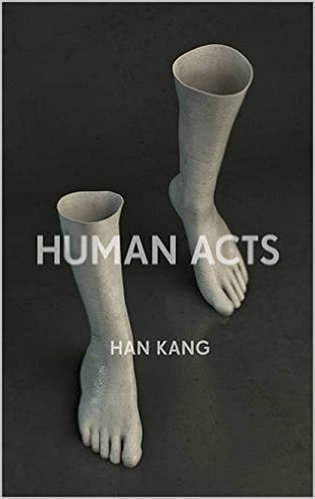

A few weeks ago I went to Foyles Bookshop in London to see an appearance by Korean author Han Kang, mainly because there had been something around her that doesn’t usually happen to a non-European author in translation: excitement. Here we all were, in a large, packed out room, for a Korean writer. Kang’s second book in translation, Human Acts, had just come out with Portobello Books, following on from its ‘sister’, The Vegetarian.

When she started speaking (an interpreter was present, but Kang only asked her to translate one term in the course of the evening) her voice was incredibly quiet, the softest of speaking voices, practically non-existent even through a microphone. Everyone shuffled around, worried that they wouldn’t be able to hear. But then we adjusted. The room shifted from silence, to an absolute void where Kang’s voice was the only sound, as if whispered to each person individually. It’s a voice that commands your attention because you must listen carefully. It’s a voice that will not be raised. When she read an extract of her book, Korean sounded like nothing I’ve ever heard before; it was rolling and smooth, I couldn’t decipher a rhythm, only brief pauses. I never knew where one word ended and another began, it was simply warm, textured sound.

Human Acts explores the student uprising and massacre of 1980 where around 600 people are estimated to have been killed protesting the government in the South Korean city of Gwangju. Kang was born in the city in 1970 and lived there until she was around 9 or 10 before moving with her family to Seoul, closely missing the atrocity itself. She later ‘discovered’ it on seeing a photographic record of the massacre and the ‘riddle’ of the book was what she needed to solve through Human Acts, motivated by what she calls a form of ‘survivor guilt’.

Two questions posed themselves:

How could people commit such extreme violence?

How could people challenge such extreme violence?

Researching and writing the book, Kang explained, took her to the edges of losing faith in mankind: “I almost gave up”. But she had to write it. The memory of what had happened had been fading from the very moment it had happened; it hadn’t been acknowledged and no information had been released until 1997 – seventeen years after the fact – and it hadn’t really been written about in literature since the turn of the millennium. The truth was getting mangled in different ‘official versions’ and a single textbook is currently being written by the democratic regime. Even more disturbing for Kang was that children of school age didn’t know anything about it. She felt it was larger than her, that she “wasn’t important anymore”: “I wanted to lend my sensations, my life, to the people killed”.

The book was a grieving process where she needed to “mourn as much as possible,” but it was ultimately a transformative experience where Kang’s energies and focus “went from human violence to human dignity”, to the “second question”: those who fought, those who died, those who survived, those motivated by love.

At the end of the night, the applause was so loud that it got picked up by the microphones and came splashing over everyone through the PA, wave after wave. I had The Vegetarian and Human Acts waiting for me at home and I read them both in a matter of days.

The Vegetarian doesn’t get you from the first page, but the first line. I’ve had messages from people I’ve recommended it to after about page two.

The vegetarian is a woman trying to disappear, trying not to hurt anyone, withdrawing completely from life and from her human form. We watch as she becomes weaker and more detached – and yet become aware of herself, in control, empowered through the ownership of her destiny. Those close to her who fail her – by being disturbed by the disruption of the status quo, by prioritising their own desires, or by hiding from a truth that’s been there all along – are explored in such a way that you cannot possibly resent them. You empathise with them because they are human.

If The Vegetarian’s visceral depictions of the human body may, at its most extreme moments, alienate the reader from the burden of their own body, Human Acts will bond you with a succession of decomposing corpses. The book gives voices to the dead, the tortured, the abandoned, the forgotten. You mourn the scores of murdered student protesters – unclaimed – as much as the censored play script, returned having been all but voided. What lingers is the thought that such a massacre is only starting to re-enter public consciousness – this book’s contribution cannot be understated – having been forcibly, and violently, forgotten. That Kang wrote this book because of and in spite of her unshakable fear of not being able to ‘embrace’ humankind while incorporating this deafening silence makes the work all the more necessary and miraculous.

I’m going to get to the point: read as much of and about Han Kang as you can. Read Human Acts, read The Vegetarian. Read this short story, a pre-cursor to The Vegetarian in Granta. Read this interview with Han Kang in The White Review. But when you’re reading all these words by Han Kang, remember that you have the privilege of reading them because of Deborah Smith. It’s all a double privilege: to read Han Kang, and to read Deborah Smith.

