Despite the fact that Another Green World was released 45 years ago this autumn (and failed to chart in any locale of That Green World of 1975), it is still one of Brian Eno’s most celebrated and enduringly influential musical works. While rarely stated as a conceptual landmark on the scale of, say, Music For Airports or Discreet Music, or even generally considered as important as the relatively reactionary beginnings of his post-Roxy Music solo career in Here Come The Warm Jets, it’s certainly the shining crown jewel of his pre-Ambient work.

Another Green World stands alone in a discography and legacy that has weaved its way from the twisted rock & roll of its roots (Here Come The Warm Jets), around its preternatural pop sensibility (Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy, Before And After Science), through to conceptual art projects (the Ambient series), film soundtracks (Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks) utilitarian library music (Music for Films I-III, Textures), generative installation pieces (January 07003: Bell Studies For The Clock Of The Long Now, Lux) and back to pop again in recent years (his 2006 collaboration with David Byrne, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today and his further work with Karl Hyde of Underworld). While each of these eras and projects seem to inhabit one idea and explore its permutations to their logical conclusions, it’s as if Another Green World encapsulates every strand of Eno’s work that came before it while simultaneously laying the groundwork for everything that he created afterwards, in one singular vision.

It’s curious, then, given that it would become such a resolved summation of previous efforts and an assured blueprint for future endeavours, that upon arriving in July 1975 at Island Studios in Notting Hill, North West London with trusted producer and engineer Rhett Davies, Eno had absolutely no idea where to begin. As he would later confess to NME’s Barry Miles: ‘The first three or four days I didn’t get anything done and I was really frightened. I think I started about thirty-five pieces and some of ‘em were real clutching at straws in real desperation.’ However, with the aid of the Oblique Strategy cards that Eno had developed with fellow artist Peter Schmidt now existing in a commercially available format – cards with short aphorisms printed on them intended to encourage lateral thinking and designed to help artists out of creative blocks – he turned to the cards as an impetus for spontaneous studio recordings, at times using a cast of other musicians to which he gave similarly short and interpretable instructions to. As a means for exploring some of the many facets of this groundbreaking album I have chosen from my own set of Oblique Strategies at random to help guide us through the background and the personal resonance of a record that remains a fascinating snapshot of one of pop music’s most innovative curators.

Listen to the quiet voice

Something that sets Another Green World apart from other albums of its time, and indeed the 45 years following it, is its reckless zigzagging of mood, feel and genre. When the sessions finally kicked into gear, it appears that Eno felt unashamed to follow his creative muse wherever it might take him and he ended up with a mesh of influences that surround the album, from art pop, minimalism, jazz, folk to German kosmische musik and many other strands between, all adding to his tapestry of inspiration.

One defining aspect of how Another Green World works as an album is the ratio of instrumental and vocal tracks that were skewed in favour of the former, there being only five tracks featuring vocals on the album. This constant shifting of the foreground would become a sequencing choice that Eno followed to some degree on 1977’s Before And After Science, as well as probably influencing the first vs. second half sequencing of the first two albums in Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy, Low and “Heroes” of which Eno quite famously contributed to (and were, amazingly, both released in the same year as Before And After Science). Yet Another Green World’s structure remains very different to other albums in Eno’s canon. It wasn’t just that you could go for two or three songs without hearing his voice interrupt the mix once; it was that the instrumental tracks between were not merely interludes or fragments but very realised and resolute pieces in themselves, even if their length suggested they were closer to transitional vignettes than what they operated as.

Eno conveys strong emotions or evocative landscapes in under three minutes quite consistently. The best example being the title track, a relaxed lilt of a melody that drifts into frame, bobs there for about sixty seconds and then slow-fades off into the endless horizon of a world where that piece of music would ideally loop in comfortable infinitum. Perhaps I conflate it in my mind too heavily with where it was used to brilliant effect on the opening sequence for the BBC’s Arena arts series, in which a bottle with the word ‘Arena’ inside it, lit in neon, literally floats on water through a mist and into view. Regardless, the capacity to paint visual landscapes with instrumental music would eventually become Eno’s modus operandi and on Another Green World we are experiencing it in a way that was unlike any other he would explore again.

Where’s the edge? Where does the frame start?

