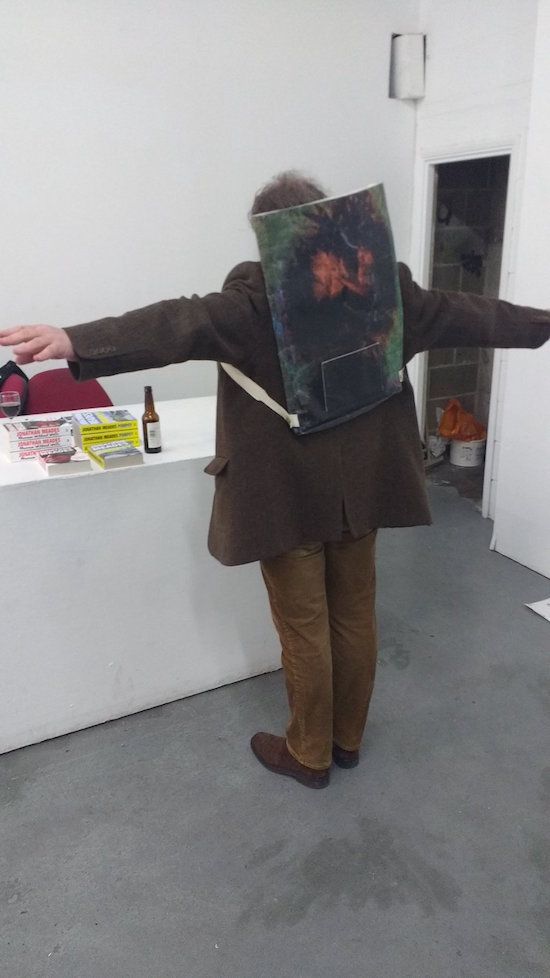

Jonathan Meades wears Jonathan Meades at an exhibition of work by Jonathan Meades. Jonathan Meades’s face, or at least the face of “Jonathan Meades”, the TV persona with black sunglasses who has performed barks to camera in an array of settings for over three decades, is depicted on the back of a bag he co-designed with Vivien Lee. He’s slipped it on, performing for some of those who have arrived early. Andrew Marr is on the guestlist for tonight, the publicity person tells me. So is Maxim from the Prodigy. The Londonewcastle space is set up, the bar stocked, books laid out at the counter, until the Meades sideshow is complete. Though his broadcasting and writing prompt you to believe the man is a master of all he touches, here you can’t escape the feeling that he’s a wheeler-dealer, a chancer, as the independent-minded British intellectual always must be. To have ideas above the agreed-upon and the banal, one is always in the process of getting away with it.

As it is, Meades is a mere visitor to the city he explored tirelessly for four decades. He has lived in an apartment in Le Cité Radieuse, Le Corbusier’s inspiration for Brutalism in Marseilles, for the past five years. When I arrive, he looks bemused to be hunkered down in a warehouse gallery on Redchurch Street, Shoreditch. Redchurch Street is the buffer where art meets moolah. Tim Noble and Sue Webster have a David Adjaye-designed studio around the corner. Property prices here have no doubt quadrupled in the past 15 years. Meades is horrified by what has happened to City-buoyed London outside our bunker, but not exactly surprised. He has long admired Ian Nairn, the scabrous critic who blew up in the 50s and 60s, sagged with drink in the 70s and died in the 80s soon after Meades’s unsuccessful attempt to coax him out of ale-imposed retirement. Watch Nairn on TV and you are presented with a fearful, fretful man, at times angry to the point of nervous breakdown. Meades’s durability and longevity are thanks to the fact that, while he shares Nairn’s disgust at the many idiocies power can inflict upon landscape, crucially, he stopped worrying – or rather, his constant sense of wonder at the ever-changing world around him overpowers any profound sense of horror before too long.

Today I feel more Nairn than Meades: shaky, in the grip of a cold that has taken most of my voice with it. I yelp questions rodent-like, a quiet scratch that gets lost in this large gallery space, as Meades directs me around his first visual exhibition, Ape Forgets Medication: Treyfs and Artnacks…

JM: Basically, when I do these things, and they are done by countless different methods, but the one thing I have in common is randomness. I do as much by chance, really as an antidote to writing, which I seem to be very precise and obsessive about accuracy and so on.

