A landscape that becomes a painting, then a page in a book, is doubled further to become once more an image for display, a panorama, and a terrain. A museum vitrine becomes a screen, only to be enclosed within another screen, and re-displayed, as in a museum. The work of Alexandra Leykauf is full of such foldings and parallaxes. Reality warps and wrinkles, our perspective flattens and then pops out again. Always the trace of each step of the process remains, as if our brain were able to freeze time at the very moment our eyes were fooled or suddenly made cognisant.

Born in Nuremberg, a graduate of the city’s Academy for Fine Arts, I first met Leykauf in Sérignan, in the south of France, two years ago. Her works were included in a group show at the Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain there, alongside things by Peter Downsborough and Gordon Matta Clark.

I was drawn to a short film of hers, a brief loop of old film, showing a house being built, its walls precariously propped up by a group of men, and looking for all the world like it might collapse at any minute. The loop was short: they raised the wall, it collapsed, they raised it again, and so on. It reminded me of Buster Keaton at the time, but thinking back there was dimension to it that is unspeakably tragic.

Since that first meeting, we kept in touch, and recently Leykauf was kind enough to invite me to contribute a short essay to her new artist book from Roma Publications of Amsterdam. With the book’s publication imminent, it seemed a good time to catch up to discuss her current practice.

What are you working on right now?

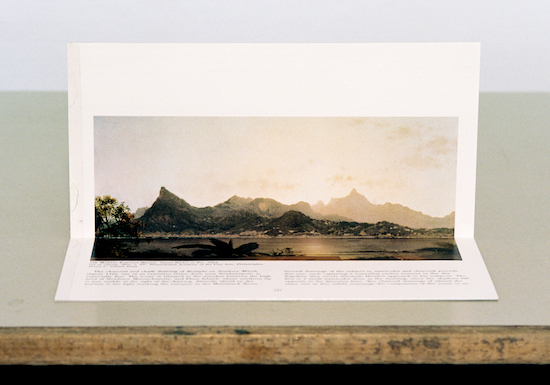

At the moment I am photographing depictions of landscape paintings and doing all sorts of things with them. I, for example, took photographs with a long exposure time while I was turning the page so that the camera captured two or more depictions (and the accompanying text) superimposed upon each other and merging into each other.

I always felt that the procedure of depicting a painting in a book creates a new work. Apart from the obvious change of medium – from paint on canvas to offset print on paper – the change of scale turns the painting into a miniature. Unlike the way we walk towards and alongside a painting on the wall, the way we move closer or back up to gain an overview, we don’t relate to the reproduced depiction in a physical way. We engage with it purely mentally, focus differently to the way we would if we were standing in front of the original.

Also, I am intrigued by the muddle of locations we are confronted with when looking at the reproduction of a painting: there is the site represented by the painting, and the museum or collection that houses the painting, both somehow brought together within the territory of the book.

“View of Gloucester Harbor + Becalmed off Halfway Rock (Fitz Hugh Lane)”, 2015, 63 x 88 cm, offset print

How would you situate these latest works in relation to your ongoing practice – in what ways does it continue or differ from your previous work?

The images I used within my work were often of self-contained spaces. Whether I have been dealing with motifs of the baroque garden, the carpet, the movie theatre, the museum, the tent, the vitrine, the cabinet or the book – there was often a designed interior surrounded by an undefined exterior, with me dealing with the interface of these spheres, asking myself on which side I position myself.

There’s always the question of direction: inside-out vs. outside-in. In a way these latest works move from the interior towards the open, towards the – albeit depicted – horizon, if you wish.

What continues is certainly a challenging of perspective and an observation of the act of looking.

There is an intimacy to books that somehow paintings struggle to achieve: you can read a book in bed at night, bring it right up to your face, carry it around with you all day. These are things you could never do with most paintings – at least not big, old landscape paintings. How does your process of rephotographing and manipulating the pages of a book affect and modulate this sense of intimacy?

The process of rephotographing and manipulating is my way of understanding the different parameters under which we look at images. I am glad you introduced the term “intimacy” because I find it far more fitting than “appropriation” in the context of my work. Both terms are similar in that they describe a process of occupying oneself with, and getting closer to, a certain matter. But whereas I feel that appropriation is one-sided, and turns that which is appropriated into property, intimacy is a bilateral affair.

I believe the lack of intimacy you notice concerning landscape paintings is not only due to a lack of availability, it is also caused by a whole history of pictorial conventions.

The invention of perspective established a division between subject and object. In perspectival representation the vantage point of the viewer actually remains unrepresented, a construction that allows for invisible observation: “looking at” as opposed to “being part of”. How can we be part of what we look at?

I would say the process of rephotographing and manipulating enhances – or even initiates – the sense of intimacy you describe, and I hope that I am able to transfer this sense to the viewer. To transfer, that is, a feeling of mutual availability.