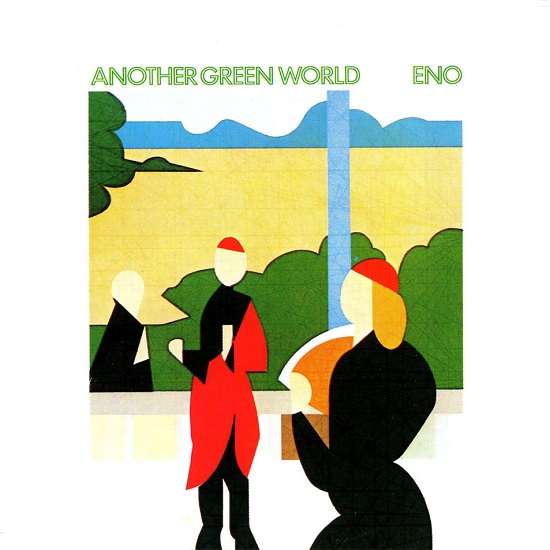

The front cover for Another Green World is a detail from a painting entitled ‘After Raphael’ (1973) by Tom Phillips, one of Eno’s mentors and friends from his Camberwell School Of Art days. Further research on the original piece will show how dramatic the crop of the artwork is that ended up on the final album sleeve, much of the focus of this renaissance-referencing, geometrically precise painting being shifted to a scene in the middle-right whereby three regally postured figures are proportionately spaced between each other, one presumably outside the window conversing with another one inside while the third looks on, fanning itself. Aside from noticing that these three figures going right-to-left chronicle what I believe to be the devolution of Eno’s hair from art school to present day in three easy stages, the simplicity of the colours and shapes could also hint at Eno’s beloved Mondrian, the paintings of whom he saw as a young boy that helped spark his initial – and very much sustained – interest in visual art.

The crop here also presents a potentially interesting conceptual parallel with how Eno would use the material recorded by his guest musicians under his instruction, to create loops that were then ‘treated’ to imagine new sonic worlds and influence unique song structures. Phil Collins, who played drums and percussion on several of the album’s cuts, alongside his Brand X band mate Percy Jones on bass guitar, would run through their dictionary jazz licks together and Eno would record them and make a loop of them, thus framing the talents and contributions of others and creating something new from them. This method perhaps best conveyed in the brief instrumental jazz number ‘Over Fire Island’, where at one point the drum track is duplicated and the clone is panned left, shifted back in time by a quaver but kept in perfect tempo sync, creating a natural tape delay effect. The very different scenarios and environments created by Tom Phillips’ original painting and the severely cropped version that ended up on the cover point at Eno’s ability to use pre-existing ideas and make them his own through editing and treatment.

Use ‘unqualified’ people

While the sentiment of this particular Oblique Strategy may well justify Eno’s decades-long reassurance that he is a ‘non-musician’ who is apparently fairly capable of producing astoundingly sophisticated musical results, it arrives here in the form of a blatant contradiction. While the pool of musicians used on Another Green World may be relatively small it does, however, include Phil Collins of Genesis, Percy Jones of Soft Machine, Robert Fripp of King Crimson, Paul Rudolph of The Pink Fairies and John Cale of The Velvet Underground (and his own fruitful solo career up to this point). Not to mention producer Rhett Davies keeping the sessions that initially started in failure tidy and organised enough to allow Eno more room to improvise and impose his systematic approach to new recordings.

John Cale’s input here is particularly noteworthy, his multi-tracked viola dissonance on the powerful opening gambit of ‘Sky Saw’ recalls the eerie drones of ‘Venus In Furs’ from the first Velvet Underground album that was a huge influence on Eno’s future propensity for balancing avant-garde art with pop music. If anything, in the landscape of the mid 1970s British progressive rock and pop art music scene, we have here some credentials of immense superiority. It’s also worth considering, however, that half of the tracks on Another Green World were performed and composed entirely by Eno himself. Not that this should be a surprising fact in itself, but that the immaculate consistency of the album doesn’t dip due to Eno’s own admittedly rudimentary skills of playing any instrument, contrasting with the sheer pedigree of his contracted musical collaborators, lends credence to just how strong Eno’s ideas (and their influence over the organisation of other musicians and his own treatments) could be.

Distorting time

One of the more crucial collaborations on Another Green World is the guitar proficiency of Robert Fripp. While Eno and Fripp had already released their technologically innovative, heavily droning and meditative album (No Pussyfooting) two years previous to this, and would in the same year as Another Green World release their second recorded collaboration Evening Star, Fripp’s contribution to Eno’s shorter, more pop-leaning song works would provide a few of the album’s most densely aural highlights. Take, for instance, the blistering rapidity of the guitar solo on ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ in which Eno instructed Fripp to imitate the electrical charge of a Wimshurst influence machine – an electrostatic generator that generates high voltages through the contra-rotation of two large discs, creating friction between them and two crossed bars with metallic brushes, and a spark gap formed by two metal spheres. The resulting solo is quite possibly the most inspired improvisation that Fripp would end up committing to tape in his entire career; his smooth, compressed fuzz of a guitar tone instantly recognizable from the moment the fader is raised to introduce him.

