energy into what I always have: promoting translation, or in other words, promoting intercultural exchange and the values of openness and difference.

My first instinct was a practical one, supporting indie publishers who publish translations, but I still had a cloud of doubt hanging over me: Is literature really powerful enough to fight what we are facing? At a reading and discussion a few weeks ago I found myself asking halfway through my slot: What good are writers and words at times like this? I asked the same question a week later at another poetry evening I was reading at where Steven Fowler was also reading. Fowler performs and hosts poetry events internationally, he curated the first European Poetry Night this year, and he curates The Enemies Project; a series of events that partners up poets from different countries and of different nationalities to work and perform collaboratively. To end his piece on that night, he asked everyone to “write a farewell message to your own continent” by writing a note of condolence in a concertina book he’d been given as a present in China, while Jacques Brel sung ‘Ne me quite pas‘.

A few days after that, I gave a talk on translation as part of a series organised by Fowler at the Wellcome Collection for their States of Consciousness season. What I found I wanted to say, what I hoped I made clear, was that translation – like any kind of writing – has the potential to be a very human and humanising endeavour. Language was so misused and weaponised during the referendum, perhaps we find ourselves as anti-xenophobic pro-Remain writers and translators trying to cancel out or dethrone that language with our own.

What can’t be quickly forgotten in this brushing down and getting on with things is hate crime. Racist and xenophobic attacks rose staggeringly after Brexit was announced. I don’t have to tell you that Brexit didn’t make people aggressive, violent racists: it just normalised and legitimised pre-existing irrational fears and made racists and xenophobes feel comfortable performing that fear in public. This is something comedian Ava Vidal echoed in her interview about post-Brexit racist hate crime on Channel 4 News, where she also said that a new development she’d noticed is that hate crime is now not only against people of colour, but also white immigrants, primarily Polish people.

There are almost 800,000 Poles living in the UK, the vast majority settling here after Poland joined the European Union in 2004. Polish people living here, however, is not a new phenomenon: over 200,000 Polish people moved here after the Second World War, meaning there we have a substantial Polish and British Polish population across multiple generations.

I’ve seen a wave of Polish culture gaining visibility over the last couple of weeks, some of it a pronounced, conscious (some of it unconscious?) reaching out, an elevation to outweigh the negativity of a few bigots by various platforms: Granta magazine published two poems by Grzegorz Wrówblewski translated by Piotr Gwiazda; Asymptote published a non-fiction piece by Mariusz Szczygieł translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones (her name is going to come up a lot in this column) as well as an article-interview with visual artist Jakub Woynarowski translated by Beatrice Smigasiewicz; Publishing Perspectives ran an incredible interview with novelist Zygmunt Miłoszewski & translator Antonia Lloyd-Jones; The Quietus wrote about the rise of Polish electronic music; the Translating Theatre project has been working on Polish-German playwright Piotr Lachmann’s Hamlet Gliwicki, written about here on Exeunt. If you’d like to read Polish literature in translation by the way, Litro had a Poland issue a couple of years with a Top Ten of some of the best translated Polish books (let’s hear it for Antonia Lloyd-Jones everybody!). I could also direct you to James Hopkins’ Top Ten English translations of Polish books from The Guardian, but the article doesn’t name a single translator. Ok, I will anyway, for the sakes of the original writers.

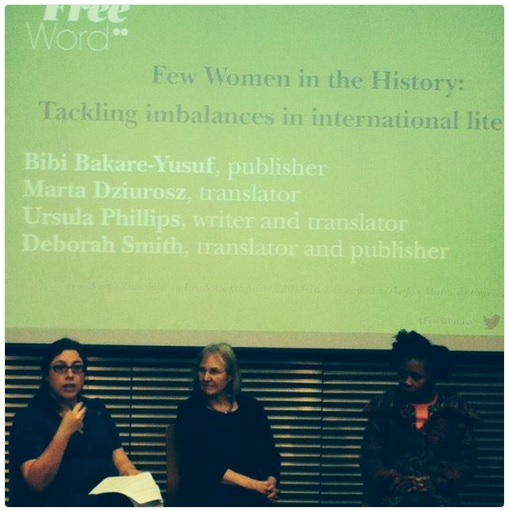

English-to-Polish literary translator Marta Dziurosz, who is Translator in Residence at the Free Word Centre in London, wrote a moving piece on being an EU immigrant living in the UK post-Brexit for English PEN. After numerous on and off the record conversations around translation with her, many of which around the idea of what being a translator in residence can achieve and her desire to translate Polish literature into English despite being Polish, it felt like the right time to interview her.

