Kanye the Producer

Let’s dispel a myth. Kanye The Producer is real. Not only is Kanye The Producer real, but by all counts Kanye The Producer pre-dates Kanye The Rapper.

In March 2015 MTV published an article entitled (and, unsurprisingly, detailing) All 21 People Who Wrote And Produced On Kanye West’s ‘All Day’. While the list pre-dates that summer’s Drake vs. Meek Mill feud, it’s very much a harbinger of that beef and the point it makes is equally barbed: to highlight, in an industry that hinges (though less and less) on the concept of authenticity, West’s apparent spuriousness as anything other than a vessel for the talent of others. It may seem innocuous, a kind of “facts-are-facts, here for your information” list, but the “not a real producer” jibe is one all-too-often leveled at Yeezy in the same way that “not a credible artist” is hurled at Beyoncé.

21 days later Spin put forward a considerably more effective counter case: ‘The 101 Best Kanye West-Produced Songs That Don’t Feature Kanye’ is a veritable who’s who of artists and name-brand singles – including, arguably still one of Jay Z’s most popular singles to-date, ‘Izzo (H.O.V.A.)’ – that have been demonstrably boosted by ‘Ye’s talents in a non-performative capacity.

In short, that Kanye has nothing to offer on a production level is demonstrably untrue – a theory, like Count Adamar in A Knights Tale, ultimately weighed, measured and found wanting.

What, if anything, that list of 21 contributors to ‘All Day’ (and the more recent hand-scrawled sign-in sheet for The Life of Pablo) actually points to is an ability to collaborate and curate with some proper fucking nouse: a gift for identifying, harnessing and knowing when best to use the talents of others. It’s a stellar skill in and of itself, but it’s also indicative of something more, running contrary to and even going someway toward disproving the overarching narrative of extreme narcissism and self-mythologisation that has come to be synonymous with Kanye West.

College Dropout

College Dropout as a title is one of the biggest misnomers in musical history. Not in any way that pertains to formal education, but just in terms of the cultural connotations of failure that it points to: rather than dropping out, the album picked Kanye out of relative production obscurity (yes, we’ve established Ye was a successful producer; no, that absolutely doesn’t compare to his stature as an artist) and dropped him in at the forefront of audience-facing performing artistry. Where the title actually does make sense is in the way it signals vocation: College Dropout was a learned-on-the-job affair, crafted and polished in small sections at a time and rescued from the brink by hard work and determination: leaked before its intended release, the album was re-worked, chopped up and sculpted into something far beyond what it might have been.

Like the eponym, too, the album was a declaration of intent – a mission statement to prove that traditionally held ideas of the music industry (most notably that “if [he] talk[s] about God [his] record won’t get played”) were not incontrovertible truths; they were just ideas, and they were wrong: ‘Jesus Walks’ made 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, the album went triple platinum and the myth of faith as the last great taboo in popular music was at least partly dissolved, in no small part re-shaping the landscape. What Johnny Cash never quite managed to do — the gospel stuff is alright — Kanye came closer to achieving with only his first solo album.

808’s and – more importantly – Heartbreak

Other than T-Pain and Cher, nobody in recent memory has done as much for auto-tune as Kanye West – even if, according to the former, he’s actually been using it wrong this whole time. Without 808’s there’s a strong case to be made that we wouldn’t have Drake and The Weeknd as we know them, or even the mechanical swirl of Bon Iver’s Blood Bank EP.

On the other side of the coin, auto-tune hasn’t done as much for anyone as it’s done for Kanye West: at a time when West was done with hip hop as a narrow platform (wanting instead to be considered “alongside only the musicians you see in the old black-and-white photographs”), physically and emotionally chewed up, swallowed and shit out through the eye of a needle, auto-tune facilitated a sea change in his music. Where the pervading idea is that auto-tune as an instrument is inherently false, a flimsy mask to cover a dearth of talent, 808’s And Heartbreak proved beyond reasonable doubt that there is as much scope for auto-tune as a vehicle for honest self-expression as any other instrument.

