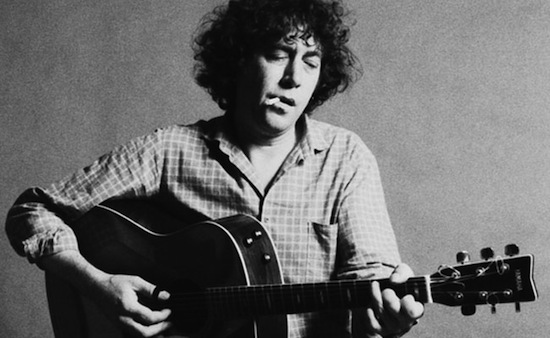

A messy thatch of black hair and sideburns gazing back at the camera, a beehived girl on the floor… the cover of It Don’t Bother Me, Bert Jansch’s second solo LP, shows that ’60s folk music wasn’t averse to myth-making. He had chops, though, did Bert. A wilful character brought up in the tenements of Edinburgh by a single mother (one who inspired her children to play music by saving for a second-hand piano), he built his first guitar at 12, bought his first on hire purchase at 16, and became a regular at Edinburgh’s Howff folk club soonafter, where he lived after giving up a job as a gardener. The next five years before his debut album arrived were of Leonard Cohen-grade legend: squatting in squalor with The Incredible String Band’s Robin Williamson, busking and playing through Britain and Europe with a girlfriend he married because she was too young to get a passport (they divorced pretty quickly), being deported from Tangiers back home on the way to Marrakech to make music (less mythically, he had contracted dysentery), and returning to a booze-and-weed fuggy flat chock-full of folk musicians, albeit in less exotic environs between Cricklewood and Kilburn.

His half-century-career as a whole was a restless route through folk, jazz and the blues, his guitar-playing anarchic as well as masterly, as coarse as it was cultivated, his voice similarly brutish, but never not beautiful. A huge, direct influence on Neil Young, Jimmy Page and Paul Simon’s much more mainstream music, listening to Jansch is like reading an original, brilliant, spontaneous draft of those artists, stained with ink, grit and smoke, and jaggedly alive.

‘Courting Blues’ (from 1965’s Bert Jansch)