I’ve heard Smith speak at a number of events and been fascinated by the unique challenge and her personal experience of translating Korean into English – the order of disclosure within a chapter having to flip, how ‘we’ and ‘I’ blends in Korean, how she has stayed true to Yorkshire in her word choices – and there will be moments where you will read the addictive prose of these stories, suddenly pause and think: how did she do this?

At the end of January, Smith was awarded an Arts Foundation Award, a grant of £10,000, which was presented by Sebastian Faulks (there’s a great photo of them together with Smith’s cheeks puffed out in elated shock and Faulks giving her a pat on the shoulder). The award was in recognition of her outstanding translation and publishing work – past, present and future – and she’s planning to use her grant to research and translate Yi Chong-jun, widely regarded as Korea’s most famous and prolific author.

Smith’s dedication to the Korean language and culture, her incredible skill as a literary translator (Deborah Levy rightly described her as being ‘obviously a genius’), her visibility as a speaker and her motivation to change the literary landscape by founding Tilted Axis Press – a publishing house dedicated to authors from Asia from an intersectional feminist standpoint – are remarkable. She managed to answer my questions just before she flew to Japan for Tokyo International Literary Festival, with plans of translating Han Kang’s next book on the flight (though she said the trip was meant to be kind of a holiday).

What did you study and when did you begin learning Korean?

Deborah Smith: I did my BA in English lit, and hated the restriction – I’d always read more in translation than not; coming from a working-class background, what I knew of as British literature – the writers who made big prize lists and/or were stocked in WH Smith, Doncaster’s only bookshop until I was 17 – seemed incredibly, alienatingly middle-class. Then in 2009, just after the financial crash, I graduated with no more specific skill than ‘can analyse a bit of poetry’.

I suspected learning a language would be both useful and enjoyable (I love memorising lists of things), and would get rid of the embarrassment of being monolingual at 21. I’d been obsessed with reading for as long as I could remember, the only thing I’d ever thought I might want to be was a writer, but I was much better at crafting sentences than at stringing plots together. All of which suggested literary translation, and Korean seemed a good bet – barely anything available in English, yet it was a modern, developed country, so the work had to be out there, plus the rarity would make it both easier to secure a student grant and more of a niche when it came to work. So I taught myself the first year course while I was on the dole, then moved to London to do an MA at SOAS, which led straight into a PhD. Finally submitted last September!

You’re often described as the only literary translator of Korean into English. Are you really in such an isolated position? Is there a growing community of Korean to English translators?

DS: Actually, I’m frequently described as the UK’s only translator of Korean literature, but even that isn’t accurate – Agnita Tennant is UK-based, Janet Poole is British though lives in Toronto, Brother Anthony was born here though is now a naturalised Korean citizen. There’s also Chi-young Kim and Sora Kim-Russell, who are younger and do fiction for commercial houses.

I teach Korean translation at the British Centre for Literary Translation summer school, so I see an emerging generation too, who are around my age. I’m hoping to find time to mentor, and to help emerging translators to a first contract through Tilted Axis.

How is it that you came to translate Han Kang? What’s your relationship with her like?

DS: I read The Vegetarian and fell in love with it. A year later, I was invited to go and speak at the London Book Fair (which I’d never even heard of before), as they were gearing up for Korea being the market focus country in 2014. I met Max Porter there, Kang’s editor at Portobello, sent him my sample, and the rest is history.

Possibly the best thing about the whole experience is that Kang and I are now really good friends. It’s as much of a pleasure and privilege to know her as a person as it is to translate her work. She’s been over for two UK publicity tours, which means lots of time to chat on trains etc., and she was hear all last summer for a writer’s residency in Norwich, where I got to meet her son too.

Whenever I visit Korea she buys me lunch and takes me to a gallery. As if all this wasn’t enough, she has incredible respect for translation as a creative, artistic practice – she insists that each English version is ‘our book’, offered to share her fees with me when she found out I wasn’t getting paid for translating her publicity stuff, always asks the editor to credit me, and does so herself whenever she’s interviewed. Too good to be true.

What are your next translation projects?

DS: Alongside Han Kang, there’s only one other author I’ve chosen to translate so far – Bae Suah. Her work is radical both stylistically and politically, influenced by her own translation practice (she’s translated the likes of Kafka, Pessoa, and Sadeq Hedayat into Korean). Her language is simply extraordinary. I first came across her when I read some elderly male critic castigating her for ‘doing violence to the Korean language’, which of course was catnip to me, especially as I’d recently discovered Lispector doing pretty much the same to Portuguese.