Reeling from the unexpected loss of his mother and the break-up of his relationship, the braggadocio of ‘Power’ no longer made the grain for an artist looking at the world newly-unobscured by shutter shades. The evolution documented in the education triptych – from College Dropout to Graduation – had reached its inevitable end-point and progress could only now be achieved through a razing and creative rebirth.

808’s wasn’t slick, it wasn’t polished, self-assured or high on itself. Commenting on the performance of ‘Love Lockdown’ on Letterman, Pitchfork notes that “[t]he song called for him to sing alone, and he botched the first take in front of the studio audience. On take two, he still sounded shaky, badly missing a note even with real-time pitch correction software. But his body was twanging with effort as he gripped the mic stand for balance while heaving himself into the music,” and in doing so captures the spirit of the album as a whole. Raw, naïve – even childlike – in its forthrightness, and inherently powerful in its forthcomingness; in its total surrender of power.

According to the same article, “Kanye West had always been audacious, but this was a new kind of wire-walk,” and in a sense that’s true: auto-tune allowed Kanye to consciously expose his own human weaknesses. Audacity via negativa.

Yeezus Interruptus

In 2009 even my nan knew – if not exactly who he was – that Kanye West existed. (NB: I love my nan, and I’m well aware that generally speaking nans absolutely can have an excellent cultural grounding and pedigree of taste. My nan is not one of those people though: she likes late-afternoon TV quiz shows presented by mild-mannered hosts like Ben Shepherd and complaining that no-one calls her while simultaneously not calling anyone herself.) Interrupting Taylor Swift at the VMA’s didn’t make Kanye famous (though there’s some debate about the flip side of that), he already had four incredibly successful albums under his belt by that point, but it did go some way toward cultivating the idea of Kanye West as an idea and as a man with ideas.

Of course, it also established the narrative of Kanye The Jackass: a man who didn’t know how to pick his battles or how to effectively single out and demonise (intentionally or otherwise) the right bad guy. Whether Taylor Swift or Beyoncé should have won that award in the first instance is almost irrelevant: shitting on one of a young artist’s first real moments – not just of stardom, but also of acceptance by the public en masse – seems counterintuitive. It achieved nothing (they didn’t retract Swift’s award and give it to Beyoncé, if you can believe that) and told us more than we – or he – wanted to know about Kanye West.

It wasn’t a complete failure, though: this proto-outburst set the stage for a more effective barrage six years later when he disrupted yet another apparently undeserving winner’s acceptance speech at yet another awards show.

Now, if you’ve seen the Beck episode of Futurama, you know without question there’s no more authentic artiste than the scientology cowboy. I don’t know if Kanye watches Matt Groening’s animated sci-fi soap, but I know that he does understand artistry – so it begs the question: what the fuck was he thinking by implying anything else?

As with most things Kanye there’s a diverging flow chart of possible answers: on the one branch, not only is Barack Obama absolutely right – Kanye is a jackass – but, and this wouldn’t be the only evidence, he’s also a misogynist who perceives his culturally internalised misogyny as chivalry, counteracting his own very real desire for social justice. The other branch – and there’s also a lot of evidence for this, too – points to the fact that Kanye West is a man well ahead of his time: #OscarsSoWhite was but a twinkle in Jada Pinkett Smith’s eye, but Kanye West has never been the sort of person to allow even an unformed idea to go unarticulated – and, perhaps as a result, doesn’t always choose his words wisely. Awards ceremonies absolutely do “lack respect” and have always assumed that black artists need awards more than awards need black artists. (Case in point, neither Drake nor Nicki Minaj played this year’s Grammy’s despite being billed to appear. The assumption presumably that they’d appear if they were told they were appearing.) They purport to honour artistry but, for the most part, artistry means White Artistry potentially unrelatable and even alienating to a huge percentage of the population.