Dziurosz was born and grew up in Poland, but her father started working in Greece when she was six or seven: “I’d say migration has always been part of my experience”, she says. Books, music, poetry and cinema were very important at home and her parents could have been considered part of the Polish “intelligentsia”.

She went to primary school the year after the socialist regime ended, which she considers lucky “in that we started English lessons right away, which wasn’t a rule back then – although I’d started learning English at home even earlier than that”, and after her undergrad degree she did an MA at the Institute of English Cultures and Literatures, part of the University of Silesia in southern Poland.

She describes this course as “a revelation: modern, interdisciplinary, mostly fascinating” and she explains that “apart from the more traditional subjects concerning history of literature, composition, various aspects of linguistics etc., we dabbled in gender and body studies, multimedia, postcolonial theory, very modern literary theory” resulting in her MA thesis being on the smell of spices in erotic, religious and postcolonial literature. I interviewed her over email (which is a shame because I love meeting and talking with Marta in person).

You’re a literary translator predominantly from English into Polish and you also work for Pan Macmillan – how did both things come about and how do these roles complement one another (if they do)?

Marta Dziurosz: I was going to do a PhD, but that fizzled out for a few reasons. Who knows, maybe one day I’ll just write a book. What I did instead was a year-long literary translation course at the UNESCO Chair of Literary Translation and Intercultural Communication – what a mouthful – in Kraków. Again, I was very lucky – I got my first job as a literary translator into Polish through my amazing tutor, and then worked pretty much non-stop for about six, seven years.

The first literary translation job I found on my own was through a book fair in Poland – I introduced myself at the stall of every publisher, left them some hand-made materials that, in hindsight, were probably entirely embarrassing, and one of them bit. I’ve translated something like fifteen books, taught a bit, did interpretation.

I was still working as a freelancer when the opportunity came up to move to Swansea, where I lived for a year. I still love Swansea and it was a nice, gentle way to emigrate. Then I got hit in the face with London and realised literary translation into Polish doesn’t really cut the mustard money-wise, so found a job at Pan Macmillan, in contracts, and combined the two for a good while. I draft and negotiate most of their translators’ contracts, which is an interesting peek behind the scenes and gives me the chance to mediate between the two sides of the deal. Also just being in publishing, meeting editors and getting to know the scene is very helpful.

Interestingly, you’re also emerging as a Polish to English translator. Some people in translation can be a bit funny about translators translating into a language that’s not their ‘native’ language/mother tongue. What led you to want to translate into English and what do you make of the ‘non-native’ wariness?

MD: Yeah, Michael Hoffmann once said something about not trusting people who do it both ways. That it’s like drinking the bathwater. What I will say is that I’m getting increasingly confused about who a native speaker even is – this is what we talked about during my panel on that topic at this year’s London Book Fair. I’m not some unbelievably successful bilingual translator – I’m still figuring out how to have a book-length literary translation into English published. But I’ve been functioning bilingually for most of my academic, creative, professional and personal life, and I’m also angry about how the mainstream – or maybe just the most visible – Polishness is starting to represent itself abroad.

I feel comfortable mediating between the UK and Poland, and now that I’ve spent all this time trying to acquaint Poles with the UK and its language, I’d like to have a chance to show a bit of Poland to the UK. Try and question some assumptions. Introduce voices that might be surprising, yet at the same time strangely familiar. I feel my job as a bilingual translator does not differ from the task of any other translator – so I’m learning as much as I can to be able to do it well and hope people can stomach my unpronounceable surname.

You recently wrote about Brexit for English PEN, how has being Polish in London in the time of Brexit made you think about the ‘translation project’ and your identity in general?