I’ve translated two of Bae’s novels, A Greater Music and Recitation, which are coming from Open Letter and Deep Vellum in October and January respectively. A Greater Music is a semi-autobiographical book centred on a Korean writer moving to Berlin, learning to live and even write in a foreign language. There’s no linear narrative – the structure is more like a series of variations on a theme (how identity is shaped by language), with the past constantly bleeding into the present, dreams into reality. And the language, while incredibly lyrical in places, also has this underlying dissonance, the sense of it having itself been translated. But there’s also a strong emotional core to counterbalance the experimentalism, with some incredibly moving passages around the narrator’s relationship with her (also female) German teacher. It’s beautiful.

When did you start thinking of founding Tilted Axis and what pushed it into a reality?

DS: I was in the second year of my PhD when I first had the idea – I’d recently started working as a translator, which meant firstly that I was hearing about amazing-sounding books from other translators, and also that I was getting enough of an insider’s view of the publishing industry to be aware of all the implicit biases that made it so difficult for these books to ever get published, especially if they weren’t from European languages (harder to discover, editors can’t read the original, lack of funding programmes, authors who don’t speak English). Plus, publishing’s inherent conservatism, means that what little did get through was weighted towards the commercial end of the scale, which is not the kind of writing that excites me.

This and the small sample size inevitably leads to stereotypes – sweeping family sagas from India, ‘lush’ colonial romances from South-East Asia. Mother and daughter reconciling generational differences through preparing a ‘traditional’ meal together. Geishas. And even if something more exciting does manage to sneak through, it gets the same insultingly clichéd cover slapped on it anyway, so no one will ever know.

So the aim for the press was a mixture of things: to publish under-represented writing, which is an intersection of original language, style, content, and often its author’s gender. To publish it properly, in a way that makes it clear that this is art, not anthropology. To spotlight the importance of translation in making cultures less dully homogenous. And to improve access to the UK publishing industry – I’m hoping to set up an internship or work experience for someone from a low-income background, as soon as we have the funds. While we don’t have the funds, we won’t have an intern. Not only are unpaid internships exploitative, they’re one of the main forces keeping publishing in this country a primary white middle-class industry, which has a direct knock-on effect on what gets published and how.

What pushed it into a reality was securing a start-up grant from Arts Council England. God bless them.

Who is involved with Tilted Axis?

DS: Simon Collinson, of digital publisher Canelo and über-cool Aussie mag The Lifted Brow, is our digital producer; Sarah Shin, Verso’s comms director, is helping us out with press publicity; Soraya Gilanni, who mainly does production and set design for films and commercials, is our art director.

Who will you be publishing first and in the near future?

DS: Our first-year list is Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay (translated by Arunava Sinha), Hwang Jung-eun (translated by Jung Yewon), and Khairani Barokka.

Sangeeta is a stylistically daring writer in love with surrealism, credited with being ‘the woman who reintroduced hardcore sexuality to Bengali literature’. But though the (male) establishment used this label of erotica to dismiss her work, the sex scenes have exactly the same transgressive function as her use of chronology and narrative voice.

Hwang Jung-eun is one of the brightest stars of the new South Korean generation – she’s Han Kang’s favourite, and the novel we’re publishing scooped the prestigious Bookseller’s Award, for critically-acclaimed fiction that also has a wide popular appeal. She stands out for her focus on social minorities – her protagonists are slum inhabitants, trans women, orphans – and for the way she melds this hard-edged social critique with obliquely fantastical elements and offbeat dialogue.

Khairani Barokka is a writer, spoken-word poet, visual artist and performer whose work has a strong vein of activism, particularly around disability, but also how this intersects with, for example, issues of gender – she’s campaigned for reproductive rights in her native Indonesian, and is currently studying for a PhD in disability and visual cultures at Goldsmiths. She’s written a feminist, environmentalist, anti-colonialist narrative poem, with tactile artwork and a Braille translation. How could I not publish that?

Tilted Axis Press launches on Monday 11th April at the Free Word Centre and Deborah Smith will be taking part in a panel on literature and diversity on Thursday 10th March, also at the Free Word Centre.

Deborah Smith‘s translations from the Korean include two novels by Han Kang, The Vegetarian and Human Acts (both Portobello UK, Crown US), and two by Bae Suah, A Greater Music (Open Letter 2016) and Recitation (Deep Vellum 2017). In 2016 she won the Arts Foundation Award for Literary Translation. Deborah is publisher and editor at Tilted Axis Press, which she founded in 2015 while finishing a PhD in contemporary Korean literature at SOAS. She tweets as @londonkoreanist.

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator from German, editor and musician. Her debut poetry collection Serious Justice is published by Test Centre in March 2016. Her most recent translation is Nicotine by Gregor Hens, published by Fitzcarraldo Editions. She is editor of Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt and acting editor of New Books in German. She is translator in residence at the Austrian Cultural Forum London. She plays in Sauna Youth, Monotony, Feature and GOLD FOIL. @niewview