Eyebrows were raised in 1967 when abstract geometric artist and prankster François Morellet created four symbols in neon light tubes which said when translated: Nil. No. Ass. Cunt.

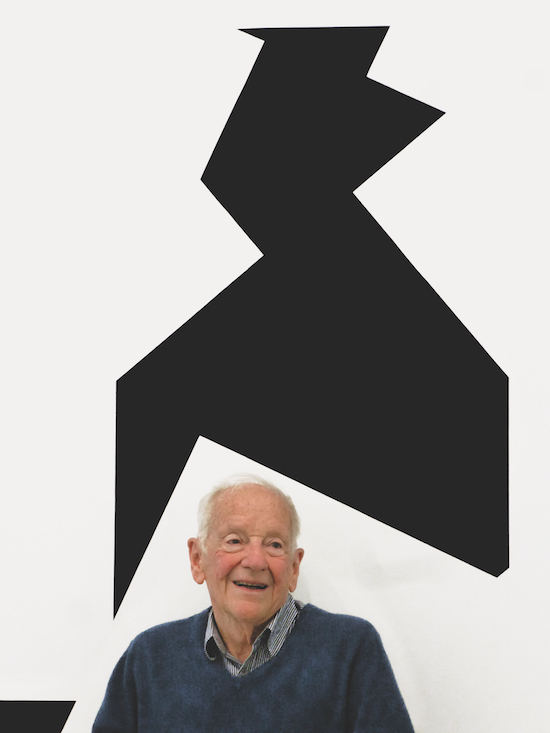

Now sixty years into a dazzling and varied career, it’s time to send your birthday wishes as two intriguing new exhibitions are unveiled in London to honour the French artist on his 90th birthday.

Born in the town of Cholet in 1926, Morellet is perhaps best known for his role as a founding member of the artists’ collective, Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV). Formed in 1961 with fellow artists such as Horatio Garcia-Rossi and Hugo DeMarco, he was instrumental in pioneering its playful and disorientating installations which demanded interaction from the viewer. But it is Morellet’s complex and beguiling geometric paintings and outlandish neon pieces that have secured his legacy as a master of minimalism.

Morellet discovered a love of the grid in the early 1950s from the uncompromising paintings of Piet Mondrian and has pursued his own sense of ruthless order and sly humour ever since. In the Sixties, he turned to his neon experiments to draw the line between industrial ready-mades and the luminous glow of modernity – including his seminal piece of artistic wordplay in Nil. No. Ass. Cunt. (or less amusingly titled: Neons avec programmation aleatoire-poetic-geometric) from 1967.

The larger of the two new shows is at the Annely Juda Fine Art gallery in Mayfair’s Dering Street. It’s packed with recent works, from glowing neon constructions (which arrived with hardly any instructions to assemble, a gallery assistant says with a shrug and a smile…) to bold large format paintings. Neither betrays the slightest sense of their maker’s hand – despite being full of joyous movement and an absurd sense of scale. These over-sized works offer plenty for the eye to feast upon while pushing the viewer to try to decode their inner grid references and humour.

Courtesy of Francois Morellet, Cholet

No one will ever know whether it was a moment of British prudence or just a logistical issue but the gallery kept perhaps the best piece of the show in the closet – Strip-teasing 4 fois no.10 – which depicts a racy blast of thick yellow shards intersecting with thinner black lines on a grey background. It’s a shame it didn’t make the cut and it is well worth hunting down in the gallery’s accompanying catalogue for a peek.

It’s Morellet’s inner joker that makes his consistently rigid if simultaneously hilarious work so appealing. He recently commented on his love of a good joke by saying: “Without humour, everything can become indigestible, in my work and in my life in general. If I had to speak seriously about humour, this could impair my own health.”

And yet, there is nothing more serious to Morellet than the process of making art. His dedication is effortlessly conveyed in the clinical methods and mathematical processes that he’s employed so effectively throughout his career, and his influence on American artists Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella should not be underestimated.

The second show is a short walk down New Bond Street and beams Morellet back in time to the early Seventies with 16 paintings on show at The Mayor Gallery. And it’s a journey worth taking. The works plot a direct line from Morellet’s studio in the post-industrial French town of Cholet to the collector Henri Chotteau, whose estate donated a large tranche of Morellet paintings to S.M.A.K. – the contemporary art museum in Ghent, Belgium.

To foot the tax bill arising from the Chottaeu bequest, the museum was required to sell other Morellet works. The paintings were acquired by James Mayor and now hang handsomely in his renowned Cork Street gallery.

