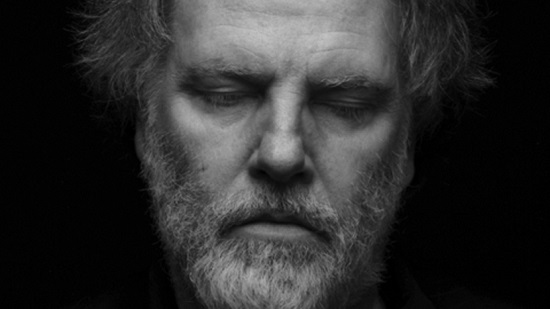

Canadian director Guy Maddin manages to be both cult and current. A jubilant dabbler in all things early cinema, he has championed the old school auteurism of Fritz Lang, Robert Wiene and Busby Berkeley while displaying an utter and obvious delight in the weird and wonderful. His manifesto to forge new ground with the detritus of yesteryear’s cinema greats and mistakes has seen him make countless entertaining shorts and feature films, of which The Forbidden Room is his 11th.

The Forbidden Room plays like a vaudeville revue of all Maddin’s greatest hits. A must for fans of Careful, The Saddest Music in the World, My Winnipeg and Twilight of the Ice Nymphs. It’s full of demonic doubles, amnesiac encounters, temptress skeletons, strange psychoanalysts, duplicity, danger, humour, blood, sex and death. A woodsman vies for entry into a gang of cave-dwelling outlaws by completing a series of tasks at turns Herculean and hilarious. An alluring stranger entraps a talented psychoanalyst to kill her inner child. A moustache lets us in on its memories and more. It all ends in a not-to-be-missed Volcanic crescendo of molten cinema magic.

Co-filmed with director Evan Johnson and co-written with great American Poet John Ashbery, The Forbidden Room was staged in front of live audiences between Montreal and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Maddin’s usual troop of favourite actors came for the ride, alongside cinema greats like Charlotte Rampling and Udo Kier. It’s clear Guy Maddin’s imagination orbits somewhere slightly more off-centre than most filmmakers. Maybe that’s what has drawn one of arthouse cinema’s grande dames, Isabella Rossellini, to the director’s side so many times.

The Quietus sat down with Guy to find out the origins of his cinematic obsession and talk about a career that’s been as strange as his films.

Can you tell me a little more about The Forbidden Room and the forthcoming project Seances and the difference between them?

Guy Maddin: Seances is an internet project where I intended to adapt at least a hundred and maybe three hundred lost films into ten and twenty minute long fragmentary versions. We then uploaded them to an internet archive that fragmented them even more. We treated them like shreds of lost movie spirits and allowed these spirits to interrupt each other in non-consecutive collisions that formed new movies. Part of our program even produces a randomly generated title based on metadata. The first one that came up when we tested the website was Wise Trumpets Of The Milky Midnight. A bunch of spirits of lost films interrupt each other in a way that formed a pleasingly continuous narrative. Pretty dreamy though. Then other parts of the internet started to interrupt. A youtube cat video even came in for a little while, it was very cute then it too was eclipsed by another lost film and then some more stuff from I-don’t-know-what part of the internet and then it ended and the program then destroyed that combination of elements, never to be seen again, and Wise Trumpets Of The Milky Midnight is now a lost film. The website will both produce and lose films – unique one screening only films. So I’m hoping that if someone really enjoys their experience it will conjure a sense of pleasure and a sense of loss in each viewer.

The Forbidden Room and Seances are related. Both of them are made up of lost film matter adapted through the medium of me and Evan, but the way they present themselves is totally different. One of them is this big Russian nesting doll of movie narratives and the other is much shorter experience on the internet.

How was filming in front of live audiences in Montreal and the Center Georges Pompidou in Paris?

