On December 7th 1974, BBC Two screened A Passion For Churches, a 49 minute documentary by John Betjeman on the work of the diocese of Norfolk. Even four decades ago Betjeman’s bumbling poetic captured a world that was fast disappearing, congregations of tough old dears with stiff shoulders and a scattering of awkward teenagers in flares. One of the featured churches was Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the village of Knapton, where beautiful carved angels dating from 1504 keep watch over the cold and empty nave. I spent many holidays as a child looking over this church from the windows of a small cottage across the narrow lane that formed the boundary of its graveyard. It sat adjacent to another religious building, a Primitive Methodist Chapel that didn’t have carved angels or indeed much at all in the way of decor. On Sunday mornings organ and hymns would vibrate through the walls. Earlier this year, I visited Norfolk for the first time in years, and happened upon the chapel’s 125th anniversary service, led by a Korean minister, the Revd. Seung Wook Jung. Aside from one young lad sat at the back playing a game on his iPad there weren’t many children there. The hymns were played on CD backing track and at a lunch afterwards, £277.50 was raised for the Nepal earthquake fund.

There won’t be a 126th anniversary for Knapton Primitive Methodist chapel. Earlier this year it was announced that it is to close, with a final service taking place on January 10th 2016. Shortly after hearing this news, I read a fascinating, depressing piece by Nick Davies in The Guardian on the River Ouse in Sussex. In the article, Davies walked with septuagenerian river keeper Jim Smith, the last of his line, who after 52 years working with it rushing around his ankles, knew the River Ouse better than anyone. Now, he’s terrified for its future as extraction further upstream and a general lowering of the water table has started to dry it out. There was nothing he could do about it, for business and people higher up the chain in headquarters decreed it must be so.

The likes of Jim Smith, or vicars and publicans or the other quiet and uncelebrated people who tie their communities together, are a dying breed. Without these unfashionable guardians, how are we to feel our connectivity with wider communities or environments, or understand that we’re not isolated creatures living in boxes that glow with HD televisions, dominating living rooms and mounted in pride of place above the fireplace, but meshed in far wider ecosystems, whether cultural, social or environmental?

If 2015 has seen so many of these uncelebrated people increasingly marginalised, there’s also been the continued destruction of the small, insignificant public spaces in which we once would have met them, and each other. This past weekend London’s Stockpot, a cheap place where many could afford to eat out somewhere that felt like a proper restaurant closed its doors. It was one of the last rough and ready eateries still remaining in an increasingly chi-chi Soho. In another of our Quietus Wreath Lectures Ed Gillett will explore the continued destruction of UK music venues and their replacement by the gaseous bullshit of pop-up lifestyle experiences. 2015 has also witnessed pubs disappearing at the rate of 29 a week as working men’s and social clubs also continue to fail. In our larger cities, community boozers are frequently knocked about, plaster stripped off for a distressed authenticity, and re-targeted at an affluent monoculture. Our town centres have suffered too, with small shops vanishing at an even faster speed than 2014, leaving windows empty aside from dust and a few mournful items even the debt collectors couldn’t be bothered to take. In Epping Forest, the Corporation Of London tried to put one of the famous corrugated iron tea huts popular with bikers out to private tender. It was only saved for the family who’ve run it for decades it after a vigorous public campaign.

Don’t, please, take this talk of Betjeman, chapel and restaurants selling fried liver as conservatism. I also lament, for example, the forbidding and destruction of most of the places where secret and illicit things went on, the late-night drinking establishments, the queer spaces like The Joiners Arms (closed in January 2015) or the smart Bloomsbury squares where you might find an orgy going on under a London plane tree. Kaos, one of London’s finest techno nights, began at Madame JoJos (closed this year) then went to Public Life (now closed) and a warehouse (closed) before arriving at Stunners, a saucy "crepuscular underworld" in east London. When that too was ‘cleaned up’ (closed), Kaos moved to Electrowerks in Islington, a venue now <a href="http://www.timeout.com/london/blog/electrowerkz-becomes-the-latest-london-venue-under-threat-111615‘ target="out">under threat from the planned Crossrail Two.