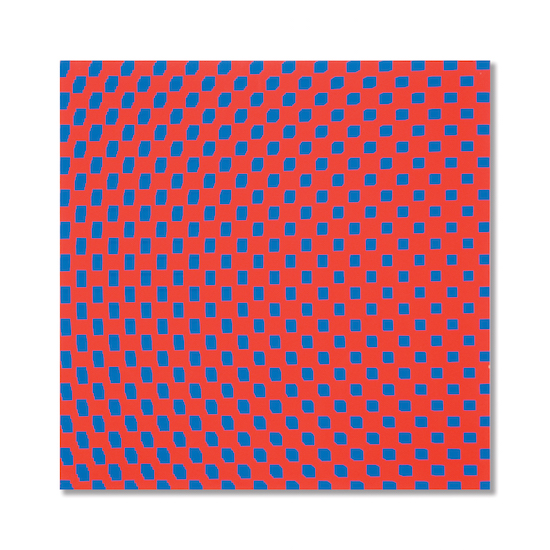

The bombastic showstoppers may hang in Annely Juda’s gallery, but the jewel in the optical art crown hangs in Mayor’s. Each of the paintings hold their own – whether it’s the dizzying 3 trames de carrés réguliers pivotées sur le côté with its overwhelming shifting red background and pivoted blue squares in the foreground or the deceptively simple black and white disrupted lines of 19 lignes parallèles et 21 lignes parallèles avec 1 interférence which looks like simple notebook paper that’s gone wrong. If nothing else, beware of the harrowing red background of 3 trames… it’s powerful enough to compel gallery manager Christine Hourdé to warn me from staring at it for too long.

Francois Morellet, 3 trames de carrés réguliers pivotées sur le côté, 1970

And unlike the works at the Annely Juda, the paintings at the Mayor exude a relative plethora of detail into the process of painting itself. Morellet’s hand is everywhere, even if it’s as steady as a metronome as he repetitively makes games out of depicting sets of lines that have been rotated by uniform degrees.

Of course, Morellet likes to make the simple difficult by creating a game in the process of choosing the degree of each line’s rotation. What number to choose? The numbers were often plucked randomly out of a phone book, I am told.

Or as Morellet describes it: “In order to channel my sensibility as an ‘artist’ I did away with composition, removed any interesting aspects of execution and rigorously applied simple, straightforward systems that could develop in a completely random way by means of participation.”

Courtesy of The Mayor Gallery, London

What he says is logical and erudite. But you can almost see the twinkle in his eye as he reveals the punchline. Together, contrasting tactics act like partners in crime to use and abuse chance with simple mathematical formulas, which in turn helps produce the kinetic grids and vertigo-inducing paintings that adorn the walls. They don’t shout, but quietly chuckle away until you notice. And once you start looking closer they suddenly appear to get both serenely, and deadly, serious.

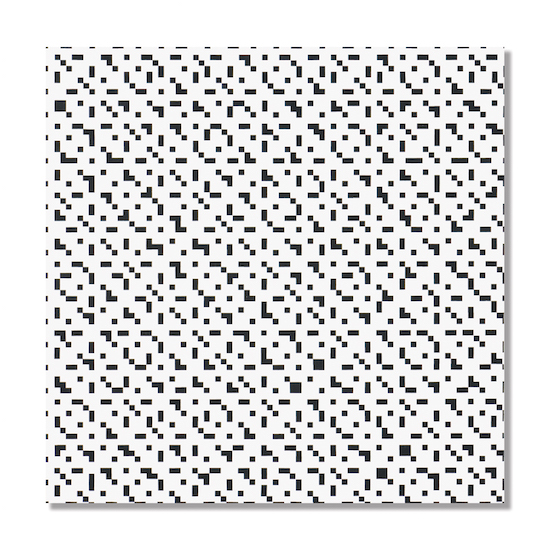

Meanwhile, Morellet unknowingly stumbled upon a startling digital reference with his 1974 painting on board titled Touse les 2-3-4-5 en diagonale. Dressed up like a hacked QR code its blocks and fragmented pixels dance a descending boogie woogie on the square board, offering an uncanny piece of geometric prescience in our overwhelmingly binary universe.

Francois Morellet, Tous les 2-3-4-5 en diagonal, 1974

The sister exhibition to these sixteen Morellet paintings completes a hat trick of shows of his work as they currently hang in the Dan Galeria in Sao Paulo. And while it’s taken 60 years for Morellet to get this kind of sustained and focused attention as one of the greatest living artists in the world, there can be no tiring of Morellet’s particular genius or his endless ability to make you reconsider time, space and irony.

Even if he just makes you feel wildly nauseous.

Francois Morellet runs at The Mayor Gallery until May 27 and Annely Juda Fine Art until July 9