Do you go through many drafts when you’re writing?

JM: Yeah, but I’ll go through a draft of a couple of pages and if I get those right, move on. I don’t get to the end of something long and go about correcting it, I correct as I go. But the idea of this was an exercise in relaxation, but of course, once I started to become slightly obsessed by it, it becomes rather different. You tend to mitigate the randomness by the deliberate interventions and so on. The names of the pieces, in some cases, I look at the thing and it suggests something to me. Fons et origo, the name comes with it. One or two things are completely naturalistic. That for instance [we look at the work ‘A Bit Like Art’], nothing has been done to it. It was a photograph taken from a moving car in northern Scotland in very heavy snow. The trees very tight together. Ed, the guy from Coriander Studios who I give the stuff to – blows them up, that’s as far as his involvement goes, he doesn’t do any manipulation – looked at it and said it looks “a bit like art”, and so it’s called ‘A Bit Like Art’. I am using the most basic kind of digital camera [Jonathan pulls out a well-loved Sony camera the size of a credit card from his pocket]. I have a camera on my phone but I don’t know how to use it. Everything in this exhibition is done on this camera.

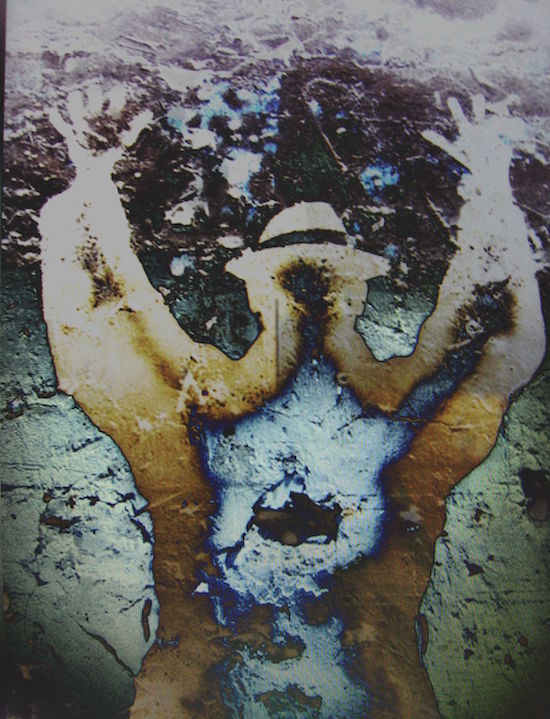

Jonathan Meades, Asterion Recalls Mother

There are endless techniques I use. I will photograph things and then change the colours. I will do paintings and froissage, which means paintings you crumple up. I paint with sponges, with various kinds of brushes, with squeegees, with rags and so on. I paint in my office at home. I’ve got a very big office. In terms of canvases I paint from A3, sometimes bigger. I use crayons, gouaches, acrylics occasionally. I rarely use oils as they’re too messy. I use crayons a lot and very soft 10b pencils. I really love extremely soft pencils, you can do so much with them.

When did you first paint? Was it at school?

JM: I did nothing at school. I just skived and kept my head down. I didn’t go to art school, I went to drama school – I don’t know why, because I’ve always had a minimal interest in the theatre but an extremely engaged interest in art. Not particularly in sculpture. Painting has always fascinated me. Music means very little to me, but painting, yes.

You knew Duggie Fields didn’t you. I wondered if the life of a painter ever tempted you back then

JM: I met him when I was at Rada and he was at Chelsea art school. No, I liked Duggie’s stuff very much but I didn’t [get tempted to try my hand at painting]. I felt very in awe of Duggie and a guy called Steve Walton, who I thought was a really great talent but Steve went into printing fabrics and so on, he lost interest in painting, which I think is a great shame. That group really interested me. Duggie’s stuff still. I have a great piece by Duggie, the Princess of Our Hearts, Diana looking up [Meades’ pupils raise coquettishly], the famous “There were three of us in this marriage” pose, looking completely loopy, catching that absolutely precise moment. But no, I wouldn’t have at that time dared to emulate what my contemporaries were doing. Whereas now I’ve got to an age where I don’t give a toss what people think.

Is there a refusal on your part to take making art seriously – it’s a happenstance activity compared to someone like Duggie, who has based his career on it.