GM: Very noisy, lots of people, there were so many people talking that they actually just homogenised their voices into a conch shell sound of the sea. That was very easy to record dialogue over, strangely. It was beautiful. Everything was dreamy and uninhibited and the actors were just interpreting their roles – the only direction I ever gave them was if I ever missed a gesture with my camera. I usually just let them dream perform, considering all these lost movie narratives come from some sort of limbo or afterlife I felt that they would act out their long forgotten plots with a disinhibition.

Where do you draw your inspiration from?

GM: Oh man, I don’t know. I started making movies in my late 20s, that time in an artist’s career that often sees artists just imitating things that he or she loves. I just wanted to be great like L’Age d’Or vintage Buñuel. I wanted to be Busby Berkeley, for crying out loud! I wanted to have chorus girls stomping their heels in my casting office. I wanted to be Erich Von Stroheim monogramming underwear for extras. So I started off my career doing that, and that was fun, but I realised I wasn’t very good at it. But in the act of attempting to imitate I discovered that I had a voice of my own. Whether I liked it or not was another matter. I found that I was my best or that I pleased myself most or came closest to my goals when I was tapped into something autobiographical. I guess what inspires me most is the desire to draw out feelings that feel best expressed on the written page by really good authors, and I’m not a really good author. I feel like my job as a filmmaker is to eff the ineffable, to take feelings that only poets could describe with words and try to project them on the screen for viewers to feel. I don’t think I’ve succeeded once but in the act of trying I’ve come up with all these other results which sometimes intrigue me.

And your obsession with lost films?

GM: I wandered around in a confused daze for most of the ’90s unable to even remember why I wanted to be a filmmaker and somehow I found myself at the turn of the century. I used lost film as an excuse to express myself. The fact that you couldn’t see Alfred Hitchcock’s first film The Mountain Eagle, or that you couldn’t see so many of F.W. Murnau’s masterpieces, or that you couldn’t see so many of Oscar Micheaux’s really intriguing race melodramas, made with fierce independent spirit against all odds in ’20s and ’30s America. That stuff haunted me. They really did bring to life a sense of 20th Century history: cultural history, pop history, gender politics and race politics, socio economic history, all that stuff. It was bracing and instructive.

I just discovered that there were so many lost movies that were all mine to take if I wanted to take them. I was drunk on greed when I encountered this motherlode of utterly fascinating narratives that time’s great river washed up on its banks for me to just scavenge, and not even rub clean, just repurpose and take credit for. It was kind of one of those weird dreams that where you keep finding free money.

So it isn’t just about helping great old films find new audiences?

GM: I learned about half way through my shooting at the Centre Pompidou in Paris that I was not doing it out of a lifelong mission to pay homage to cinema that once was. This lost Three Stooges movie called Hello Pop that we were adapting as an all-female version, it was discovered the day before we went to shoot it in New Zealand and I was furious. I was spitting mad that now we had to give up my Three Stooges adaptation and find some other lost movie at the last second and try and make the props from a Three Stooges movie do for a Kenji Mizoguchi film. I was furious that someone had found this lost treasure. I love the Three Stooges but I refuse to watch Hello Pop. I don’t want to see those guys slap each other in technicolour, it’s their only colour film. I’m sulking still to this day.

I hope all the lost films stay lost.

Lois Weber, she was a contemporary of D.W. Griffith, a really good filmmaker. Where Are My Children? is an unbelievable film, looks gorgeous, years ahead of its time. It looks like Jean Cocteau collaborated with her on a film made around the time of Birth of a Nation. She was really progressive and believed in birth control, suffrage (that hadn’t be won yet for women in America) and eugenics (which calls for the compulsory sterilisation for poor people and criminals). It was considered very progressive at the time because, I guess, selective breeding was a very promising prospect that had a lot of advocates. These would be considered fascist ideas if a couple of decades had gone past and they’re egregious but they’re really fascinating and she’s a wonderful filmmaker. If anyone remembered her she’d be considered a more controversial figure than Leni Refienstahl.

Who you almost worked with?