Forest Landscape (Gillis van Conninxloo) Installation view Motto Berlin, 2014, ca. 180 x 500 cm, b&w prints

In my essay for your forthcoming book I talk about another recent work of yours involving landscape paintings, The Serial Universe. For that piece, you photocopied fragments of Gillis van Coninxloo’s Forest Landscape of 1598 and pasted them onto display cases at the Motto bookshop in Berlin. With its titular reference to the theories of the British philosopher and aeronautical engineer J.W. Dunne – whose book The Serial Universe of 1834 hypothesised a world governed by multiple, layered temporalities – this piece seems to be quite explicitly concerned with the overlapping of different times, whereas with this new work that we’ve been discussing, we’ve mostly been talking about an overlapping of spaces. But I wonder if there is also a temporal element to this work you are engaged with at the moment? How does time inhabit this work and how does this work inhabit time?

There is always a temporal element because even if we ascertain, for instance, a painting in one glance, time has already passed. We can’t picture that painting without engaging in some kind of relationship with it, and that always raises the question of our position towards that at which we look.

The photographs I took with a long exposure time while I was turning the page are maybe something like a reversal of [English photography pioneer] Edweard Muybridge’s pictures of a horse in motion.

There was a lot of excitement around these photographs in the late 19th century because people thought that they revealed what a running horse really looks like, what we would see if only our eyes were fast enough. But in the end those photographs teach us more about perception and the way we see than about a horse in motion.

In another experiment I filmed a landscape painting of Philips Konink at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, holding the camera as long as I could until I finally had to give up because my arm was trembling too much. It’s a bit annoying to watch, but I like the sense of physical presence it causes.

Your work often sets up a kind of dialogue between different media. In the practice we’ve been discussing, it’s a dialogue between painting and photography, for instance. But several of your films also resemble proto-cinematic technologies like the zoetrope or phenakistoscope. What is at stake here, what effects are you hoping to produce, by placing one means of representation inside another?

Within these latest works based on landscape paintings, I actually don’t only see a dialogue between different media but a whole range of mutual influences. If you think of the purely imaginary views of [French baroque painter] Claude Lorrain, for example, and how they have shaped the design of the English landscape garden, it becomes clear how not only our perception of nature but nature itself has been shaped by artificial concepts.

What I am trying to say is that those paintings may not be the first medium I am dealing with. They are, like my photographs, the result of a whole series of mediated concepts and express a historical, respectively contemporary, condition rather than simply giving us a view on “landscape”.

Generally and more practically it is rather the economics of means that guides my choice of medium than the intent to place one means of representation inside another. I always try to visualise what I have in mind with the simplest means at hand.

An example for a group of works where actually the museum itself was the initial means of representation are the “vitrines”. I photographed free-standing showcases in a number of museums from all four sides, always focusing on the background, i.e., on the interior of the exhibition space as seen through two screens of glass. I built wooden reconstructions of the showcases in their original dimensions, painted them grey and attached the photographs I had taken as black and white prints, replacing the glass of the showcases.

I often try to see how far I can reduce the amount of visual information. In the case of the “vitrines” the simple means I used distanced my work from the sense of preciousness that is inherent to any display in a museum.

Sometimes I have to reconsider my choice of medium. For example, I don’t work with 16mm anymore. For several of my films I chose 16mm because I wanted to show the physical loop in the projector, but also because I am comfortable handling a 16mm camera and it seemed a logical and easy way to shoot a short film.

But 16mm became rapidly out-dated and the projectors started to draw too much attention to themselves within an exhibition. They became fetishes. I had to realise that the choice to use 16mm wasn’t obvious anymore and overlaid all the other choices I had taken.

Installation view Wiederholen, Westfälischer Kunstverein Münster, 2014

Though there remains some debate on this issue, it seems that in most countries a photograph of an-out-of copyright painting is generally deemed to reside, also, in the public domain as long as it doesn’t significantly add anything to the original painting. So Wikipedia, for instance, is free to post a photo of the Mona Lisa. But in a sense your thoughts on photographic reproduction imply that a photographic reproduction always adds something to and changes something about the original. How do you resolve this seeming aporia, that your own thinking about your work problematises the very legal loophole that (in some sense) makes your practice possible?

The flip-side of the rule that an out of copyright painting can be reproduced and published as long as the reproduction doesn’t significantly change the original would be that an artist’s property rights aren’t infringed as long as the work is changed significantly. How much change is deemed “significant” is continually interpreted through court cases.

I think the law is a bit lost here, trying to introduce different percentages that are supposed to determine the dividing line between one authorship and the next, but as we know since the first readymade: a significant change may simply be a change of context.

I think that the legal aspects of “reproduction” in the broadest sense, be it the purposeful forgery of a painting or a photograph shared on the internet, are secondary to the issue of what defines an original.

In a way, there wouldn’t be any tradition and there wouldn’t be any progress if an author’s invention was considered untouchable. Misunderstandings about the original and its context are probably a major force in the creation of new work.

It can, for example, be argued that the cool, dry style of 19th century American landscape painters, like Frederick Edwin Church or John Frederick Kensett, has its origins in the engravings of European paintings they studied in place of the originals – which just weren’t available to them without travelling across the Atlantic.

I am also thinking of a house of cards. It’s not poker players who build a house of cards, but people who might not even know the rules. It would be a pity if cards were only used in the way they are meant to be.

Alexandra Leykauf’s new book will be available soon from Roma Publications