JM: Well, I do take it seriously actually. I didn’t to start with, but I did this box of postcards called Pidgin Snaps. There are 100 postcards and 82 of them are realistic scenes, mostly of broken down caravans, transit vans in the middle of peat bogs, things like that which I like. There’s no trickery involved at all. It’s just what’s in the frame. But then about 20 of those things were abstractions from photographs of things like lichen, flint walls and so on, so you can’t necessarily know what the subject is, because if you look at a flint wall very close without any signal as to what the subject matter is, you don’t know. I kept getting bored with mundane subjects. I still do all the time, but I wanted to push it and go in that direction as a kind of abstraction without any kind of meaning and the meaning can be found afterwards. I’m not very interested in the meaning of these things, something is visually satisfying or it’s not. It’s as simple as that. If I could paint, I’d paint like Edward Burra or Otto Dix or Christian Schad or something, but I don’t have that kind of talent. But I discovered that I did have a certain aptitude for digitally manipulating things that I have made. There are several processes: drawing or painting, doing collage, and pushing on from there. It’s not just taking a photograph of something. I like layers of process which are revealed in layers within the work.

If I could pick out this work. Was this taken from a photograph to begin with?

Jonathan Meades, Adieu, Francis Le Belge

JM: I can’t actually remember how I did that one. Which is quite common for a lot of them. I don’t actually know how I got there. And if I did know, I would try and repeat it, but I genuinely don’t. It’s called ‘Adieu, Francis Le Belge’. Francis Le Belge was a well known Marseille gangster, whose name was something like Vanverberghe. No one in Marseille could pronounce it, even though his family had lived there for several generations, so he just became Francis Le Belge [Francis the Belgian]. Admirable record, he was first done for pimping at the age of 14, which I think is really going for it. He was eventually the top caïd in Marseilles and his life was constantly in danger, so he moved to Paris, and he made the terrible mistake of going to the same cafe each day, and someone came in and gave him some bullets for breakfast. Long after I had made the image, I thought of that.

But it’s kind of nonverbal most of this stuff. I don’t actually think about it in terms of what it looks like. I think about it in terms of shape, colours and layers. I like the slightly 3D quality that you can get with digital stuff. I’m kind of rather amazed that no one else does this. I’ve looked at a lot of digital art and there is a hell of a lot of kitsch, which seems to derive from video games and so on, Dungeons and Dragons… There are a couple of people in America doing this stuff but it is few and far between. I kind of liked the idea of doing abstract expressionism but not making a mess on the floor. I like the crispness and the cleanliness with this method. I’ve called it treyfs. I’ve seen about six different spellings of treyf, basically it means impure, not kosher. Something like maiale al latte, pork cooked in milk, is about as treyf as you can get. And artnacks is a pun on art and nack, a facility for doing something, which also suggests nicknacks, a completely worthless thing, and arnaque, which is the French word for scam or swindle, pulling a fast one. Not that I am pulling a fast one, but I like the idea of it. It’s my inner Arthur Daley.

What software do you use?

JM: Just the software that comes with the camera. That’s all I have got. As primitive as digital can be, there is nothing automatic in the methods I use, it’s all basically done by hand. I know nothing about computers. I don’t like computers. I use them for writing because I have to. I have never had a conversation about computers in my life.

And with your internet presence, it’s there because somebody else has built it. Meades Shrine for example

JM: We still don’t know who he is, but I am very grateful that he has put out my stuff, because the wretched BBC never would.

What do the wretched BBC think of Meades Shrine?

JM: I’ve no idea. I don’t give a toss what anyone thinks there, apart from people like Frank Hanly my director, and Anthony Wall, but the BBC executives are just absolute arseholes.