GM: Yeah that was a close call. She sent me a little letter, a very flirtatious, sorta horny fan letter after seeing my Bergfilme Careful. A mountain film I made without ever having seen a mountain film. I just heard about this genre that was popular in Germany, maybe the German equivalent of the American Western. I figured, what could possibly happen in a mountain film? People climb up? People either climb or fall or jump down? They fall in love. They maybe have a duel, maybe there’s an avalanche. So I included all these elements in a Bergfilme that I made without ever having seen a Bergfilme and sure enough that’s exactly what happens in them. And Leni had seen that and written me a little fan letter, which pleased me. But then we started talking about working together and I’m really glad I had some friends that counselled me that that would be dangerous. She had been flying under the radar for a few years, but then The Wonderful, Horrible Life Of Leni Refienstahl came out and whacked the hornets nest. I was arguing frequently with my girlfriend in those days and she was telling me “You can not work with Leni Refienstahl” and I was going “Oh Yeah? Watch me!” But it was mostly out of stubbornness that I would have completed a working relationship that would have tarred me for the rest of my life. I’ve done my research on Leni and I don’t want anything to do with this person. Just a horrible, horrible person. You know some psychopaths or sociopaths or heartless creeps are at least nice to be with, but she’s socially a bully as well. She would’ve been a monster.

Definitely a bullet dodged.

GM: There are many other bullets I haven’t dodged but I don’t have time to go into that at the moment.

In a way your work is about mistakes or more clearly old ways of expressing film language that sometimes have been phased out, they’re kind of ludic too as well as experimental and celebratory.

GM: Well, I’m more experimental now. Whatever experimental film aromas cloaked my movies were because I’m a gleefully clumsy, primitive filmmaker. I really like traditional pleasingly narrative films, but I also just couldn’t resist throwing in the disruptive. It seems to me that art-house film is at its glorious zenith right now, maybe it can even get better? There’s just so many good films, you know Cemetery Of Splendour, Arabian Nights, Miguel Gomes, just so much great work coming out.

Is that because people feel more free to experiment in film making because its more available and people are more cine-literate than before?

GM: It’s funny how film is the slowest art form to adapt to freedom. It’s had freedom all along. It could’ve done whatever it wanted to. You know the same freedom that do-it-yourself punk and post-punk musicians had in the late 70s and ever since. That’s about the time I started getting interested in film, and I assumed that film would be moving along with the other pop culture forms. Its finally done it but it’s taken decades for it to catch up just to basement band level.

There were bedroom musicians and garage musicians and now there can be bedroom filmmaker and garage filmmakers?

GM: Yeah. When I started making films I just decided “I’m the filmmaking equivalent of a garage band and I’ll just make my garage band movies.” But even the same musicians from garage bands would go to my movies and you could tell what they liked from the way that they dressed and they would be the first ones to walk out. They’d rather go to Star Wars. By the way in France The Forbidden Room opens head-to-head against Star Wars on December 16th. I’m delighted. Bring it on Star Wars. It’s mano-a-mano now. It’ll be blockbuster versus blockbuster in Paris.

You said that you don’t like alienating audiences but you do like playing with them, surprising them and teasing them?

GM: When I sit down to draw with my four and eight year old granddaughters, we understand each other and we make drawings that are really playful and have emotional content but are also flippant. Sometimes they’re just scribbles for their own sake and sometimes they’re very moving and beautiful and seem to have meaning that even their creators don’t quite understand yet. I just respect audiences to understand that that’s what goes on in movies. I just try to make movies that respect the intelligence of the audience. Respect that they understand that the narrator is always unreliable and respect that they understand that the medium can do whatever it wants.

Your films also have a pure emotional content. They’re very present. Full of love and folly, and grief and anger.

GM: I love melodrama. I love the simple fact. When you read Euripides he’s a page turner. It’s like reading a Mexican comic book romance.

They’re entertaining, the language is great, and everything is uninhibited. You know the feelings everyone has and they’re the same feeling you have frequently: jealously, hatred and lust, just reconfigured into timeless family and social dynamics. You recognise yourself but they’re just so beautifully rendered. It’s like watching a John Waters movie or a George Cukor film or a Joseph Von Sternberg movie or a Douglas Sirk movie. These people all belong in the same Olympus as Euripides.

