The Anacostia River in Washington DC is one of the most abused stretches of water on the planet. This nine-mile tributary of the Potomac has, from the founding of the American capital in 1790, born the brunt of a rising nation’s hyper-pollution. Raw sewage was dumped freely for decades, augmented by industrial run-off from the Washington Navy Yard – a facility so environmentally hazardous it was in 1998 designated an emergency zone by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Stepping along the banks on a muggy DC summer, it can feel you’re following the Anacostia all the way to hell.

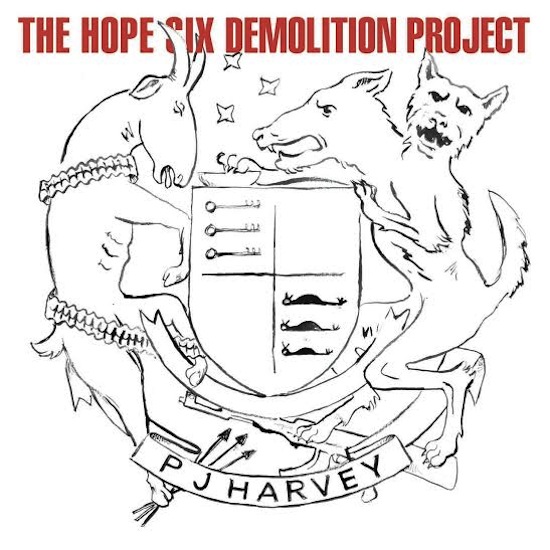

Whether Polly Jean Harvey walked this same twisting route when she visited Washington with war photographer Seamus Murphy in 2014 is not recorded. We do know the Anacostia and the many degradations heaped upon it left an imprint. Harvey recounts these environmental depravations on ‘River Anacostia’, an eerie hymnal shimmering into focus at the mid-point of her ninth album, The Six Hope Demolition Project.

"Walking on the water/ flowing with the poisons/ from the naval yards," she enunciates, her upbeat coo contrasting with the grave subject matter. Harvey is not here to affix blame or offer easy answers. She is merely gazing out at this sad, ravaged water-way, wishing things had worked out other than the way they had.

So it goes throughout The Hope Six Demolition Project. The album has in certain quarters been hailed as a doubling down on the geo-political truth-telling of 2011’s Mercury-winning fever-dream Let England Shake. In terms of textures and arrangements, the two unquestionably flow from the same wellspring. Harvey again builds her songs from chiming guitar and thunking percussion while reprising the sugar-spun howl that was a forceful aspect of the earlier record.

Beneath the surface matters are more complicated. The new collection was inspired by field trips to Washington DC, Kosovo and Afghanistan in the company of Murphy (with whom she in 2015 published a volume of poetry and photography, The Hollow Of The Hand). Yet Harvey did not return with a concise message. Where Let England Shake could be read as more-or-less straightforward protest against British military intervention in Iraq, here the takeaway is of a different order of nuance. The album is insistently digressive, political only so far as it chronicles a sequence of engagements with comparatively obscure pockets of humanity. At no point are we told how we should feel. Harvey bears witness, never preaches.

There has been a backlash, of sorts. Residents of DC’s historically disadvantaged Seventh Ward are reportedly aghast at opening track ‘Community Of Hope’ and its depiction of their neighbourhood as meth-ravaged purgatory. The Washington Post reporter who gave Harvey and Murphy a guided tour by car of the city’s rougher backstreets has meanwhile expressed surprise that a throwaway line of his – "they’re gonna put a Walmart here" – would be repurposed as the song’s mantra-chorus. And it’s true that Harvey does not hold back. She sings of the "highway path of death and destruction" and a school that "looks like a shit-hole", her observations couched in one of those pummelling melodies that have been her trade-mark going back to 1992 and her debut Dry.

Delving into the record, I was reminded of a recent documentary about Somalian pirates by long-time Richard Linklater collaborator Tommy Pallotta. As with Harvey, Pallotta is determined to contextualise a complex story outside the narrow parameters of political invective. In Last Hijack the central figure of hijacker Mohammad is portrayed on screen as an animated eagle fluttering high above the ocean, a surprisingly devastating metaphor for the freedom and hope piracy represents for the impoverished ex-fisherman. The film doesn’t take a position on piracy – merely invites us to consider why it might prove attractive from the perspective of a Somali worried where his next meal will come from.

"Every year a list is published of the year’s most under reported stories," Pallotta told me last year." We never heard anything from the perspective of the pirates in Somalia – I was reading a lot of things about illegal fishing and I wondered why people would go to such extremes. You see these guys in pretty small fishing boats taking on these giant cargo ships. It struck me as a story of simple survival – what would any of us do, in those circumstances?"

In her way, Harvey is wending a similarly peripatetic trajectory. The sensory tumult of DC, Afghanistan and Kosovo infuse The Six Hope Demolition Project but she keeps her thoughts off the page. This is documentary in its purist sense. There are no value judgements – just an act of bearing witness (even if the "facts" are often mired in mystery – when she sings of the "28,000" children vanished in ‘The Wheel’, the context is unclear, even if the message is haunting).

A further layer of ambivalence was added by the unconventional circumstances in which the LP was put together. Harvey, working with producer Flood and John Parish, assembled the album at Somerset House where members of the public were invited to watch her record in 45-minute sessions (the instillation titled ‘Recording In Progress’). She is said to have found the experience initially challenging, until a one way mirror was installed so that, while Harvey knew she was under observation, she could not see the people gawping and pointing.

The framing gave Harvey license to breach the four walls of her own perspectives and scrutinise her music as if from afar. The songs are intricate and embellished, employing the same palette of wailing riffs and chanted vocals that have been a feature of much of her post-2000s output. But they never chase their own tails or fully inhabit a reality of their own creation. Indeed, it is appropriate that Harvey was accompanied on her field studies by a photographer because the The Hope Six Demolition Project has the quality of a gallery exhibition. "The boy stares through the glass/ he’s saying dollar dollar/ Three lines of traffic past/ we’re trapped inside our car," Harvey sings on ‘Dollar Dollar’, one of several tracks strip-lit with photorealistic imagery. It’s hardly ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’, and perhaps that’s the point.

Harvey went out into the world and here reports her encounters in abrasively straightforward fashion. Some might deem the lack of personal perspective an oversight. Yet in keeping herself at one remove, Harvey lets the inner truth of her experiences shine more brightly. To spend time with this record is to peer over her shoulder as she casts aside the familiar and embraces the strange and unknowable. It is, by those standards, an exhilarating affair – a political album whose most daring gesture is its refusal to evangelise or furnish easy comforts.