“[W]hen you keep diminishing art and not respecting the craft and smacking people in their face after they deliver monumental feats of music, you’re disrespectful to inspiration… And we as musicians have to inspire people who go to work every day, and they listen to that Beyonce album and they feel like it takes them to another place.” It was more eloquent than “I’mma let you finish,” a more refined idea, but still ever so slightly misjudged: instead of “Beck needs to respect artistry and he should’ve given his award to Beyonce,” he might have refocused and taken aim at the institution – rather than a fellow artist who subsequently acknowledged his right to be on that stage “as much as anyone” and his status as a “genius.”

To quote Modest Mouse, it was "well intentioned but bad advice (hell yeah)".

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

Having called out College Dropout for its misleading quality as a title, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is nothing if not the opposite case study: I’m not sure I can think of anything that beats it in the honesty stakes. When I interviewed Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon back in 2011, the memory of working on MBDTF was still pretty fresh in his mind and it was obvious there was nothing but (mutual) admiration between the two of them. In addition to insisting that Kanye was hyper-intelligent, that other people are racist, and that West was capable of staging productions in a live environment that he could barely even comprehend, he also alluded to an apparent fascination with monoliths — a real love of big fucking rocks.

It seemed like a by-the-by at the time, but in context it makes perfect sense: MBDTF is superlative, maximal, extroverted and — yes — monolithic. As much as any album can be, it was a Jungian fantasy: Rolling Stone‘s Rob Sheffield noted that "coming off a string of much-publicised emotional meltdowns, Yeezy [was] taking a deeper look inside the dark corners of his twisted psyche," and in doing so more or less hit the nail on the head. If 808’s was an act of autobiography, MBDTF was both personal sublimation at its purest and a sprawlingly complex rendering of the collective unconscious; hailed for both a "pathological allegiance to expressing [Kanye’s] emotions, unfiltered" and a "hedonistic exploration into a rich and famous American id", it was an album intended as much as social catharsis as it was personal expression.

Simultaneously both sprawling and transparent, towering and oblique, from ‘Monster’ to ‘Lost In The World’, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was jam-packed with residual Kanye West — with ideas from and echoes of his previous work and his previous avatars — as much as it was so expansive to be completely devoid of ascribed meaning, waiting for the imprint of the listener to project and divine their own meaning. Not just a monolith, but also a mandala.

If Kubrick and Lynch had worked together on a film of the Manson Family murders — and more’s the pity that will never happen — it would be as close to MBDTF as any other work of art. Our Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

Watch The Throne (he’s coming for it)

If My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was Kanye’s journey deep into the unconscious, both collective and personal, his 40 days in the desert — the Last Temptation of West — Watch The Throne is the begrudging acceptance of his place in the world: alongside Jay Z, whose lyrics have consistently focused on the accumulation of material goods and power, ‘Ye and Jay alternate between hedonism and spiritualism (between good and evil, id and superego) to expand upon and narrate, ultimately appearing to denounce the themes that took centre stage in MBDTF.

The sensual self-indulgence disguised as faith ("Lost in this plastic life / Let’s break out of this fake-ass party / Turn this into a classic night / If we die in each others arms, still get laid in the afterlife") so brilliantly articulated with MBDTF, is replaced ("When we die, the money we can’t keep

But we probably spend it all ’cause the pain ain’t cheap") with a concession to the fallibility of mankind and potential futility of the task at hand on Watch The Throne. Yelling preach into the void.

But, as much as Watch The Throne is social commentary — on the nature of black aspirationalism sold as the antidote to persecution, on faithlessness in a material world — it’s also an assertion of power. To have any reason to watch the throne you either need to have designs on that seat, or to already possess it. It’s a reading distilled to absolutely purity in the refrain of ‘Gotta Have It’: "What you need, what, what you need / What you need, what, what you need / Oh (I got what you need)". As a statement it seems potentially throwaway on the surface, but it effortlessly casts a light on the classism of Have vs. Want vs. Need, simultaneously attacking that system and declaring Kanye and Jay Z’s place within it.