And their dream logic?

I like the way we get to be uninhibited in our dreams, we don’t’ need to repress our behaviours like we do in our daily lives. If we lust after someone in a dream we get to possess him or her, if we dislike someone we get to express it or even strike out at them. Something I wouldn’t think of doing, I don’t have the courage, and it’s not right either. If I feel like crying, I’ll just cry in a dream. Something I really try not to do in my waking hours. I like good melodrama because it’s just an undumping of all these compulsions we feel that we work so hard to master during our waking hours. No wonder we crash to sleep in bed at night. We have to, otherwise we’d just spend our waking hours shredding the feelings from everybody else. Shredded feelings are the fuel that feed the machinery of melodrama. And good melodrama just has honest feelings and is honest about the way people interact.

A lot of your films are personal excavations and you and your experiences feature in them. Is this melodrama therapy too?

GM: It is. I didn’t expect it to be therapy. Sometimes I didn’t want the therapy to work. Whenever you take a subject you’re obsessed with or that haunts you, and make a movie about it, you’re converting it into work units that need to be completed. You gotta turn it into a treatment, a script, a grant application, a bunch of forms to be filled out, a shooting schedule, casting sessions, auditions, shooting, editing, music compositions, the film festival circuit, interviews even. And by the time you’ve finished the process you’re so sick and tired by something that was once very precious to you that you’re done with it. In my movie Keyhole I took something that was very precious to me: the sweet dreams that haunted me every night at my childhood home. I had one shot at reproducing those feelings on screen, I knew it and I think I failed completely. So that was my chance. I don’t care about my childhood home anymore. I’m cured of it.

You excised it by way of film?

GM: Yeah, you also convert real memories, whatever that means, into film versions of those memories. Because by the time you’ve finished the project you can’t remember the real memories anymore, you just remember the film versions of them. And then if the film failed you have distaste for them. So I don’t think about that stuff anymore. I am no longer haunted by my dead father. I am no longer haunted by childhood home. There’s so many things I’ve cured myself of without realising and now when I’m embark on a project I know I’m going to cure myself of it.

I directed Dracula: Pages from a Virgins Diary, a ballet version of Dracula, a few years ago. In order to get into it I had to read the novel and find myself in the novel. I found out that Dracula is created by jealous men. I think he’s just a figment of the imaginations of jealous men and a bunch of horny women. And the jealous men can’t stand Dracula or the horny women so they imagine Dracula to exist. This perfect other, who’s rich, handsome, who’s beyond them, more powerful. So they drive a stake through the hearts of the women, so they can’t love this other. They fill their mouths with garlic so they can’t talk about this other. And they chop their heads off so they can’t think about this other anymore. So Dracula doesn’t even have to exist. I found that take in their because I used to be an insanely jealous young man, and I just realised this novel ingeniously was about me. When I made this ballet, which didn’t seem to be about that, I had to change and re-choreograph it so it could be about me. And then it actually cured me of my jealousy. I was tired of talking about jealousy. I didn’t care about what the object of my obsession talked about, thought about or loved. It was time to move on like an adult in the real world. So therapy, yes!

Maybe we should all make films.

GM: You know there’s something to it, but it’s tiresome and labour intensive. But also just aversion therapy, maybe you should just be forced to watch yourself doing all these horrible things you’re trying to cure yourself of. It’s basically what I’m doing, I’m basically just faced with myself and every day I get up to make movies. I’m pretty sick of myself. I think the ultimate therapy is that I think I’m cured of myself now. I’ve been using the first person singular a lot in this conversation but I don’t know if I can use the word ‘I’ anymore after this sentence I’m just completing. Guy Maddin will have to refer to himself in the third person from now on. He is cured!

Thank you very much, Guy Maddin.

GM: He is pleased to have spoken to you.

I enjoyed speaking to you too.

GM: He thanks you!