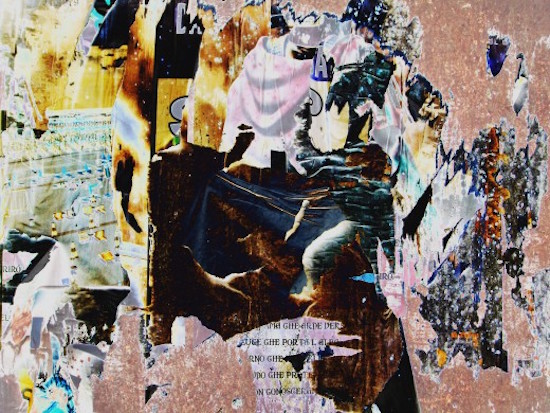

Jonathan Meades, Babsk: 03/09/89

This is several layers of collage, including collages of posters which have been stuck on top of each other and ripped off. It is called ‘Babsk: 03/09/89’. I was working in Rome in 1990, just after the World Cup. I was talking to this cinematographer, waiting for a taxi, kind of leaning against a wall with loads of torn posters. We were talking about football and I mentioned an Italian footballer called Gaetano Scirea, and he said did you know he was dead. He was killed just after he retired, in a car crash in Poland while scouting for Juventus. He was libero, a defender of the quality of Bobby Moore. He didn’t really have to tackle because he got there first. His timing was wonderful, he never got a yellow card in his life. The most immaculate player. I was pretty shocked. He wouldn’t have been playing the ’90 World Cup but he was in the ’82 World Cup winning team and he was in the ’86 team

We arrive at the modest bar built into the wall that divides two of the gallery rooms, and lean against it.

JM: Do you want a glass of wine?

Erm. Do you think it would be good for the voice? I’ve got a fear of completely losing it, but maybe it might lubricate it.

JM: Go on go on. Come on, let’s do it. Cheers.

How much of your life does the art take up?

JM: Not much. I probably write for about six hours a day, but do this for an half and hour, an hour. Writing is much, much harder work than this.

When you say writing…

JM: TV, journalism, fiction; I’m always writing something. I tend to have three projects on the go at the same time.

It is quite interesting that in recent years you have branched out. You hadn’t really done anything like this show before and before that you made the record with Mordant Music. You are ambling in new territories, and I wondered if that spoke to a keenness to experiment with other forms.

JM: Well, Mordant Music came about because Chris Petit had done a record with them, and Chris suggested they ought to get me to do one, but it was not my initiative. This is different because when I started doing this stuff I had no thoughts of an exhibition but after Pidgin Snaps, it kind of spurred me to go further. I had to work out how it could be exhibited and so on, I had no idea and talked to various painters, all of whom said avoid fucking galleries because they take 70 per cent. I remember years ago, my friend Glynn Boyd Harte who has been dead for many years, was shocked when a gallery moved from 40 per cent to 50 per cent.

What’s the deal with this gallery?

JM: This gallery you have to show your work and they decide whether they want you to let have the gallery. It comes free but you have to supply the drink, security etc. They are property developers but they have a social conscience. They’ve got this space and they think it should be used rather than let it sit here.

This is a growing trend: property developers funding more discursive art exhibitions and publications, such as the new architectural journal White Noise, which is based in White City and is funded by the property developer, Stanhope. Is there a conflict at all?

JM: I think there is a conflict in all writing that is sponsored, by farmers, the oil industry etc. I worked very briefly from the autumn of ’79 to the spring of ’80, six months until I got sacked, for Architectural Press, which produced Architects Journal and Architectural Review. Basically, you had to be on the side of architects about everything. I wasn’t, so they gave me the push. Fair enough. They have to sell to architects. There is always going to be a conflict if you have got someone who doesn’t agree with the premise that architects are the most wonderful people in the world. I think if property developers are funding things, it does compromise you a bit, but a world without compromise doesn’t exist. It’s the way of the world.

For some reason it feels more natural for visual art to be sponsored, over writing.

This work is not making any point. I am not interested in making points, for the most part, in a lot of writing. I think the notion that the writer is someone with nothing to say is quite good. If you decide ‘Murder is a bad idea’ and you write a thing which shows that murder is a bad idea, what’s the point? It’s much better to not know what you’re saying. James Joyce said: ‘Don’t think, start writing.’ The trouble with James Joyce, he took too long to write anything. Anthony Burgess did the same, he had various strategies for writing which were quite extraordinary. He would open up a dictionary and use the first half a dozen words he found. There is a particular instance where he has decided to describe a hotel lobby and used one page of an English-Malay dictionary, because you would get English words which no one would usually think of in the context of a hotel lobby. Which is nothing to do with making a point. It’s a purely literary device, which has nothing to do with didacticism or having an opinion, it’s a form of creation.

You are seen as an outsider because of this, the fact you don’t just hammer home one point. Is that difficult, or has it worked in your favour as it has carved out a niche?

