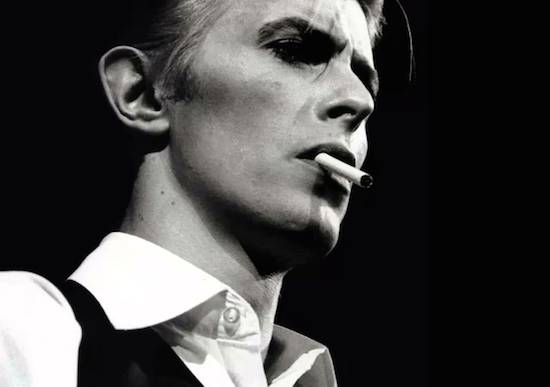

David Bowie will not be mourned first and foremost as a politicised figure. In fact, if anything, Bowie turned pop music into art by stressing its artifice, and for a chameleonic avoidance of any sort of conviction. From the start, he was an able post-modernist, heralding a new type of a pop idol. He was glamorous and protean but not empty; rather wearing his surface as his depth with pride. He also announced a new world, in which heroes in the old sense of History won’t be needed anymore. A consumerist culture of "heroes for a day" will replace everything: the state, politicians, ideology. Except not quite. Bowie himself stumbled repeatedly on the old rails of apparently forgotten or bankrupt 20th century ideologies.

Last week, coverage of Bowie’s death also prompted the unearthing of several stories of the singer’s less proud moments, such as his initial dubious interests in Nietzscheian "Homo Superior" and and alleged interest in fascism

Yet Bowie understood, even if instinctively, the force of the appeal of an idol as a quasi-political, or even fascist leader and flirted with forbidden aesthetics and politics. Most of all, the Cold War haunts his work. At the same time, as somebody boldly toying with camp and queer attitude, he was briefly a figurehead of the LGBT movement, although many were critical of Bowie using the social outrage of homosexuality for rather promotional reasons.

Another aspect was his early and problematic appropriation of black music. Those aspects made him a target in a famous critique of punk by Dick Hebdige, in one of cultural studies’ founding texts, Subculture. The Meaning Of Style (1979). Hebdige accuses Bowie of "colluding with consumer capitalism’s attempt to re-create a dependent class" of youth as passive consumers and not independent groups/classes questioning the transit to adulthood and the world of work. As he observes, Bowie wasn’t interested in any form of politics, social issues or in working class culture, at least in its traditional meaning, but he was also not interested in anything having to do with the ‘real’, and based his message on conscious escapism from the ‘real’ word. And yet, he was the one to unearth the repressed questions of gender sexuality and queerness, which back then in the 1970s really weren’t the talk of the day. As Hebdige observes, with Bowie and other glam rock artists such as Roxy Music subversive questions were shifted from class and youth towards gender and sexual identity. Yet, in the end, even a Marxist critic must appreciate Bowie-inspired youth’s attempts – via cross-dressing and make-up – to defy the easy transition of a youngster into a conformist society. And perhaps because of these contradictions, Bowie demonstrated the limits of popular culture as a source of emancipation in a larger sense. However, even if not straightforwardly, Bowie’s work frequently reflected the complicated politics of his time, both domestically in the UK, and a wider political canvas of America and the Soviet Bloc. What’s more, as author Phil Knight suggests, he was a true cultural "magician" and a symbol of the baby boomers’ culture. The passing of such figures as Bowie (and within the current climate of often right wing politicians, not pop stars, dictating the general discourse) suggests a larger disappearance of liberal values: "It is possible that not just Bowie, but the entire cultural movement in which he played a central part, may in the not too distant future appear an incomprehensible curio, an aberration that evolved from specific and unrepeatable social, cultural and economic conditions."

Bowie reflected the discrepancies of the era. He was a child of the welfare state Britain: born in 1947 to Margaret "Peggy" Burns, a waitress, and Yorkshireman Haywood Stenton Jones, who worked as a promotions officer for the Barnardo’s charity, and grew up in a southeastern suburbs of Brixton and Bromley. These were not glamorous surroundings, After dabblings with Mod and music hall, he swiftly moved on to the hippie subculture, and immersed himself in all kinds of dubious mystical drivel, from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra to Aleister Crowley’s occult – but had a less commonplace fascination with the Soviet space programme and the paranoid dystopian visions of William Burroughs, where modern civilisation is taken over by queer aliens. Bowie’s dodgy fascination with totalitarianism stems from this time: Hunky Dory and The Man Who Sold The World both contained vague paeans to an Ubermensch concept. Yet at the same time there’s mourning of depoliticisation. ‘Life on Mars’, for instance, moves from its girl losing herself in ‘the silver screen’ to the more collective escape of "the workers have struck for fame", with ‘"cause Lennon’s on sale again" being so odd in that context, perhaps who Bowie really had in mind was rather Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. In ‘Star’ is an odd reflection on the Labour movement. "(Aneurin) Bevan tried to change the nation", he sings, and dismisses such a hope with "I could make a transformation as a rock & roll star".

Always too erratic to make any firm political commitment, he was, nevertheless, obsessed with a particularly dark form of politics. He was driven to German culture, especially the Weimar period, expressionism, Neue Sachlichkeit, Betholt Brecht. (He studied theatre, was a qualified mime and used his acting skills to a great effect in videos, but also played John Merrick in theatrical play Elephant Man in 1980 and of course, sang several songs form the Brecht/Weill repertoire and adapted Brecht’s play Baal for the BBC/recorded an EP in 1981, providing compelling performances.) Fascism in general seems to have intrigued him: Ziggy Stardust regularly played in front of a lightning-flash logo borrowed from the British Union Of Fascists, which he later painted across his face for the cover of Aladdin Sane. It was unclear how much this was ‘about’ making links between dictatorial power and pop stardom and how much Bowie took the project seriously. In the mid-1970s, fueled by his rampant cocaine habit, Bowie went as far as saying in several interviews how "Britain is ready for a fascist leader… I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader.… I believe very strongly in fascism, people have always responded with greater efficiency under a regimental leadership…Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars…You’ve got to have an extreme right front come up and sweep everything off its feet and tidy everything up." This culminated in the infamous ‘wave’, interpreted as Nazi salute, at Victoria Station in 1976.