Society has always been in flux and this is certainly not a nostalgic plea for a golden age of Albion, but 2015 has been a year in which these dramatic changes to our country, and especially London, have seemed to accelerate. As small, unfashionable institutions, practices and people are gradually wiped out, what replaces them is all-too-frequently uniformly, unbendingly corporate. Even worse, it’s often what was once leftfield co-opted by the mainstream. You don’t have to be a patriot or a nationalist to lament that, in 2015, our town centres and mainstream cultural life have continued to become merged into a beige margarine, often Made In America. Visit an English town and take a photo of any high street up to first storey level and it’s nigh-on impossible to tell exactly where you are. This is not the case in the rest of Europe.

It doesn’t take long to acquire planning permission to evict, demolish, and erect steel framed buildings full of luxury flats or fancy offices, with a ‘public square’ or swimming pool offered as a sop to the local planning authorities. A new building for Camden Council, for instance, has been built in partnership with property developers King’s Cross Central Limited. Earlier this year a public swimming pool opened in the basement, a pokey place with low ceilings over the water and narrow lanes, and changing rooms where the hair driers are already broken. It’s a far cry from the smart public pools of the Victorian era, or even those of the 60s. These developments, springing up all over London and elsewhere, might be surrounded by an Iconic Plaza but, as Bradley L Garrett explored in this brilliant 2015 article on the privatisation of public space, who is it for? What point a street food market with a six quid artisanal lunch if you’re merely eating on borrowed ground?

The same goes for the increasing privatisation of spaces within our public institutions. Whereas once they had little cafés staffed by old dears, our hospitals now franchise out their public-facing catering to private companies, with the bizarre result that many now host outlets like Burger King, Costa Coffee, Starbucks and pizza restaurants that put people’s health at risk in the first place. Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England, told MPs in March that "The NHS is being pennywise but pound-foolish selling junk food that ultimately just lands more people in hospital with expensive, preventable, obesity-driven illnesses." It’s a similar insidious corporatism to the Royal British Legion taking money from weapons manufacturers for its annual poppy events. As I wrote in a Black Sky Thinking in November, would veterans of the World Wars have stood for this?

The Tory election victory in May 2015 of course looms large over all this. New Labour’s endless compromises and lack of ambition acted as a softening up campaign that made much of the above possible. This gradual crumbling into tedium began under their watch, and by the time the shock and awe of George Osbourne’s cuts struck there was barely any means of resistance. This is in part why we’ve ended up with Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party. In many ways he’s exactly the sort of awkward, out of time character I am praising here. I voted for him, as a gamble and in hope that he might live up to his promise for a new politics and inclusive party, largely because the other three candidates were a tedious continuation of the blandness of what had gone before. I’ve watched what has happened since with a permanent wince, but despite his ineptitude remain unconvinced that I made the wrong decision.

But if he fails, where as can we look? The small institutions, public figures and spaces that I lament might all seem insignificant but, collectively, used to and still could make a difference, despite capital’s determined attempts to neuter their efficacy via co-option and divide and rule. I’ve often felt elements of the atheist left wing ought to tone down their strident hectoring and remember that social justice is at the heart of many Christian movements, especially Methodism. Similarly, many Christians should consider that Jesus told them to care for the poor, not peer judgementally into people’s bedrooms.

Solidarity can surprise, and happen across divides. 2015 marked the 30th anniversary of the Miners Strike, when the Lesbians & Gays Support The Miners group raised money and awareness for strikers. The NUM subsequently played a major part in introducing gay equality legislation at the core of Labour Party policy, and have traditionally marched alongside their gay comrades at London Pride. This year, LGSM were asked to lead the Pride parade but only if they weren’t accompanied at the front by their Union friends. This prompted an angry plea for Pride bosses not to forget the movement’s radical roots in favour of its corporate sponsors.

Some might argue that resistance and solidarity is now best explored not in the old-fashioned spaces that I describe, but online. To an extent I agree – the incredibly swift turnaround on societal awareness of trans issues has been largely driven by the internet. An old school friend has recently transitioned, and is receiving excellent support in her workplace and church. I’m not sure this would have happened five or ten years ago.