JM: I have tended to not fit in, but it’s not a deliberate ploy to be an outsider at all. It’s something to do with my mentation and the way I think and so on. I haven’t made a deliberate policy to try and move into a particular direction. I mean, the next book that comes out is a cookbook called The Plagiarist in the Kitchen, which is basically devoted to the idea that you shouldn’t try and invent anything in the kitchen and just rely what has already been done and fuck Heston Blumenthal. I hate the idea of experimental cookery, but I like the idea of experimental literature. I think the novel should be novel, rather than this institutionalised form which has developed, within which very few people seem prepared to break the mould.

Cookery, in terms of its public perception, has moved into this sphere that art might usually have held, whereas the popular novel has become this sacred country walk.

JM: Yeah, it has. Obviously there are exceptions. Someone like David Mitchell is really rather special, and there’s a French writer who interests me a lot called Régis Jauffret who is really quite something, much more interesting than Houellebecq, for instance. He kind of reminds you of what writing can actually do.

Meades’s attention is caught by the bartender. She puts a box of craft beer down and explains the selection to him, recommending a 6% ale, brewed in London.

JM: Why don’t we try some of that, I’m afraid I don’t terribly like the wine. But I don’t terribly like red wine in general. I prefer white. But my taste has changed, as no one in Marseilles drinks red wine you never see anyone drinking it. They drink rose with ice in it, because it is such a hot place. Marseilles is not France. It is to France what Liverpool is to England.

When did you move to Marseilles?

JM: Five years ago. We lived in the French countryside about four years before that and before that we lived in Bermondsey street, which is now turned into a southern Shoreditch.

Do you still have a place here?

JM: I don’t. I very foolishly didn’t buy one before we went. We could move back if we sold up in France. I once had two places at the same time: I inherited my parents’ house. I found having two places to look after, you have to be so bloody organised, and you have to visit all the time. It was a shit house but in a beautiful place, right beside the meadows, where two rivers joined up, looking straight over at the cathedral and so on. Constable had actually painted from what became the bottom of my parents garden. I thought I’d get the house refurbished so I got my friend, the big-time architect Piers Gough, to come and have a look at it. He said: ‘I know exactly what we need to do.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Pull it down.’ I couldn’t afford to, so I sold it. But having two homes, you need money and more than that you need organisation. I stay in hotels when in I’m in London, which I like.

When you come back to London, do you wonder what’s happening to it? We are in the epicentre of the change here.

JM: I mean, here, it’s like a Martian arriving. It’s very, very different, a lot of it in a really terrible way. Awful, terrible commercial architecture all over the place. People who were extremely good architects like Rogers, Foster etc frittering away their reputations doing stuff for the Candy brothers, who ought really to be in prison. I don’t understand why they do it, the world’s leading architects trying to prove they can produce shit like everyone else.

Which buildings in particular are we talking about?

JM: A huge amount of stuff in the City: the Cheese grater, the Gherkin, the Walkie-Talkie, the Dildo. So much is so bad. Coming into London from the east, from the Dartford Bridge, you see all these towers coming up and you think, ‘It’s a bit like Dubai.’ And then you get a bit closer and you think, ‘Well it’s actually not like Dubai, it’s like a moderate town in the Midwest, like Minneapolis, Denver or St Louis or somewhere.’ It’s kind of pathetic. Either you have a city of towers or you have a low-rise city. The two don’t go together at all, I think. So much of London looks a real mess. Also, it’s a permanent building site. They drool on about sustainability, but the most unsustainable thing you can do is to build a building. It’s wasteful of energy, it fucks up the lives of people all around it. Where we lived in Bermondsey Street was just near the Shard. You build the Shard and the effect of the Shard goes on for hundreds of metres: lorries, nowhere to park, a huge new influx of people working there. The social cost of new buildings is extraordinary. And at the same time, you’ve got tens of thousands of empty buildings in London, which a dirigiste government would just compulsory purchase for the homeless. It’s ghastly, the homelessness here. Very occasionally you notice someone sleeping on the street in Marseilles. You do in Paris, but London leads in homeless, and it’s shameful. Nothing seems to be done about it because the market is the God. You worship mammon, that’s it. I think it’s very uncivilised.

London is such a special case isn’t it – this kind of business-first architecture that does nothing for the people. Is there anything comparable in France?