MD: It just made me think I need to keep doing everything I’ve been doing, but twice as hard. I had a bout of the Brexit flu when things felt really rather awful and I was doubting many of my life decisions, but came out the other side more keen to speak to people, to read and write, to make connections. To seek out others who straddle cultures, to find those places of intersection, which I’ve always found most interesting.

Although I am aware I have masses of privilege and my experience was relatively easy, I’ve always called myself an immigrant and that is my identity. I was even thinking of making a T-shirt to that effect in the aftermath of Brexit. The UK is now going to have to redefine its attitude to free movement and immigration, which means if you feel ashamed to be British, now is the time to act and prove there’s nothing to be ashamed of.

You’re Translator in Residence at the Free Word Centre. You interviewed me about my role (as part of your role!) as a TiR and briefly talked about it as a political, activist role. Could you tell us a bit about the projects and events you’ve organised and run for your residency and more about your motivations?

MD: My motivations are mostly very selfish! The description of the role was absolutely open, so I did things I felt it would be useful for me to know how to do, so that I could later continue to promote literature in translation: I organised and chaired some public and semi-public events, talked at universities, did some work at schools, met with reading groups, commissioned and provided online content and so on.

The unifying theme, I think, might be something I mentioned during my interview for the position: rooting for the underdog. Looking at things that are underexplored – or looking at an angle. Bringing people together. We talked about translators’ contracts, translating women writers, translating scent, illiberal democracy, we launched a graphic book on immigration, and much more.

There was a Polish presence in most of these. I was very inspired and helped by people who are much more experienced in their fields than I am: Sophie Wardell from Free Word, Magda Raczyńska from the Polish Cultural Institute, Polish translators like Antonia Lloyd-Jones and Anna Hyde. It’s been a very steep learning curve, very collaborative, very eye-opening.

Poland will be guest of honour at London Book Fair next year, is Polish literature having ‘its moment’?

MD: I sincerely hope it will! So many great people here in the UK, the US and other countries have been working for years at bringing Polish literature to the attention of English-speaking readers that there’s a strong foundation already, Polish cultural organisations are helping and the British Council obviously have masses of experience with organising the Market Focus for each year.

As is sometimes the case, I think there is some disconnect between what the upper echelons back in Poland want to promote and what the publishers here would presumably want to buy, but I’m sure a wide range of titles will be represented. It will be very interesting to see which ones resonate with the local public. We will do our best to sustain the Poland-related activity after LBF.

Polish literature has everything: crime and thrillers (Zygmunt Miłoszewski, Marek Krajewski and upcoming from Katarzyna Bonda), fantasy (Andrzej Sapkowski), non-fiction (Hanna Krall, Wojciech Tochman, Witold Szabłowski), literary fiction (Andrzej Stasiuk, Olga Tokarczuk, Magdalena Tulli), poetry (Zbigniew Herbert, Tomasz Różycki, many excellent female poets collected by Karen Kovacik in Scattering the Dark), great mid-century classics and so, so much more.

There’s such a massive Polish community in the UK – you can have some delicious Polish kefir, read a book from there and get to know us a bit better.

What have been your favourite books that you’ve translated into Polish and what are the major issues or quirks of translating from English into Polish?

MD: I wasn’t exactly in a position of being able to pick and choose – but I enjoyed the challenge of the many different speculative fiction stories collected by George R R Martin in Down These Strange Streets and Stella Duffy’s Purple Shroud about Empress Theodora. I liked Caroline Alexander’s account of Shackleton’s journey with Frank Hurley’s original photographs. Xiaolu Guo’s short stories written for Free Word’s Weather Stations project were also interesting, very ethereal.

I’m not sure I can speak about the quirks of translating into Polish in a way that is even remotely interesting? A potentially very pesky one is that nouns, adjectives and verbs can have different forms depending on gender, so, for example, translating Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body must have been tricky – it was impossible to tell the story from a point of view that wasn’t gendered, without resorting to potentially unnatural acrobatics. In the Polish version the narrator is female: apparently that was Winterson’s call.

And your favourite as-yet-untranslated Polish books?