I am concerned, though, that we’re not building communities on social media but raging, mirrored snakepits. Hectoring call-out culture and the complete lack of nuance when shouting in 140 characters at someone you’ve never met is hardly a replacement for a face-to-face discussion, much as you might have once had in café, pub, community centre or church. Social media also gives the illusion of community and solidarity. Even if you’re not slamming someone who ought actually be an ally, just how broad can your reach be? As Helen Lewis of the New Statesman wrote in July, "The echo chamber of social media is luring the left into cosy delusion and dangerous insularity". For solidarity to be effective, indeed, for it even to exist, it has to be cross-generational. Worryingly, there’s a vast gulf opening up between those who spend much of their lives online and fully immersed in social media and the latest in fast-moving cultural mores, and those who don’t.

Many of the themes explored in this opening Wreath Lecture will recur in those to follow over the coming weeks. It’s not that I am necessarily entirely pessimistic about the future, rather concerned that writing off certain spaces, people and ideas as outdated, irrelevant – even problematic – risks removing them both as instruments of social cohesion and as an awkward roughness that might slow our slide into corporatist cultural myopia. There are places that are still sticking in the mud, of course, and building new networks. Aside from political organisations like Sisters Uncut, it doesn’t take long to find plenty of examples in music – indeed, in some ways I see The Quietus as something of an awkward cockroach, scuttling around everyone else’s fancy trainers, refusing to die. There’s the If Wet organisation who put on great events in village halls and of course Golden Cabinet up in Shipley. It was heartening to see Ramsgate Music Hall, a venue off the beaten track but serving a local community and booking far more adventurous programmes than you might find in many major towns, winning a major award last week. Even in London, the non-profit New River Studios is putting on excellent events and last week I was pleased to be part of the William Morris-inspired More News From Nowhere, a new night of experimental music in Walthamstow that takes place upstairs in an knackered old gay boozer. One of the regulars came up to one of the organisers and I and said "I’m old and this music reminds me of 1990, when we had the good MDMA". I hope these places, another others not connected to music, might be places of new focus where alternative narratives can thrive.

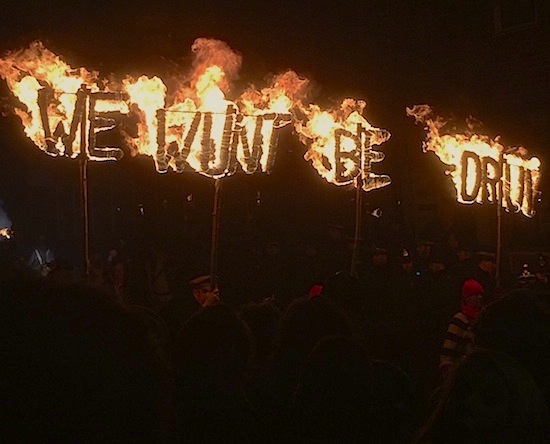

Earlier this year I made my annual pilgrimage down to the march of the bonfire societies and fireworks at Lewes and, en route, was disappointed that the effigy of Cameron on the pig had become denigrated to a LOL and a meme online after a photo of it leaked. Lewes has always seemed to me to be more important than that. It’s a relic of an obstinate, strange, old England where the motto, carried in flaming torches, is "WE WUNT BE DRUV" and local communities unite to throw explosives around their town as the police look on powerlessly. This year with brain glowing I stood on the damp grass around the Cliffe bonfire and watched as giant effigies of Guy Fawkes and Sepp Blatter exploded in the drizzle. Smoke billowed over the railway line from Lewes to Newhaven and, as a train passed along it, in my mind’s (third) eye I saw a vision of the late Nick Sanderson of Earl Brutus singing and laughing in a t-shirt that glittered with the old British Rail logo as he drove the train through a galaxy of sparks. Later, two burly men in striped sailor’s shirts stood exploding huge coils of Chinese bangers in the middle of the street. It was only when they were good and ready, the tarmac carpeted with smouldering red paper, that the police were permitted to drive through, and take back control of the town.