Yeezus The God

Another myth to bust: Kanye The Rapper exists, that’s self-evident, but what isn’t so obvious — or is quite often wilfully and skilfully obscured, is that Kanye The Rapper isn’t actually that great. This one’s slightly different, because it’s a myth established by West himself and perpetuated wholesale as an idea all over Yeezus even as it proves itself to be false. For example: in ‘I Am A God’, the lyric "In a French-ass restaurant / Hurry up with my damn croissants" is immediately followed — no less than three times — by the "I am a god" refrain. It’s one of the most impressive paradoxes I’ve heard in music, and you have to wonder whether, actually — in retrospect — it’s one of the most self-aware, too.

But, if Kanye The Rapper has never been a shining light — operating the controls from behind the curtain, effusing but never demonstrating the scope of his talents for years now ("Bow in the presence of greatness / ’cause right now thou hast forsaken us") — then you might ask exactly how Yeezus is any different. The question brings to mind a quote from Kevin Smith’s Dogma, where Rufus the 13th apostle (left out of the Bible for being black) explains Jesus’ problem with religion: "humanity took a good idea and, like always, built a belief structure on it… it’s better to have ideas. You can change an idea. Changing a belief is trickier." It’s not too much of a stretch to apply the same principle to Kanye’s sixth solo studio album; just replace "belief" with "album". Hearing Kanye so eloquently explain to an unusually quiet, near-impossibly humble Zane Lowe exactly why it’s racist to tell him that he’s not a god, or the palpable quasi-Marxist feeling of rage that hangs over songs like ‘New Slaves’ like an oppressive fog, the ideas are not only so clearly there but also so obviously good.

The reason, then, that Yeezus stands out as a low point for Kanye The Rapper is because for Kanye The Artist it was a high watermark. In a way, West has more in common with someone like Ai Weiwei than any of his musical peers: rather than hinging on technical proficiency, of the mastery of his supposed craft, it’s the concept behind and the public articulation of each creation that has the most to offer. For Kanye the idea is the craft.

Kanye The Designer

Pre-Adidas but post-a whole other load of collaborations from the aborted Bape line to Luis Vuitton footwear, Kanye West was too famous to enrol at Central Saint Martin’s to hone his craft as a burgeoning designer – which, in retrospect, is something of a body blow for poor Antonio Banderas who, apparently, was just the right amount of not famous.

Brushing off the indignity of celebrity, West partnered with Nike on the Air Yeezy – which, like all subsequent editions of the trainer, sold out and prompted absolutely insane resale values – and ultimately managed to pole vault a formal education in design, landing eventually on the crash mat of the Yeezy Season Adidas collaboration.

Compartmentalising its subjective aesthetic quality – personally, I’m into it – now in its third incarnation, Yeezy Season is at best a well-meaning oxymoron and at worst a frustrating exercise in hypocrisy: purporting to take inspiration from the 2011 London riots for Season 1 and presenting Season 3 in a way that “could not have been a more graphic statement about haves and have-nots in an increasingly polarised society” seem like solid, if not divisive, concepts. On the other hand, of course, it’s possible to read the whole thing as a personal crusade on behalf of a damaged ego: from rejection by the institution five years earlier, to seeing Vogue’s Anna Wintour sat next to his family at the Madison Square Garden premier of his third full line. A move to establish the narrative of Kanye West very much as a "have".