As Eno said to Paul Morley for The Observer back in 2010: ‘Instruments sound interesting not because of their sound, but because of the relationship a player has with them.’ Never truer, it seems, than for Robert Fripp, who can play merely two notes and you are suddenly very aware who the person skilfully wielding the axe is.

Do the words need changing?

It must be pointed out how dense and varied the myriad sounds on this album are and how their minutiae adds to the development of a constantly changing and ever-welcoming world of immersion. Take a glance at the credits for the album and littered throughout it are creative descriptions of Eno’s treated instrumentation; ‘Anchor Bass’, ‘Choppy Organs’, ‘Spasmodic Percussion’, and my favourite: ‘Uncertain Piano’. The guitars themselves are affixed with words like ‘snake’, ‘desert’ and ‘castanet’. The music on Another Green World is incredibly evocative of many things, but it’s also quite difficult to write about it descriptively when it’s as if Eno has done most of the work for you already. While there’s something that I find deeply naff about giving the instrumental sounds their own names, at the same time it adds a charm to the treatments. It creates at least some sort of humorous distance between the concept and engineering with the resulting sound. This stylisation is one that Eno had established two albums earlier and it would be one that he would continue to the present day.

Retrace your steps

Just as the listener may feel they are getting a hold on the rapidly changing moods and aims of the album, Eno confidently strides in with the unabashed pop of ‘I’ll Come Running’, which serves as Another Green World’s centrepiece. The effect is at first jarring, but not long into the track it all starts to make sense. Even though the feel is wildly different from what comes before it, the elements are sonically in keeping with the overall world that the album is trying to establish. As David Sheppard puts it in his excellent authorised Eno biography On Some Faraway Beach: The Life And Times of Brian Eno: “‘I’ll Come Running’ was a case of reshuffling instruments and sounds already familiar from the five preceding tracks, and laying them out, for once, in comparatively conventional order.” Even through the advanced sonic experimentation and systems-based approach to composition, Eno’s penchant for flawless pop melody and indeed his ability to perform it convincingly has been something that has freed both his solo work and his capacity as a producer for other bands from the cold theoretical contexts it could so easily become shackled by.

‘I’ll Come Running’ originally debuted in a primitive form as the song ‘Totaled’ on a John Peel session in 1974 with Eno’s then backing band The Winkies. The Winkies’ fast-paced rock & roll dynamism coupled with Eno singing the melody an octave higher than when it would appear on Another Green World, transported it more into the musical territory of Here Come The Warm Jets, which, in 1974 Eno and The Winkies would have been touring in support of. The more restrained pace and the recalling, in parts, of the sort of 1950s doo-wop music that Eno devoured as a young boy in Woodbridge, Suffolk, make up the eventual rendition of ‘I’ll Come Running’ into as devotional and as sentimental of a love song that Eno has ever written. It provides an accessible and poignant emotional mid-point and in doing so strengthens the musical perambulations that surround it.

Would anybody want it?

It’s somewhat depressing to learn that on both sides of the Atlantic, Another Green World failed to chart, though it did reach number 24 in New Zealand in 1979, presumably off the back of one of Eno’s other collaborations during that time. However, the capacity for albums of groundbreaking artistic importance to be both critically and commercially successful was even by 1975 becoming a well-established musical unlikelihood. Critically, it fared well at the time, as Charley Walters of Rolling Stone in 1976 would call it "perhaps the artist’s most successful record" and admitting that, "I usually shudder at such a description but Another Green World is indeed an important record and also a brilliant one." But it has been its enduring and increased reverence over the years that have kept the album from becoming marginal in Eno’s discography. Take for example Biba Kopf in The Wire, June 1992: "Britain’s ambient and electronic pop cottage industries are inconceivable without Another Green World. Pity other practitioners didn’t listen more closely." Or Will Hodgkinson giving it five stars for Mojo back in 2009: "Eno managed to reconcile his opposing character traits of trickster and mega-brain perfectly in this reflective classic." Chris Ott in Pitchfork reviewing the 2004 digital remasters of Eno’s first three solo albums would give Another Green World 9.8 out of 10, and of course there is the publication of Geeta Dayal’s 33 1/3 book from 2010, the inclusion in the series of which generally substantiates an album’s consensual and continued relevance.