JM: No. France has always had much more authoritarian governments. But what did happen in France during the early years of Mitterrand is there was a huge decentralisation, which gave power to local governments and so on. The mayors of small communes have the power to grant planning permission. Because the mayor’s stipend depended on the number of people in their commune, they were tempted to encourage building so that more people would move in and their stipend would go up. The result of this is you’ve got really hideous bungalows being built in fields which have previously been devoted to wheat or corn for hundreds of years. These awful bungalows were put up and look exactly the same wherever you go, except in Provence they’re pink, elsewhere they are biscuity colour and in the Basque country they have plastic beams attached to them. It’s really very ugly. For the most part, French cities are much better preserved and looked after than British cities, because the bourgeoisie, the people who run the cities, have always lived centrally, which has only recently begun to happen in big cities in England. Traditionally in England, people who had any money would live out in the suburbs. Now, increasingly, people with money live in the cities, but this has changed only in the last 20 or so years. We saw this when we lived in Bermondsey Street, people who would have traditionally commuted from Beckenham or Pinner or somewhere into the City realised that if they lived round Bermondsey Street they could walk to work, rather than hang around for a train that never arrives. These people with bonuses and enormous salaries can live a completely different life than they would have lived in Chislehurst or Richmond. But people with no money will still have to commute, and are pushed further and further out.

All the while council tenants from the outskirts of London are being rehoused in the north.

JM: All this northern powerhouse thing is ridiculous, because it is centred around Manchester. Manchester is actually closer to Bristol than it is to Newcastle, and is getting huge amounts of money, whereas Newcastle, Sunderland, Gateshead etc, who really need it, are not. Nor are the Yorkshire towns. Places like … I don’t know if you saw Happy Valley?

I did. Did you enjoy it?

JM: Yeah, to an extent. It was perfectly all right. It just went on a bit, like everything does. I wish they’d bring back the single play, 90 minutes, just like a feature film. Fabulous. But they don’t, they all drag on and on. Breaking Bad, great, but it’s just the same thing – you know, Jessie gets bolshie or something – every week. The only one I really like is Lilyhammer. It’s sensational. Steven Van Zandt is quite something. He’s Bruce Springsteen’s guitarist and just extraordinary as an actor. It was so funny. That’s the problem with most of them, they take themselves so seriously. This took itself seriously, but the idea that humour isn’t serious is preposterous. You look at some of the great humourists, like Flann O’Brien. Joyce is very funny, Nabakov is very funny…

The photographer comes over. He shoots Meades, and various works. They go on to talk about the equipment the photographer is using, in particular the digital cartridge, which hasn’t changed in size for years.

Photographer: … You wouldn’t want a tiny one.

JM: There seems to be this techie occupation with miniaturisation. Imagine if they got a preoccupation with introducing maglev trains or something.

We seem to be at the behest of technology, Silicon Valley dictating ‘progress’, making things smaller and smaller so that people can communicate more and more frequently. Do you have any interest in tech, such as the new iPhone?

JM: I have a five-year-old HTC phone. I’ve just written a piece for the Guardian about this. I don’t know about virtual world, I think it’s more a kind of parallel world. I think the advantages and disadvantages of technology are hugely exaggerated. It doesn’t make that much difference. Sure if you’ve got a mobile phone, you use that over your landline. But I think that life goes on and we absorb stuff. In a few years, people won’t be taking selfies – or if you’re Ashley Cole, ‘groinies’.

You are into football aren’t you? Which team do you support?

JM: Southampton. They’re OK at the moment.

Are you looking forward to France welcoming Roy’s boys in Euro 2016?

JM: If they play the right team, they could be good. So long as Woy steers clear of Rooney and the carthorse Milner they have a slight chance.

Could I get your England first eleven?

JM:

Fraser Forster

Nathaniel Clyne, Chris Smalling, Luke Shaw (if fit, otherwise Danny Rose)

Danny Drinkwater

Ross Barkley, Jonjo Shelvey, Adam Lallana

Dele Alli

Harry Kane, Jamie Vardy

APE FORGETS MEDICATION: Treyfs and Artknacks runs April 7-23, 12.00 – 19.00 ( including Sundays) at Londonewcastle Project, 28 Redchurch Street, London E2 7DP

Londonewcastle Project, 28 Redchurch Street, London E2 7DP.