Bowie was targeted by anti-fascist organisations such as Rock Against Racism. He also attracted the attention and sympathy of the National Front, who in an article called "White European Dance Music," suggested that "Perhaps the anticommunist backlash and the aspirations towards heroism by the futurist movement, has much to do with the imagery employed by the big daddy of futurism, David Bowie." This ‘futurism’ was never quite as straightforwardly fascist, but it is worth remembering, given that we are used to seeing punks and post-punks as leftist. In fact, late 1970s bands in the UK especially, coming from the dispossessed, growingly deindustralised areas, could often, like Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, become reactionary. The new disillusioned, often Tory-voting generation felt they owed nothing to the welfare state or post-war social-democratic reforms, adapted a weird self-made man ideology indebted to Bowie, and associated rebellion with forbidden symbols – at the same time as fascism was reemerging in the UK in the form of large votes for the National Front.

But Bowie’s fascination in totalitarianism extended also to Stalinism. It’s in Eastern Europe that he found a solace and a cure for his mental and health crisis. His interest originated with an idea to adapt Orwell’s 1984 as early as in 1974, which was in turn spurred by a journey from Japan to Moscow on the Trans-Siberian in Spring 1973; he also stopped in Warsaw, years later leaving it a homage of the incredibly solemn ‘Warszawa’, which he later said was supposed to bring a sense of "freedom" to those trapped on the other side. His escape to West Berlin in 1976 brought his attention to the slower-paced everyday reality of men and women in the less affluent East, and staying in Wall-divided melancholic, concrete capital of cold war Europe brought poignancy to his work. This of course heavily influenced his masterpieces, Low and Heroes, which are both in their structure and logic marked by a Germanic rigour and historical gravitas absent from his previous output. Most famously, "Heroes" is a song on a Wall-divided lovers, where Bowie sings of "the shame on the other side" (the GDR snipers, naturally) and threatens to "beat them forever and ever". More importantly, in the solemn if sinister beauty of those two albums, he invented a certain aesthetic blueprint for the whole autodidacts of the post-punk generation, who he pointed towards the bleak reality of the Soviet Bloc, which in their hands became fascinating and glamorous.

Are we then to leave Bowie’s previous disturbing "fascinating fascism" episode behind? Interestingly, in the Summer 1977 issue of International magazine, a publication of the British section of the Fourth International, a certain Carl Gardner fervently defended Bowie against such accusations. "The relationship of politics to art" – he argued – "particularly on one individual artist’s politics, is a far more complex question than a simple equation". To prove it, the author brings the new album Low, where not only the previous concept of charismatic, authoritarian stardom is eschewed – but also, by its modern, electronic sound Low challenges the cliches of trad-rock, of entrenched masculinity and easy gendering. Gardner also praised the non-hierarchical use of instruments, where those two white bourgeois men, Bowie and Eno, were feminist and emancipatory. Bowie’s persona became somehow weak and non-spectacular: "He is integrated into production, not sitting on the top of it". "There’s no way fascism could make use of such tracks as ‘Warszawa’, ‘Subterraneans’, ‘Weeping Wall’" – he concludes, consciously noticing how Bowie’s music has become an intellectual challenge for the listener, not just an automated rock experience.

It’s fascinating that in 1977 a member of the Communist Party of Britain could seriously discuss "progressive" aspects of the avant-garde approach of contemporary music, as if it wasn’t 1977, but 1927 – one could contemplate what has been lost in the meantime. But such reception was I think wholly deserved by Bowie, who on the Berlin Trilogy, including also 1979’s Lodger, actively pursued the new in sound, inspired by electroacoustic music, Kraftwerk and Krautrock bands, such as NEU! and Harmonia, then at the forefront of invention. But Bowie made all this so culturally attractive and alluring that he inspired a whole set of socially and musically progressive, fashionable bands too. Think of The Human League’s odes to industry, Visage’s glam-disco futurism, Ultravox’s namechecking of Hiroshima and cold war Vienna wrapped in metallic, Germanic sound. Or even Depeche Mode experimenting with industrial, concrete sounds and coming to record in the same legendary Hansa Tonstudio in Berlin, and later becoming hugely popular with a younger generation within the Eastern Bloc.

From the late 1970s onwards, Bowie repeatedly disavowed his comments on fascism, and if anything, his work seems strongly anti-racist. The band that made the apparently so Teutonic and ‘European’ Berlin Trilogy was made up of black jazz and funk musicians like George Murray, Dennis Davis and Carlos Alomar, while Bowie had championed black singers and musicians on his "plastic soul" records such as Young Americans. In recent days, a 1983 clip has circulated where Bowie aggressively questions an MTV presenter about its openly segregated approach to musical broadcasting. He remained politically elusive. He repeatedly rejected accepting a knighthood from the Queen. We could speculate whether that was because he despised the empire, but the truth is Bowie would never issue any straightforward political statement of such kind. It just wasn’t his thing. Thanks to that his art functioned on a higher, less direct, but more powerful level, by its complex beauty inviting new generations of listeners to think about the more challenging moments of 20th century history.