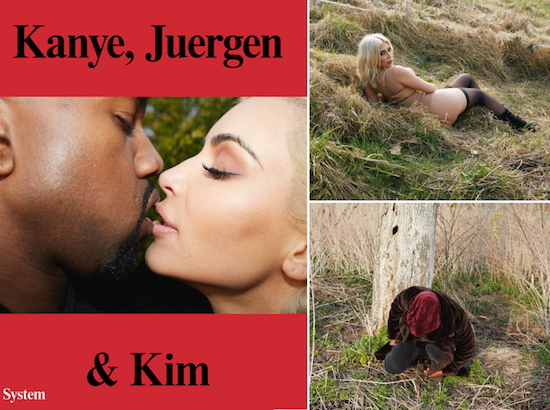

Kanye & Kim (as shot by Jurgen Teller)

In the grand scheme of Kanye West’s illustrious career, this peculiar episode might barely seem worth footnoting – but that’s a way of thinking that relies on the misconception that when we talk about Kanye West’s career we’re talking exclusively about his musical output. And that just doesn’t make sense. Like it or not – fuck, blame Andy Warhol if you want – the cross-cultural cultivation of celebrity status is as much key to who Kanye West is (or at least the public avatar of Kanye West) as his discography.

For some – most notably those keen to actively find a reason to bemoan contemporary popular culture – it’s yet another marker of vapidity. To others it shows an intelligent, wholesale embrace and understanding of what it means to be an artist in the twenty-first century. It’s for this reason that the photo series depicts West and Kardashian not in their respective basic cultural roles as musician and television personality, but also not as entirely human individuals: dominating frames of natural landscapes, towering above and resplendent in juxtaposition against death, the images establish the couple as larger than life. It goes beyond the notion of what they do and acts as a monument to what they are.

2016 JPP (just pre-Pablo)

“A ‘brilliant madman’ who speaks and acts in superlatives.”

Until very recently this definition – a combination of Dorian Lynskey’s own ruminations on the pages of the Guardian and their natural partner in the words of Madonna – was a standard description for Kanye West: a distilled Portrait of the Artist as an Artist which, though perhaps lacking in the finer details of Kanye’s narrative arc to date, was difficult to argue against regardless of your personal take on that same portrait of the artist as a Man.

And to some extent that’s all still true. But, to mix literary metaphors, in recent weeks (notably in the lead up to the release of his seventh album, So Help Me God, SWISH, Waves, The Life of Pablo), and in the absence of any major release of new music for the last three years, there’s been a sense that the aforementioned portrait of ‘Ye the man – hidden in an attic room, degrading under the weight of its own expectation – has been given a more prolonged public viewing than usually permitted.

Only two months into 2016 and the world has been treated heavily, via the magic of Twitter, to Stream of Consciousness Kanye: a more erratic version of the Taylor Swift-interrupting, Bush-bashing West that – however misguided in action, and even if not always right in intention – more often than not at least had a kind of naïve nobility on his side.

Dropping (sadly now far from unexpected) casual misogyny bombs on Amber Rose, unequivocally stating his support for Bill Cosby without context, and posturing in extremis by hosting the world’s most ostentatious listening party for an unfinished album. This is the Kanye West we have now, one who seems actually less Dorian Grey and more Macbeth – in maddening awe of and utterly beholden to his own near-realised self-fulfilling prophecy, possessed by the notion of a destiny, the loudest exponent of his own mythology and subsequently also the most likely architect of his own potential demise. As Kanye so eruditely put it back in 2010 and history has been telling us for significantly longer: “no one man should have all that power.”

Of course, that’s only one way of looking at it. Another, almost the reverse, is to say what we’re actually seeing is Kanye West at his most self-aware: that not only does Drake have a bigger pool than Kanye, but has also perfected something Yeezy is only just starting to understand – that nothing in twenty-first century culture happens in a vacuum and isolationism is tantamount to onanism. From ‘I Love Kanye’, a track appearing on The Life Of Pablo, to the easily replicable meme-ready quality of its artwork – it’s possible, if unlikely, that Kanye has learned the golden rule of success in the Contemporary: that serving yourself up is more effective than talking yourself up.

follow @karlthomassmith on twitter