Reviews aside, however, the bizarre coincidence that two generally popular yet very different independent films released this summer, namely Me And Earl And The Dying Girl and The End Of The Tour both featured ‘The Big Ship’ – perhaps the most hair-raisingly emotional instrumental cut on the album – in their climactic closing sequences is a further indicator of the potentially endless relevance of this album. Greg Cwik writes in The AV Club of this curious pop culture micro-phenomenon in much better analytical detail relating to the films. It bears mentioning though, that when I saw The End Of The Tour at this October’s London Film Festival, the moment I heard the reverse-reverb fade in of the introductory C-major chord, it wrapped itself so perfectly over the contours of that particular scene of James Ponsoldt’s David Foster Wallace biopic that my heart strings were duly snapped at their tension points and I fought back the tears only because I wanted to savour the intense friction of feeling a delayed realisation and such a severe near-release of bittersweet emotion, at once for the musical choice at hand, again for how well it worked, and once more for what was occurring on screen. Perhaps we are now only really re-imaginging Another Green World to fit our modern day concerns where it seems it was disappointingly ignored at the time of its release.

Remember those quiet evenings

My personal attachment to this album, though, goes deeper than its huge artistic influence on my work as a musician. Another Green World for me is inextricably rooted in times of quiet isolation and contemplative solace in the subtopian landscapes of Chandler’s Ford, Hampshire when I was between the ages of 16 and 18. This was, admittedly, around the time I should probably have been getting high in parks at night with my friends and indulging in excessive drinking. I don’t consider myself above that kind of behaviour, though I probably did to an extent at the time, and maybe part of me regrets my self-imposed solitude, but really I felt invigorated by and found meaning in other things that provided more transcendence from my suburban surroundings than any quantity of bad alcohol could, and they were usually things that I did alone. I would ride my bike daringly through listless exurban avenues, to the extremes of cul-de-sacs, over the more dramatic terrain of nearby woodlands, parks and copses, and Another Green World would often be blaring in my ears while I did this. My relationship with my immediate environment, both suburban and pastoral, was soundtracked so heavily by it that I couldn’t escape it crowbarring an influence into the creative existence that was just starting to bloom on my bedroom computer recordings. These were such vital journeys and experiences for me. I saw St. Elmo’s fire splitting ions in the ether.

I would often listen to albums on my walk to college and Another Green World’s 40 minutes and 48 seconds almost always lasted the entire duration door-to-door. Through those sometimes dread-laden, at other times energised walks into my place of higher education I would experience the changing of seasons through the melancholy filter of ‘Golden Hours’, I would become sullied in the rain to the reflective ‘Zawinul / Lava’. On one occasion walking through Fleming Park, the synthesised wind noises that open ‘Becalmed’ blended seamlessly into the sound of powerful gales pushing against me and suddenly the idea of the environment acting as an external instrument became a very visceral and exciting one. Eventually during this period, the golf course that attached itself on to Fleming Park was shut down and you were free to wander through the fairly well tended grounds there at your leisure, now without the fear of being clobbered by a ball. Alongside the park was a row of pylons that stretched out adjacent to an overpass, and the motorway that reached towards London, or back in on itself to nearby Southampton, roared beneath these metal structures. The incline of a small hill in the ex-golf course offered a spot for an elevated view out over the motorway and the pylons paralleling it, stretching out into the sleepy suburban distance. Another Green World is firmly ingrained in me in a strong psychogeographical sense. In the cool August moon. These may not have been the environments that Eno intended to conjure or compliment but laying there on the hill looking out into the distance, the pylons jutting out above the cars, the houses reaching out for miles and the sun setting slowly in evening pink, the accompanying soundtrack helped me to consider my place in it all, made the days creak by easier in fresh rotation, made me feel not less alone but more comfortable in my singularity. Everything merges with the night.

It comforts me to learn, when re-watching for the hundredth time or so, the 2010 BBC Arena documentary on Brian Eno, which is fittingly entitled Another Green World, that Eno also fondly remembers similar times from his childhood where he would go off to places on the east coast of England and collect fossils by himself. "I didn’t know anyone else who liked doing that so it was something that I did on my own," explains Eno, "I would just take some sandwiches with me and spend the day looking at stones, really. And I remember that very clearly as being a very happy and transcendent time. It’s beyond thinking, actually." Eno then elaborates on this point, and in doing so I feel he sums up the aims and effects that Another Green World has over the listener perfectly. "I love discovering a place where I feel that nobody’s been before. I love that. A piece of music becomes real for me when it seems to become a place where I can sort of feel what the temperature would be, and what the light that would go with it would be, and what colours. I just started making music, deliberately, to create a more desirable reality."

Go outside. Shut the door