My three completely self-indulgent choices for untranslated books are:

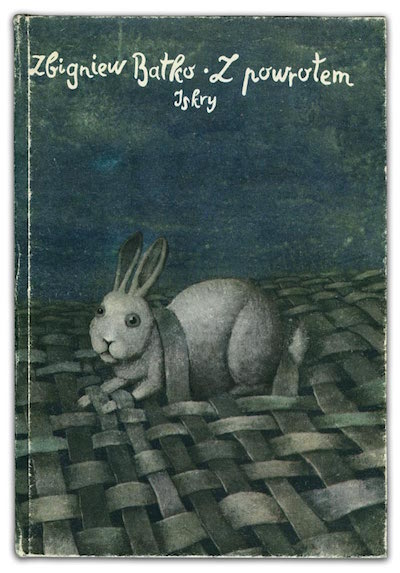

Zbigniew Batko’s Z powrotem (Way Back). The most important book of my childhood and youth. Written by a translator! You can read it as a child and be entertained by the surrealist humour, then revisit it every year of your life and discover new things in this parable about a Rabbit, a Horse, a Penguin and an Elephant: literary allusion, political satire, class conflict. The language absolutely dances across registers, it’s masterful – and deviously funny, too.

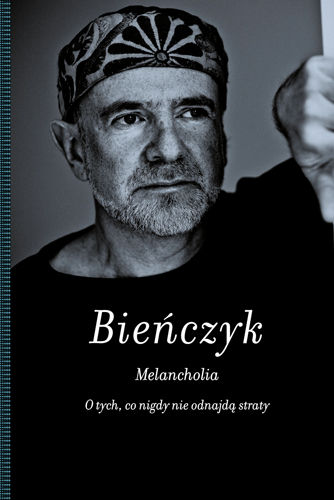

On a very adult note, Marek Bieńczyk’s Melancholia. O tych, co nigdy nie odnajdą straty (Melancholy. On those who will never regain the loss). A very short introduction to the topic. Erudite, yet approachable. The author’s also a novelist and wine critic. Teeming with references to melancholics past and present, their words and art. I can see it: tasteful dove-grey cover, November release date, Sebald fans raving about it.

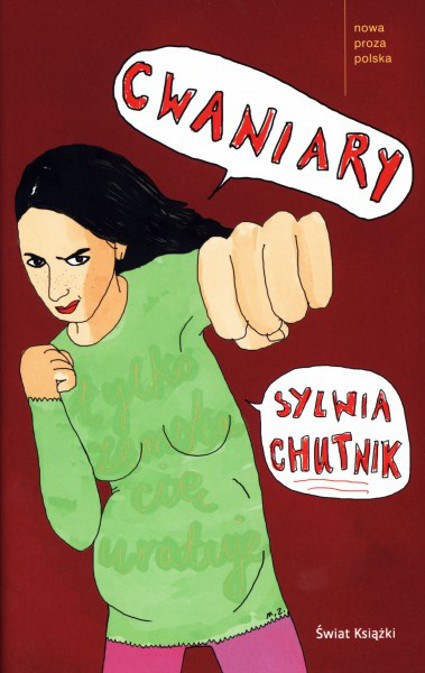

Sylwia Chutnik’s Cwaniary (Hustlerettes). It’s not a perfect book, but I can’t seem to shake it loose. The young author is an activist and DJ too. I call this one a feminist Fight Club combined with The Year of Magical Thinking. It’s about a gang of four friends, each of them working through trauma, all of them meting out justice. It’s a punchy, raw story about pain and grief, but there’s touches of Martahumour and tenderness too. When it hits you, it hits you hard.

Marta Dziurosz is an English-Polish-English literary translator, Translator in Residence at the Free Word Centre in London, and works at publisher Pan Macmillan. She is also an exhibiting photographer. @MartaDziurosz

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator from German, editor and musician. Her debut poetry collection Serious Justice is published by Test Centre. She is currently translating Dance on the Canal by Kerstin Hensel for Peirene Press. She is editor of Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt and acting editor of New Books in German. She is translator-in-residence at the Austrian Cultural Forum London. She plays in Sauna Youth, Monotony, Feature and GOLD FOIL. @niewview