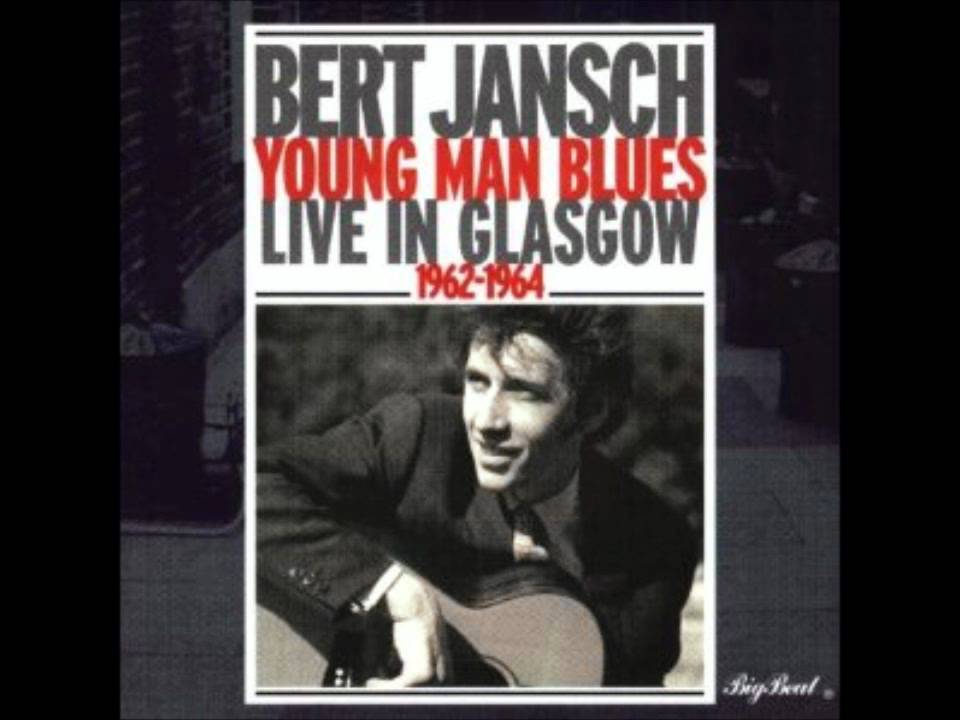

Jansch wasn’t an original out of nowhere: two musicians made specific, huge impacts on his sound and his style. The first was the 16-year-old Anne Briggs, who had cycled from Nottingham to Edinburgh in the summer of 1960 to stay with her and Jansch’s friend, Archie Fisher, himself an accomplished Scottish folk singer and songwriter. In Colin Harper’s biography of Jansch, Dazzling Stranger: Bert Jansch And The British Folk And Blues Revival, Fisher says that ‘Courting Blues’ – one of Jansch’s first originals – was written at that time. “[Bert] hadn’t been playing for very long but he was obviously a born guitarist. He was playing amazingly good music, very individual music… [‘Courting Blues’] was in the process of getting together.” Its first verse sets its charged, erotic tone plainly: “Green are your eyes/ In the morning, when you arise/ Don’t you be afraid to lie/ By me, my love/ Your father will not know.” A hugely pioneering folk singer in her own right, Briggs was also the person who took record shop worker and part-time producer Bill Leader “firmly by the throat” in 1964, and demanded he record Jansch, whose live reputation by this point was impressive. This song was captured soonafter by a reel-to-reel tape recorder in Leader’s Camden kitchen, soundproofed with blankets and egg boxes, as was the rest of Jansch’s 1965 debut album.

‘Angie’ (from 1965’s Bert Jansch)

Jansch became aware of the half-Scottish, half-Guyanese guitarist Davy Graham through his half-sister, Jill Doyle in 1960, who gave Jansch guitar lessons (“I fell madly in love [with her]”, Jansch told Harper, years later). Doyle was sent a tape of her brother’s first EP, 3/4 AD, in early 1962, which featured this then-groundbreaking blues instrumental. Jansch’s version on his debut album has a rollicking momentum, the jangled, strummed flourishes at ends of lines full of urgency and fire. (He also throws in a portion of Nat Adderley’s jazz standard in the middle, nodding towards the directions his playing would take.) Jansch also sat in on Shirley Collins and Davy Graham’s sessions for Folk Roots, New Roots, their stark, experimental romp through traditional song. Graham’s African and Eastern influences only pushed Jansch’s tastes out even further.

‘Needle Of Death’ (from 1965’s Bert Jansch)

Ballads about heroin weren’t ten-a-penny in the mid-’60s, especially when with lyrics this poetic, but powerful: “One grain of pure white snow/ Dissolved in blood spread quickly to your brain/ In peace your mind withdraws/ Your death so near your soul can’t feel no pain”. Jansch wasn’t a hard drug-taker himself (“he was a 26-pints-a-night man”, Pentangle’s Danny Thompson told Uncut in 2010), but this song was autobiographical – about a friend of Jansch’s, Buck Polly, who overdosed in June 1964, having lived a very troubled, short life. In JP Bean’s Faber history of British folk clubs, Singing From The Floor, Colin Wilkie recalls Polly having "a photo of his baby son, who I believe, had died, stuck to the inside of his instrument case… I recall Buck being a nice lad, but as troubled as the song says." Jansch marries a hard, uncompromising lyric with one of his prettiest tunes, which directly influenced Neil Young’s ‘Ambulance Blues’, itself written when Young was beset with drug problems. ‘Needle Of Death’ was also covered memorably by Yo La Tengo in 2003 on their Today Is The Day EP.

Anti-Apartheid (from 1965’s It Don’t Bother Me)

Jansch wasn’t one for politics generally, attending a Vietnam protest march with Joan Baez and Roy Harper in May 1965, and only making a few direct pronouncements in his work. One notable example is 1965’s anti-nuclear protest song ‘Do You Hear Me Now’ (“Can you see those mushrooms seed and burst?”), which Donovan made a hit on his Universal Soldier EP later that year, as is ‘Bring Your Religion off 2006’s Black Swan. This small, arresting song is often forgotten though, driven by a beautiful, minor-key guitar figure, and that tough, rough-cut voice. The lyrics are often plain and obvious (“I cannot bear to think of people cast aside/ I fail to see the reason why of colour you must hide”) but they pack more of a punch when they stray into abstractions (“To separate the colours and break the rainbow sign/To ask the finest painter to draw a crooked line/Will only slow the journey to here again another time”). A last verse about a one-race world creating “a daily gift of boredom” underlines how liberal, how curious, how searching Jansch was.

Black Water Side (from 1966’s Jack Orion)

Jansch’s influence on bigger artists cannot be underestimated. Paul Simon included ‘Angie’ on 1966 LP Sounds Of Silence after following Jansch round on the English folk club circuit. Jansch wasn’t a fan, though. “He was always telling me he was going to make it one day, and he’d actually bore me… I don’t have a very high esteem for America”, he says in Harper’s biography. Jimmy Page has also admitted to being “obsessed” with Jansch’s playing in the mid-’60s, having obviously heard ‘Black Water Side’ on Jack Orion… before Led Zeppelin released their 1969 debut album, which included a track called – one minute! – ‘Black Mountain Side’. Page claimed this unusually familiar piece of music as his own composition on the liner notes, but legal letters to the band curried no favour; Jansch couldn’t claim copyright either as the track was traditional, taught to him by Anne Briggs, who knew it from collector Bert Lloyd. Jansch’s label were peeved, but their boy shrugged the matter off. “Page plays all this stuff but he doesn’t recognise it as being folk music,” he said, smiling, years later, in the 1992 documentary about his life, Acoustic Routes. “He just plays it, and it comes out as heavy metal.”

Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (from 1966’s Bert And John)

In 1964, Jansch met guitarist John Renbourn, and they soon became housemates. “At Somali Road, me, John and [singer/guitarist] Les Bridger were upstairs,” Jansch recalls, once again in Harper’s biography, “and downstairs was a group called The Young Tradition who were an a cappella traditional… mob. The place was mayhem. They made more noise, drunk more, and smoked more dope than anybody else. And they also had personal friends like Spider John Koerner, these American bluesmen. It never stopped – it was 24 hours.” Here, Jansch and John Renbourn’s musical partnership would blossom and burn, with a mutual interest in jazz became a bigger part of their lives. This cover of Charles Mingus’ 1959 elegy for saxophonist Lester Young, on their first album together, is lazily, drowsily, shiningly lovely.

Soho (from 1966’s Bert And John)

Jansch’s greatest original. A bright, sad guitar line draws you into its world, before lyrics paint the the dark, rheumy heart of a lost part of London. Here are people: “See the dazzling nightlife grow/ Beyond the dawn, and burning… here the market cries… come watch the naked dance”. Here is drink: “Step inside, where men before/ Have drunk their fill to senseless/ Their dreams fade and die… Does the blood red wine come flowing/ From the glass to your veins?”. Here is rest too: “And the midday dream is silent/ In the gardens where you’re resting/ From the troubles of your mind." From the pubs of Greek Street and stalls of Berwick Street to the softness of Soho Square… no distressed lifestyle cafes or perspex developments here, and music’s all the better for it.

Light Flight (as part of Pentangle, from 1969’s Basket Of Light)

By the end of the ’60s, Jansch had big commercial success, unbelievably, with folk/jazz rock group Pentangle. Alongside John Renbourn, bell-voiced singer Jacqui McShee, plus jazz bassist Danny Thompson and drummer Terry Cox, their first ever concert at the Royal Festival Hall was a sell-out, partly because Jansch’s legend lingered well at this time (his first album sold 150,000 copies). They also had a top 5 album with 1969’s Basket Of Light, largely because of the success of this track as a single. A slyly funky song in 5/4 about someone wanting to escape the “city race”, it was also the theme music to the BBC’s first ever colour drama, Take Three Girls, about three Swinging London female flatmates. It goes properly psychedelic in its middle too, with a slowed-down, wordless section, before McShee returns drowsily, exploring the elements: “Swirling, the waters rise up above my head/ Gone are the curling mists how they all have fled/ Look, the door is open, step into the space provided there.” Also listen to their eerie, terrifying version of Yorkshire traditional song Lyke Wake Dirge, about the soul’s travel to purgatory. Pop hauntology, brethren, begins here.

‘Avocet’ (title track from 1978’s Avocet)

After his glorious early days, Jansch’s mid-career doldrums included many surprising moments: Tony Visconti playing electric bass on 1973’s occasionally lovely Moonshine, a sentimental but deeply affecting take on the Christmas standard ‘In The Bleak Midwinter’, and this beautiful 1978 album, Avocet, about British birdlife, which has been recently reissued. Its eighteen-minute title track is a weird, whirling creature, beginning as beautifully as a bright summer’s morning, before Martin Jenkins’ double-tracked violin violently weaves in and out, sounding at times like an experiment in woozy electronics. A slower, ambient section, almost medieval at times, then buds into the song’s final minutes, joyously, gently.

‘All This Remains’ (with Hope Sandoval, from 2002’s Edge Of A Dream)

In the last fifteen years of his life, Jansch was suddenly everywhere again, partly because of the encouragement of his second wife, Loren. There he was, playing with Bernard Butler and Johnny Marr on TV in 2000 (both often cite him as a hero), recording with Beth Orton and Devendra Banhart on 2006’s Black Swan, touring, unbelievably, with Babyshambles, in 2007, and reforming Pentangle for reunion shows in 2008. He died in 2011 at the age of 67, of lung cancer. His 2002 album Edge Of A Dream remains that period’s most overlooked beauty, featuring some beautiful playing, and some great collaborations, especially this stunning, ghostly track with Mazzy Star’s Hope Sandoval. “I’ve been seeing you/ In this house of mine”, she sings, “The shimmer on the ends of my memories/ I could feel your ghost/ In the breeze”. Her voice takes you back to older sounds and older times, and the magical sense Jansch always brought to his music. Listen closer to the many more musicians that credit him as an influence these days, and those ringing notes, those adventures, that he brought us play on.

The reissue of Avocet is out now on Earth Recordings